The Public Sector Ombudsman in Greater China: Four “Chinese” Models of Administrative Supervision

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2019 International Religious Freedom Report

CHINA (INCLUDES TIBET, XINJIANG, HONG KONG, AND MACAU) 2019 INTERNATIONAL RELIGIOUS FREEDOM REPORT Executive Summary Reports on Hong Kong, Macau, Tibet, and Xinjiang are appended at the end of this report. The constitution, which cites the leadership of the Chinese Communist Party and the guidance of Marxism-Leninism and Mao Zedong Thought, states that citizens have freedom of religious belief but limits protections for religious practice to “normal religious activities” and does not define “normal.” Despite Chairman Xi Jinping’s decree that all members of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) must be “unyielding Marxist atheists,” the government continued to exercise control over religion and restrict the activities and personal freedom of religious adherents that it perceived as threatening state or CCP interests, according to religious groups, nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), and international media reports. The government recognizes five official religions – Buddhism, Taoism, Islam, Protestantism, and Catholicism. Only religious groups belonging to the five state- sanctioned “patriotic religious associations” representing these religions are permitted to register with the government and officially permitted to hold worship services. There continued to be reports of deaths in custody and that the government tortured, physically abused, arrested, detained, sentenced to prison, subjected to forced indoctrination in CCP ideology, or harassed adherents of both registered and unregistered religious groups for activities related to their religious beliefs and practices. There were several reports of individuals committing suicide in detention, or, according to sources, as a result of being threatened and surveilled. In December Pastor Wang Yi was tried in secret and sentenced to nine years in prison by a court in Chengdu, Sichuan Province, in connection to his peaceful advocacy for religious freedom. -

The Origins and Development of Taiwan's Policies Toward The

The Origins and Development of Taiwan’s Policies toward the Overseas Citizens’ Participation in Homeland Governance and Decision-Making Dean P. Chen, Ph.D. Assistant Professor of Political Science Ramapo College of New Jersey Presentations for the Center on Democracy, Development, and the Rule of Law Stanford University February 28, 2014 How International Relations (IR) Theories Matter? • Second-image reversed (Peter Gourevitch, 1978) – International systemic changes affect domestic politics – Domestic political actors and institutions filter the effects of international conditions, resulting in changes of interests, coalitions, norms, ideas, identities and policies • Constructivist theory of argumentative persuasion (Thomas Risse, 2000) – Interests and identities can be changed through the social interactive processes of argumentation, deliberation, and persuasion Main Argument • The Republic of China (ROC)/Taiwan’s policies toward overseas constituents have always been closely aligned with the government’s diplomatic objectives – From KMT’s pan-Chinese nationalism to Taiwan’s desire for a greater international space and political autonomy • Transformations of international politics inevitably shape the domestic political situations in ROC/Taiwan, which, then, impact policies toward the overseas community • Despite facing a rising People’s Republic of China (PRC), Taiwan’s democratization and rising Taiwanese consciousness have fostered a new set of identities, interests, and arguments that compete with Beijing’s “one China” principle -

Transitional Justice in Taiwan: Changes and Challenges

Washington International Law Journal Volume 28 Number 3 7-1-2019 Transitional Justice in Taiwan: Changes and Challenges Nien-Chung Chang-Liao Yu-Jie Chen Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.uw.edu/wilj Part of the Comparative and Foreign Law Commons Recommended Citation Nien-Chung Chang-Liao & Yu-Jie Chen, Transitional Justice in Taiwan: Changes and Challenges, 28 Wash. L. Rev. 619 (2019). Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.uw.edu/wilj/vol28/iss3/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Reviews and Journals at UW Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Washington International Law Journal by an authorized editor of UW Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Compilation © 2019 Washington International Law Journal Association TRANSITIONAL JUSTICE IN TAIWAN: CHANGES AND CHALLENGES Nien-Chung Chang-Liao* and Yu-Jie Chen** Abstract: Taiwan’s experience with transitional justice over the past three decades suggests that dealing with historical injustice is a dynamic and fluid process that is fundamentally shaped and constrained by the balance of power and socio-political reality in a particular transitional society. This Article provides a contextualized legal-political analysis of the evolution of Taiwan’s transitional justice regime, with special attention to its limits and challenges. Since Taiwan’s democratization began, the transitional justice project developed by the former authoritarian Chinese Nationalist Party (Kuomintang, KMT) has been rather disproportionately focused on restorative over retributive mechanisms, with the main emphasis placed on reparations and apology and little consideration of truth recovery and individual accountability. -

Inauguration of 2008 MIECF

Press Release No 4 23 th April 2008 Inauguration of 2008 MIECF The “2008 Macau International Environmental Co-operation Forum and Exhibition” (2008 MIECF) was inaugurated this morning (April 23) at The Cotai Strip Convention and Exhibition Centre of the Venetian Macao Resort Hotel. The event is hosted by the Government of the Macao Special Administrative Region, co-organized by Provincial and Regional Governments of the Pan-Pearl River Delta Region, and supported by the Ministry of Environmental Protection of the People's Republic of China. Mr. Edmund Ho, Chief Executive of Macau SAR, gave a speech in the opening ceremony, pointing out that water and energy are matters of concern for both the international community and the Macau citizenry. He stressed that Macau’s water and energy security hinges on the support of the Central Government, and that the SAR is dedicated to solving problems regarding salinity, energy conservation, and environmental protection awareness-raising, in order to attain sustainable development. The officiating guests accompanying the Chief Executive in the opening ceremony include Mr. Li Benjun, Deputy Director General of the Liaison Office of the Central People’s Government in the Macao SAR, Mr. Wan Yongxiang, Commissioner of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People’s Republic of China in the Macao SAR, Mr. Hu Siyi, Vice Minister of Ministry of Water Resources of the PRC, Mr. Xu Qinghua, Representative of the Minister of Ministry of Environmental Protection of the PRC, Mr. Su Zengtian, Vice Governor of the People’s Government of Fujian Province, Mr. Hong Lihe, Vice Governor of the People’s Government of Jiangxi Province, Mr. -

Country Advice

Country Advice China China – CHN38641 – Uyghur – Uighur – Detention documents – Tianjin detention centres 9 May 2011 1. Please provide an analysis of the situation in China for Uighurs now and in the reasonably foreseeable future. According to the last US Department of State report on human rights practices in China of April 2011 the Chinese government continued its severe cultural and religious repression of ethnic minorities in Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region (XUAR).1 It found that based on official Chinese media reports, 197 persons had died and 1,700 were injured during the July 2009 rioting in Urumqi – capital city of Xinjiang. In November 2009 eight ethnic Uyghurs and one ethnic Han were reported to have been executed without due process for crimes committed during the riots. By the end of 2010, 26 persons were reported to have been sentenced to death; nine others had received suspended death sentences. Of these, three were reportedly ethnic Hans and the rest were Uyghurs. In April 2010 a Uyghur woman became the second woman sentenced to death for involvement in the violence. In December 2010 a Uyghur journalist Memetjan Abdulla was sentenced to life in prison for transmitting information about the riots because he translated an article from a Chinese-language website and posted it on a Uyghur-language website. China Daily reported that, according to the president of the XUAR Supreme People's Court, courts in the XUAR had tried 376 individuals in 2010 for "crimes against national security" and their involvement in the July 2009 -

Sharpening the Sword of State Building Executive Capacities in the Public Services of the Asia-Pacific

SHARPENING THE SWORD OF STATE BUILDING EXECUTIVE CAPACITIES IN THE PUBLIC SERVICES OF THE ASIA-PACIFIC SHARPENING THE SWORD OF STATE BUILDING EXECUTIVE CAPACITIES IN THE PUBLIC SERVICES OF THE ASIA-PACIFIC Edited by Andrew Podger and John Wanna Published by ANU Press The Australian National University Acton ACT 2601, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at press.anu.edu.au National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Title: Sharpening the sword of state : building executive capacities in the public services of the Asia-Pacific / editors: Andrew Podger, John Wanna. ISBN: 9781760460723 (paperback) 9781760460730 (ebook) Series: ANZSOG series. Subjects: Public officers--Training of--Pacific Area. Civil service--Pacific Area--Personnel management. Public administration--Pacific Area. Pacific Area--Officials and employees. Pacific Area--Politics and government. Other Creators/Contributors: Podger, A. S. (Andrew Stuart), editor. Wanna, John, editor. Dewey Number: 352.669 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover design and layout by ANU Press. Cover photograph adapted from: ‘staples’ by jar [], flic.kr/p/97PjUh. This edition © 2016 ANU Press Contents Figures . vii Tables . ix Abbreviations . xi Contributors . xvii 1 . Public sector executive development in the Asia‑Pacific: Different contexts but similar challenges . 1 Andrew Podger 2 . Developing leadership and building executive capacity in the Australian public services for better governance . 19 Peter Allen and John Wanna 3 . Civil service executive development in China: An overview . -

Digital Authoritarianism and the Global Threat to Free Speech Hearing

DIGITAL AUTHORITARIANISM AND THE GLOBAL THREAT TO FREE SPEECH HEARING BEFORE THE CONGRESSIONAL-EXECUTIVE COMMISSION ON CHINA ONE HUNDRED FIFTEENTH CONGRESS SECOND SESSION APRIL 26, 2018 Printed for the use of the Congressional-Executive Commission on China ( Available at www.cecc.gov or www.govinfo.gov U.S. GOVERNMENT PUBLISHING OFFICE 30–233 PDF WASHINGTON : 2018 VerDate Nov 24 2008 12:25 Dec 16, 2018 Jkt 081003 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 C:\USERS\DSHERMAN1\DESKTOP\VONITA TEST.TXT DAVID CONGRESSIONAL-EXECUTIVE COMMISSION ON CHINA LEGISLATIVE BRANCH COMMISSIONERS Senate House MARCO RUBIO, Florida, Chairman CHRIS SMITH, New Jersey, Cochairman TOM COTTON, Arkansas ROBERT PITTENGER, North Carolina STEVE DAINES, Montana RANDY HULTGREN, Illinois JAMES LANKFORD, Oklahoma MARCY KAPTUR, Ohio TODD YOUNG, Indiana TIM WALZ, Minnesota DIANNE FEINSTEIN, California TED LIEU, California JEFF MERKLEY, Oregon GARY PETERS, Michigan ANGUS KING, Maine EXECUTIVE BRANCH COMMISSIONERS Not yet appointed ELYSE B. ANDERSON, Staff Director PAUL B. PROTIC, Deputy Staff Director (ii) VerDate Nov 24 2008 12:25 Dec 16, 2018 Jkt 081003 PO 00000 Frm 00002 Fmt 0486 Sfmt 0486 C:\USERS\DSHERMAN1\DESKTOP\VONITA TEST.TXT DAVID C O N T E N T S STATEMENTS Page Opening Statement of Hon. Marco Rubio, a U.S. Senator from Florida; Chair- man, Congressional-Executive Commission on China ...................................... 1 Statement of Hon. Christopher Smith, a U.S. Representative from New Jer- sey; Cochairman, Congressional-Executive Commission on China .................. 4 Cook, Sarah, Senior Research Analyst for East Asia and Editor, China Media Bulletin, Freedom House ..................................................................................... 6 Hamilton, Clive, Professor of Public Ethics, Charles Sturt University (Aus- tralia) and author, ‘‘Silent Invasion: China’s Influence in Australia’’ ............ -

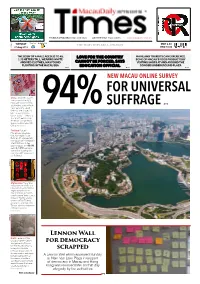

For Universal Suffrage

FOUNDER & PUBLISHER Kowie Geldenhuys EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Paulo Coutinho www.macaudailytimes.com.mo TUESDAY T. 26º/ 33º Air Quality Good MOP 8.00 3362 “ THE TIMES THEY ARE A-CHANGIN’ ” N.º 27 Aug 2019 HKD 10.00 THE BODY OF A MALE AGED 30 TO 40, LOVE FOR THE COUNTRY MAINLAND TOURISTS CAN EXPERIENCE 1.72 METERS TALL, WEARING WHITE SOME OF MACAU’S FOOD PRODUCTS BY AND RED CLOTHES, WAS FOUND CANNOT BE FORCED, SAYS VISITING SHOPS AT AND AROUND THE FLOATING IN THE MACAU SEA EDUCATION OFFICIAL GONGBEI UNDERGROUND PLAZA P2 P4 P8 AP PHOTO NEW MACAU ONLINE SURVEY FOR UNIVERSAL China allowed its yuan to sink yesterday and U.S. President Donald Trump P3 said the two sides will talk “very seriously” about SUFFRAGE their war over trade and technology following tit-for-tat tariff hikes and Trump’s threat to order American companies to 94% stop doing business with China. More on p11 Thailand Police in Phuket said yesterday that Norwegian Roger Bullman, 54, charged with manslaughter in the death of a British tourist has been released on 400,000 baht ($13,070) bail but is barred from leaving the country, with his passport confiscated. AP PHOTO Afghanistan Two yellow burqas are on display at a television station in Kabul, bright versions of the blue ghostlike garments some women in the capital still wear. For the young women at Zan TV they are relics, a reminder of a Taliban-ruled past that few of them can recall. More on p13 AP PHOTO Lennon Wall Brazil Leaders of the Group of Seven nations said yesterday [Macau for democracy time] they are preparing to help Brazil battle fires burning across the scrapped Amazon region and repair the damage as tens of A Lennon Wall which appeared Sunday thousands of soldiers at Nam Van Lake Plaza in support got ready to join the fight against blazes that have of democracy in Macau and Hong caused global alarm. -

Chapter 6 Hong Kong

CHAPTER 6 HONG KONG Key Findings • The Hong Kong government’s proposal of a bill that would allow for extraditions to mainland China sparked the territory’s worst political crisis since its 1997 handover to the Mainland from the United Kingdom. China’s encroachment on Hong Kong’s auton- omy and its suppression of prodemocracy voices in recent years have fueled opposition, with many protesters now seeing the current demonstrations as Hong Kong’s last stand to preserve its freedoms. Protesters voiced five demands: (1) formal with- drawal of the bill; (2) establishing an independent inquiry into police brutality; (3) removing the designation of the protests as “riots;” (4) releasing all those arrested during the movement; and (5) instituting universal suffrage. • After unprecedented protests against the extradition bill, Hong Kong Chief Executive Carrie Lam suspended the measure in June 2019, dealing a blow to Beijing which had backed the legislation and crippling her political agenda. Her promise in September to formally withdraw the bill came after months of protests and escalation by the Hong Kong police seeking to quell demonstrations. The Hong Kong police used increasingly aggressive tactics against protesters, resulting in calls for an independent inquiry into police abuses. • Despite millions of demonstrators—spanning ages, religions, and professions—taking to the streets in largely peaceful pro- test, the Lam Administration continues to align itself with Bei- jing and only conceded to one of the five protester demands. In an attempt to conflate the bolder actions of a few with the largely peaceful protests, Chinese officials have compared the movement to “terrorism” and a “color revolution,” and have im- plicitly threatened to deploy its security forces from outside Hong Kong to suppress the demonstrations. -

Chinese Politics in the Xi Jingping Era: Reassessing Collective Leadership

CHAPTER 1 Governance Collective Leadership Revisited Th ings don’t have to be or look identical in order to be balanced or equal. ڄ Maya Lin — his book examines how the structure and dynamics of the leadership of Tthe Chinese Communist Party (CCP) have evolved in response to the chal- lenges the party has confronted since the late 1990s. Th is study pays special attention to the issue of leadership se lection and composition, which is a per- petual concern in Chinese politics. Using both quantitative and qualitative analyses, this volume assesses the changing nature of elite recruitment, the generational attributes of the leadership, the checks and balances between competing po liti cal co ali tions or factions, the behavioral patterns and insti- tutional constraints of heavyweight politicians in the collective leadership, and the interplay between elite politics and broad changes in Chinese society. Th is study also links new trends in elite politics to emerging currents within the Chinese intellectual discourse on the tension between strongman politics and collective leadership and its implications for po liti cal reforms. A systematic analy sis of these developments— and some seeming contradictions— will help shed valuable light on how the world’s most populous country will be governed in the remaining years of the Xi Jinping era and beyond. Th is study argues that the survival of the CCP regime in the wake of major po liti cal crises such as the Bo Xilai episode and rampant offi cial cor- ruption is not due to “authoritarian resilience”— the capacity of the Chinese communist system to resist po liti cal and institutional changes—as some foreign China analysts have theorized. -

China (Includes Tibet, Hong Kong, and Macau) 2018 Human Rights Report

CHINA (INCLUDES TIBET, HONG KONG, AND MACAU) 2018 HUMAN RIGHTS REPORT EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The People’s Republic of China (PRC) is an authoritarian state in which the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) is the paramount authority. CCP members hold almost all top government and security apparatus positions. Ultimate authority rests with the CCP Central Committee’s 25-member Political Bureau (Politburo) and its seven-member Standing Committee. Xi Jinping continued to hold the three most powerful positions as CCP general secretary, state president, and chairman of the Central Military Commission. Civilian authorities maintained control of security forces. During the year the government significantly intensified its campaign of mass detention of members of Muslim minority groups in the Xinjiang Uighur Autonomous Region (Xinjiang). Authorities were reported to have arbitrarily detained 800,000 to possibly more than two million Uighurs, ethnic Kazakhs, and other Muslims in internment camps designed to erase religious and ethnic identities. Government officials claimed the camps were needed to combat terrorism, separatism, and extremism. International media, human rights organizations, and former detainees reported security officials in the camps abused, tortured, and killed some detainees. Human rights issues included arbitrary or unlawful killings by the government; forced disappearances by the government; torture by the government; arbitrary detention by the government; harsh and life-threatening prison and detention conditions; political prisoners; -

Combatting Corruption in the “Era of Xi Jinping”: a Law and Economics Perspective

Hastings International and Comparative Law Review Volume 43 Number 2 Summer 2020 Article 3 Summer 2020 Combatting Corruption in the “Era of Xi Jinping”: A Law and Economics Perspective Miron Mushkat Roda Mushkat Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/ hastings_international_comparative_law_review Part of the Comparative and Foreign Law Commons, and the International Law Commons Recommended Citation Miron Mushkat and Roda Mushkat, Combatting Corruption in the “Era of Xi Jinping”: A Law and Economics Perspective, 43 HASTINGS INT'L & COMP. L. Rev. 137 (2020). Available at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/hastings_international_comparative_law_review/vol43/ iss2/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Hastings International and Comparative Law Review by an authorized editor of UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 2 - Mushkat_HICLR_V43-2 (Do Not Delette) 5/1/2020 4:08 PM Combatting Corruption in the “Era of Xi Jinping”: A Law and Economics Perspective MIRON MUSHKAT AND RODA MUSHKAT Abstract Pervasive graft, widely observed throughout Chinese history but deprived of proper outlets and suppressed in the years following the Communist Revolution, resurfaced on massive scale when partial marketization of the economy was embraced in 1978 and beyond. The authorities had endeavored to alleviate the problem, but in an uneven and less than determined fashion. The battle against corruption has greatly intensified after Xi Jinping ascended to power in 2012. The multiyear antigraft campaign that has unfolded has been carried out in an ironfisted and relentless fashion.