I Don't Think That's Special to Curling

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Curling Canada • Ok Tire & Bkt Tires Continental Cup

CURLING CANADA • OK TIRE & BKT TIRES CONTINENTAL CUP, PRESENTED BY SERVICE EXPERTS HEATING, AIR CONDITIONING AND PLUMBING • MEDIA GUIDE 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS GENERAL INFORMATION BOARD OF GOVERNORS & NATIONAL STAFF 3 MEDIA INFORMATION 4 CURLING CANADA PHOTOGRAPHY GUIDELINES 5 TV NON-RIGHTS HOLDERS 6 EVENT INFORMATION FACT SHEET 7 SCHEDULE OF EVENTS 9 COMPETITION FORMAT & RULES 10 2020 OK TIRE & BKT TIRES CONTINENTAL CUP ANNOUNCEMENT 15 TEAMS & PLAYERS INFORMATION TEAM CANADA ROSTER 17 TEAM EUROPE ROSTER 17 PLAYER NICKNAMES 18 WOMEN’S PLAYER FACT SHEET 19 MEN’S PLAYER FACT SHEET 20 TEAM CANADA BIOS 21 TEAM CAREY 21 TEAM FLEURY 25 TEAM HOMAN 28 TEAM BOTTCHER 32 TEAM EPPING 35 TEAM KOE 39 TEAM CANADA COACH BIOS 43 TEAM EUROPE BIOS 46 TEAM HASSELBORG 46 TEAM MUIRHEAD 50 TEAM TIRINZONI 53 TEAM DE CRUZ 56 TEAM EDIN 59 TEAM MOUAT 63 TEAM EUROPE COACH BIOS 66 CURLING CANADA • OK TIRE & BKT TIRES CONTINENTAL CUP, PRESENTED BY SERVICE EXPERTS HEATING, AIR CONDITIONING AND PLUMBING • MEDIA GUIDE 2 BOARD OF GOVERNORS & NATIONAL STAFF CURLING CANADA 1660 Vimont Court Orléans, ON K4A 4J4 TEL: (613) 834-2076 FAX: (613) 834-0716 TOLL FREE: 1-800-550-2875 BOARD OF GOVERNORS John Shea, Chair Angela Hodgson, Governor Donna Krotz, Governor Amy Nixon, Governor George Cooke, Governor Cathy Dalziel, Governor Paul Addison, Governor Chana Martineau, Governor Sam Antila, Governor Mitch Minken, Governor NATIONAL STAFF Katherine Henderson, Chief Executive Officer Louise Sauvé, Administrative Assistant Bill Merklinger, Executive Director, Corporate Services Jacob Ewing, -

High on the Hog

High on the hog Kevin Mitchell The StarPhoenix While world-champion skip Randy Ferbey competition) . you could be asking for gushed this week about plans to adopt an trouble. All hell could break loose." electronic hog-line detector for the 2004 Brier, Kevin Martin pulled out a big, red But Ferbey, who tested the device when he Stop sign and started swinging. played at the Cup, endorses it enthusiastically. His distaste for hog-line Martin is skeptical -- to put it mildly -- after judges is well known, especially after a learning about the Canadian Curling blow-up at the 2001 world championships Association's decision to use the new that saw him get three rocks pulled in a 6-5 technology effective immediately. The semi-final loss to Switzerland's Christof detector, designed by a Saskatoon Schwaller. engineering firm, was tested in top-flight competition for the first time at last Scotland's Sheila Swan was the only curler weekend's Continental Cup, and it will be to activate the small red LED lights on the used at all CCA championships this season, handle during last weekend's Cup. including the Brier and Scott Tournament of Hearts. "It's a wonderful device," Ferbey said from his Edmonton home. "I give it five out of The CCA is so sure of its reliability it won't five. I see no problems with it, and it was even bother bringing in human judges as 100 per cent foolproof. I didn't hear one backups. complaint about it. But Martin, who hadn't heard about the plan "It basically confirms what we believe about until this week, objects on several different curling, is that people generally don't go levels. -

Dec 5 Morning Cup.Indd

Morning Issue 5 – Sunday, December 5, 2010 • An Offi cial Publication of the Canadian Curling Association. Here’s the deal: Cheryl Bernard, Carolyn Darbyshire and Cori Morris have qualified for their first Canada Cup women’s final. Clean sweep? ■ Kevin Martin seeks his fourth ■ Cheryl Bernard, Stefanie Lawton Canada Cup title in a classic are on a collision course . confrontation with Glenn Howard with a $25,000 payday at stake Page 2 Page 3 Marc Try the Make Your Day! Kennedy Single Day Passes are Also Available! If weekdays work better for your schedule, sample Half Cup! our day passes on Thursday and Friday. This is the package that puts you in the heat of the action all day Saturday and all day Sunday… $ when all the big points are on the line! 69 Includes GST & service charges. For tickets call or order online $ 780.451.8000 165Includes GST & service charges. +BOVBSZo t4FSWVT$SFEJU6OJPO1MBDF Page 2 Sunday, December 5, 2010 Hello, stranger: Martin, Howard to meet in final Larry Wood but then John did. And John and Todd Kimberley didn’t play very well last Morning Cup Editors night (in their pool-play fi - Men’s nale against Randy Ferbey), eamwork is prov- so then Marc did. So it’s all Final ing to be the key up to somebody else.” Today Tfor Kevin Martin’s Which is to say, it’s a defending Olympic cham- team game. 12:30 p.m. — pion quartet as they head Howard, whose record Kevin Martin into today’s 12:30 p.m. against Martin is far from (6-0, A1-B1 championship fi nal in the scintillating — 0-for-6 in Canada Cup of Curling at the Tim Hortons Brier, winner) vs. -

2018Annual Report

2018 ANNUAL REPORT MISSION already hard at work to make sure we continue winning significant strides forward in their competitive careers To encourage and facilitate medals. Preferably gold! but also a wonderful showcase in which to display We are also incredibly proud of our Canadian their talents. the growth and development Paralympic wheelchair team. In fact, the bronze medal it Our focus isn’t just on high performance, though. of curling in co-operation won at the Winter Paralympics may have been the This coming season, after a very successful pilot, we’re feel-good story of the year. planning to introduce Curling Canada’s Hit Draw Tap with our network of affiliates. message FROM THE CHIEF When I pause and take the entire 2017-18 season program — a youth skills competition in which kids aged into account, it was, in fact, a magnificent year for teams six to 13 compete as individuals. They will all perform EXECUTIVE OFFICER wearing the Maple Leaf. three different shots — a hit, a draw and a tap — and the Teams skipped by Tyler Tardi and Kaitlyn Jones gave difficulty of the skills are modified based on the age of VISION us a gold-medal sweep at the World Junior Curling the child. It’s a wonderful program that focuses just as In the year 2014 and Championships in Scotland. much on fun as it does on skill development. AS I LOOK BACK ON THE 2017-18 CURLING SEASON, And then Jennifer Jones won gold on home ice at the Our feeder system is extremely important to the future beyond, curling in Canada I see so many reasons to be proud of what we have Ford Worlds in North Bay, Ontario, where sellout crowds of our sport and we have developed a world-class system — from the grassroots accomplished by working together for our sport. -

361˚ World Men's Curling Championship 2018 74,829 0 25,000 50,000 75,000 100,000 125,000 150,000 175,000 200,000

GSI Event Study 361˚ World Men’s Curling Championship 2018 Las Vegas, USA 31 March – 8 April 2018 GSI EVENT STUDY / 361˚ WORLD MEN’S CURLING CHAMPIONSHIP 2018 GSI Event Study 361˚ World Men’s Curling Championship 2018 Las Vegas, USA This Event Study is subject to copyright agreements. No part of this Event Study may be reproduced distributed or transmitted in any form or by any means or PUBLISHED NOVEMBER 2018 stored in any retrieval system of any nature without prior written permission. Application for permission for use of copyright material shall be made to BY SPORTCAL GLOBAL Sportcal Global Communications Ltd (“Sportcal”). COMMUNICATIONS LTD Sportcal has prepared this Event Study using reasonable skill, care and diligence for the sole and confidential use of the World Curling Federation (“WCF”) and the Reno Tahoe Winter Games Coalition (“LOC”) for the purposes set out in the Authors Event Study. Sportcal does not assume or accept or owe any responsibility or Andrew Horsewood, Colin Stewart duty of care to any other person. Any use that a third party makes of this Event Study or reliance thereon or any decision made based on it, is the responsibility of such third party. Research and editorial support The Event Study reflects Sportcal’s best judgement in the light of the information Ezechiel Abatan, Edward Frain, Krzysztof available at the time of its preparation. Sportcal has relied upon the Kropielnicki, Beth McGuire, Tim Rollason completeness, accuracy and fair presentation of all the information, data, advice, opinion or representations (the “Information”) obtained from public sources and from the WCF, LOC and various third-party providers. -

Season of Champions

Season of Champions 2010-11 FACT BOOK Season of Champions FACT BOOK The 2010-11 Season of Champions Fact Book is published by the Canadian Curling Association. Reproduction in whole or in part without the written permission of the publisher is prohibited. World Curling Federation Management Committee . 4 2009-10 SEASON IN REVIEW Canadian Curling Association Canadian Curling Pre-Trials . 20 Board of Governors . 7 The Mixed . 24 Canadian Curling Association Tim Hortons Administration . 8 Canadian Curling Trials . 26 M&M Meat Shops 2010-11 Season of Champions . 11 Canadian Juniors . 30 Season of Champions Contacts . 12 Scotties Tournament of Hearts . 36 Olympic Winter Games . 40 Special Events . 13 Tim Hortons Brier . 44 Season of Champions Officials . 14 World Juniors . 48 Paralympic Winter Games . 52 Canadian Curling Association Awards . 16 Canadian Wheelchair . 53 Ford World Women’s . 54 Ford Hot Shots . 18 World Financial Group Canadian Seniors . 58 Thanks For The Memories . 72 Canadian Masters . 62 Canadian Curling Hall of Fame . 74 World Men’s . 64 Past Presidents. 82 World Mixed Doubles . 69 World Seniors . 70 Honorary Life Members . 84 Canadian Curling Reporters . 88 MEDIA INFORMATION Questions on any aspect of curling should be World Financial Group directed to Warren Hansen, P.O. Box 41099, Continental Cup Profiles. 90 2529 Shaughnessy Street, Port Coquitlam, British Columbia V3C 5Z9, telephone (604) 941-4330; 2009-10 AGM In Brief . 97 fax (604) 941-4332; email to [email protected]. 2010-11 TSN Broadcast Guide . 98 Members of the media seeking information pertaining to former Canadian or world championships, should contact Larry Wood Editor: Laurie Payne • Managing editor: Warren in Calgary at (403) 281-5300. -

Jennifer Jones, Brad Jacobs and Brent Laing to Join Randy Ferbey at 2Nd Annual Everest- Ferbey National Pro Am

Jennifer Jones, Brad Jacobs and Brent Laing to join Randy Ferbey at 2nd annual Everest- Ferbey National Pro Am Randy Ferbey announced the A-List line up in an on-air interview during TSNs broadcast of the 2016 WFG Continental Cup in Las Vegas. FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE. January 18, Toronto ON -- Hall-of-Famer and four-time world curling champion Randy Ferbey announced that Jennifer Jones will be returning as the opposing skip in the 2nd annual Everest-Ferbey National Pro Am. In addition to Jones, renowned curlers Brad Jacobs and Brent Laing will also be competing in the Pro Am. Ferbey made the announcement in an interview with the voice of Canadian curling, Vic Rauter, during TSN’s primetime broadcast of the Continental Cup in Las Vegas. Footage of the 90 second interview can be viewed here. The announcement peaked excitement for the Pro Am – now in its 2nd year - a signature event capping off the 2016 Everest Canadian Senior Curling Championships in Digby, NS. Designed to generate awareness for seniors curling in Canada, the Everest-Ferbey National Pro Am will bring the impressive line-up of Pro curlers to play with senior curling contest winners of all skill levels across the country. Since November, participants at registered curling clubs have been entering the contest for a chance to win a VIP trip to the 2016 Everest Canadian Seniors, and to curl with Randy Ferbey, along with the recently announced pros. Ferbey partnered with Everest Funeral Planning and Concierge Service, the title sponsor of the Canadian Senior Men’s and Women’s Curling Championships, to create the Pro Am event in 2015. -

Everest Partners with Curling Canada and TSN to Celebrate Memorable

PRESS RELEASE Everest Partners with Curling Canada and TSN to Celebrate Memorable Curling Moments Fans will get a glimpse into the most significant moments for Canada’s top curlers FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE. MARCH 6, 2021, Calgary, AB --- In partnership with Curling Canada and TSN, Everest is bringing fans the moments that matter to Canada’s most iconic curlers. The Moments that Matter series will air on TSN in Canada and ESPN3 streaming in the US during the Tim Hortons Brier, Home Hardware Canadian Mixed Doubles Championship and BKT Tires & OK Tire World Men's Curling Championship and will feature the most important curling moments through the years as recounted by an A-list group of curlers, including: • Cheryl Bernard • Kerri Einarson • John Epping • Randy Ferbey • Al Hackner • Rachel Homan • Russ Howard • Brad Jacobs ● Jennifer Jones ● Kevin Koe “Everest has always been proud to support Canadian curling and helping create moments for curlers across the country through our sponsorship of the Everest Canadian Seniors Championships, the Everest Curling Club Championships, the Everest Curling Challenge on TSN, the Everest-Ferbey National Pro Am and the TSN All-Star Curling Skins,” CEO Mark Duffey says. “This series is another way Everest fosters and celebrates the unique culture of community and caring that runs deep through this special sport.” “There’s no sport like curling when it comes to celebrating our history, especially when there have been so many memorable moments involving Canadian athletes at championship events” says Katherine Henderson, Chief Executive Officer of Curling Canada. “Like all Canadian curling fans, I look forward to reliving these memories, and feeling the chills go down my spine as we watch these Moments That Matter, and we appreciate the support of Everest in making this happen.” Everest is a sponsor of the Curling’s Capital event happening in the hub city of Calgary, which is being held without fans this year. -

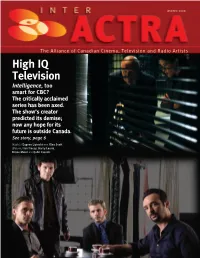

High IQ Television Intelligence, Too Smart for CBC? the Critically Acclaimed Series Has Been Axed

WINTER 2008 The Alliance of Canadian Cinema, Television and Radio Artists High IQ Television Intelligence, too smart for CBC? The critically acclaimed series has been axed. The show’s creator predicted its demise; now any hope for its future is outside Canada. See story, page 6 (Right:) Eugene Lipinski and Klea Scott. (Below:) Ian Tracey, Darcy Laurie, Shane Meier and John Cassini. 55023-1 Interactra.indd 1 3/13/08 10:56:25 AM By Richard Hardacre How do I know thee? Let me count the ways.(1) With some taxi drivers there’s much I had indeed piqued his interest. He Negotiating Committee will be counting more than meets the eye. If, like me, you told me that he’d been a professional on your support. We will achieve the very happen to have conversations with many Engineer in his native Morocco. He asked best deal for you that we possibly can – we of them between the Ottawa airport or me if I had been on strike last winter, are not new to this world now. train station and various Committee and he wondered what that was all about. Negotiating our collective agreements, rooms, Ministers’ offices, anterooms of When I explained how we could not just and building the campaign for Canadian bureaucrats around Parliament Hill, well accept a ‘kiss-off’ for our work distributed film and television programming are two then you occasionally might tune into an throughout the globe via new media, and of the biggest priorities of ACTRA. interesting frequency. that contrary to the honchos of the asso- As there will also likely be a Federal On one slushy, rush-hour, after I began ciations of producers, there was indeed election looming soon, we will make the in Canada’s other official language, my money being generated on the Internet, issues of foreign ownership limits on our cabbie inquired about my occupation. -

December 1, 2019 • Sobeys Arena, Leduc Recreation Centre • Leduc, Alberta

HOME HARDWARE CANADA CUP SOUVENIR PROGRAM PRESENTED BY NOVEMBER 27 – DECEMBER 1, 2019 • SOBEYS ARENA, LEDUC RECREATION CENTRE • LEDUC, ALBERTA CC19_Cover.indd 1 2019-10-30 5:30 PM NEVER STOP GROWING At Pioneer, we believe in growth. Growth of crops, people and the communities we’re proud to be part of. That’s why we continuously push the limits to provide Western Canadian growers with the best crop production tools – from agronomic service, to product choice, to our research that fuels future innovation. The proof is in the yield. Get the #YieldHero data at yieldhero.pioneer.com NEVER STOP GROWING. Visit us at corteva.ca ®, ™ Trademarks of Dow AgroSciences, DuPont or Pioneer and affiliated companies or their respective owners. © 2019 CORTEVA PIONEER® brand products are provided subject to the terms and conditions of purchase which are part of the labelling and purchase documents. 521713-070_PioneerWest_NSG_Brand_ExtraEndAnnual_8x10.75_092719_Ex_v1.inddCC20_AD.indd 1 1 2019-10-302019-09-27 3:58 3:02 PM PM THE OFFICIAL PUBLICATION OF THE SEASON OF CHAMPIONS Editor Laurie Payne Managing editor MESSAGES OF WELCOME 5 A GRATEFUL CHAMPION GIVES BACK 29 Al Cameron B.C.’s Tyler Tardi hopes to inspire HOST COMMITTEE 9 young curlers both on and off the ice Art director Samantha Edwards 2018 HOME HARDWARE CANADA CUP 10 Jennifer Jones and Brad Jacobs Production director win one of curling’s toughest events Marylou Morris Printer Sunview Press Cover photography 2018 Home Hardware Canada Cup champions Team Jones and Team Jacobs by Michael Burns Photography Photography Michael Burns Photography Scotties Tournament of Hearts photography Andrew Klaver BOTTCHER’S HOT STREAKS LEAD TO IMPRESSIVE RESULTS 30 Manager, national sponsorship Remarkable season leads to No. -

2019-20 Media Guide & Directory

2019-20 USA C U RLING M EDI A G U IDE & D IRE C TORY 2019-20 MEDIA GUIDE & CLUB DIRECTORY ROCK IT AT CROOKED PINT. Nothing matches curling like the lucys, burgers, tacos, and other incredible pub fair (not to mention craft brews and a full bar) at Crooked Pint. And remember, it’s okay to cheer with your mouth full! 3210 Chaska Boulevard • Chaska • crookedpint.com 952-361-6794 Table of Contents MEDIA GUIDE 02–86 ABOUT THE USCA 02 NATIONAL OFFICE STAFF 02 HIGH PERFORMANCE PROGRAM STAFF 03 BOARD OF DIRECTORS & BOARD LEADERSHIP 04 ATHLETES’ ADVISORY COUNCIL 04 SPONSORS AND PARTNERS 05 AFFILIATED ORGANIZATIONS 06 PAST PRESIDENTS/CHAIRPERSONS 07 HALL OF FAME & WORLD CURLING HALL OF FAME 08–09 WHAT IS CURLING? & ABCS OF CURLING 10–11 CURLING EQUIPMENT 12 WHO CURLS, AND WHERE? 13 GLOSSARY OF CURLING TERMS 14 CURLING’S OLYMPIC & PARALYMPIC HISTORY 15–17 U18 NATIONAL CHAMPIONSHIPS 18–21 COLLEGE NATIONAL CHAMPIONSHIP 22–23 MIXED DOUBLES NATIONAL & WORLD CHAMPIONSHIP 24–27 JUNIOR NATIONAL & JR. WORLD CHAMPIONSHIPS 28–41 SENIOR NATIONAL & SR. WORLD CHAMPIONSHIPS 42–51 CLUB NATIONAL CHAMPIONSHIPS 52–55 MIXED NATIONAL & WORLD CHAMPIONSHIP 56–61 ARENA NATIONAL CHAMPIONSHIPS 62–65 NATIONAL CHAMPIONSHIPS & WORLD CHAMPIONSHIPS 66–79 AWARDS 80–81, 86, 142–143 CURLING WORLD CUP 82 CONTINENTAL CUP 83 PROGRAMS & RESOURCES FOR CLUBS 84–85 DIRECTORY OF MEMBER ASSOCIATIONS 87–140 CLUBS AT LARGE 88 ALASKA CURLING ASSOCIATION 88–89 COLORADO CURLING ASSOCIATION 89 DAKOTA TERRITORY CURLING ASSOCIATION 89–93 GRAND NATIONAL CURLING CLUB 93–109 GREAT LAKES CURLING ASSOCIATION 109–113 MID-AMERICA CURLING ASSOCIATION 114–117 MIDWEST CURLING ASSOCIATION 117–118 MINNESOTA CURLING ASSOCIATION 119–126 MOUNTAIN PACIFIC CURLING ASSOCIATION 126–130 WASHINGTON CURLING ASSOCIATION 131 WISCONSIN CURLING ASSOCIATION 132–140 GRANITE SOCIETY 140 CHRIS MOORE LEGACY FUND 141 EVENTS 144 CREDITS: The USA Curling Media Guide & Directory is an annual publication of the USA Curling Communications Department. -

Filling up the House: Building an Appraisal Strategy for Curling Archives in Manitoba

FILLING UP THE HOUSE: BUILDING AN APPRAISAL STRATEGY FOR CURLING ARCHIVES IN MANITOBA by Allan Neyedly A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies of The University of Manitoba in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of MASTER OF ARTS Joint Master’s Program Department of History (Archival Studies) University of Manitoba / University of Winnipeg Winnipeg, Manitoba Copyright © 2011 by Allan Neyedly Abstract Curling is an important part of the Canadian cultural landscape, and nowhere is this more evident than in Manitoba. However, the documentation of curling records within archival repositories in the province has occurred without a strategic plan. This thesis first explores the modern archival appraisal theories and then proposes an appraisal model that utilizes a combination of the documentation strategy and macroappraisal in order to develop a strategy for the documentation of curling in Manitoba. Using this model, this thesis first examines the historical and contemporary context of Canadian sport in order to determine curling’s place within it, and then identifies five key functions of curling in order to evaluate, using function-based appraisal methodologies, the quality of the records that have been collected in archival repositories. The functions, structures, and records of two urban curling clubs and one rural curling club in Manitoba are then examined as case studies, and an appraisal strategy is suggested in order to better ensure that the records documenting curling in Manitoba are preserved. This strategy can be used as a template not only for appraising the records of curling, but for all sports. i Acknowledgements My class work in the University of Manitoba’s archival studies programme allowed me to quickly get a full-time position in my field, even without the completion of this thesis.