UK Policy on Space.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download the 2014 ASDC National Conference Delegate List As

Organisation Delegate ASDC Dr Penny Fidler ASDC Dr Michaela Livingstone ASDC Maddy Foard A D Hunt Ltd Dr Anne Hunt Aardman Animations Heather Wright Aardman Animations Ian Haynes Amgueddfa Cymru - National Museum Wales Liam Doyle Anglian Water Marcia Davies Anglian Water Ellie Henderson Arts Council England Laura Gander-Howe At-Bristol Science Centre Phil Winfield At-Bristol Science Centre Bonnie Buckley At-Bristol Science Centre Dan Bird At-Bristol Science Centre Jo Bryant At-Bristol Science Centre Dr Kathy Fawcett At-Bristol Science Centre John Polatch At-Bristol Science Centre Raj Bista Babraham Institute Linden Fradet BBC Science Helen Thomas BBSRC Rebecca Kerby Ben Gammon Consulting Dr Ben Gammon BIG - STEM Communicators Network James Piercy Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery Dr Kenny Webster BIS Susannah Wiltshire Blenheim Accounting Chris Godden Blenheim Accounting Gill Godden BIS Chris Shipley BP Ian Duffy British Science Association Dr Christina Fuentes Tibbitt Cambridge Science Centre Rosemary Ansell Cambridge Science Centre Gaetan Lee Cancer Research UK Kirsteen Campbell Catalyst Science Discovery Centre Dr Diana Leitch Centre of the Cell Umme Aysha CERN@school Clare Harvey CERN@school Dr Tom Whyntie Daredevil Labs / Wellcome Trust Greg Foot Dundee Science Centre Linda Leuchars Dundee Science Centre Louise Smith Dundee Science Centre Rebecca Erskine Eden Project Gordon Seabright Eden Project Gabriella Gilkes Eureka! The National Children's Museum Leigh-Anne Stradeski EXplora Science, Technology and Discovery Centre Caroline Galpin -

Classroom Physics June 2014 Edition

ClassroomThe newsletter for affiliated schools physicsJune 2014 Issue 29 Teacher support IOP successfully wins extension to Stimulating Physics Network support The Institute, in partnership with Myscience, IOP has been awarded a new contract by the Department for Education to run the Stimulating Physics Network (SPN) until March 2016. The SPN is an important national programme supporting the teaching and learning of physics in schools across England; this contract ensures that the SPN free, open CPD workshops for teachers in will continue operating for at least another the SLP’s associated schools and the local two years, which is an endorsement of the area. These activities will complement and success and impact that has been achieved support the SLP and its wider objectives, by the programme to date. and will form a national programme of physics CPD that is available to all teachers Celebrating success in England. Since 2012, the Institute’s SPN has facilitated more than 80,000 teacher hours Expansion to counter stereotyping of physics CPD and more than 60,000 Over the next two years, the SPN will pupils have experienced SPN engagement also be running a new pilot project called activities. The SPN is based around a team of Improving Gender Balance (IGB). A team 35 teaching and learning coaches (TLCs) who of specialist project officers will work are all highly experienced and successful intensively with 20 schools for two years, to physics teachers; each TLC providing support identify and resolve the issues surrounding to 12 SPN Partner Schools. the disproportionately low number of The aim of the SPN is to improve pupils’ A teacher attending a “Fun is Physics” session at girls studying A-level physics, including experience of physics at Key Stage 3 and a Stimulating Physics Network Summer School girls’ confidence and resilience, teachers’ 4, as measured by an increase in the (four-day residential CPD courses held at Oxford, classroom practice, and whole-school number of pupils choosing to study A-level Cambridge and York each year). -

National Space Centre Exhibition and Research Complex

National Space Centre Exhibition and Research Complex The Basics Location: Exploration Drive, Leicester, LE4 5NS, Leicestershire, England Latitude/Longitude: 52°39'13"N, 01°07'57"W; altitude: 185' Building Type: Space Museum and Research Facility Annual Precipitaion: 606.2mm (23.9") Square Footage/Stories: 7,600 m2 (81,806 ft2)/tower 41 m (135') high Completion: Jun 2001 Client: National Space Centre Property Company Photo Credit: Philip Jordan Design Team: Grimshaw Architects Structural and Services Engineer: ARUP Background and Context In 1996, Nicholas Grimshaw and Partners won a national competition to design the National Space Science Centre, a Millenium Project for the East Midlands. Millenium Projects are community enrichment tasks selected by the Millenium Commission and funded by the UK National Lottery. The commission is an independent group yet under the oversight of the government. Their intent was to assist these communities in marking the transition from the second millenium to the third. Leicester is located in the Midlands of England, north of London by about 100 miles. Like many English cities, Leicester’s growth exploded during the Industrial Revolution. The Soar Canal allowed coal and iron to be easily shipped into town, spurring the growth. By the beginning of the 20th Century, Leicester had established itself as a hub of engineering. The College of Art and Technology opened in 1897, and transformed into Leices- ter Polytechnic in 1969, and then the University of Leicester in 1992. It is then obviously appropriate that a Photo Credit: Philip Jordan Centre dedicated to scientific and engineering advacement be located in a city whose history is so tied to these endevours. -

The United Kingdom's Civil Space Activities

House of Commons Committee of Public Accounts The United Kingdom's civil space activities Twenty–first Report of Session 2004–05 Report, together with formal minutes, oral and written evidence Ordered by The House of Commons to be printed 6 April 2005 HC 47 Published on 9 June 2005 by authority of the House of Commons London: The Stationery Office Limited £11.00 The Committee of Public Accounts The Committee of Public Accounts is appointed by the House of Commons to examine “the accounts showing the appropriation of the sums granted by Parliament to meet the public expenditure, and of such other accounts laid before Parliament as the committee may think fit” (Standing Order No 148). Membership Mr Edward Leigh MP (Conservative, Gainsborough) (Chairman) Mr Richard Allan MP (Liberal Democrat, Sheffield Hallam) Mr Richard Bacon MP (Conservative, South Norfolk) Mrs Angela Browning MP (Conservative, Tiverton and Honiton) Jon Cruddas MP (Labour, Dagenham) Rt Hon David Curry MP (Conservative, Skipton and Ripon) Mr Ian Davidson MP (Labour, Glasgow Pollock) Rt Hon Frank Field MP (Labour, Birkenhead) Mr Brian Jenkins MP (Labour, Tamworth) Mr Nigel Jones MP (Liberal Democrat, Cheltenham) Jim Sheridan MP (Labour, West Renfrewshire) Mr Siôn Simon MP (Labour, Birmingham Erdington) Mr Gerry Steinberg MP (Labour, City of Durham) Mr Stephen Timms MP (Labour, East Ham) Jon Trickett MP (Labour, Hemsworth) Rt Hon Alan Williams MP (Labour, Swansea West) Powers Powers of the Committee of Public Accounts are set out in House of Commons Standing Orders, principally in SO No 148. These are available on the Internet via www.parliament.uk. -

Space and Satellites

House of Commons Science and Technology Select Committee inquiry on Space and Satellites Response to the inquiry, 29 January 2016 This evidence is submitted by the Royal Academy of Engineering. As the UK’s national academy for engineering, we bring together the most successful and talented engineers from across the engineering sectors for a shared purpose: to advance and promote excellence in engineering. The views described in this response were assembled through consultation with our Fellows. These include experts in space engineering from industry and academia. Introduction 1. Since the publication of the UK Space Innovation and Growth Strategy 2014-2030, the government has picked up many of the recommendations, which has galvanised the industry. The success of the strategy is illustrated by the high annual growth figure of 7.3%1 reported in 2014. Furthermore, this is a high-productivity industry whose expansion aligns well with the objectives of the government’s Productivity Plan and which is well placed to capitalise on the UK’s strengths in IT, the digital economy and finance for investment. 2. Overseas companies perceive the UK as a good place to locate their business and inward investment is happening. This positive perception is a direct result of the UK’s clear long- term strategy, the creation of the UK Space Agency, European Space Agency (ESA) investment to establish a presence in the UK, the broader business environment, a strong technology base and the availability of entrepreneurial and highly-skilled people to employ. 3. The Academy welcomes government’s continuing support represented by the recent National Space Policy and recognition of the cross-cutting nature of space across a huge range of government departments and agencies. -

Pioneer Park, Leicester

PIONEER PARK, Draft, June 2018 LEICESTER INTRODUCTORY BRIEF August 2018 PIONEER PARK - DEVELOPMENT BRIEF 1.0 INTRODUCTION 1.1 Pioneer Park Pioneer Park is identified within the Mayor’s Economic Action strategic objectives for Pioneer Park. Plan - 2016-2020 as a priority project for Leicester. It is the objective of City Council to see Pioneer Park developed The two sites are located on Exploration Drive, which with a mixture of new workspaces for sale and lease that connects Abbey Lane (A6) to the National Space Centre. can accommodate innovative knowledge-based technology The sites are approximately 1.2 miles from Leicester businesses. city centre. The sites are separated from each other by Exploration Drive. The Site A is situated immediately to the The Pioneer Park is covered by a strategic masterplan which north of the successful Dock 1 building and covers an area sets out how the area covered by this Brief, and adjoining of approximately 1.008 acres. Site B is located to the west locations, might be developed to create a coherent specialist of Dock 1 and covers an area of approximately 2.93 acres. business cluster. In addition Leicester is committed to taking Both sites are roughly level with good access, frontage and forward; work space development, accessibility and public visibility. realm projects which fall within the Pioneer Park area. The Council is now seeking a developer with the skills and These include the Dock 1 building, which was partially ERDF experience necessary to bring forward the development of the funded, opened in autumn 2013 and now accommodates two sites. -

ANDREW LAWRENCE Regius Professor of Astronomy, University

ANDREW LAWRENCE Regius Professor of Astronomy, University of Edinburgh Institute for Astronomy Royal Observatory Edinburgh The IfA is part of the University's School of Physics and Astronomy and co-located with STFC's UK Astronomy Technology Centre Brief Resumeé Born Margate, Kent, England April 23rd 1954. Schools Drapers Mills Infants and Juniors, Margate, Kent Chatham House Grammar School, Ramsgate, Kent 1972-76 Dept of Astronomy, University of Edinburgh BSc Astrophysics 1976-80 Dept of Physics, University of Leicester PhD in X-ray Astronomy 1980-81 Centre for Space Research, Massachusetts Institute of Technology Exchange Scientist 1981-84 Royal Greenwich Observatory Senior Research Fellow 1984-87 School of Mathematical Sciences, Queen Mary College, Univ. London SERC PDRA 1987-89 School of Mathematical Sciences, Queen Mary College, Univ. London SERC Advanced Fellow 1989-94 Dept of Physics, Queen Mary and Westfield College, Univ. London Lecturer 1994 - Institute for Astronomy, Univ. Edinburgh Regius Professor of Astronomy 1994-03 Head of Institute for Astronomy, University of Edinburgh 2003-08 Head of School of Physics, Univ. Edinburgh 2008-09 Visiting Scientist, Kavli Institute for Particle Astrophysics and Cosmology (KIPAC), Univ. Stanford 2009- Affiliate member, KIPAC, Univ. Stanford Research Interests • Observational cosmology (large scale structure, galaxy formation, high-redshift galaxies) • Active galaxies and quasars (spectral energy distribution, unified schemes, variability, obscured quasars) • Survey Astronomy (leading a new -

Open PDF 424KB

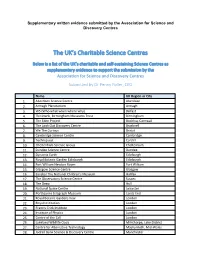

Supplementary written evidence submitted by the Association for Science and Discovery Centres The UK’s Charitable Science Centres Below is a list of the UK’s charitable and self-sustaining Science Centres as supplementary evidence to support the submission by the Association for Science and Discovery Centres Submitted by Dr Penny Fidler, CEO Name UK Region or City 1. Aberdeen Science Centre Aberdeen 2. Armagh Planetarium Armagh 3. W5 (Who what when where why) Belfast 4. Thinktank, Birmingham Museums Trust Birmingham 5. The Eden Project Bodelva, Cornwall 6. The Look Out Discovery Centre Bracknell 7. We The Curious Bristol 8. Cambridge Science Centre Cambridge 9. Techniquest Cardiff 10. Cheltenham Science Group Cheltenham 11. Dundee Science Centre Dundee 12. Dynamic Earth Edinburgh 13. Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh Edinburgh 14. Fort William Newton Room Fort William 15. Glasgow Science Centre Glasgow 16. Eureka! The National Children's Museum Halifax 17. The Observatory Science Centre Sussex 18. The Deep Hull 19. National Space Centre Leicester 20. Porthcurno telegraph Museum Lands End 21. Royal Botanic Gardens Kew London 22. Royal Institution London 23. Francis Crick Institute London 24. Institute of Physics London 25. Centre of the Cell London 26. Lakeland Wildlife Oasis Milnthorpe, Lake District 27. Centre for Alternative Technology Machynlleth, Mid-Wales 28. Jodrell Bank Science & Discovery Centre Manchester 29. International Centre For Life Newcastle 30. Kielder Observatory Northumberland 31. Scottish Seabird Centre North Berwick 32. Oxford University Museum of Natural History Oxford 33. Science Oxford Oxford 34. National Marine Aquarium Plymouth 35. EXplora Science and Discovery Centre Poole 36. MAGNA Rotherham 37. -

RAS Annual Report & Financial Statements 2018

FINANCIAL REPORT Royal Astronomical Society Annual Report & Financial Statements 2018 ANNUAL REPORT AND FINANCIAL STATEMENTS 1 FINANCIAL REPORT Royal Astronomical Society Patron Senior Staff Her Majesty the Queen Executive Director: Philip Diamond Deputy Executive Director: Robert Massey Trustees The Council members who served during 2018 were: Registered and Principal Office Prof. John Zarnecki (President, G, until May 2018, Open University) Burlington House Piccadilly Prof. Mike Cruise (President, A, from May 2018, University of Birmingham) London Dr Megan Argo (Councillor, A, University of Central Lancaster) W1J 0BQ Dr Mandy Bailey (Secretary, A, Open University) Charity registration number Charles Barclay (Vice-President, A) 226545 Dr Nigel Berman (Treasurer, A) Prof. Mike Bode (Councillor, A, until May 2018, Liverpool John Moores University) Auditor Buzzacott LLP Prof. William Chaplin (Councillor, A, from May 2018, University of Birmingham) 130 Wood Street Prof. Ian Crawford (Vice-President, G, Birkbeck College) London Dr Paul Daniels (Councillor, A) EC2V 6DL Prof. Yvonne Elsworth (Vice-President, G, until May 2018, University of Birmingham) Bankers Prof. Lyndsay Fletcher (Senior Secretary, G, University of Glasgow) HSBC Bank plc Dr Claire Foullon (Councillor, A, from May 2018, University of Exeter) West End Corporate Banking Centre Prof. Brad Gibson (Councillor, A, until May 2018, University of Hull) 70 Pall Mall London Dr Stacey Habergham-Mawson (Vice-President, A, from May 2018, Liverpool John SW1Y 5EZ Moores University) Prof. Lorraine Hanlon (Councillor, A, from May 2018, University College Dublin) National Westminster Bank St James’ & Piccadilly Branch Dr Caitriona Jackman (Councillor, G, until May 2018, University of Southampton) PO Box 2 DG Kevin Kilburn (Councillor, A, from May 2018) 208 Piccadilly Prof. -

Evolution of the Role of Space Agencies

Full Report Evolution of the Role of Space Agencies Report: Title: “ESPI Report 70 - Evolution of the Role of Space Agencies - Full Report” Published: October 2019 ISSN: 2218-0931 (print) • 2076-6688 (online) Editor and publisher: European Space Policy Institute (ESPI) Schwarzenbergplatz 6 • 1030 Vienna • Austria Phone: +43 1 718 11 18 -0 E-Mail: [email protected] Website: www.espi.or.at Rights reserved - No part of this report may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or for any purpose without permission from ESPI. Citations and extracts to be published by other means are subject to mentioning “ESPI Report 70 - Evolution of the Role of Space Agencies - Full Report, October 2019. All rights reserved” and sample transmission to ESPI before publishing. ESPI is not responsible for any losses, injury or damage caused to any person or property (including under contract, by negligence, product liability or otherwise) whether they may be direct or indirect, special, incidental or consequential, resulting from the information contained in this publication. Design: copylot.at Cover page picture credit: NASA TABLE OF CONTENT 1 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................. 1 1.1 Background .......................................................................................................................................... 1 1.2 Rationale .............................................................................................................................................. -

UK Space Science: a Summary of the Research Community and Its Benefits

Source: ESA UK Space Science: a summary of the research community and its benefits Full Report for FINAL REPORT April 2021 Contents Executive Summary 4 Introduction 6 Scope 6 Methodology 7 Nature of the UK space science research base 9 Universities 9 University researchers 11 Non-university organisations, networks and researchers 14 Benefits from UK space science research 17 Benefits across the mission lifecycle 17 In-depth case study: the Gaia mission 27 Themes of benefit 29 Summary 34 Annex: list of consultees 35 2 About us know.space1 is a specialist space economics consultancy, based in London and Dublin. Founded by the leading sector experts, Greg Sadlier know. /nəʊ/v. and Will Lecky, it is motivated by a single mission: to be the source of authoritative economic knowledge for the space sector. to understand clearly and with certainty www.know.space [email protected] Acknowledgements We would like to thank Dr James Endicott and Professor Andrew Holland from SPAN / the Open University for their useful guidance and feedback over the course of the project. We would also like to thank all the interviewees consulted for their time, and for the range of interesting and enjoyable discussions. Responsibility for the content of this report remains with know.space. Images Cover and Header: ‘ESA: The Smile Mission’, ©ESA/ATG medialab. The Solar wind Magnetosphere Ionosphere Link Explorer, or SMILE, is a joint mission between the European Space Agency (ESA) and the Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS). SMILE aims to build a more complete understanding of the Sun-Earth connection by measuring the solar wind and its dynamic interaction with the magnetosphere and is due for launch in 2021. -

Polycom Video Conferencing Solutions Deliver Countown to Success in Schools National Space Centre

EMEA | Education | Video Polycom® in Education Polycom Video Conferencing Solutions Deliver Countown to Success in Schools National Space Centre Polycom video conferencing solutions help launch schools Challenge To deliver a unique, National Curriculum- on a mission to increase awareness and understanding of linked classroom learning experience for space and consequently foster a long-term interest in children all over the UK mathematics, science and technology. Solution A 1 1/2-hour video conference space programme Pupils around the country are experiencing the excitement of space exploration from the comfort of their own classrooms thanks to Polycom video conferencing technology installed at the National Space Result Centre in Leicester. Using a live interactive video link to “Mission Control” at the National Space A 1 1/2-hour video conference space programme Centre, teachers can engage pupils at Key Stage 2 and 3 (11 to 14 year olds) with a one and a half hour called “Operation Montserrat” that engages, interests and educates pupils in the classrooms curriculum-linked space programme called “Operation Montserrat” which is based on the real-life in all aspects of space exploration while eruption on the island of Montserrat in the Caribbean in 1996. Apart from experiencing the power of engendering an interest in maths, physics video conferencing technology, often for the first time, pupils also benefit from exercises in team and geography building, decision-making and logistics and gain the opportunity to apply their knowledge of geography, maths and physics. National Space Centre Education Manager, Chris Darby explains: “The National Space Centre was created to inspire and educate – a mission that remains at the core of everything we do today and in the future.