Vaccine Beliefs of Complementary and Alternative Medical (CAM) Providers in Oregon

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

0 January to July 2021

0 www.journalsofindia.com January to July 2021 SCIENCE & TECH ............................................................................................................................................................... 6 1. REUSABLE LAUNCH VEHICLE TECHNOLOGY DEMONSTRATION PROGRAMME(RLV-TD) ................................................. 6 2. GAGANYAAN MISSION ..................................................................................................................................................... 6 3. MARS ORBITER MISSION (MOM) ..................................................................................................................................... 6 4. CHANDRAYAAN MISSION................................................................................................................................................. 7 5. SOLAR MISSION ............................................................................................................................................................... 8 6. ARTEMIS ACCORD ............................................................................................................................................................ 9 7. NATIONAL MISSION ON INTERDISCIPLINARY CYBER-PHYSICAL SYSTEM (NMICPS) ....................................................... 10 8. SMART ANTI-AIRFIELD WEAPON (SAAW) ...................................................................................................................... 10 9. AQUAPONICS ................................................................................................................................................................ -

White Paper on Studying the Safety of the Childhood Immunization Schedule for the Vaccine Safety Datalink

White Paper on Studying the Safety of the Childhood Immunization Schedule For the Vaccine Safety Datalink National Center for Emerging and Zoonotic Infectious Diseases Immunization Safety Office CS258953 White Paper on the Safety of the Childhood Immunization Schedule Vaccine Safety Datalink Centers for Disease Control and Prevention | 1600 Clifton Road | Atlanta GA 30329 Notice: The project that is the subject of this report was approved and funded by the Immunization Safety Office, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The contributors responsible for the content of the White Paper were funded by Task Order contract 200-2012-53582/0004 awarded as a prime contract to Kaiser Foundation Hospitals. The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Additional copies of this report are available from Jason Glanz, PhD, [email protected] Contributors to the White Paper on the Study of the Safety of the Childhood Immunization Schedule Study Team Authors Jason M. Glanz, PhD Lead Investigator, Kaiser Permanente Colorado, Denver, CO; Assistant Professor of Epidemiology, University of Colorado School of Public Health, Aurora, CO. Sophia R. Newcomer, MPH Co-Investigator, Kaiser Permanente Colorado, Denver, CO. Mike L. Jackson, PhD, MPH Co-Investigator, Group Health Cooperative, Seattle, WA. Saad B. Omer, MBBS, MPH, PhD Co-Investigator and Associate Professor of Global Health, Epidemiology, and Pediatrics at Emory University, Schools of Public Health and Medicine, Atlanta, GA. Robert A. Bednarczyk, PhD Co-Investigator and Assistant Professor of Global Health, Emory University School of Public Health, Atlanta, GA. -

The Problem with Dr Bob's Alternative Vaccine Schedule Paul A

SPECIAL ARTICLE The Problem With Dr Bob’s Alternative Vaccine Schedule Paul A. Offit, MDa,b, Charlotte A. Moser, BSa aVaccine Education Center, Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; bDepartment of Pediatrics, School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania Financial Disclosure: Dr Offit is the coinventor of and co-patent holder for RotaTeq. What’s Known on this Subject What This Study Adds Many books misrepresenting the science of vaccines or vaccine safety have been pub- This article reviews the flaws in Dr Sears’ logic, as well as misinformation contained in his lished. None has been as influential as that published by Dr Robert Sears, The Vaccine book that likely will lead parents to make the wrong decisions for their children. Book: Making the Right Decision for Your Child. ABSTRACT In October 2007, Dr Robert Sears, in response to growing parental concerns about the safety of vaccines, published The Vaccine Book: Making the Right Decision for Your Child. Sears’ book is enormously popular, having sold Ͼ40 000 copies. At the back www.pediatrics.org/cgi/doi/10.1542/ of the book, Sears includes “Dr Bob’s Alternative Vaccine Schedule,” a formula by peds.2008-2189 which parents can delay, withhold, separate, or space out vaccines. Pediatricians doi:10.1542/peds.2008-2189 now confront many parents who insist that their children receive vaccines Key Words according to Sears’ schedule, rather than that recommended by the American vaccines, schedule, adverse reactions Academy of Pediatrics, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and the Abbreviations CDC—Centers for Disease Control and American Academy of Family Physicians. -

Journal of Vaccines & Vaccination

ccines & a V f V a o c l c i a n n a r t u i o o n J Ching, et al., J Vaccines Vaccin 2014, 5:6 Journal of Vaccines & Vaccination DOI: 10.4172/2157-7560.1000257 ISSN: 2157-7560 Research Article Open Access Evaluation of a Recombinant Vaccine Candidate r56Lc-1 in a Chigger Challenge Mouse Model Wei-Mei Ching1,3*, Woradee Lurchachaiwong2, Zhiwen Zhang1,3 Temitayo Awoyomi1,3, Chien-Chung Chao1,3 and Anthony Schuster2 1Viral and Rickettsial Diseases Department, Infectious Diseases Directorate, Naval Medical Research Center, Silver Spring, USA 2Entomology Department, Armed Forces Research Institute of Medical Sciences, Bangkok, Thailand 3Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, Bethesda, USA *Corresponding author: Wei-Mei Ching, PhD, Viral and Rickettsial Diseases Department, Infectious Diseases Directorate, Naval Medical Research Center, 503 Robert Grant Ave, RM3N71, Silver Spring, MD 20910, USA, Tel: 301 319 7438; Fax: 301 319 7451; E-mail: [email protected] Received date: 15 Sep 2014; Accepted date: 24 Oct 2014; Published date: 27 Oct 2014 Copyright: © 2014 Ching WM, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. Abstract Scrub typhus, an acute, febrile disease is transmitted by the bite of an Orientia infected chigger. We evaluated the protective potential of a recombinant 56 kDa antigen in a chigger challenge mouse model which mimics the natural transmission of Orientia. Chiggers from an L. -

Vaccination and Anaphylaxis

14 FORENSIC SCIENCE Croat Med J. 2017;58:14-25 https://doi.org/10.3325/cmj.2017.58.14 Vaccination and anaphylaxis: a Cristian Palmiere1, Camilla Tettamanti2, Maria Pia forensic perspective Scarpelli1 1CURML, University Center of Legal Medicine, Lausanne 25, Switzerland 2Department of Legal Medicine, Aim To review the available literature pertaining to fatali- University of Genova, Genova, Italy ties following vaccine administration and, in particular, cas- es of vaccine-related fatal anaphylaxis. Method The MEDLINE database was systematically searched up to March 2016 to identify all relevant articles pertaining to fatal cases of anaphylaxis following vaccine administration. Results Six papers pertaining to fatal anaphylaxis following vaccination were found relevant. Mast cell tryptase and to- tal IgE concentration was assessed exclusively in one case. Laryngeal edema was not detected in any of these cases, whereas eosinophil or mast cell infiltration was observed in lymphoid organs. In one case, immunohistochemical in- vestigations using anti-tryptase antibodies allowed pulmo- nary mast cells and degranulating mast cells with tryptase- positive material outside to be identified. Conclusion In any suspected IgE-mediated fatal anaphy- lactic cases, biochemical investigations should be system- atically performed for forensic purposes. Splenic tissue should be routinely sampled for immunohistochemical investigations in all suspected anaphylaxis-related deaths and mast cell/eosinophil infiltrations should be systemati- cally sought out in -

Public Trust in Vaccines: Defining a Research Agenda

Public Trust in Vaccines: Defining a Research Agenda A Report of the American Academy of Arts & Sciences American Academy of Arts & Sciences Cherishing Knowledge, Shaping the Future Since its founding in 1780, the American Academy has served the nation as a champion of scholarship, civil dialogue, and useful knowledge. As one of the nation’s oldest learned societies and independent policy research centers, the Academy convenes leaders from the academic, business, and government sectors to address critical challenges facing our global society. Through studies, publications, and programs on Science, Engineering, and Technology; Global Security and Energy; the Humanities, Arts, and Educa- tion; and American Institutions and the Public Good, the Academy provides authoritative and nonpartisan policy advice to decision-makers in government, academia, and the private sector. Public Trust in Vaccines: Defining a Research Agenda A Report of the American Academy of Arts & Sciences © 2014 by the American Academy of Arts and Sciences All rights reserved. This publication is available online at http://www.amacad.org/vaccines. Suggested citation: American Academy of Arts and Sciences, Public Trust in Vaccines: Defining a Research Agenda (Cambridge, Mass.: American Academy of Arts and Sciences, 2014). Cover image: © LWA/Dann Tardif/Getty Images. ISBN: 0-87724-098-1 The views expressed in this volume are those held by the contributors and are not necessarily those of the Officers and Fellows of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. Please direct inquiries to: American Academy of Arts and Sciences 136 Irving Street Cambridge, MA 02138-1996 Telephone: 617-576-5000 Fax: 617-576-5050 Email: [email protected] Web: www.amacad.org Contents 1 Preface 3 Introduction 5 Key Issues 9 A Proposed Research Agenda 13 Workshop Participants Preface Recent headlines tell the story. -

India: the World's Pharmacy Expands Its Reach in Global Health

New York | New Delhi | Rio de Janeiro Nairobi | Johannesburg | London India: The World’s Pharmacy Expands Its Reach in Global Health March 2021 This white paper was last updated on 1 March 2021 Global Health Strategies 18/1, 2nd Floor Shaheed Bhawan, Aruna Asaf Ali Marg, New Delhi, 110 067 www.globalhealthstrategies.com Twitter: @GHS Contents Executive Summary 02 India’s response to COVID-19 03 ∙ Pharmaceuticals and Biosimilars 04 ∙ Vaccines 05 ∙ Diagnostics 06 Evolution of India’s pharmaceutical industry 07 ∙ Milestones 08 Case Studies ∙ Hepatitis B Vaccine 10 ∙ Anti-retroviral Drugs 11 ∙ MenAfriVac 12 ∙ Complex Generics 13 ∙ Insulin 14 ∙ Monoclonal Antibodies 15 ∙ Vaccine for Rotavirus 16 ∙ Typhoid Conjugate Vaccine 17 Conclusion: Looking Forward 18 Executive Summary India’s pharmaceutical industry is already playing a pivotal role in the scale-up of pharmaceuticals and diagnostics to combat the global COVID-19 pandemic. It is poised to play an even more dominant role as biological products – preventive vaccines and cutting-edge biotechnology such as monoclonal antibodies– come to the fore. Even before the pandemic, Indian manufacturers produced vast quantities of generic antiviral drugs that turned HIV from a death sentence to a chronic manageable condition in developing countries. India’s global dominance in generic drugs and vaccine manufacturing has earned it the label “Pharmacy of the World”. COVID-19 only strengthens the case for this moniker. So far, India has supplied medicines to 133 countries to fight the pandemic. Six Indian manufacturers have been granted royalty-free licenses by Gilead to manufacture the first antiviral drug approved by the U.S. -

Vaccine Myths: Setting the Record Straight

Journal of Family Strengths Volume 18 Issue 1 Critical Issues: Defining and Debunking Misconceptions in Health, Education, Criminal Article 13 Justice, and Social Work/Social Services October 2018 Vaccine Myths: Setting the Record Straight Julie A. Boom Baylor College of Medicine, [email protected] Rachel M. Cunningham Texas Childrens Hospital, [email protected] Lindy U. McGee Baylor College of Medicine, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.library.tmc.edu/jfs Recommended Citation Boom, Julie A.; Cunningham, Rachel M.; and McGee, Lindy U. (2018) "Vaccine Myths: Setting the Record Straight," Journal of Family Strengths: Vol. 18 : Iss. 1 , Article 13. Available at: https://digitalcommons.library.tmc.edu/jfs/vol18/iss1/13 The Journal of Family Strengths is brought to you for free and open access by CHILDREN AT RISK at DigitalCommons@The Texas Medical Center. It has a "cc by-nc-nd" Creative Commons license" (Attribution Non- Commercial No Derivatives) For more information, please contact [email protected] Boom et al.: Vaccine Myths Introduction Vaccines are one of the most important public health achievements of the 20th century and are responsible for the steep decline in vaccine- preventable diseases (VPDs) in the U.S. The incidence of most VPDs in the U.S. has declined by 90 to 100% (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 1999) (see Table 1). Table 1. Vaccine-preventable diseases: post-vaccine percent decrease in morbidity. Pre-Vaccine Estimated 2016 Reported Percentage Disease Annual Cases* Decrease Morbidity† Smallpox 29,005 0 100% Diphtheria 21,053 0 100% Measles 530,162 85 99.98% Mumps 155,760 6,369 95.91% Pertussis 185,120 17,972 90.29% Polio (paralytic) 16,316 0 100% Rubella 47,734 1 100% Congenital Rubella 151 2 98.68% Syndrome Tetanus 539 34 93.69% †Source: Roush, Murphy, and the Vaccine-Preventable Disease Table Working Group (2007). -

Medical Advice and Vaccinating: What Liability?

Medical Advice and Vaccinating: What Liability? Amanda Naprawa1 and Dorit Reiss2 Abstract: Outbreaks of vaccine preventable diseases have increased over the last years. This is due in large part to the growth of the number of people who choose not to vaccinate their children. This article focuses on the role of the doctor and the doctor's advice in making the decision to vaccinate or not. In some circumstances, a doctor should be liable if an unvaccinated patient contracts a disease and is harmed herself or infects others. The starting point of the article is that vaccination is recommended by professional organizations, supported by a majority of physicians, is the safer course, and hence advising to vaccinate on schedule is the standard of care. Given that, the article argues that doctors advising vaccination should not be liable if parents reject that advice. In contrast, doctors who do not recommend vaccination should be liable. This includes both doctors that passively accept a decision not to vaccinate and doctors who advise against regulation, though the latter are more culpable and may be subject to higher liability. 1 Amanda Zibners Naprawa is a graduate of The Ohio State University Moritz College of Law where she has taught as an Adjunct Instructor of Appellate Advocacy. She is currently pursuing a Masters of Public Health (MPH) from the University of California, Berkeley. 2 Dorit Reiss, Professor of Law, UC Hastings College of the Law. !1 Introduction:3 In response to a measles outbreak in Disneyland and criticism directed at him for his role in it, Dr. -

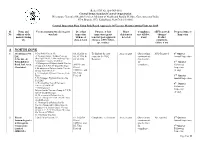

Production Flow Sheet

(Refer SOP No. QA-INS-010) Central Drugs Standard Control Organization Directorate General of Health Services, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India FDA Bhavan, ITO, Kotla Road, New Delhi -110002 Central Inspection Plan Using Risk Based Approach Of Vaccine Manufacturing Units for 2019 Sl. Name and Vaccines manufactured (category Dt. of last Purpose of last Major Compliance AEFI reported/ Proposed time of No. address of the wise list) inspection inspection (grant deficiencies met till date, changes/ Inspection manufacturing with no of /renewal /post-approval detected if any Product site days & team changes, AEFI, follow- complaints, up, routine) failure if any A NORTH ZONE 1 M/s Biomed Pvt. 1.Oral Polio Vaccine IP, 03.10.2018 to To find out the root As per report Observations NSQ Reported 1st Quarter Ltd, 2. Vi olysaccharide Typhoid Vaccine 06.10.2018 & cause for the NSQ communicate Annual Inspection C-96, Site –I, (Bio TyphTM) IP, 3. Haemophilus Type- 08.10.2018 Reported d to the firm Bulandshahar B Conjugate Vaccine (PedaHib) for 2nd Quarter 4. Meningococal Polysaccharide Vaccine ADC(I) and compliance. Follow-up Road, Ind. Area, (Group A,C,Y,W 135) QuadriMeningo Ghaziabad. 5. Meningococal Polysaccharide Vaccine DIs of Inspection (Group A&C) Bivalent CDSCO, , and (if any) 6. Vi Conjugate Typhoid Vaccine (Peda DI, Uttar Typh), Pradesh 3rd Quarter 7. Vi Conjugate Typhoid Vaccine (Bio Annual Inspection TyphTM), 8. Haemophilus Type-B Conjugate 4th Quarter Vaccine (PedaHib) IP Follow-up 9. Meningococal Inspection Polysaccharide Vaccine (Group A,C,Y,W 135) IP QuadriMeningo (if any) 10. -

Requirements for Diphtheria. Tetanus. Pertussis and Combined Vaccines

0World Health Organization World Health Or_panizatior?. Technics; Rsporr Series. Xo . S0.l . 1990 Annex 2 REQUIREMENTS FOR DIPHTHERIA. TETANUS. PERTUSSIS AND COMBINED VACCINES (Requirements for Biological Substances Nos. 8 and 10) (Revised 1989) Page Introduction ....................................................................................................... 88 Requirements for diphtheria vaccine (adsorbed) ............................................ 91 General considerations ........................................................................... 91 Part A . Manufacturing requirements .......................................................... A .1 Definit~ons............................................................................. A.2 General manufacturing requirements .................................... A.3 Production control ................................................................ A.4 Filling and containers ........................................................... A.5 Control of final product ........................................................ A.6 Records ................................................................................. A.7 Samples ................................................................................. A.8 Labelling ................................................................................ A.9 Distribution and transport .................................................... A.10 Stability . storage and expir>-date ..................................... Part B . Kational control -

WHO Expert Committee on Biological Standardization of Publications

WHOWHOWHO Technical Technical Technical Report Report Report Series Series Series 941941941 BIOLOGICAL BIOLOGICAL BIOLOGICAL ThisThisThis report report report presents presents presents the the recommendationsthe recommendations recommendations of ofa ofWHOa WHOa WHO Expert Expert Expert WHOWHOWHO EXPERT EXPERT EXPERT COMMITTEE COMMITTEE COMMITTEE CommitteeCommitteeCommittee commissioned commissioned commissioned to tocoordinate tocoordinate coordinate activities activities activities leading leading leading to tothe tothe adoptionthe adoption adoption of ofinternational ofinternational international recommendations recommendations recommendations for for the for the the ONONON BIOLOGICAL BIOLOGICAL BIOLOGICAL productionproductionproduction and and andcontrol control control of ofvaccines ofvaccines vaccines and and andother other other biologicals biologicals biologicals STANDARDIZATION STANDARDIZATION STANDARDIZATION andand andthe the establishmentthe establishment establishment of ofinternational ofinternational international biological biological biological reference reference reference STANDARDIZATIONSTANDARDIZATIONSTANDARDIZATION materials.materials.materials. TheThe Thereport report report starts starts starts with with with a discussiona discussiona discussion of ofgeneral ofgeneral general issues issues issues brought brought brought to tothe tothe attentionthe attention attention of ofthe ofthe Committeethe Committee Committee and and andprovides provides provides information information information onon theon the statusthe