Vegetative Propagation in Relation to Japanese Forest Tree Improvement

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Thuja Plicata Has Many Traditional Uses, from the Manufacture of Rope to Waterproof Hats, Nappies and Other Kinds of Clothing

photograph © Daniel Mosquin Culturally modified tree. The bark of Thuja plicata has many traditional uses, from the manufacture of rope to waterproof hats, nappies and other kinds of clothing. Careful, modest, bark stripping has little effect on the health or longevity of trees. (see pages 24 to 35) photograph © Douglas Justice 24 Tree of the Year : Thuja plicata Donn ex D. Don In this year’s Tree of the Year article DOUGLAS JUSTICE writes an account of the western red-cedar or giant arborvitae (tree of life), a species of conifers that, for centuries has been central to the lives of people of the Northwest Coast of America. “In a small clearing in the forest, a young woman is in labour. Two women companions urge her to pull hard on the cedar bark rope tied to a nearby tree. The baby, born onto a newly made cedar bark mat, cries its arrival into the Northwest Coast world. Its cradle of firmly woven cedar root, with a mattress and covering of soft-shredded cedar bark, is ready. The young woman’s husband and his uncle are on the sea in a canoe carved from a single red-cedar log and are using paddles made from knot-free yellow cedar. When they reach the fishing ground that belongs to their family, the men set out a net of cedar bark twine weighted along one edge by stones lashed to it with strong, flexible cedar withes. Cedar wood floats support the net’s upper edge. Wearing a cedar bark hat, cape and skirt to protect her from the rain and INTERNATIONAL DENDROLOGY SOCIETY TREES Opposite, A grove of 80- to 100-year-old Thuja plicata in Queen Elizabeth Park, Vancouver. -

Contributions to the Life-History of Tetraclinis Articu- Lata, Masters, with Some Notes on the Phylogeny of the Cupressoideae and Callitroideae

Contributions to the Life-history of Tetraclinis articu- lata, Masters, with some Notes on the Phylogeny of the Cupressoideae and Callitroideae. BY W. T. SAXTON, M.A., F.L.S., Professor of Botany at the Ahmedabad Institute of Science, India. With Plates XLIV-XLVI and nine Figures in the Text. INTRODUCTION. HE Gum Sandarach tree of Morocco and Algeria has been well known T to botanists from very early times. Some account of it is given by Hooker and Ball (20), who speak of the beauty and durability of the wood, and state that they consider the tree to be probably correctly identified with the Bvlov of the Odyssey (v. 60),1 and with the Ovlov and Ovia of Theo- phrastus (' Hist. PI.' v. 3, 7)/ as well as, undoubtedly, with the Citrus wood of the Romans. The largest trees met with by them, growing in an un- cultivated state, were about 30 feet high. The resin, known as sandarach, is stated to be collected by the Moors and exported to Europe, where it is used as a varnish. They quote Shaw (49 a and b) as having described and figured the tree under the name of Thuja articulata, in his ' Travels in Barbary'; this statement, however, is not accurate. In both editions of the work cited the plant is figured and described as ' Cupressus fructu quadri- valvi, foliis Equiseti instar articulatis '. Some interesting particulars of the use of the timber are given by Hansen (19), who also implies that the embryo has from three to six cotyledons. Both Hooker and Ball, and Hansen, followed by almost all others who have studied the plant, speak of it as Callitris qtiadrivalvis. -

Seiridium Canker of Cypress Trees in Arizona Jeff Schalau

ARIZONA COOPERATIVE E TENSION AZ1557 January 2012 Seiridium Canker of Cypress Trees in Arizona Jeff Schalau Introduction Leyland cypress (x Cupressocyparis leylandii) is a fast- growing evergreen that has been widely planted as a landscape specimen and along boundaries to create windbreaks or privacy screening in Arizona. The presence of Seiridium canker was confirmed in Prescott, Arizona in July 2011 and it is suspected that the disease occurs in other areas of the state. Seiridium canker was first identified in California’s San Joaquin Valley in 1928. Today, it can be found in Europe, Asia, New Zealand, Australia, South America and Africa on plants in the cypress family (Cupressaceae). Leyland cypress, Monterey cypress, (Cupressus macrocarpa) and Italian cypress (C. sempervirens) are highly susceptible and can be severely impacted by this disease. Since Leyland and Italian cypress have been widely planted in Arizona, it is imperative that Seiridium canker management strategies be applied and suitable resistant tree species be recommended for planting in the future. The Pathogen Seiridium canker is known to be caused by three different fungal species: Seiridium cardinale, S. cupressi and S. unicorne. S. cardinale is the most damaging of the three species and is SCHALAU found in California. S. unicorne and S. cupressi are found in the southeastern United States where the primary host is JEFF Leyland cypress. All three species produce asexual fruiting Figure 1. Leyland cypress tree with dead branch (upper left) and main leader bodies (acervuli) in cankers. The acervuli produce spores caused by Seiridium canker. (conidia) which spread by water, human activity (pruning and transport of infected plant material), and potentially insects, birds and animals to neighboring trees where new Symptoms and Signs infections can occur. -

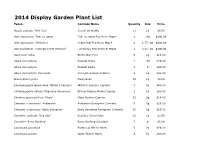

2014 Display Garden Plant List

2014 Display Garden Plant List Taxon Common Name Quantity Size Price Acacia cognata 'Mini Cog' Cousin Itt Wattle 11 1g $8.00 Acer japonicum 'Taki-no-gawa' Taki-no-gawa Full Moon Maple 1 15g $200.00 Acer japonicum 'Vitifolium' Grape-leaf Full Moon Maple 2 1.75" cal $200.00 Acer palmatum 'Twombly's Red Sentinel' Twombly’s Red Sentinel Maple 1 2.25" cal $300.00 Asplenium nidus Bird's Nest Fern 5 1g $10.00 Azara microphylla Boxleaf Azara 1 15g $75.00 Azara microphylla Boxleaf Azara 3 5 $40.00 Azara microphylla 'Variegata' Variegated Boxleaf Azara 6 5g $45.00 Brachyglottis greyi Daisy Bush 15 1g $5.00 Chamaecyparis lawsoniana 'Wissel’s Saguaro' Wissel’s Saguaro Cypress 3 5g $60.00 Chamaecyparis obtusa 'Pygmaea Aurescens' Bronze Pygmy Hinoki Cypress 1 15 $60.00 Chamaecyparis pisifera 'Mops' Mops Sawara Cypress 20 2g $14.00 Clematis x cartmanii 'Avalanche' Avalanche Evergreen Clematis 5 5g $25.00 Clematis x cartmanii 'Early Sensation' Early Sensation Evergreen Clematis 10 5g $25.00 Cordyline australis 'Red Star' Red Star Grass Palm 12 1g $7.00 Corydalis 'Berry Exciting' Berry Exciting Corydalis 7 q $5.00 Corylopsis pauciflora Buttercup Winter Hazel 5 2g $26.00 Corylopsis spicata Spike Winter Hazel 4 5g $40.00 Crinodendron hookerianum Chilean Lantern Tree 2 10g $50.00 Cryptomeria japonica 'Black Dragon' Black Dragon Japanese Cedar 1 2g $20.00 Cryptomeria japonica 'Cristata' Cockscomb Japanese Cedar 1 15 $200.00 Daphne odora 'Zuiko Nishiki' Zuiko Nishiki Winter Daphne 7 2 $25.00 hanging Davaillia fejeensis Rabbit’s Foot Fern 3 $25.00 basket Dicksonia -

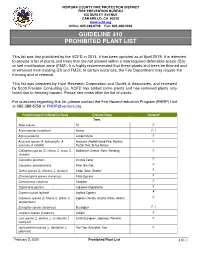

Guideline 410 Prohibited Plant List

VENTURA COUNTY FIRE PROTECTION DISTRICT FIRE PREVENTION BUREAU 165 DURLEY AVENUE CAMARILLO, CA 93010 www.vcfd.org Office: 805-389-9738 Fax: 805-388-4356 GUIDELINE 410 PROHIBITED PLANT LIST This list was first published by the VCFD in 2014. It has been updated as of April 2019. It is intended to provide a list of plants and trees that are not allowed within a new required defensible space (DS) or fuel modification zone (FMZ). It is highly recommended that these plants and trees be thinned and or removed from existing DS and FMZs. In certain instances, the Fire Department may require the thinning and or removal. This list was prepared by Hunt Research Corporation and Dudek & Associates, and reviewed by Scott Franklin Consulting Co, VCFD has added some plants and has removed plants only listed due to freezing hazard. Please see notes after the list of plants. For questions regarding this list, please contact the Fire Hazard reduction Program (FHRP) Unit at 085-389-9759 or [email protected] Prohibited plant list:Botanical Name Common Name Comment* Trees Abies species Fir F Acacia species (numerous) Acacia F, I Agonis juniperina Juniper Myrtle F Araucaria species (A. heterophylla, A. Araucaria (Norfolk Island Pine, Monkey F araucana, A. bidwillii) Puzzle Tree, Bunya Bunya) Callistemon species (C. citrinus, C. rosea, C. Bottlebrush (Lemon, Rose, Weeping) F viminalis) Calocedrus decurrens Incense Cedar F Casuarina cunninghamiana River She-Oak F Cedrus species (C. atlantica, C. deodara) Cedar (Atlas, Deodar) F Chamaecyparis species (numerous) False Cypress F Cinnamomum camphora Camphor F Cryptomeria japonica Japanese Cryptomeria F Cupressocyparis leylandii Leyland Cypress F Cupressus species (C. -

Mants Availability Shrubs

FooterDate Co ProdCategory BotPlant A2 Price1 Price2 Price3 Perennials 1 to 24 25 to 49 50 & Up Achellia fillipendulina 'Coronation Gold' 1 Gal 286.00 5.00 4.25 3.50 Achellia fillipendulina 'Coronation Gold' Flat 54.00 26.00 23.00 20.00 Achillea millefolium 'Strawberry Seduction' 1 Gal 10.00 5.00 4.25 3.50 Andropogon ternarius 1 Gal 1,422.00 5.50 4.75 4.00 Asclepias tuberosa 1 Gal 473.00 5.00 4.25 3.50 Asclepias tuberosa Flat 30.00 26.00 23.00 20.00 Aster novae-angliae 'Purple Dome' 1 Gal 1,314.00 5.00 4.25 3.50 Aster novae-angliae 'Purple Dome' Flat 34.00 26.00 23.00 20.00 Athyrium 'Ghost' 1 Gal 368.00 5.50 4.75 4.00 Calamagrostis sp. 1 Gal 242.00 5.50 4.75 4.00 Calamagrostis x acutiflora 'Karl Foerester' 3 Gal 598.00 10.75 9.50 8.25 Carex comans Marginata 'Snowline' 1 Gal 898.00 6.25 5.50 4.75 Carex hachijoensis 'Evergold' 1 Gal 926.00 6.25 5.50 4.75 Carex morrovii 'Ice Dance' 1 Gal 1,197.00 6.25 5.50 4.75 Carex pensylvanica 1 Gal 91.00 6.25 5.50 4.75 Chasmanthium latifolium 1 Gal 1,550.00 5.50 4.75 4.00 Convallaria majalis 1 Gal 17.00 5.50 4.75 4.00 Coreopsis 'Moonbeam' 1 Gal 1,326.00 5.00 4.25 3.50 Crocosmia x crocosmiiflora 'Emily McKenzie' 1 Gal 10.00 5.00 4.25 3.50 Dicentra spectabilis 3 Gal 21.00 13.50 12.00 10.00 Dryopteris marginalis 1 Gal 854.00 5.50 4.75 4.00 Echinacea 'Pow Wow White' 1 Gal 220.00 5.00 4.25 3.50 Echinacea 'Pow wow Wild Berry' 1 Gal 1,920.00 5.00 4.25 3.50 Echinacea 'Pow wow Wild Berry' 2 Gal 72.00 8.50 7.25 6.00 Echinacea 'Pow wow Wild Berry' Flat 9.00 26.00 23.00 20.00 Echinacea purpurea 1 Gal 125.00 5.00 -

Morphology and Morphogenesis of the Seed Cones of the Cupressaceae - Part II Cupressoideae

1 2 Bull. CCP 4 (2): 51-78. (10.2015) A. Jagel & V.M. Dörken Morphology and morphogenesis of the seed cones of the Cupressaceae - part II Cupressoideae Summary The cone morphology of the Cupressoideae genera Calocedrus, Thuja, Thujopsis, Chamaecyparis, Fokienia, Platycladus, Microbiota, Tetraclinis, Cupressus and Juniperus are presented in young stages, at pollination time as well as at maturity. Typical cone diagrams were drawn for each genus. In contrast to the taxodiaceous Cupressaceae, in Cupressoideae outgrowths of the seed-scale do not exist; the seed scale is completely reduced to the ovules, inserted in the axil of the cone scale. The cone scale represents the bract scale and is not a bract- /seed scale complex as is often postulated. Especially within the strongly derived groups of the Cupressoideae an increased number of ovules and the appearance of more than one row of ovules occurs. The ovules in a row develop centripetally. Each row represents one of ascending accessory shoots. Within a cone the ovules develop from proximal to distal. Within the Cupressoideae a distinct tendency can be observed shifting the fertile zone in distal parts of the cone by reducing sterile elements. In some of the most derived taxa the ovules are no longer (only) inserted axillary, but (additionally) terminal at the end of the cone axis or they alternate to the terminal cone scales (Microbiota, Tetraclinis, Juniperus). Such non-axillary ovules could be regarded as derived from axillary ones (Microbiota) or they develop directly from the apical meristem and represent elements of a terminal short-shoot (Tetraclinis, Juniperus). -

Tree Domestication and the History of Plantations - J.W

THE ROLE OF FOOD, AGRICULTURE, FORESTRY AND FISHERIES IN HUMAN NUTRITION – Vol. II - Tree Domestication and the History of Plantations - J.W. Turnbull TREE DOMESTICATION AND THE HISTORY OF PLANTATIONS J.W. Turnbull CSIRO Forestry and Forest Products, Canberra, Australia Keywords: Industrial plantations, protection forests, urban forestry, clonal forestry, forest management, tree harvesting, tree planting, monoculture, provenance, germplasm, silviculture, botanic gardens, arboreta, fuelwood, molecular biology, genetics, tropical rainforest, pulpwood, shelterbelts, rubber, pharmaceuticals, lumber, fruit trees, palm oil, Eucalyptus, farm forestry, dune stabilization, clear-cutting, religious ceremony Contents 1. Introduction 2. Origins of Planting 2.1. The Mediterranean Lands 2.2. Asia 3. Movement of Germplasm 3.1. Evidence of Early Transfers 3.2. Role of Botanic Gardens and Arboreta 3.3. Australian Tree Species and Their Transfer 3.4. North Asia as a Rich Source 4. Tree Domestication 4.1. Domestication by Indigenous Peoples 4.2. Selection and Breeding of Forest Trees 4.3. Forest Genetics 5. Plantations 6. Forest Plantations 1400–1900 6.1. European Experiences 6.2. Tropical Plantations 7. Plantations 1900–1950 8. Plantations 1950–2000 8.1. Global Overview 9. Protection Forests 10. Amenity Planting and Urban Forestry 11. Plantation Practices 11.1. TheUNESCO Mechanical Revolution – EOLSS 12. Sustainability of Plantations Glossary SAMPLE CHAPTERS Bibliography Biographical Sketch Summary Trees have been planted for thousands of years for food, wood, shelter, and religious purposes. The first woody plants to be cultivated were those yielding food, such as the olive. Trees were moved around the world by the Romans, Greeks, Chinese, and by others during military conquests. Voyages of discovery by European navigators to the ©Encyclopedia of Life Support Systems (EOLSS) THE ROLE OF FOOD, AGRICULTURE, FORESTRY AND FISHERIES IN HUMAN NUTRITION – Vol. -

The New York Botanical Garden

Vol. XV DECEMBER, 1914 No. 180 JOURNAL The New York Botanical Garden EDITOR ARLOW BURDETTE STOUT Director of the Laboratories CONTENTS PAGE Index to Volumes I-XV »33 PUBLISHED FOR THE GARDEN AT 41 NORTH QUBKN STRHBT, LANCASTER, PA. THI NEW ERA PRINTING COMPANY OFFICERS 1914 PRESIDENT—W. GILMAN THOMPSON „ „ _ i ANDREW CARNEGIE VICE PRESIDENTS J FRANCIS LYNDE STETSON TREASURER—JAMES A. SCRYMSER SECRETARY—N. L. BRITTON BOARD OF- MANAGERS 1. ELECTED MANAGERS Term expires January, 1915 N. L. BRITTON W. J. MATHESON ANDREW CARNEGIE W GILMAN THOMPSON LEWIS RUTHERFORD MORRIS Term expire January. 1916 THOMAS H. HUBBARD FRANCIS LYNDE STETSON GEORGE W. PERKINS MVLES TIERNEY LOUIS C. TIFFANY Term expire* January, 1917 EDWARD D. ADAMS JAMES A. SCRYMSER ROBERT W. DE FOREST HENRY W. DE FOREST J. P. MORGAN DANIEL GUGGENHEIM 2. EX-OFFICIO MANAGERS THE MAYOR OP THE CITY OF NEW YORK HON. JOHN PURROY MITCHEL THE PRESIDENT OP THE DEPARTMENT OP PUBLIC PARES HON. GEORGE CABOT WARD 3. SCIENTIFIC DIRECTORS PROF. H. H. RUSBY. Chairman EUGENE P. BICKNELL PROF. WILLIAM J. GIES DR. NICHOLAS MURRAY BUTLER PROF. R. A. HARPER THOMAS W. CHURCHILL PROF. JAMES F. KEMP PROF. FREDERIC S. LEE GARDEN STAFF DR. N. L. BRITTON, Director-in-Chief (Development, Administration) DR. W. A. MURRILL, Assistant Director (Administration) DR. JOHN K. SMALL, Head Curator of the Museums (Flowering Plants) DR. P. A. RYDBERG, Curator (Flowering Plants) DR. MARSHALL A. HOWE, Curator (Flowerless Plants) DR. FRED J. SEAVER, Curator (Flowerless Plants) ROBERT S. WILLIAMS, Administrative Assistant PERCY WILSON, Associate Curator DR. FRANCIS W. PENNELL, Associate Curator GEORGE V. -

Nursery Catalog

Tel: 503.628.8685 Fax: 503.628.1426 www.eshraghinursery.com 1 Eshraghi’s TOP 10 picks Our locations 1 Main Office, Shipping & Growing 2 Retail Store & Growing 26985 SW Farmington Road Farmington Gardens Hillsboro, OR 97123 21815 SW Farmington Road Beaverton, OR 97007 1 2 3 7 6 3 River Ranch Facility 4 Liberty Farm 4 5 10 N SUNSET HWY TO PORTLAND 8 9 TU HILLSBORO ALA TIN 26 VALL SW 185TH AVE. EY HWY. #4 8 BEAVERTON TONGUE LN. GRABEL RD . D R . E D G R ID E ALOHA R G B D I R R #3 SW 209TH E B T D FARMINGTON ROAD D N A I SIMPSON O O M O R R 10 217 ROSEDALE W R E S W V S I R N W O 219 T K C A J #2 #1 SW UNGER RD. SW 185TH AVE. 1 Acer circinatum ‘Pacific Fire’ (Vine Maple), page 6 D A SW MURRAY BLVD. N RO 2 palmatum (Japanese Maple), NGTO Acer 'Geisha Gone Wild' page 8 FARMI 3 Acer palmatum 'Mikawa yatsubusa' (Japanese Maple), page 10 #1 4 Acer palmatum dissectum 'Orangeola' (Japanese Maple), page 14 5 Hydrangea macrophylla 'McKay', Cherry Explosion PP28757 (Hydrangea), page 32 6 Picea glauca 'Eshraghi1', Poco Verde (White Spruce), page 61 ROAD HILL CLARK 7 Picea pungens 'Hockersmith', Linda (Colorado Spruce), page 64 RY ROAD 8 Pinus nigra 'Green Tower' (Austrian Pine), page 65 SCHOLLS FER 9 Thuja occidentalis 'Janed Gold', Highlights™ PP21967 (Arborvitae), page 70 10 Thuja occidentalis 'Anniek', Sienna Sunset™ (Arborvitae), page 69 Table of contents Tags Make a Difference . -

Supporting Information

Supporting Information Mao et al. 10.1073/pnas.1114319109 SI Text BEAST Analyses. In addition to a BEAST analysis that used uniform Selection of Fossil Taxa and Their Phylogenetic Positions. The in- prior distributions for all calibrations (run 1; 144-taxon dataset, tegration of fossil calibrations is the most critical step in molecular calibrations as in Table S4), we performed eight additional dating (1, 2). We only used the fossil taxa with ovulate cones that analyses to explore factors affecting estimates of divergence could be assigned unambiguously to the extant groups (Table S4). time (Fig. S3). The exact phylogenetic position of fossils used to calibrate the First, to test the effect of calibration point P, which is close to molecular clocks was determined using the total-evidence analy- the root node and is the only functional hard maximum constraint ses (following refs. 3−5). Cordaixylon iowensis was not included in in BEAST runs using uniform priors, we carried out three runs the analyses because its assignment to the crown Acrogymno- with calibrations A through O (Table S4), and calibration P set to spermae already is supported by previous cladistic analyses (also [306.2, 351.7] (run 2), [306.2, 336.5] (run 3), and [306.2, 321.4] using the total-evidence approach) (6). Two data matrices were (run 4). The age estimates obtained in runs 2, 3, and 4 largely compiled. Matrix A comprised Ginkgo biloba, 12 living repre- overlapped with those from run 1 (Fig. S3). Second, we carried out two runs with different subsets of sentatives from each conifer family, and three fossils taxa related fi to Pinaceae and Araucariaceae (16 taxa in total; Fig. -

Methods for Measuring Frost Tolerance of Conifers: a Systematic Map

Review Methods for Measuring Frost Tolerance of Conifers: A Systematic Map Anastasia-Ainhoa Atucha Zamkova *, Katherine A. Steele and Andrew R. Smith School of Natural Sciences, Bangor University, Bangor LL57 2UW, Gwynedd, UK; [email protected] (K.A.S.); [email protected] (A.R.S.) * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: Frost tolerance is the ability of plants to withstand freezing temperatures without unrecov- erable damage. Measuring frost tolerance involves various steps, each of which will vary depending on the objectives of the study. This systematic map takes an overall view of the literature that uses frost tolerance measuring techniques in gymnosperms, focusing mainly on conifers. Many different techniques have been used for testing, and there has been little change in methodology since 2000. The gold standard remains the field observation study, which, due to its cost, is frequently substituted by other techniques. Closed enclosure freezing tests (all non-field freezing tests) are done using various types of equipment for inducing artificial freezing. An examination of the literature indicates that several factors have to be controlled in order to measure frost tolerance in a manner similar to observation in a field study. Equipment that allows controlling the freezing rate, frost exposure time and thawing rate would obtain results closer to field studies. Other important factors in study design are the number of test temperatures used, the range of temperatures selected and the decrements between the temperatures, which should be selected based on expected frost tolerance of the tissue and species. Citation: Atucha Zamkova, A.-A.; Steele, K.A.; Smith, A.R.