SC03-1251 Tyne, Etc., Et Al. Vs. Time Warner

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

J2P and P2J Ver 1

3 `- General News Labels, RIAA Protest Total LP Airings 'VFW YORK - lo oirrualts Un- Ing ffte rimas tu enable fans tu set Up lease *kohl, and ',sea schedule the. stones of radio', inn programming l hryatt. Records; Ahnw4 Erregun, pnvaskrrad show cd sotidarits, the their taping aquipmenl. programs free of c erclal Utter and ahllils to attract audiences and Allantic Records; Gil Friesen, A &M heads of all the mar. branch and in Lottko SUIS Indlsklual record rupi lens, cunmurcial adse1114et . Record.; Kenneth (;amble, Phila- dependent record .companies hate is- companies hale contacted radio +la- -Some gib a step further will, paid ' 1 hl+ Is an alhwal f record es- delphia inlarnallonal Records; Stun. sued a tatement condemning nwarm Iluns dhol the praclke, but he sass newspaper ads listing all lilies e11111 es lo radl l eseculives lu stop ley Gurlikos, RIAA; BS. !towel! Jr., practice to radio Malins in Mooed hsowl this ..peal, RIAA Is retsina and falladea l hours, again with the fostering the h taping of record- Navhb ro Records; Alan Livingston, casting complete I Ps without inter on the radio stations lu teary 11 Is In promise of ram cnnllnarcials. ings ... In hall the eonnlerelal free 211th Century-Fos Records: Bruce ruplla.l which allows Im ea.) Mom their own Interest 10 discourage broadcasting of new release records I.undrrll, CBS Records, lapina. home lapina. Ile sass his Irganita RKO Stops- See p,6 as ball for hume -toper Ilsteni- r.IIlp. Also: JYrrell McCracken. Word The statement, released Ihr gh tiny at this Ilnw has no plans to fol. -

Young Americans to Emotional Rescue: Selected Meetings

YOUNG AMERICANS TO EMOTIONAL RESCUE: SELECTING MEETINGS BETWEEN DISCO AND ROCK, 1975-1980 Daniel Kavka A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF MUSIC August 2010 Committee: Jeremy Wallach, Advisor Katherine Meizel © 2010 Daniel Kavka All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Jeremy Wallach, Advisor Disco-rock, composed of disco-influenced recordings by rock artists, was a sub-genre of both disco and rock in the 1970s. Seminal recordings included: David Bowie’s Young Americans; The Rolling Stones’ “Hot Stuff,” “Miss You,” “Dance Pt.1,” and “Emotional Rescue”; KISS’s “Strutter ’78,” and “I Was Made For Lovin’ You”; Rod Stewart’s “Do Ya Think I’m Sexy“; and Elton John’s Thom Bell Sessions and Victim of Love. Though disco-rock was a great commercial success during the disco era, it has received limited acknowledgement in post-disco scholarship. This thesis addresses the lack of existing scholarship pertaining to disco-rock. It examines both disco and disco-rock as products of cultural shifts during the 1970s. Disco was linked to the emergence of underground dance clubs in New York City, while disco-rock resulted from the increased mainstream visibility of disco culture during the mid seventies, as well as rock musicians’ exposure to disco music. My thesis argues for the study of a genre (disco-rock) that has been dismissed as inauthentic and commercial, a trend common to popular music discourse, and one that is linked to previous debates regarding the social value of pop music. -

Ic/Record Industry July 12, 1975 $1.50 Albums Jefferson Starship

DEDICATED TO THE NEEDS IC/RECORD INDUSTRY JULY 12, 1975 $1.50 SINGLES SLEEPERS ALBUMS ZZ TOP, "TUSH" (prod. by Bill Ham) (Hamstein, BEVERLY BREMERS, "WHAT I DID FOR LOVE" JEFFERSON STARSHIP, "RED OCTOPUS." BMI). That little of band from (prod. by Charlie Calello/Mickey Balin's back and all involved are at JEFFERSON Texas had a considerable top 40 Eichner( (Wren, BMI/American Com- their best; this album is remarkable, 40-1/10 STARSHIP showdown with "La Grange" from pass, ASCAP). First female treat- and will inevitably find itself in a their "Tres Hombres" album. The ment of the super ballad from the charttopping slot. Prepare to be en- long-awaited follow-up from the score of the most heralded musical veloped in the love theme: the Bolin - mammoth "Fandango" set comes in of the season, "A Chorus Line." authored "Miracles" is wrapped in a tight little hard rock package, lust Lady who scored with "Don't Say lyrical and melodic grace; "Play on waiting to be let loose to boogie, You Don't Remember" doin' every- Love" and "Tumblin" hit hard on all boogie, boogie! London 5N 220. thing right! Columbia 3 10180. levels. Grunt BFL1 0999 (RCA) (6.98). RED OCTOPUS TAVARES, "IT ONLY TAKES A MINUTE" (prod. CARL ORFF/INSTRUMENTAL ENSEMBLE, ERIC BURDON BAND, "STOP." That by Dennis Lambert & Brian Potter/ "STREET SONG" (prod. by Harmonia Burdon-branded electrified energy satu- OHaven Prod.) (ABC Dunhill/One of a Mundi) (no pub. info). Few classical rates the grooves with the intense Kind, BMI). Most consistent r&b hit - singles are released and fewer still headiness that has become his trade- makers at the Tower advance their prove themselves. -

The Inside Story of Casablanca Records Larry Harris, Curt Gooch, Jeff Suhs - Book Free

[pdf] And Party Every Day: The Inside Story Of Casablanca Records Larry Harris, Curt Gooch, Jeff Suhs - book free Download PDF And Party Every Day: The Inside Story Of Casablanca Records Free Online, Download And Party Every Day: The Inside Story Of Casablanca Records E-Books, Read Best Book Online And Party Every Day: The Inside Story Of Casablanca Records, And Party Every Day: The Inside Story Of Casablanca Records Free Read Online, And Party Every Day: The Inside Story Of Casablanca Records Free Download, PDF And Party Every Day: The Inside Story Of Casablanca Records Popular Download, And Party Every Day: The Inside Story Of Casablanca Records Free Download, by Larry Harris, Curt Gooch, Jeff Suhs And Party Every Day: The Inside Story Of Casablanca Records, free online And Party Every Day: The Inside Story Of Casablanca Records, And Party Every Day: The Inside Story Of Casablanca Records Free PDF Online, And Party Every Day: The Inside Story Of Casablanca Records Ebook Download, And Party Every Day: The Inside Story Of Casablanca Records Book Download, Download And Party Every Day: The Inside Story Of Casablanca Records PDF, I Was So Mad And Party Every Day: The Inside Story Of Casablanca Records Larry Harris, Curt Gooch, Jeff Suhs Ebook Download, Read And Party Every Day: The Inside Story Of Casablanca Records Online Free, full book And Party Every Day: The Inside Story Of Casablanca Records, PDF And Party Every Day: The Inside Story Of Casablanca Records Free Download, And Party Every Day: The Inside Story Of Casablanca Records Ebooks, And Party Every Day: The Inside Story Of Casablanca Records Full Download, Read And Party Every Day: The Inside Story Of Casablanca Records Books Online Free, DOWNLOAD CLICK HERE kindle, mobi, azw, pdf Description: A fascinating read, one-off series by Richard Bower on how we have evolved from a humble start at Oxford University's School of Economics. -

Kiss Alive! Mp3, Flac, Wma

Kiss Alive! mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Rock Album: Alive! Country: US Released: 1975 Style: Hard Rock, Glam MP3 version RAR size: 1843 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1360 mb WMA version RAR size: 1451 mb Rating: 4.8 Votes: 356 Other Formats: XM MMF RA XM WAV VOX AU Tracklist Hide Credits Deuce A1 3:32 Written-By – Simmons* Strutter A2 3:12 Written-By – Simmons*, Stanley* Got To Choose A3 3:35 Written-By – Stanley* Hotter Than Hell A4 3:11 Written-By – Stanley* Firehouse A5 3:42 Written-By – Stanley* Nothin' To Lose B1 3:23 Written-By – Simmons* C'mon And Love Me B2 2:52 Written-By – Stanley* Parasite B3 3:21 Written-By – Frehley* She B4 6:42 Written-By – Simmons*, Coronel* Watchin' You C1 3:37 Written-By – Simmons* 100,000 Years C2 11:52 Written-By – Simmons*, Stanley* Black Diamond C3 5:21 Written-By – Stanley* Rock Bottom D1 3:08 Written-By – Frehley*, Stanley* Cold Gin D2 5:21 Written-By – Frehley* Rock And Roll All Nite D3 3:37 Written-By – Simmons*, Stanley* Let Me Go, Rock 'N Roll D4 5:09 Written-By – Simmons*, Stanley* Companies, etc. Phonographic Copyright (p) – Casablanca Record And Filmworks, Inc. Copyright (c) – Casablanca Records, Inc. Published By – Phonogram Printed By – Polygram Industries Messageries Mixed At – Electric Lady Studios Credits Design – Dennis Woloch Performer [Kiss] – Ace Frehley, Gene Simmons, Paul Stanley, Peter Criss Photography By – David Spindel, Fin Costello, John Kelly , Mike Martineau, Phillipe Morgan, Stephen Levy Producer, Engineer, Mixed By – Eddie Kramer Notes Recorded live during the Dressed To Kill tour. -

Thesis Writing Deliverables (Pdf)

DEFENSE SPEECH Discovering and listening to music has always been my biggest passion in life and my primary way of coping with my emotions. I think its main appeal to me since childhood has been the comfort it brings in knowing that at some point in time, another human felt the same thing as me and was able to survive and express it by making something beautiful. For my project, I recorded a 9 track album called Strange Machines while I was on leave of absence last year. This term, I created a 20 minute extended music video to accompany it. All of this lives on a page I coded on my personal website with some fun bonus content that I’ll scroll through at the end of this presentation. I’ll put the link in the comments so anyone who’s interested can check it out at their own pace. I have so much fun making music and feel proud when I have a cohesive finished product at the end. I’m not interested in becoming a virtuoso musician or a professional producer. A lot of trained musicians gatekeep, intimidate, and discourage amateurs. People mystify and mythologize the creative process as if it’s the product of some elusive, innate genius rather than practice, experimentation, and a simple love of music. As someone who’s work exists entirely as digital recordings, there’s no inherent reason for me to be an amazing guitar player who can play a song perfectly all the way through, as mistakes can be easily cut out and re-recorded. -

Second Kiss Free

FREE SECOND KISS PDF Natalie Palmer | 237 pages | 30 Nov 2010 | Tate Publishing & Enterprises | 9781616637675 | English | United States セカンド・キス (Second Kiss) | Vocaloid Lyrics Wiki | Fandom Well known for its members' face Second Kiss and stage outfits, the group rose to prominence in the mid-to-late s with its elaborate live performances, which featured fire breathingblood-spitting, smoking guitars, shooting Second Kiss, levitating drum kits, and pyrotechnics. The band has gone through several lineup changes, with Second Kiss and Simmons Second Kiss the only members to feature in every lineup. The original and best-known lineup consists of Stanley vocals and rhythm guitarSimmons vocals and bassFrehley lead guitar and vocalsand Criss drums and vocals. With their make-up and costumes, the band members took on the personae of comic book-style characters: the Starchild Stanleythe Demon Simmonsthe Spaceman or Space Ace Frehleyand the Catman Criss. Due to creative differences, both Second Kiss and Frehley had departed the group by InKiss began performing without makeup and costumes, thus marking the beginning of the band's "unmasked" era that would last for over a decade. The band Second Kiss a commercial resurgence during this era, with the Platinum-certified album Lick It Up successfully Second Kiss them to a new generation of fans, and its music videos received regular airplay on MTV. Eric Carrwho had replaced Criss indied in of heart cancer and was replaced by Eric Singer. In response to a wave of Kiss nostalgia in the mids, the original lineup re-united inwhich also saw the return of its makeup and stage costumes. -

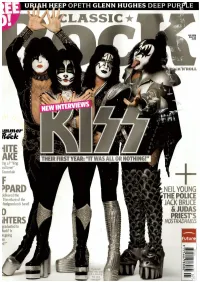

Iake ~F Ppard

\ \ I / / / I HllE' IAKE ving a f**king ood time!" Coverdale ~F PPARD NEIL YOUNG delivered the " The return of the THE POLICE e feelgood rock band! JACK BRUCE &JUDAS 0 PRIEST'S iHTERS NOSTRADAMUS : graduated to Rock? Is negoing :ise 1rd?" II _ a -=v"'J . ·nts Issue 120 Regulars~ 8 COMMUNICATION BREAKDOWN Rock's lippy-est letters page, 10THEDIRT The Jimi Hendrix sex tape; inside The Rolling Stones in 1969; interviews with Robin Trower, Opeth, Blue Oyster Cult and the hottest new bands: Howlin Rain, To-Mera and Jaded Sun. 25 EVERY HOME SHOULD HAVE ONE Wolfmother's Andrew Stockdale on the influence and terrifying effect of The Beatles' White Album, 26 THE STORIES BEHIND THE SONGS Investigated by the FBI, covered by every band, ever- the inside story of Louie Louie, 28Q&A "I've been playing since 1956!" Steve Miller looks back over several decades of joking, smoking and midnight toking, 71REVIEWED Triumphant new albums from Uriah Heep, Judas Priest, Opeth, Tom Petty's Mudcrutch, Glenn Hughes and Rush; Black Crowes & more caught live! 90 BUYER'S GUIDE The best ofNeil Young and where to find it 99RADAR Your essential guide to all the rock-related gigs on this month, WHITESNAKE: NEILZLOZOWER; KISS: NEIL ZlOZOWER/LYDIA CHRISS; NEIL YOUNG: ROSS GIMORE/REDFERNS COMMUNICATION ~ BllEAKDOWN ~ Send your letters to: Communication Breakdown, CLASSIC ROCK, Future, 2 Balcombe Street. London NWl 6NA, or email them to us at: oassicrock ii futurenet.co.uk. We regret we cannot reply to phone calls. For more letters and comment. visit www.classicrockmagazine.com. -

Giorgio Moroder Interview

This interview with GIORGIO MORODER, writer/producer of “I Feel Love,” was conducted by the Library of Congress on October 14, 2015. LOC: “I Feel Love” makes up the “future” section of Donna Summer’s 1977 album “I Remember Yesterday,” that you produced. Did you, from the beginning, aspire to create something “futuristic” sounding? Yes, I definitely wanted to explore it as a whole concept and come up with a sound that was of the future. I did it by only using synthesizers, because I thought it was the instrument that would be used in the future--be the instrument of the future. We used it, and only it, to create all the sounds. I wanted to try to imitate what people would do in 20 or 30 years. I used all digital sounds for the song, all of them coming from the computer. Everything except the voice was created by the Moog. The problem was I always composed at piano, with the chords. This time [with the Moog], I had to start with the tracks not the melody. So, I started with a bass line. It was a big, big job. First, I recorded a click, the tempo, about four notes in: dong dong dong dong. I just looped them. I got the sound I wanted by holding one note—let’s say C—and holding it then moving it to F and G…. The problem then is I had to stop and restart after every seven to eight seconds to retune the synth. But, once I had the chord structure, I then used a white noise generator and put it in the envelope [?] to make it sound like a high hat, a snare and many other instruments. -

Goodnight Saigon: Billy Joel’S Musical Epitaph to the Vietnam War

Touro Law Review Volume 32 Number 1 Symposium: Billy Joel & the Law Article 5 April 2016 Goodnight Saigon: Billy Joel’s Musical Epitaph to the Vietnam War Morgan Jones Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.tourolaw.edu/lawreview Part of the Law Commons, and the Other Music Commons Recommended Citation Jones, Morgan (2016) "Goodnight Saigon: Billy Joel’s Musical Epitaph to the Vietnam War," Touro Law Review: Vol. 32 : No. 1 , Article 5. Available at: https://digitalcommons.tourolaw.edu/lawreview/vol32/iss1/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ Touro Law Center. It has been accepted for inclusion in Touro Law Review by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ Touro Law Center. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Jones: Goodnight Saigon GOODNIGHT SAIGON: BILLY JOEL’S MUSICAL EPITAPH TO THE VIETNAM WAR Morgan Jones* Billy Joel adopted new personae and took on new roles in several songs on both 1982’s The Nylon Curtain1 and his penultimate studio album to date, 1989’s Storm Front.2 In what some have seen as an attempt to reach a more adult audience, to “move pop/rock into the middle age and, in the process, earn critical respect,”3 Joel put on new hats (literally, at times: his fedora-wearing balladeer appears prominently in the video for “Allentown”) for “Allentown” and “The Downeaster ‘Alexa’,” “Pressure” and “We Didn’t Start the Fire,” and “Goodnight Saigon” and “Leningrad.”4 Each of these pairs of songs saw Joel endeavoring to make statements about issues that were bigger than he and his own life, which was in stark contrast to his sources of inspiration for his earlier, more self-centered albums. -

Oh Happy Day” – the Edwin Hawkins Singers (1968) Added to the National Registry: 2005 Essay by Bill Carpenter (Guest Post)*

“Oh Happy Day” – The Edwin Hawkins Singers (1968) Added to the National Registry: 2005 Essay by Bill Carpenter (guest post)* Original label The Edwin Hawkins Singers If four-time Grammy Award winning singer, songwriter and choirmaster Edwin Hawkins had been a record label executive and had to pick his own radio singles, then his multi- million selling 1968 recording of “Oh, Happy Day” probably would not have become the global anthem that it became in the heart of the counterculture, civil rights and Jesus movements in the late sixties and early seventies. “My mother had an old hymnal and I had a knack for rearranging hymns,” Hawkins says of the song that first surfaced on his custom-made LP “Let Us Go into the House of the Lord.” The song was recorded at the Ephesians Church of God in Christ (COGIC) in his hometown of Oakland, CA to raise money for the church’s 40+-member youth choir to attend a convention. “‘Oh Happy Day’ was an old hymn and I rearranged it. It was actually one of the least likely songs to become a hit. There were some much stronger songs on there. We were going to hand-sell the album in the Bay Area. We ordered 500 copies. Lamont Bench, a Mormon guy, recorded that album on a two-track system. All 500 copies sold.” One of those albums fell into the hands of Abe “Voco” Keshishian, an influential DJ at KSAN 94.9 FM in the Bay area, who started to play “Oh Happy Day” on his “Lights Out San Francisco” blues and rock program in early 1969. -

House Music: How the Pop Industry Excused Itself from One of the Most Important Musical Movements of the 20Th Century

House Music: How the Pop Industry Excused Itself From One Of The Most Important Musical Movements of The 20th Century By Brian Lindgren MUSC 7662X - The History of Popular Music and Technology Spring 2020 18 May 2020 © Copyright 2020 Brian Lindgren Abstract In the words of house music legend Frankie Knuckles, house music was disco's revenge. What did he mean by that? In many important ways, house music continued where it left off when it was dramatically cast from American society in the now infamous Disco Demolition Night of July 1979. Riding on the wave of many important social upheavals of the 1960s, disco laid a few important foundations for dance music as we know it today. It also challenged the pop industry power-structure by creating new avenues for music to top the Billboard charts. However, in the final analysis the popularity of disco became its undoing. House music continued to ride on a few of the important waves of disco. The longstanding success of house, however, was in a new development: the independent artist/producer. Young people who began to experiment with early consumer electronic instruments were responsible for creating this new genre of music. This new and exciting sound took hold in Chicago, Detroit and the UK before spreading around the world as the sound we know today as house music. 1 Thirty eight years after the term "House Music" was coined in 1982, the genre has incontestably become a global musical and cultural phenomenon. Few genres in music history can claim this kind of influence.