Snapshots from Grotta D'oriente (NW Sicily)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Marine Snails of the Genus Phorcus: Biology and Ecology of Sentinel Species for Human Impacts on the Rocky Shores

DOI: 10.5772/intechopen.71614 Provisional chapter Chapter 7 Marine Snails of the Genus Phorcus: Biology and MarineEcology Snails of Sentinel of the Species Genus Phorcusfor Human: Biology Impacts and on the EcologyRocky Shores of Sentinel Species for Human Impacts on the Rocky Shores Ricardo Sousa, João Delgado, José A. González, Mafalda Freitas and Paulo Henriques Ricardo Sousa, João Delgado, José A. González, MafaldaAdditional information Freitas and is available Paulo at Henriques the end of the chapter Additional information is available at the end of the chapter http://dx.doi.org/10.5772/intechopen.71614 Abstract In this review article, the authors explore a broad spectrum of subjects associated to marine snails of the genus Phorcus Risso, 1826, namely, distribution, habitat, behaviour and life history traits, and the consequences of anthropological impacts, such as fisheries, pollution, and climate changes, on these species. This work focuses on discussing the ecological importance of these sentinel species and their interactions in the rocky shores as well as the anthropogenic impacts to which they are subjected. One of the main anthro- pogenic stresses that affect Phorcus species is fisheries. Topshell harvesting is recognized as occurring since prehistoric times and has evolved through time from a subsistence to commercial exploitation level. However, there is a gap of information concerning these species that hinders stock assessment and management required for sustainable exploi- tation. Additionally, these keystone species are useful tools in assessing coastal habitat quality, due to their eco-biological features. Contamination of these species with heavy metals carries serious risk for animal and human health due to their potential of biomag- nification in the food chain. -

DNA Barcoding of Marine Mollusks Associated with Corallina Officinalis

diversity Article DNA Barcoding of Marine Mollusks Associated with Corallina officinalis Turfs in Southern Istria (Adriatic Sea) Moira Burši´c 1, Ljiljana Iveša 2 , Andrej Jaklin 2, Milvana Arko Pijevac 3, Mladen Kuˇcini´c 4, Mauro Štifani´c 1, Lucija Neal 5 and Branka Bruvo Madari´c¯ 6,* 1 Faculty of Natural Sciences, Juraj Dobrila University of Pula, Zagrebaˇcka30, 52100 Pula, Croatia; [email protected] (M.B.); [email protected] (M.Š.) 2 Center for Marine Research, Ruder¯ Boškovi´cInstitute, G. Paliage 5, 52210 Rovinj, Croatia; [email protected] (L.I.); [email protected] (A.J.) 3 Natural History Museum Rijeka, Lorenzov Prolaz 1, 51000 Rijeka, Croatia; [email protected] 4 Department of Biology, Faculty of Science, University of Zagreb, Rooseveltov trg 6, 10000 Zagreb, Croatia; [email protected] 5 Kaplan International College, Moulsecoomb Campus, University of Brighton, Watts Building, Lewes Rd., Brighton BN2 4GJ, UK; [email protected] 6 Molecular Biology Division, Ruder¯ Boškovi´cInstitute, Bijeniˇcka54, 10000 Zagreb, Croatia * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: Presence of mollusk assemblages was studied within red coralligenous algae Corallina officinalis L. along the southern Istrian coast. C. officinalis turfs can be considered a biodiversity reservoir, as they shelter numerous invertebrate species. The aim of this study was to identify mollusk species within these settlements using DNA barcoding as a method for detailed identification of mollusks. Nine locations and 18 localities with algal coverage range above 90% were chosen at four research areas. From 54 collected samples of C. officinalis turfs, a total of 46 mollusk species were Citation: Burši´c,M.; Iveša, L.; Jaklin, identified. -

Holocene Climate Change in the Subtropical Eastern North Atlantic

Holocene Climate Change in the Subtropical Eastern North Atlantic: Integrating High-resolution Sclerochronology and Shell Midden Archaeology in the Canary Islands, Spain A dissertation submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in the Department of Geology of the College of Arts and Sciences by Wesley George Parker B.A., Geological Sciences, Ohio University, 2015 B.A., Global Studies – Latin America, Ohio University, 2015 Dissertation Committee Dr. Yurena Yanes, Chair Dr. Aaron Diefendorf Dr. Henry Spitz Dr. Donna Surge Dr. Amy Townsend-Small Dissertation Abstract High-resolution paleoclimate data are necessary to investigate climate mechanisms that operate at seasonal scale, like the North Atlantic Oscillation (NAO). The oxygen isotope (δ18O) composition of mollusk shells are a powerful paleoclimate proxy that records the highest (submonthly) resolution because: (1) shells are abundant and often well preserved in the geological and archeological record, (2) many shells grow almost continuously year-round, and 18 (3) the δ Oshell values of many mollusks record sea surface temperature (SST). The application of δ18O paleothermometry in new species and localities requires calibration studies to ensure that selected taxa reliably record SSTs. Additionally, anthropogenic and diagenetic alteration must be assessed to ensure the proper acquisition of paleotemperature data. Shells middens of the Canary Islands, located in the subtropical eastern Atlantic Ocean, provide a unique opportunity to generate novel high-resolution paleoclimate data over the last two millennia useful to assess variations in the NAO and its influence on coastal ecosystems and civilizations. Here I present four research projects that address the calibration and application of δ18O paleothermometry using two species of intertidal gastropods, Patella candei and Phorcus atratus. -

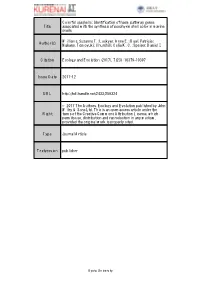

Identification of Haem Pathway Genes Associated with the Synthesis of Porphyrin Shell Color in Marine Snails

Colorful seashells: Identification of haem pathway genes Title associated with the synthesis of porphyrin shell color in marine snails Williams, Suzanne T.; Lockyer, Anne E.; Dyal, Patricia; Author(s) Nakano, Tomoyuki; Churchill, Celia K. C.; Speiser, Daniel I. Citation Ecology and Evolution (2017), 7(23): 10379-10397 Issue Date 2017-12 URL http://hdl.handle.net/2433/259324 © 2017 The Authors. Ecology and Evolution published by John Wiley & Sons Ltd. This is an open access article under the Right terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits use, distribution and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Type Journal Article Textversion publisher Kyoto University Received: 4 August 2017 | Revised: 19 September 2017 | Accepted: 20 September 2017 DOI: 10.1002/ece3.3552 ORIGINAL RESEARCH Colorful seashells: Identification of haem pathway genes associated with the synthesis of porphyrin shell color in marine snails Suzanne T. Williams1 | Anne E. Lockyer2 | Patricia Dyal3 | Tomoyuki Nakano4 | Celia K. C. Churchill5 | Daniel I. Speiser6 1Department of Life Sciences, Natural History Museum, London, UK Abstract 2Institute of Environment, Health and Very little is known about the evolution of molluskan shell pigments, although Societies, Brunel University London, Uxbridge, Mollusca is a highly diverse, species rich, and ecologically important group of animals UK comprised of many brightly colored taxa. The marine snail genus Clanculus was cho- 3Core Research Laboratories, Natural History Museum, -

Republique Algerienne Democratique Et Populaire Ministere De L’Enseignement Superieur Et De La Recherche Scientifique

REPUBLIQUE ALGERIENNE DEMOCRATIQUE ET POPULAIRE MINISTERE DE L’ENSEIGNEMENT SUPERIEUR ET DE LA RECHERCHE SCIENTIFIQUE UNIVERSITE D’ORAN FACULTE DES SCIENCES DEPARTEMENT DE BIOLOGIE Laboratoire Réseau de Surveillance Environnementale THESE Présentée par : BELHAOUARI Benkhedda En vue de l’obtention du diplôme de : DOCTORAT Spécialité : SCIENCES DE L’ENVIRONNEMENT Etude écotoxicologique chez un Gastéropode marin, Osilinus turbinatus (Born, 1780) dans le littoral algérien occidental. Commission du jury composée de : PRESIDENT : O. KHEROUA Professeur, Université d’Oran DIRECTEUR DE THESE : Z. BOUTIBA Professeur, Université d’Oran EXAMINATEUR : A.E.K. AOUES Professeur, Université d’Oran EXAMINATEUR : M. HADJEL Professeur, Mohamed Boudiaf Oran EXAMINATEUR : A. KERFOUF Maître de conférences A, Université de Sidi Bel Abbes EXAMINATEUR : K. MEZALI Maître de conférences A, Université de Mostaganem Année académique 2011/2012 REMERCIMENTS La personne à qui je dois le plus est mon Directeur de thèse Monsieur le Professeur Z.BOUTIBA, Responsable du Laboratoire Réseau de Surveillance Environnementale (LRSE), Université d’Oran. Je le remercie pour l’intérêt porté à mon travail, pour son excellente pédagogie et pour sa confiance qui m’a permis d’acquérir l’autonomie nécessaire pour arriver à ce stade. Je le remercie pour ses qualités humaines plus que toute autre chose. Je lui dois presque tout sur le plan scientifique et beaucoup sur le plan humain. C’est un grand honneur que me fait le Professeur O. KHEROUA Directeur du Laboratoire de Physiologie et Sécurité Alimentaire, Université d’Oran en acceptant la présidence du jury. Je le remercie vivement. Je suis très reconnaissant envers le Professeur A.E.K. AOUES Directeur du Laboratoire de Biotoxicologie Expérimentale, de Biodépollution et de Phytoremédiation d’avoir accepté de nous honorer par sa participation au jury de cette thèse. -

Who Played a Key Role During the Development of Our Modern-Day Taxonomy and How Does the World Register of Marine Species Contribute to This?

Report Who played a key role during the development of our modern-day taxonomy and how does the World Register of Marine Species contribute to this? By Daisy ter Bruggen Module LKZ428VNST1 Project internship Van Hall Larenstein, Agora 1, 8934 AL Leeuwarden [email protected] Abstract: Our Western taxonomy officially began with Linnaeus. Nevertheless, equally important discoveries and research has been done long before the Linnaean system was introduced. Aristotle and Linnaeus are two of the most well-known names in history when discussing taxonomy and without them the classification system we use today might have never existed at all. Their interest, research and knowledge in nature was influenced by their upbringing and played a major factor in the running of their lives. Introduction The definition of taxonomy according to the Convention on Biological Diversity “Taxonomy is the science of naming, describing and classifying organisms and includes all plants, animals and microorganisms of the world” (2019). Aristotle and Linnaeus are two of the most well-known names in history when discussing taxonomy and without them the classification system we use today might have never existed at all. Their interest, research and knowledge in nature was influenced by their upbringing and played a major factor in the running of their lives. Aristotle (384 BC-322 BC) was a Greek philosopher. He was born in Stagira, a small town in Macedonia, Northern Greece (Voultsiadou, Gerovasileiou, Vandepitte, Ganias, & Arvanitidis, 2017). At the age of seventeen, he went to Athens, and studied in Plato’s Academy for 20 years. Which is where he developed his passion to study nature. -

Downloaded from USGS Earth Resources Observation and Science (EROS) Center (

Cover Page The following handle holds various files of this Leiden University dissertation: http://hdl.handle.net/1887/61828 Author: Bosch, D.M. Title: Molluscs in the Levantine Upper Palaeolithic: implications for modern human diets and subsistence behavior Issue Date: 2018-05-03 Chapter 5 The Ksâr ‘Akil (Lebanon) mollusc assemblage: Zooarchaeological and taphonomic investigations Published in: Quaternary International, 390, 85-10. 125 126 Quaternary International 390 (2015) 85–101 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Quaternary International journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/quaint The Ksâr ’Akil (Lebanon) mollusc assemblage: Zooarchaeological and taphonomic investigations a, b a Marjolein D. Bosch ∗,FrankP.Wesselingh,MarcelloA.Mannino a Department of Human Evolution, Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology, Deutscher Platz 6, 04103 Leipzig, Germany b Naturalis Biodiversity Center, Darwinweg 2, Postbus 9517, 2300 RA, Leiden, The Netherlands article info abstract Article history: Shells of marine molluscs exploited by prehistoric humans constitute archives of palaeoecological and Available online 7 August 2015 palaeoclimatic data, as well as of human behaviour in coastal settings. Here we present our investigations on the mollusc assemblage from Ksâr ’Akil (Lebanon), a key site in southwestern Asia occupied during Keywords: Archaeomalacology the Middle and Upper Palaeolithic. The site plays an important role in understanding modern human Upper Palaeolithic dispersals into Eurasia. Taxa from intertidal rocky shore, subtidal soft bottom, and rocky littoral habitats Hunter–gatherers dominate the marine component of the invertebrate assemblage. Terrestrial snails indicate wooded and Ksâr ’Akil open half shaded habitats in the vicinity of the site. Species composition suggests that these habitats Eastern Mediterranean were present throughout the Upper Palaeolithic. -

Phase Field Approach to Polycrystalline Solidification

Phase-field modeling of biomineralization in mollusks and corals: Microstructure vs. formation mechanism László Gránásy,1,2,§ László Rátkai,1 Gyula I. Tóth,3 Pupa U. P. A. Gilbert,4 Igor Zlotnikov,5 and Tamás Pusztai1 1 Institute for Solid State Physics and Optics, Wigner Research Centre for Physics, P. O. Box 49, H1525 Budapest, Hungary 2 Brunel Centre of Advanced Solidification Technology, Brunel University, Uxbridge, Middlesex, UB8 3PH, UK 3 Department of Mathematical Sciences, Loughborough University, Loughborough, Leicestershire LE11 3TU, UK 4 Departments of Physics, Chemistry, Geoscience, Materials Science, University of Wisconsin–Madison, Madison, WI 53706, USA. 5 B CUBE–Center for Molecular Bioengineering, Technische Universität Dresden, 01307 Dresden, Germany § Corresponding author: [email protected] While biological crystallization processes have been studied on the microscale extensively, models addressing the mesoscale aspects of such phenomena are rare. In this work, we investigate whether the phase-field theory developed in materials science for describ- ing complex polycrystalline structures on the mesoscale can be meaningfully adapted to model crystallization in biological systems. We demonstrate the abilities of the phase-field technique by modeling a range of microstructures observed in mollusk shells and coral skeletons, including granular, prismatic, sheet/columnar nacre, and sprinkled spherulitic structures. We also compare two possible micromechanisms of calcification: the classical route via ion-by-ion addition from a fluid state and a non-classical route, crystallization of an amorphous precursor deposited at the solidification front. We show that with appropriate choice of the model parameters microstructures similar to those found in biomineralized systems can be obtained along both routes, though the time- scale of the non-classical route appears to be more realistic. -

1 Seasonal Records of Palaeoenvironmental Change and Resource Use from Archaeological 2 Assemblages 3 4 Amy L

1 Seasonal records of palaeoenvironmental change and resource use from archaeological 2 assemblages 3 4 Amy L. Prendergast1, Alexander J. E. Pryor2, Hazel Reade3, Rhiannon E. Stevens3 5 6 1 School of Geography, The University of Melbourne, Melbourne, Australia 7 2 Department of Archaeology, University of Exeter, UK 8 3 Institute of Archaeology, University College London, London, UK 9 10 Abstract 11 12 Seasonal climate variability can affect the availability of food, water, shelter and raw 13 materials. Therefore, robust assessments of relationships between environmental change and 14 changes in human behaviour require an understanding of climate and environment at a 15 seasonal scale. In recent years, many advances have been made in obtaining seasonally- 16 resolved and seasonally-focused palaeoenvironmental data from proxy records. If these proxy 17 records are obtained from archaeological sites, they offer a unique opportunity to reconstruct 18 local climate variations that can be spatially and temporally related to human activity. 19 Furthermore, the analysis of various floral and faunal remains within archaeological sites 20 enables reconstruction of seasonal resource use and subsistence patterns. This paper provides 21 an overview of the growing body of research on seasonal palaeoenvironmental records and 22 resource use from archaeological contexts as well as providing an introduction to a special 23 issue on the same topic. This special issue of Journal of Archaeological Science Reports 24 brings together some of the latest research on generating seasonal-resolution and seasonally- 25 focused palaeoenvironmental records from archaeological sites as a means to assessing 26 human-environment interaction. The papers presented here include studies on archaeological 27 mollusc shells, otoliths, bones and plant remains using geochemical proxies including stable 28 isotopes (δ18O, δ13C, δ15N) and trace elements (Mg/Ca). -

The Bivalve Shells Pinctada Fucata and Anodonta Cygnea and the Gastropod Shell Phorcus Turbinatus

COMPARISON OF THE MICROSTRUCTURE OF THE BIVALVE SHELLS PINCTADA FUCATA AND ANODONTA CYGNEA AND THE GASTROPOD SHELL PHORCUS TURBINATUS Dissertation Zur Erlangung des Dokt or grades an der Fakultät für Mathematik, Informatik und Naturwissenschaften im Fachbereich Geowissenschaften der Universität Hamburg vorgelegt von J i anhan He aus J i ngzhou, P.R.C hi na Hamburg, 2018 Vorsitzende/r: Prof. Dr. Ulrich Bismayer Erstgutachter: Prof. Dr. Ulrich Bismayer Zweitgutachter: Prof. Dr. Jochen Schlüter Datum der Disputation: 05. Juni 2018 Eidesstattliche Versicherung Declaration on oath according to § 7 (4) doctoral degree regulations of MIN faculty Hiermit erkläre ich an Eides statt, dass ich die vorliegende Dissertationsschrift selbst verfasst und keine anderen als die angegebenen Quellen und Hilfsmittel benutzt habe. I hereby declare, on oath, that I have written the present dissertation by my own and have not used other than the acknowledged resources and aids. Hamburg 27.03.2018 Hamburg, den / city and date Unterschrift / signature ‘Many years later as he faced the firing squad, Colonel Aureliano Buendía was to remember that distant afternoon when his father took him to discover ice.’ Gabriel García Márquez, One Hundred Years of Solitude. For my father Shunyou He and my mother Zhengxiang Lei. C OMPARISON OF THE MIC ROSTRUCTURE OF THE B IVALVE SHELLS P INCTADA FUCATA A N D A NODONTA CYGNEA AND THE GASTROPOD SH E L L P HORCUS TURBINATUS Content Content Abstract .................................................................................................................................... -

Phorcus Sauciatus) E (Ii) a Avaliação Dos Efeitos Da Regulamentação Da Apanha De Lapas Nas Populações Exploradas (Patella Aspera, Patella Candei)

DMTD Key Exploited Species as Surrogates for Coastal Conservation in an Oceanic Archipelago: Insights from topshells and limpets from Madeira (NE Atlantic Ocean) DOCTORAL THESIS Ricardo Jorge Silva Sousa DOCTORATE IN BIOLOGICAL SCIENCES May | 2019 Key Exploited Species as Surrogates for Coastal Conservation in an Oceanic Archipelago: Insights from topshells and limpets from Madeira (NE Atlantic Ocean) DOCTORAL THESIS Ricardo Jorge Silva Sousa DOCTORATE IN BIOLOGICAL SCIENCES Note: The present thesis presents the results of work already published (chapters 2 to 11), in accordance with article 3 (2) and article 6 (2) of the Specific Regulation of the Third Cycle Course in Biological Sciences of the University of Madeira. Resumo As lapas e os caramujos estão entre os herbívoros mais bem adaptados ao intertidal do Atlântico Nordeste. Estas espécies-chave fornecem serviços ecossistémicos valiosos, desempenhando um papel fundamental no equilíbrio ecológico do intertidal e têm um elevado valor económico, estando sujeitas a altos níveis de exploração e representando uma das atividades económicas mais rentáveis na pesca de pequena escala no arquipélago da Madeira. Esta dissertação visa preencher as lacunas existentes na história de vida e dinâmica populacional destas espécies, e aferir os efeitos da regulamentação da apanha nos mananciais explorados. A abordagem conservacionista implícita ao longo desta tese pretende promover: (i) a regulamentação adequada da apanha de caramujos (Phorcus sauciatus) e (ii) a avaliação dos efeitos da regulamentação da apanha de lapas nas populações exploradas (Patella aspera, Patella candei). Atualmente, os mananciais de lapas e caramujos são explorados perto do rendimento máximo sustentável, e a monitorização e fiscalização são fundamentais para evitar a futura sobre-exploração. -

Calibration of the Oxygen Isotope Ratios of the Gastropods Patella Candei Crenata and Phorcus Atratus As High-Resolution Paleoth

Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 487 (2017) 251–259 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/palaeo Calibration of the oxygen isotope ratios of the gastropods Patella candei MARK crenata and Phorcus atratus as high-resolution paleothermometers from the subtropical eastern Atlantic Ocean ⁎ Wesley G. Parkera, , Yurena Yanesa, Donna Surgeb, Eduardo Mesa-Hernándezc a Department of Geology, University of Cincinnati, Cincinnati, OH 45221, USA b University of North Carolina, Department of Geological Sciences, 104 South Road, CB #3315, Chapel Hill, NC 27514, USA c Departamento de Prehistoria, Antropología e Historia Antigua, Universidad de La Laguna, La Laguna, Tenerife, Canary Islands, Spain ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: The oxygen isotope composition (δ18O) recorded in shells of the gastropods Patella candei crenata and Phorcus Temperature proxy atratus from the Canary Islands (27–29°N) potentially provide invaluable high-resolution paleoclimatic data. Limpet However, because these two species have never been studied isotopically, it is necessary to calibrate and validate Canary Islands this approach by using live-collected specimens that can be compared to present-day climate data. For P. candei Climate crenata, live organisms were collected at 15-day intervals for nearly one year (between 2011 and 2012) from the Gastropoda rocky-intertidal coast of SE Tenerife along with sea surface temperatures (SST) and seawater δ18O values. The δ18O values of the last growth episode along the shell growth margin, representing the conditions when or- ganisms were collected, illustrate that P. candei crenata δ18O values were 1.3 ± 0.2‰ higher than expected values from isotopic equilibrium. This finding resulted in estimated SST 5.7 ± 0.6 °C lower than observed values.