King Saul a Re-Examination Of.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Attitudes Towards Linguistic Diversity in the Hebrew Bible

Many Peoples of Obscure Speech and Difficult Language: Attitudes towards Linguistic Diversity in the Hebrew Bible The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Power, Cian Joseph. 2015. Many Peoples of Obscure Speech and Difficult Language: Attitudes towards Linguistic Diversity in the Hebrew Bible. Doctoral dissertation, Harvard University, Graduate School of Arts & Sciences. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:23845462 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA MANY PEOPLES OF OBSCURE SPEECH AND DIFFICULT LANGUAGE: ATTITUDES TOWARDS LINGUISTIC DIVERSITY IN THE HEBREW BIBLE A dissertation presented by Cian Joseph Power to The Department of Near Eastern Languages and Civilizations in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the subject of Near Eastern Languages and Civilizations Harvard University Cambridge, Massachusetts August 2015 © 2015 Cian Joseph Power All rights reserved. Dissertation Advisor: Professor Peter Machinist Cian Joseph Power MANY PEOPLES OF OBSCURE SPEECH AND DIFFICULT LANGUAGE: ATTITUDES TOWARDS LINGUISTIC DIVERSITY IN THE HEBREW BIBLE Abstract The subject of this dissertation is the awareness of linguistic diversity in the Hebrew Bible—that is, the recognition evident in certain biblical texts that the world’s languages differ from one another. Given the frequent role of language in conceptions of identity, the biblical authors’ reflections on language are important to examine. -

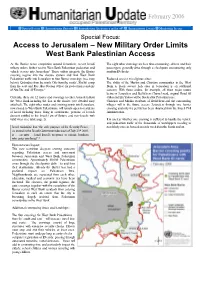

Access to Jerusalem – New Military Order Limits West Bank Palestinian Access

February 2006 Special Focus Humanitarian Reports Humanitarian Assistance in the oPt Humanitarian Events Monitoring Issues Special Focus: Access to Jerusalem – New Military Order Limits West Bank Palestinian Access As the Barrier nears completion around Jerusalem, recent Israeli The eight other crossings are less time-consuming - drivers and their military orders further restrict West Bank Palestinian pedestrian and passengers generally drive through a checkpoint encountering only vehicle access into Jerusalem.1 These orders integrate the Barrier random ID checks. crossing regime into the closure system and limit West Bank Palestinian traffic into Jerusalem to four Barrier crossings (see map Reduced access to religious sites: below): Qalandiya from the north, Gilo from the south2, Shu’fat camp The ability of the Muslim and Christian communities in the West from the east and Ras Abu Sbeitan (Olive) for pedestrian residents Bank to freely access holy sites in Jerusalem is an additional of Abu Dis, and Al ‘Eizariya.3 concern. With these orders, for example, all three major routes between Jerusalem and Bethlehem (Tunnel road, original Road 60 Currently, there are 12 routes and crossings to enter Jerusalem from (Gilo) and Ein Yalow) will be blocked for Palestinian use. the West Bank including the four in the Barrier (see detailed map Christian and Muslim residents of Bethlehem and the surrounding attached). The eight other routes and crossing points into Jerusalem, villages will in the future access Jerusalem through one barrier now closed to West Bank Palestinians, will remain open to residents crossing and only if a permit has been obtained from the Israeli Civil of Israel including those living in settlements, persons of Jewish Administration. -

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Piety, Practice, and Politics: Agency and Ritual in the Late Bronze Age Southern Levant Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/8vx8j9v5 Author DePietro, Dana Douglas Publication Date 2012 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Piety, Practice, and Politics: Ritual and Agency in the Late Bronze Age Southern Levant By Dana Douglas DePietro A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Near Eastern Studies in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Marian Feldman, Chair Professor Benjamin Porter Professor Aaron Brody Professor Margaret Conkey Spring 2012 © 2012- Dana Douglas DePietro All rights reserved. Abstract Piety, Practice, and Politics: Ritual and Agency in the Late Bronze Southern Levant by Dana Douglas DePietro Doctor of Philosophy in Near Eastern Studies University of California, Berkeley Professor Marian Feldman, Chair Striking changes in the archaeological record of the southern Levant during the final years of the Late Bronze Age have long fascinated scholars interested in the region and period. Attempts to explain the emergence of new forms of Canaanite material culture have typically cited external factors such as Egyptian political domination as the driving force behind culture change, relying on theoretical models of acculturation, elite-emulation and center-periphery theory. While these approaches can be useful in explaining some dimensions of culture-contact, they are limited by their assumption of a unidirectional flow of power and influence from dominant core societies to passive peripheries. -

Mephibosheth

No. 15 Mephibosheth surrounded Nathan Hiram Solomon Asaph Jeduthun Adonijah Heman Abishag “the child” Araunah Gad the Cushite Jonathan Uriah Bathsheba Nathan Ahimaaz Abiathar Chileab Zadok Ahimelech Abigail Nabal Uzzah Obed-Edom Hadadezer Samuel Benaiah Doeg Achish Goliath David Saul Merab Eliab Jonathan Michal Jesse Zeruiah Mephibosheth Ziba Rechab & Baanah Joab Abner Ishbosheth Abishiai Talmai Shimei Barzillai Absalom Tamar Asahel Sheba Amasa Amnon Hushai Ahithophel Ahinoam pe vid ople in the life of Da © 2013 Jon F. Mahar, Hakusan City, Japan, Alexander, Maine, U.S.A. about Mephibosheth 1.) Mephibosheth was introduce briefly 5.) It’s helpful to ask what connection, in 2 Sam. 4:4 as a son of Jonathan if any, there may have been between who was lame because of a childhood Mephibosheth’s godly character and accident. His age and lameness prob- his physical handicap and weak social ably disqualified him from becoming position. As the grandson of king Saul king of Israel. He was only five when it was natural for him to be afraid of his father died and probably only about David (9:6-7, 19:28). But the bigger seven or eight when his much older question is if God had used his handi- brother, King Ishbosheth, died. cap to make him a godly man. 2.) Mephibosheth was probably over- 6.) The adjective, “humble,” is derived looked and spared by those who killed from the verb “to humble” which often Ishbosheth in ch. four because of his has to do with being afflicted or op- handicap, as well as because of his pressed, like the people of Israel in young age. -

Megillat Esther

The Steinsaltz Megillot Megillot Translation and Commentary Megillat Esther Commentary by Rabbi Adin Even-Israel Steinsaltz Koren Publishers Jerusalem Editor in Chief Rabbi Jason Rappoport Copy Editors Caryn Meltz, Manager The Steinsaltz Megillot Aliza Israel, Consultant Esther Debbie Ismailoff, Senior Copy Editor Ita Olesker, Senior Copy Editor Commentary by Chava Boylan Rabbi Adin Even-Israel Steinsaltz Suri Brand Ilana Brown Koren Publishers Jerusalem Ltd. Carolyn Budow Ben-David POB 4044, Jerusalem 91040, ISRAEL Rachelle Emanuel POB 8531, New Milford, CT 06776, USA Charmaine Gruber Deborah Meghnagi Bailey www.korenpub.com Deena Nataf Dvora Rhein All rights reserved to Adin Steinsaltz © 2015, 2019 Elisheva Ruffer First edition 2019 Ilana Sobel Koren Tanakh Font © 1962, 2019 Koren Publishers Jerusalem Ltd. Maps Editors Koren Siddur Font and text design © 1981, 2019 Koren Publishers Jerusalem Ltd. Ilana Sobel, Map Curator Steinsaltz Center is the parent organization Rabbi Dr. Joshua Amaru, Senior Map Editor of institutions established by Rabbi Adin Even-Israel Steinsaltz Rabbi Alan Haber POB 45187, Jerusalem 91450 ISRAEL Rabbi Aryeh Sklar Telephone: +972 2 646 0900, Fax +972 2 624 9454 www.steinsaltz-center.org Language Experts Dr. Stéphanie E. Binder, Greek & Latin Considerable research and expense have gone into the creation of this publication. Rabbi Yaakov Hoffman, Arabic Unauthorized copying may be considered geneivat da’at and breach of copyright law. Dr. Shai Secunda, Persian No part of this publication (content or design, including use of the Koren fonts) may Shira Shmidman, Aramaic be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embedded in critical articles or reviews. -

New Early Eighth-Century B.C. Earthquake Evidence at Tel Gezer: Archaeological, Geological, and Literary Indications and Correlations

Andrews University Digital Commons @ Andrews University Master's Theses Graduate Research 1992 New Early Eighth-century B.C. Earthquake Evidence at Tel Gezer: Archaeological, Geological, and Literary Indications and Correlations Michael Gerald Hasel Andrews University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/theses Recommended Citation Hasel, Michael Gerald, "New Early Eighth-century B.C. Earthquake Evidence at Tel Gezer: Archaeological, Geological, and Literary Indications and Correlations" (1992). Master's Theses. 41. https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/theses/41 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Research at Digital Commons @ Andrews University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Andrews University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Thank you for your interest in the Andrews University Digital Library of Dissertations and Theses. Please honor the copyright of this document by not duplicating or distributing additional copies in any form without the author’s express written permission. Thanks for your cooperation. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. -

Can You Answer These Questions?

SERIES XV LECTURE IX c"qa CAN YOU ANSWER THESE QUESTIONS? 1. Describe the events that occurred immediately after the death of Joshua and the elders. 2. Describe the three ways in which the people of Israel were punished during the period of the Judges. 3. Describe five aspects which were common to both the Judges and the Kings of Israel. 4. Describe five aspects which distinguished the Judges from the Kings of Israel. 5. Who was the first of the Judges? This and much more will be addressed in the ninth lecture of this series: "The Period of the Judges: Part One". To derive maximum benefit from this lecture, keep these questions in mind as you listen to the lecture and read through the outline. Go back to these questions once again at the end of the lecture and see how well you answer them. PLEASE NOTE: This outline and source book were designed as a powerful tool to help you appreciate and understand the basis of Jewish History. Although the lectures can be listened to without the use of the outline, we advise you to read the outline to enhance your comprehension. Use it, as well, as a handy reference guide and for quick review. This lecture is dedicated to the honor and merit of Dr. and Mrs. Gabriel Sosne and their family. THE EPIC OF THE ETERNAL PEOPLE Presented by Rabbi Shmuel Irons Series XV Lecture #9 THE PERIOD OF THE JUDGES: PART ONE I. The Emergence of the Judges A. lM¨ z`¥ E`x¨ xW¤ `£ r© EWFdi§ ix¥g£`© min¦ i¨ Ekix¦`¡d¤ xW¤ `£ mip¦ w¥ G§d© in¥ i§ | loke§ r© Wª Fdi§ in¥ i§ loM 'c z`¤ mr¨ d¨ Eca§ r© I©e© FzF` ExA§ w§ I¦e© :mip¦ -

14. BIBLICAL EPIC: 2 Chronicles Notes

14. BIBLICAL EPIC: 2 Chronicles Notes rown 2 Chron 1: Solomon made offerings. God said, "What shall I give you?" Solomon said, "Wisdom to rule this people." So Solomon ruled over Israel. • 1:1-6. Solomon Worships at Gibeon. Solomon’s journey to the Mosaic tabernacle and altar at Gibeon, like David’s mission to retrieve the Ark, is presented as a public enterprise that involves all Israel. Like David, Solomon maintains continuity with the Mosaic covenant as the foundation of his own reign. Solomon begins his reign as David instructed him (1 Chron 22:19), by worshiping God and seeking guidance. “High places” were commonly associated with hills or mountains in the OT world. Prior to the construction of the temple, high places were generic worship sites that were not necessarily connected with pagan worship. The negative connotation of high places begins after the completion of the temple, after which high places were associated with idolatry and syncretism. Solomon’s extensive sacrifice at Gibeon tangibly showed his reverence for God at the outset of his reign. • 1:7-13. Solomon’s Request for Wisdom. Solomon’s faithful seeking leads to a nighttime appearance of God (in a dream, according to 1 Kings 3:5), in which God invites Solomon to ask in prayer for whatever he desires. Solomon makes two requests: (1) that God would continue to bring the fullness of the Davidic covenant (and the Abrahamic covenant) to pass (looking forward to the completion of the temple, 2 Chron 6:17) and (2) that God would grant him wisdom and knowledge. -

Buy Cheap Levitra

Excavating a Battle: The Intersection of Textual Criticism, Archaeology, and Geography The Problem of Hill City Just as similarities or variant forms of personal names can create textual problems, the same .( ֶּ֖ג ַבע) and Geba (גִּבְע ָ֔ ה) is true of geographic names. A case in point is the confusion of Gibeah Both names mean “Hill City”, an appropriate name for a city in the hill country of Benjamin, where other cities are named Lookout (Mizpeh) and Height (Ramah). Adding to the mix is the The situation is clarified (or confused further) by the modifiers that .( ִּג ְב ֥עֹון) related name Gibeon are sometimes added to the names. The difficulty of keeping these cities distinct is increased by textual problems. Sometimes “Geba” may be used for “Gibeah,” and vice versa. To complicate matters further there are other Gibeah/Geba’s in Israel (Joshua 15:57—Gibeah in Judah, Joshua 24:33 —Gibeath in Ephraim). That Gibeah and Geba in Benjamin are two different places is demonstrated by Joshua 18:24, 28, which lists ( ִּג ְב ַַ֣עת and Gibeah (here in the form ( ֶּ֖ג ַבע) both Geba among the cities of Benjamin. Isaiah 10:29 also The Gibeah we are discussing here is near .( ִּג ְב ַ֥עת ש ֶּ֖אּול) distinguishes Geba from Gibeah of Saul the central ridge, near Ramah, north of Jerusalem. Geba is further east on the edge of the wilderness, near a descent to the Jordan Valley. It is across the valley from Michmash. Gibeah Gibeah is Saul’s capital near Ramah. It is a restoration of the Gibeah destroyed in Judges. -

The Biographical Method of Bible Study (P. Rhebergen)

Method 5 - The Biographical Method of Bible Study (P. Rhebergen) 5.1 - Tools 5.1.1 - Bible 5.1.2 - Exhaustive and / or biographical concordance 5.1.3 - Topical Bible 5.1.4 - Bible dictionary or encyclopedia 5.2 - Hints 5.2.1 - Remember that the person will often be referred to by means other than his / her proper name in many passages. 5.3 - Steps Step 1 - Choose an individual from the Bible for your study. See the list below for a selection of persons from the Bible. Step 2 - List all references concerning that person. A concordance will help if the person is referred to in the Bible by their proper name, but you may also wish to look for ambiguous references to the person (ie: Pharaoh’s wife or the son of Zebedee). Step 3 - Note your first impression of the person after your first reading of the passages. Step 4 - Make a chronological outline of the person's life after your second reading. Step 5 - Obtain some insights into the person after your third reading. Step 6 - Identify some character qualities after your fourth reading. Step 7 - Show how some other Bible truths are illustrated in this person's life. Step 8 - Summarize the main lesson(s) you have learned. Step 9 - Write out a personal application. Step 10 - Make your study transferable. Step 11 - Note someone with whom you will share the results of this study and commit yourself to doing this. A Partial List of Biblical People The three following lists include some of the major men of the Bible, the minor but important men of the Bible, and the prominent women of the Bible. -

Three Conquests of Canaan

ÅA Wars in the Middle East are almost an every day part of Eero Junkkaala:of Three Canaan Conquests our lives, and undeniably the history of war in this area is very long indeed. This study examines three such wars, all of which were directed against the Land of Canaan. Two campaigns were conducted by Egyptian Pharaohs and one by the Israelites. The question considered being Eero Junkkaala whether or not these wars really took place. This study gives one methodological viewpoint to answer this ques- tion. The author studies the archaeology of all the geo- Three Conquests of Canaan graphical sites mentioned in the lists of Thutmosis III and A Comparative Study of Two Egyptian Military Campaigns and Shishak and compares them with the cities mentioned in Joshua 10-12 in the Light of Recent Archaeological Evidence the Conquest stories in the Book of Joshua. Altogether 116 sites were studied, and the com- parison between the texts and the archaeological results offered a possibility of establishing whether the cities mentioned, in the sources in question, were inhabited, and, furthermore, might have been destroyed during the time of the Pharaohs and the biblical settlement pe- riod. Despite the nature of the two written sources being so very different it was possible to make a comparative study. This study gives a fresh view on the fierce discus- sion concerning the emergence of the Israelites. It also challenges both Egyptological and biblical studies to use the written texts and the archaeological material togeth- er so that they are not so separated from each other, as is often the case. -

What Is Biblical Prophecy?

What is Biblical Prophecy? What Biblical Prophecy is NOT, and What It Really IS: Contrary to what many fundamentalist preachers or late-night radio hosts would have you believe, biblical prophecy is not primarily about “predicting the future” or finding clues in the Bible that correspond to people or events in our own day and age! The prophets of Ancient Israel did not look into some kind of crystal ball and see events happening thousands of years after their own lifetimes. The books they wrote do not contain hidden coded messages for people living in the 20th or 21st centuries! Rather, biblical prophets were mainly speaking to and writing for the people of their own time. They were challenging people of their own world, especially their political rulers, to remain faithful to God’s commandments and/or to repent and turn back to God if they had strayed. They were conveying messages from God, who had called or commissioned them, rather than speaking on their own initiative or authority. However, because the biblical prophets were transmitting messages on behalf of God (as Jews and Christians believe), much of what they wrote for their own time is clearly also relevant for people living in the modern world. The overall message of faith and repentance is timeless and applicable in all ages and cultures. To understand what biblical prophecy really is, let’s look more closely at the origins, definitions, and uses of some key biblical words. In the Hebrew Bible, the word for “prophet” is usually nabi’ (lit. “spokesperson”; used over 300 times!), while the related feminine noun nebi’ah (“prophetess”) occurs only rarely.