Rethinking Jeanne and the Theme of the Supernatural

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Eric Kurlander. Hitler's Monsters

130 Book Reviews / Correspondences 5 (2017) 113–139 Eric Kurlander. Hitler’s Monsters: A Supernatural History of the Third Reich. New Haven/London: Yale University Press, 2017. ISBN: 9780300189452. Among the steady stream of publications devoted to the relationship between esotericism and National Socialism, Eric Kurlander’s study is one of the rare examples of a serious contribution to an old debate. It offers a most welcome critical perspective that sets it apart from the scholarship of recent decades, most significantly Nicholas Goodrick-Clarke’s The Occult Roots of Nazism (1985) and Corinna Treitel’s A Science for the Soul (2004). In contrast to these studies, which were highly cautious about claiming actual links between esotericism and National Socialism, Kurlander establishes the central argument that “ National Socialism, even when critical of occultism, was more preoccupied by and indebted to a wide array of supernatural doctrines and esoteric practices than any mass political movement of the interwar period.” (xiv) By covering a vast spectrum of topics and sources, and by taking into consideration an impressive amount of secondary literature, the ambitions of Hitler’s Monsters are high: In the three chapters of Part One, Kurlander investigates the emergence of National Socialism since the late 1880s and its relationship to what is termed “the supernatural”; Part Two, again consisting of three chapters, discusses the relationship between the National Socialist state and the supernatural; while the last three chapters of Part Three deal with the period of the Second World War until 1945. Despite a range of important arguments and inspiring thoughts, Hitler’s Monsters is at times a highly problematic book that leaves an ambivalent impression. -

Ragnarok Worksheet

Ragnarok 231 RAGNAROK Also known as “the Twilight of the Gods,” Ragnarok, the Norse Doomsday, is the ultimate battle between good and evil—an event similar to the apocalypse of the Bible. According to the Norse myths, Ragnarok will contain a number of specific events, which are related here. But is it the end of the world—or just the beginning of a new one? hat tidings are to be told of Ragnarok? First, there W will come a winter called the Fimbul‐winter, where snow will drive from all quarters, the frost will be so severe, and the winds so keen and piercing that there will be no joy to be found— not even in the sun. There will be three such winters in succession without any intervening summer. Great wars will rage over all the world. Brothers will slay each other for the sake of gain, and no one will spare his father or mother in that carnage. Then a great supernatural tragedy will happen: The two wolves of darkness that have pursued the sun and moon since the beginning of time will finally catch their prey. One wolf will devour the sun, and the second wolf will devour the moon. The stars shall be hurled from heaven. Then it shall come to pass that the earth and the mountains will shake so violently that trees will be torn up by the roots, the mountains will topple down, and all bonds and fetters will be broken and snapped. Loki and the Fenrir‐wolf will be loosed. The sea will rush over the earth, for the Midgard Serpent will writhe in rage and seek to gain the land. -

Dr. Eric Kurlander Professor of Modern European History Stetson University

Dr. Eric Kurlander Professor of Modern European History Stetson University Department of History Office: (386) 822-7578 Elizabeth Hall, Unit 8344 (386) 822-7535 421 N. Woodland Blvd. Fax: (386) 822-7544 Stetson University Email: [email protected] Deland, FL 32724 EDUCATION HARVARD UNIVERSITY Cambridge, MA PhD, Modern European History. 2001 MA, Modern European History. 1997 BOWDOIN COLLEGE Brunswick, ME BA, summa cum laude. History and English (minor). 1994 PROFESSIONAL EXPERIENCE Professor, History Department, Stetson University Spring 2015 - present Professor and Chair, History Department, Stetson University Fall 2013 – Fall 2014 Associate Professor and Chair, History Department, Stetson University Fall 2010 – Spring 2013 Visiting Professor and Fulbright Fellow, History Department, Freiburg Pädagogische Hochschule January 2012 – July 2012 Associate Professor, History Department, Stetson University Fall 2007 – Spring 2010 Alexander von Humboldt Fellow, History Department, University of Bonn/Berlin December 2007 – June 2008 Thyssen-Heideking Fellow, Anglo-American Institute, University of Cologne June 2007 – February 2008 Assistant Professor, History Department, Stetson University Fall 2001 – Spring 2007 Assistant Senior Tutor, Currier House, Harvard University Fall 2000 – Spring 2001 Teaching Fellow, History Department, Harvard University Fall 1999 – Spring 2001 SELECTED PUBLICATIONS (2001 – present) Books Hitler’s Monsters: A Supernatural History of the Third Reich. New Haven and London: Yale University Press (under contract). The West in Question: Continuity and Change. v. II. New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press (under contract) Monica Black and Eric Kurlander, eds., Revisiting the Nazi Occult: Histories, Realities, Legacies. Rochester: Camden House, 2015. Joanne Miyang Cho, Eric Kurlander, and Douglas McGetchin, eds., Transcultural Encounters between Germany and India: Kindred Spirits in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries, New York and London: Routledge, 2014. -

The Supernatural World of the Kawaiisu by Maurice Zigmond1

The Supernatural World of the Kawaiisu by Maurice Zigmond1 The most obvious characteristic at the supernatural world of the Kawaiisu is its complexity, which stands in striking contrast to the “simplicity” of the mundane world. Situated on and around the southern end of the Sierra Nevada mountains in south - - central California, the tribe is marginal to both the Great Basin and California culture areas and would probably have been susceptible to the opprobrious nineteenth century term, ‘Diggers’ Yet, if its material culture could be described as “primitive,” ideas about the realm of the unseen were intricate and, in a sense, sophisticated. For the Kawaiisu the invisible domain is tilled with identifiable beings and anonymous non-beings, with people who are half spirits, with mythical giant creatures and great sky images, with “men” and “animals” who are localized in association with natural formations, with dreams, visions, omens, and signs. There is a land of the dead known to have been visited by a few living individuals, and a netherworld which is apparently the abode of the spirits of animals - - at least of some animals animals - - and visited by a man seeking a cure. Depending upon one’s definition, there are apparently four types of shamanism - - and a questionable fifth. In recording this maze of supernatural phenomena over a period of years, one ought not be surprised to find the data both inconsistent and contradictory. By their very nature happenings governed by extraterrestrial fortes cannot be portrayed in clear and precise terms. To those involved, however, the situation presents no problem. Since anything may occur in the unseen world which surrounds us, an attempt at logical explanation is irrelevant. -

Will This Manhattan Projects Original Artwork Cliffhanger Make Another

COMICS COSPLAY TV/FILM GAMES SUBMIT CGC Search … Will This Manhattan Projects Original Artwork Cliffhanger Make Another Big Splash? Posted by Mark Seifert March 19, 2014 0 Comments Facebook Twitter Pinterest LinkedIn Tumblr Email Reddit [The Manhattan Projects #18 has been out for a couple weeks, but still — if you haven’t read this issue and plan to, you might want to skip this post for now.] Several years into the digital era for both comics reading and comics production, I still love to look at original comic art up close. The look and feel of the art board, the subtle texture of the ink, the faint traces of changes and corrections… it all adds up to a little extra insight into the time and circumstances behind the comics book’s creation. We’ve mentioned a bunch of noteworthy original art sales here in recent times — from that awe-inspiring Golden Age Action Comics #15 cover by Fred Guardineer, to this Silver Age Fantastic Four #55 page by Jack Kirby, to this Bronze Age classic Amazing Spider- Man #121 cover by John Romita Sr, down to the current record holder for a piece of American comic book art with this Amazing Spider-Man #328 cover by Todd McFarlane. And increasingly, original art sales from much more recent comics are turning heads as well. It’s probably no surprise that Skottie Young original art is highly sought after, or that Walking Dead original art — even panel pages — can command some eye- popping prices. But modern comic art collectors have broadened their interests to many other artists and titles of quality in recent times, such as this Pia Guerra Y: The Last Man panel page that recently went for $1000. -

ABSTRACT the Women of Supernatural: More Than

ABSTRACT The Women of Supernatural: More than Stereotypes Miranda B. Leddy, M.A. Mentor: Mia Moody-Ramirez, Ph.D. This critical discourse analysis of the American horror television show, Supernatural, uses a gender perspective to assess the stereotypes and female characters in the popular series. As part of this study 34 episodes of Supernatural and 19 female characters were analyzed. Findings indicate that while the target audience for Supernatural is women, the show tends to portray them in traditional, feminine, and horror genre stereotypes. The purpose of this thesis is twofold: 1) to provide a description of the types of female characters prevalent in the early seasons of Supernatural including mother-figures, victims, and monsters, and 2) to describe the changes that take place in the later seasons when the female characters no longer fit into feminine or horror stereotypes. Findings indicate that female characters of Supernatural have evolved throughout the seasons of the show and are more than just background characters in need of rescue. These findings are important because they illustrate that representations of women in television are not always based on stereotypes, and that the horror genre is evolving and beginning to depict strong female characters that are brave, intellectual leaders instead of victims being rescued by men. The female audience will be exposed to a more accurate portrayal of women to which they can relate and be inspired. Copyright © 2014 by Miranda B. Leddy All rights reserved TABLE OF CONTENTS Tables -

“Who's SS-Scared?” to “Zoinks!”: Scooby Doo and the Embracement

From “Who’s S-S-Scared?” to “Zoinks!”: Scooby Doo and the Embracement of Technology through the Rejection of the Supernatural Saturday mornings of my childhood always included the cartoon Scooby Doo, which premiered in September of 1969. Requested by Fred Silverman, the head of daytime programming at CBS, Scooby Doo was meant to be a high school version The Many Loves of Dobie Gillis, with the addition that the characters played in a band together and solved mysteries. There was to be a horror feel about the show, since Silverman was a huge fan of horror films. William Hanna and Joseph Barbara’s writers’ first attempt was a literally version of Silverman’s request: A band consisting of five members who solver crimes between gigs, and their dog Too Much. After revision, the show, titled Who’s S-S-Scared?, was rejected by CBS executives for being too scary. It was rejected a second time for being too boring. The final version was based on the dog character, bring comedy into contrast with the “scary,” and Silverman suggested the name of the new dog star be the scat line from Frank Sinatra’s “Strangers in the Night”, “doo-be-doo-be-doo.” Scooby Doo had its beginnings, crushing its competition when it premiered, and 48 years later, it’s still going strong. In this paper, I explore one reason for the cartoon’s success. I argue that through Scooby Doo, Hanna- Barbara and later Warner Bros, are exploring the same fears of industrial revolution – including technical and digital revolution - that Mary Shelley explored in Frankenstein. -

Theology of Supernatural

religions Article Theology of Supernatural Pavel Nosachev School of Philosophy and Cultural Studies, HSE University, 101000 Moscow, Russia; [email protected] Received: 15 October 2020; Accepted: 1 December 2020; Published: 4 December 2020 Abstract: The main research issues of the article are the determination of the genesis of theology created in Supernatural and the understanding of ways in which this show transforms a traditional Christian theological narrative. The methodological framework of the article, on the one hand, is the theory of the occulture (C. Partridge), and on the other, the narrative theory proposed in U. Eco’s semiotic model. C. Partridge successfully described modern religious popular culture as a coexistence of abstract Eastern good (the idea of the transcendent Absolute, self-spirituality) and Western personified evil. The ideal confirmation of this thesis is Supernatural, since it was the bricolage game with images of Christian evil that became the cornerstone of its popularity. In the 15 seasons of its existence, Supernatural, conceived as a story of two evil-hunting brothers wrapped in a collection of urban legends, has turned into a global panorama of world demonology while touching on the nature of evil, the world order, theodicy, the image of God, etc. In fact, this show creates a new demonology, angelology, and eschatology. The article states that the narrative topics of Supernatural are based on two themes, i.e., the theology of the spiritual war of the third wave of charismatic Protestantism and the occult outlooks derived from Emmanuel Swedenborg’s system. The main topic of this article is the role of monotheistic mythology in Supernatural. -

Supernatural' Fandom As a Religion

Claremont Colleges Scholarship @ Claremont CMC Senior Theses CMC Student Scholarship 2019 The Winchester Gospel: The 'Supernatural' Fandom as a Religion Hannah Grobisen Claremont McKenna College Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.claremont.edu/cmc_theses Part of the Film and Media Studies Commons Recommended Citation Grobisen, Hannah, "The Winchester Gospel: The 'Supernatural' Fandom as a Religion" (2019). CMC Senior Theses. 2010. https://scholarship.claremont.edu/cmc_theses/2010 This Open Access Senior Thesis is brought to you by Scholarship@Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in this collection by an authorized administrator. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Claremont McKenna College The Winchester Gospel The Supernatural Fandom as a Religion submitted to Professor Elizabeth Affuso and Professor Thomas Connelly by Hannah Grobisen for Senior Thesis Fall 2018 December 10, 2018 Table of Contents Dad’s on a Hunting Trip and He Hasn’t Been Home in a Few Days: My Introduction to Supernatural and the SPN Family………………………………………………………1 Saving People, Hunting Things. The Family Business: Messages, Values and Character Relationships that Foster a Community……………………………………………........9 There is No Singing in Supernatural: Fanfic, Fan Art and Fan Interpretation….......... 20 Gay Love Can Pierce Through the Veil of Death: The Importance of Slash Fiction….25 There’s Nothing More Dangerous than Some A-hole Who Thinks He’s on a Holy Mission: Toxic Misrepresentations of Fandom……………………………………......34 This is the End of All Things: Final Thoughts………………………………………...38 Works Cited……………………………………………………………………………39 Important Characters List……………………………………………………………...41 Popular Ships…………………………………………………………………………..44 1 Dad’s on a Hunting Trip and He Hasn’t Been Home in a Few Days: My Introduction to Supernatural and the SPN Family Supernatural (WB/CW Network, 2005-) is the longest running continuous science fiction television show in America. -

Characterization in the Operas of Penderecki Karekterizacija V Operah Pendereckega

N. O’LOUGHLIN • CHARACTERIZATION IN THE OPERAS ... UDK 782.07Penderecki DOI: 10.4312/mz.51.1.127-137 Niall O’Loughlin Univerza v Loughboroughu Loughborough University Characterization in the Operas of Penderecki Karekterizacija v operah Pendereckega Prejeto: 8. januar 2015 Received: 8th January 2015 Sprejeto: 31. marec 2015 Accepted: 31st March 2015 Ključne besede: Penderecki, opera, karakterizacija, Keywords: Penderecki, opera, characterization, Huxley, Whiting, Milton, Hauptmann, Jarry Huxley, Whiting, Milton, Hauptmann, Jarry IZVLEČEK ABSTRACT Karakterizacija v štirih operah Pendereckega je Characterization in the four operas of Krzystof dobro razvita. Vključuje specifične melodične in- Penderecki is well developed. It includes specified tervale za junake, popačene vokalne linije, uporabo melodic intervals for characters, distorted vocal koloraturnega petja in različne oblike cerkvenega lines, the use of coloratura singing and various petja ter govorjenja. forms of chanting and speaking. Introduction Characterization in dramatic works is a complicated issue. In the first instance it concerns the words chosen and what form of emphasis has been adopted by the writ- er. The sequence of events in a drama will also have much to do with how the character is allowed to develop, and in particular how each character responds to the new situ- ations that arise. In addition, the actual performance by the actors in a spoken drama can add a new dimension to the definition of the character in a spoken play. When making the transfer to an operatic scenario, the words obviously are still of the first importance, but now the way that the words are set to music (if at all) and the level at which the words can be understood by the audience are now particularly relevant. -

DVD Press Release

DVD press release The Devils 2-Disc Special Edition A film by Ken Russell Vanessa Redgrave, Oliver Reed Forty years ago, The Devils caused outrage amongst audiences and critics after one of the longest-running battles with the BBFC was resolved and the film finally opened in cinemas. Now recognised as a landmark in British film history, The Devils finally gets its DVD premiere on 19 March, released by the BFI in the original UK X certificate version with a wealth of new and exciting extra features and a 44-page illustrated booklet. The death of director Ken Russell, in November last year, sparked an outpouring of tributes from both the film industry and fans. This 2-disc Special Edition release of what many consider to be his greatest work is a justly fitting tribute to one of Britain’s true mavericks. The Devils is based on John Whiting’s stage play and Aldous Huxley’s novel. In 17th century France, a promiscuous and divisive local priest, Urbain Grandier (Oliver Reed), uses his powers to protect the city of Loudun from destruction by the establishment. Soon, he stands accused of the demonic possession of Sister Jeanne (Vanessa Redgrave), whose erotic obsession with him fuels the hysterical fervour that sweeps through the convent. With Ken Russell’s bold and brilliant direction, magnificent performances by Oliver Reed and Vanessa Redgrave, exquisite Derek Jarman sets and a sublimely dissonant score by Sir Peter Maxwell Davies, The Devils stands as a profound and sincere commentary on religious hysteria, political persecution and the corrupt marriage of church and state. -

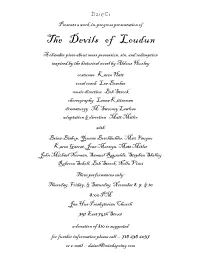

The Devils of Loudun

DzieCi Presents a work-in-progress presentation of The Devils of Loudun A chamber piece about mass possession, sin, and redemption inspired by the historical novel by Aldous Huxley costumes Karen Hatt vocal coach Lea Bracher music direction Bob Strock choreography Lenna Kitterman dramaturgy M. Sweeney Lawless adaptation & direction Matt Mitler with Brina Bishop, Yvonne Brechbuhler, Max Faugno Karen Garrat, Joan Merwyn, Matt Mitler John Michael Norman, Samuel Reynolds, Stephen Shelley Rebecca Sokoll, Bob Strock, Nella Vinci Three performances only: Thursday, Friday, & Saturday, November 8, 9, & 10 8:00 PM Jan Hus Presbyterian Church 351 East 74th Street a donation of $10 is suggested for further information please call -- 718 638 6037 or e-mail -- [email protected] Long is the way and hard, that out of Hell leads up to Light. Milton, Paradise Lost A Note on the Production The international experimental theatre company, DZIECI, has been working diligently but quietly. For almost five years now, an intense effort has been made to train each member and develop a tightly knit ensemble while exploring an organic process toward creativity and personal growth. Towards this aim, DZIECI balances its work on performance with work of service through creative and therapeutic interactions with patients in a variety of institutional settings. Since its inception, DZIECI has been involved in an open-ended process of adapting and rehearsing Aldous Huxley's historical treatise, The Devils of Loudun. The story centers around a group of 17th century Ursuline nuns who, inspired by their Prioress, Sister Jeanne des Anges, became officially "possessed" and were forced to undergo public exorcisms.