2020 Impact Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

28Th February 2019 - 1Pm

Minutes for Main Board meeting held at Petroc on Thursday 28th February 2019 - 1pm Attendees Mike Matthews (Chair) (MM) Janet Phillips – NDMA (JP) Bill Blythe – Vice Principal, Petroc (BB) Chris Fuller – TDC (CF) Dominie Dunbrook – NDC (DD) Trudi Spratt – Barnstaple Chamber of Commerce (TS) Nicola Williams - ESB Co-ordinator (NW) Apologies Tony George – DWP Matt Hurley – DWP 1) Matters arising from previous minutes Nordab have agreed to attend the ESB Advisory Group. Jack Jackson is now the permanent chair of Nordab. The representative is to be confirmed. ACTION: BB to discuss with Jack Jackson of who will represent Nordab at future Advisory Group meetings. 2) Matters arising from ESB co-ordinator update All agreed that the first Advisory Group meeting was a success. BB confirmed that Petroc will seek to continue to find funding for the co-ordinator post. Nicky’s current contract expires 31st August 2019. DD confirmed that there will be changes, and expecting a different administration in charge, within both local authorities, after the local elections in May. There will then be an opportunity to promote the ESB to the new full council. BB discussed about the LEP work on Skills Advisory Panels and a view that ESB’s would be an integral part of the governance for Skills Advisory Panels. ACTION: BB will pursue this with the LEP. Other ESB’s in the area TS and MM had been trying to arrange a meeting with the Plymouth ESB, who are supported by their local council. BB had met with colleagues from Mid Devon Economic Development team and they are seeking to find out how we are operating, as there are getting no value or connectivity from their ESB which is the Greater Exeter. -

Bicton College

•Department •Department for Education for Business Innovation & Skills Jeremy Yabsley Minister for Skills and Chair of Governors Equalities Bicton College 1 Victoria Street London East Budleigh SW1H OET Budleigh Salterton T +44 (0) 20 7215.5000 E [email protected] Devon www.gov.uk/bis EX97BY www.education.gov.uk 30 October 2014 A-.__ rl 1~L ~~ . I am writing to confirm the tcome of the FE Commissioner Structure and Prospect · Appraisal of your Colle , and to set out the actions we now expect the College to take to ensure the Appraisal outcomes, and the FE Commissioner's earlier assessment, are fully implemented. I am very grateful for the support that the FE Commissioner has received from yourself and the College during the Appraisal, and the steps you have taken to date to respond to the recommendations in my predecessor's letter of 22 April 2014. As you are aware, in light of the notification by the Skills Funding Agency that the College's financial health is inadequate, the FE Commissioner reviewed the position of your College between 17 and 28 March 2014. The FE Commissioner acknowledged the capacity and capability of the governance and leadership to deliver financial recovery in the short term, but concluded that the College could not continue to operate on its own. The FE Commissioner was asked to lead a Structure and Prospects Appraisal to determine the way forward for land-based provision in the area. This Appraisal was completed in September 2014. I have now received the FE Commissioner's Appraisal report - a copy of which is attached. -

Report of Surveys

North Devon and Torridge Infrastructure Planning Evidence Base Report Education, Children and Young People Waste Disposal Extra Care Housing Libraries April 2016 Devon County Council County Hall Topsham Road Exeter Devon EX2 4QD PREPARED BY Name: Christina Davey Position: Senior Planning Officer Date: April 2016 SPECIALIST INPUT FROM Children’s Services: Simon Niles (Strategic Education Manager) Libraries: Andrew Davey (Compliance and Standards Officer) Extra Care Housing: Alison Golby (Strategic Commissioning Manager-Housing) Waste: Annette Dentith (Principal Waste Management Officer - Policy) and Andy Hill (Principal Planning Officer – Minerals and Waste) AGREED BY Name: Joe Keech Position: Chief Planner Date: May 2016 Contents LIST OF TABLES ..................................................................................................... 4 1. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................ 5 1.1. Strategic planning in North Devon and Torridge ............................................. 5 1.2. Purpose of this report ..................................................................................... 5 1.3. Structure of this report .................................................................................... 5 2. THE NORTH DEVON AND TORRIDGE LOCAL PLAN 2011 - 2031 ............. 7 2.1. Distribution of development ............................................................................ 7 3. DEMOGRAPHIC OVERVIEW ....................................................................... -

Royal Holloway University of London Aspiring Schools List for 2020 Admissions Cycle

Royal Holloway University of London aspiring schools list for 2020 admissions cycle Accrington and Rossendale College Addey and Stanhope School Alde Valley School Alder Grange School Aldercar High School Alec Reed Academy All Saints Academy Dunstable All Saints' Academy, Cheltenham All Saints Church of England Academy Alsop High School Technology & Applied Learning Specialist College Altrincham College of Arts Amersham School Appleton Academy Archbishop Tenison's School Ark Evelyn Grace Academy Ark William Parker Academy Armthorpe Academy Ash Hill Academy Ashington High School Ashton Park School Askham Bryan College Aston University Engineering Academy Astor College (A Specialist College for the Arts) Attleborough Academy Norfolk Avon Valley College Avonbourne College Aylesford School - Sports College Aylward Academy Barnet and Southgate College Barr's Hill School and Community College Baxter College Beechwood School Belfairs Academy Belle Vue Girls' Academy Bellerive FCJ Catholic College Belper School and Sixth Form Centre Benfield School Berkshire College of Agriculture Birchwood Community High School Bishop Milner Catholic College Bishop Stopford's School Blatchington Mill School and Sixth Form College Blessed William Howard Catholic School Bloxwich Academy Blythe Bridge High School Bolton College Bolton St Catherine's Academy Bolton UTC Boston High School Bourne End Academy Bradford College Bridgnorth Endowed School Brighton Aldridge Community Academy Bristnall Hall Academy Brixham College Broadgreen International School, A Technology -

Masterclass Menu 2019/20

Masterclass Menu 2019/20 Immerse your students in HE learning environments, with hands-on experiences that showcase a subject-specialism at one of our partner providers. Subjects include Arts & Humanities / Science & Engineering / Business & Professional Services / Sport, Leisure & Tourism / Medicine, Health & Social Sciences /Education. To arrange a booking and discuss travel arrangements, please contact the host institution. Contact information is provided at the end of this document. *Please note all dates are subject to change, and booking requests will be allocated on a fair case-by-case basis. Arts & Humanities Masterclass Year Who? When? Description Location Vision Mix 9-13 Groups On- Using state-of-the-art broadcast vision mixing equipment and a green screen Plymouth College of of 15 request studio, your students will form a production crew to manage a live TV broadcast. Art (target They will learn how to create digital news content for production, as well as how & WP) to direct 'talent' for live broadcast events. Hot Glass 9-13 Groups of On- Working with hot glass, your students will pay homage to Jackson Pollock using Plymouth College of 10 (target request hot, liquid glass from the furnace. Exploring the properties of hot glass, each Art & WP) student will make a unique sample for their portfolios and to take home. Textiles 9-13 Groups of On- Think like a textile designer and experiment with unconventional mixed media Plymouth College of Mash-up 10 (target request samples to create a new mood. Students will combine the rough with the smooth Art (or at your school) & WP) and the grimy with the shiny, interrogating material to create a fashion or interiors vision. -

Royal Air Force Visits to Schools

Location Location Name Description Date Location Address/Venue Town/City Postcode NE1 - AFCO Newcas Ferryhill Business and tle Ferryhill Business and Enterprise College Science of our lives. Organised by DEBP 14/07/2016 (RAF) Enterprise College Durham NE1 - AFCO Newcas Dene Community tle School Presentations to Year 10 26/04/2016 (RAF) Dene Community School Peterlee NE1 - AFCO Newcas tle St Benet Biscop School ‘Futures Evening’ aimed at Year 11 and Sixth Form 04/07/2016 (RAF) St Benet Biscop School Bedlington LS1 - Area Hemsworth Arts and Office Community Academy Careers Fair 30/06/2016 Leeds Hemsworth Academy Pontefract LS1 - Area Office Gateways School Activity Day - PDT 17/06/2016 Leeds Gateways School Leeds LS1 - Area Grammar School at Office The Grammar School at Leeds PDT with CCF 09/05/2016 Leeds Leeds Leeds LS1 - Area Queen Ethelburgas Office College Careers Fair 18/04/2016 Leeds Queen Ethelburgas College York NE1 - AFCO Newcas City of Sunderland tle Sunderland College Bede College Careers Fair 20/04/2016 (RAF) Campus Sunderland LS1 - Area Office King James's School PDT 17/06/2016 Leeds King James's School Knareborough LS1 - Area Wickersley School And Office Sports College Careers Fair 27/04/2016 Leeds Wickersley School Rotherham LS1 - Area Office York High School Speed dating events for Year 10 organised by NYBEP 21/07/2016 Leeds York High School York LS1 - Area Caedmon College Office Whitby 4 x Presentation and possible PDT 22/04/2016 Leeds Caedmon College Whitby Whitby LS1 - Area Ermysted's Grammar Office School 2 x Operation -

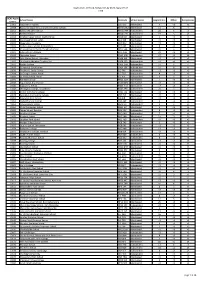

6.1 Import-Export-Plymouth

6.1 Total Imports 1,467 Total Exports 1,409 Import / Export Adjustment 58.0 Provider LA name Plymouth (879) Import/Export Type (All) Sum of Pupils/Students Resident LA name Institution type LAESTAB URN UKPRN Establishment name Devon (878) Plymouth (879) Torbay (880) Cornwall (908) Total Grand Maintained special schools and special academies 8797062 113644 10015104 Woodlands School 9 63 9 81 Maintained special schools and special academies 8797063 113645 10017862 Cann Bridge School 5 78 1 84 Maintained special schools and special academies 8797065 144009 10062557 Courtlands School 1 72 1 74 Maintained special schools and special academies 8797066 113648 10015768 Brook Green Centre for Learning 8 86 94 Maintained special schools and special academies 8797067 113649 10018147 Mount Tamar School 6 95 1 3 105 Maintained special schools and special academies 8797068 113650 10016325 Longcause Community Special School 5 96 1 102 Maintained special schools and special academies 8797069 113651 10016486 Mill Ford School 4 85.5 7 96.5 Maintained special schools and special academies Total 38 575.5 1 22 636.5 Mainstream maintained schools and academies 8792681 143309 10057750 Widey Court Primary School 2 4 6 Mainstream maintained schools and academies 8792694 142688 10056162 Boringdon Primary School 1 2 3 Mainstream maintained schools and academies 8792703 143312 10057748 Eggbuckland Vale Primary School 1 18 19 Mainstream maintained schools and academies 8794001 139923 10042730 Plymouth School of Creative Arts 4 24 1 29 Mainstream maintained schools -

SWIOT Brochure

1 OUR MISSION THE VISION Working in partnership to drive We will help What we will achieve: world-class technical education. deliver FOR EMPLOYERS - SWIOT WILL: FOR LEARNERS - SWIOT WILL: The mission of the South West Institute of Technology is to: > tackle employers’ current skills > offer industry standard teaching skilled gaps and anticipate their future and facilities and new curriculum > provide employers with the skills that they need to succeed, now and in skills needs, drawing on applied in the digital, engineering and the future local people, research manufacturing sectors > provide learners with excellent technical education economic > enable employers to develop and > inspire and raise the aspirations > enable the South West to become one of the world’s leading regions for retain local talent, reducing the of learners, from school students digital, engineering and manufacturing technologies. growth and need to recruit from outside of to lifelong learners the region prosperity > provide learners with the non- Anchor HE Partners in the > provide industry standard, academic skills required in the specialist training facilities modern workplace, as well as South West. locally, reducing the need to technical skills train outside of the region > increase social mobility, reach > put in place learning provision under-represented groups, develop that is tailored to the needs of unidentified talent and improve employers, more quickly gender balance > enable the existing workforce > break down geographical barriers, to retrain and upskill, -

University Technology College for Plymouth Committee: Cabinet Date

PLYMOUTH CITY COUNCIL Subject: University Technology College for Plymouth Committee: Cabinet Date: 21 February 2012 Cabinet Member: Councillor Samantha Leaves CMT Member: Director for People and the Director for Place Author: Gareth Simmons, Programme Director for Learning Environments Contact: Tel: 01752 307161, [email protected] Ref: Key Decision: Yes Part: I Executive Summary: In the Spring of 2011 the Secretary of State for Education announced that a number of University Technical Colleges (UTCs) would be developed across the country. Following this announcement an application process was developed for universities and colleges to submit bids for UTC funding. The closing date was mid June 2011. A consortium of Plymouth University, City College Plymouth - the College of Further Education and Plymouth City Council, developed a vision to promote employer led learning in Plymouth that would be delivered through a UTC. The University, who acted as lead sponsors, City College and leading employers formed a limited company in order to make a bid for a UTC based at a Devonport location. They were supported in this by, amongst others, Babcock Marine, Princess Yachts International, Plymouth Manufacturers Group, Plymouth Chamber of Commerce and Industry and Plymouth Federation of Small Businesses. On 10 October 2011 the Government announced that a number of UTCs would be taken forward including one in Plymouth. The announcement made clear that the Secretary of State hoped that Plymouth UTC would be opened in 2014, but there were possibilities of an earlier start in 2013. Plymouth University, Plymouth City College and Babcock Marine are developing the governance arrangements of what will become a UTC Academy Trust. -

Your Excellent Improvement in GCSE Results

Park News Summer 2014 web: parkcommunity.devon.sch.uk “An exciting world of challenge and opportunity” School is all about achieving your very best whilst enjoying life, having some fun and being happy with friends, helping others and playing your part. Our approach is to encourage, motivate, inspire and support each student to achieve his or her very best in all aspects of life. We do this via a very broad range of challenge and opportunity, opening eyes to new ideas, new interests and the high expectations of all that can be possible, with imagination and creativity combined with a secure understanding of just how the modern world is moving forward so rapidly. In every edition of Park News you will read of our students and their lives – all that they achieve, their successes, adventures and how they help others. Our Ofsted Inspection and the congratulations of David Laws, the Minister of State for Schools, for being in the Top 100 Schools Nationally for GCSE Improvement, confirms our quality and this magazine shows how this impacts upon the rounded development and future life opportunities of each boy and girl in the school. David Atton - Headteacher 1. “Your Excellent Improvement in GCSE Results” One of the Top 100 Schools in England This proved a very enjoyable evening for all present as A World of Academic each received deserved recognition for their outstanding achievement. Their citations described the highest Success standards secured and both the depth and breadth of talent and scholarship demonstrated by each. We look Our students’ success at GCSE builds in a determined and forward to their excellent GCSE results in the years ahead. -

Devon Schools Cross Country Team South West Schools Cross Country Championships Saturday 3Rd February Stover School

Devon Schools Cross Country Team South West Schools Cross Country Championships Saturday 3rd February Stover School Minor Boys (YR7) Pen Order Name School 1 Will Pengelly Park 2 Kyle Pearson Park 3 Thomas Jones Ivybridge 4 Henry Richards Shebbear 5 Sam Gammon King’s 6 Xavier Bly Kingsbridge 7 Jack Emmett Uffculme 8 William White Tavistock 9 Ben Crook Colyton 10 Isaac Astbury Torquay Academy Reserves Non- Travelling 1 Luke Pascoe Teign 2 Seb Marshall Brixham 3 Giles Brock South Molton 4 Jaspar Kolowska Blundells Junior Boys (YRS 8 & 9) Pen Order Name School 1 Olly Capps Exeter School 2 Sam Mills Clyst Vale 3 Adam Leworthy Bideford 4 Ethan Philipson Hele’s 5 Dylan Dayman Park 6 Euan Botham Mount Kelly 7 William Russell Tavistock 8 Joe Dix Tavistock 9 Sam Priday Okehampton 10 Tor Swann South Dartmoor Reserves Non- Travelling 1 Louis Chamberlain St James 2 Kieran Williams Blundells 3 Dom Sloper Churston 4 Ben Sheridan Kings Inter Boys (YRS 10 & 11) Pen Order Name School 1 Oliver Smart Mount Kelly 2 Flynn Jennings Bideford 3 Johnny Livingstone Colyton 4 James Alcock St Cuthbert Mayne 5 Simon Davis Colyton 6 Rio Turl Isca 7 Ben Woodland Braunton 8 Josh Miller Sidmouth 9 Charlie Tapp St Peter’s 10 Hamish James Park Reserves Non- Travelling 1 Charlie Arnold King’s 2 Sid Baldaro Pilton 3 George Greensmith West Buckland 4 Luca Taylor-Hayden QECC Senior Boys (YRS 12 & 13 ) Pen Order Name School 1 Callum Choules Petroc 2 Joseph Battershill Ivybridge 3 Toby Garrick Sidmouth 4 Jamie Williams DHSB 5 Oliver Caute Exeter College 6 Tom Brew Mount Kelly -

2014 Admissions Cycle

Applications, Offers & Acceptances by UCAS Apply Centre 2014 UCAS Apply School Name Postcode School Sector Applications Offers Acceptances Centre 10002 Ysgol David Hughes LL59 5SS Maintained 4 <3 <3 10008 Redborne Upper School and Community College MK45 2NU Maintained 11 5 4 10011 Bedford Modern School MK41 7NT Independent 20 5 3 10012 Bedford School MK40 2TU Independent 19 3 <3 10018 Stratton Upper School, Bedfordshire SG18 8JB Maintained 3 <3 <3 10020 Manshead School, Luton LU1 4BB Maintained <3 <3 <3 10022 Queensbury Academy LU6 3BU Maintained <3 <3 <3 10024 Cedars Upper School, Bedfordshire LU7 2AE Maintained 4 <3 <3 10026 St Marylebone Church of England School W1U 5BA Maintained 20 6 5 10027 Luton VI Form College LU2 7EW Maintained 21 <3 <3 10029 Abingdon School OX14 1DE Independent 27 13 13 10030 John Mason School, Abingdon OX14 1JB Maintained <3 <3 <3 10031 Our Lady's Abingdon Trustees Ltd OX14 3PS Independent <3 <3 <3 10032 Radley College OX14 2HR Independent 10 4 4 10033 St Helen & St Katharine OX14 1BE Independent 14 8 8 10036 The Marist Senior School SL5 7PS Independent <3 <3 <3 10038 St Georges School, Ascot SL5 7DZ Independent 4 <3 <3 10039 St Marys School, Ascot SL5 9JF Independent 6 3 3 10041 Ranelagh School RG12 9DA Maintained 7 <3 <3 10043 Ysgol Gyfun Bro Myrddin SA32 8DN Maintained <3 <3 <3 10044 Edgbarrow School RG45 7HZ Maintained <3 <3 <3 10045 Wellington College, Crowthorne RG45 7PU Independent 20 6 6 10046 Didcot Sixth Form College OX11 7AJ Maintained <3 <3 <3 10048 Faringdon Community College SN7 7LB Maintained