Miscanthus Sinensis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Construction of High-Resolution Genetic Maps Of

Huang et al. BMC Genomics (2016) 17:562 DOI 10.1186/s12864-016-2969-7 RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Construction of high-resolution genetic maps of Zoysia matrella (L.) Merrill and applications to comparative genomic analysis and QTL mapping of resistance to fall armyworm Xiaoen Huang1†, Fangfang Wang1†, Ratnesh Singh1†, James A. Reinert1, M. C. Engelke1, Anthony D. Genovesi1, Ambika Chandra1,2 and Qingyi Yu1,3* Abstract Background: Zoysia matrella, widely used in lawns and sports fields, is of great economic and ecological value. Z. matrella is an allotetraploid species (2n =4x = 40) in the genus zoysia under the subfamily Chloridoideae. Despite its ecological impacts and economic importance, the subfamily Chloridoideae has received little attention in genomics studies. As a result, limited genetic and genomic information are available for this subfamily, which have impeded progress in understanding evolutionary history of grasses in this important lineage. The lack of a high-resolution genetic map has hampered efforts to improve zoysiagrass using molecular genetic tools. Results: We used restriction site-associated DNA sequencing (RADSeq) approach and a segregating population developed from the cross between Z. matrella cultivars ‘Diamond’ and ‘Cavalier’ to construct high-resolution genetic maps of Z. matrella. The genetic map of Diamond consists of 2,375 Single Nucleotide Polymorphism (SNP) markers mapped on 20 linkage groups (LGs) with a total length of 1754.48 cM and an average distance between adjacent markers at 0.74 cM. The genetic map of Cavalier contains 3,563 SNP markers on 20 LGs, covering 1824. 92 cM, with an average distance between adjacent markers at 0.51 cM. -

Contributions to the Life-History of Tetraclinis Articu- Lata, Masters, with Some Notes on the Phylogeny of the Cupressoideae and Callitroideae

Contributions to the Life-history of Tetraclinis articu- lata, Masters, with some Notes on the Phylogeny of the Cupressoideae and Callitroideae. BY W. T. SAXTON, M.A., F.L.S., Professor of Botany at the Ahmedabad Institute of Science, India. With Plates XLIV-XLVI and nine Figures in the Text. INTRODUCTION. HE Gum Sandarach tree of Morocco and Algeria has been well known T to botanists from very early times. Some account of it is given by Hooker and Ball (20), who speak of the beauty and durability of the wood, and state that they consider the tree to be probably correctly identified with the Bvlov of the Odyssey (v. 60),1 and with the Ovlov and Ovia of Theo- phrastus (' Hist. PI.' v. 3, 7)/ as well as, undoubtedly, with the Citrus wood of the Romans. The largest trees met with by them, growing in an un- cultivated state, were about 30 feet high. The resin, known as sandarach, is stated to be collected by the Moors and exported to Europe, where it is used as a varnish. They quote Shaw (49 a and b) as having described and figured the tree under the name of Thuja articulata, in his ' Travels in Barbary'; this statement, however, is not accurate. In both editions of the work cited the plant is figured and described as ' Cupressus fructu quadri- valvi, foliis Equiseti instar articulatis '. Some interesting particulars of the use of the timber are given by Hansen (19), who also implies that the embryo has from three to six cotyledons. Both Hooker and Ball, and Hansen, followed by almost all others who have studied the plant, speak of it as Callitris qtiadrivalvis. -

Molecular Phylogenetic Analysis of Japanese Miscanthus (Poaceae)

ISSN 1346-7565 Acta Phytotax. Geobot. 68 (2): 83–92 (2017) doi: 10.18942/apg.201703 Molecular Phylogenetic Analysis of Japanese Miscanthus (Poaceae) 1 2 3,† 2 HIDENORI NAKAMORI , MIKI TOMITA , HIROSHI AZUMA , TAKEHIRO MASUZAWA 2,* AND TORU TOKUOKA 1Graduate School of Integrated Science and Technology, Shizuoka University, Ohya, Suruga-ku, Shizuoka, 422-8529, Japan; 2Department of Biological Science, Faculty of Science, Shizuoka University, Ohya, Suruga-ku, Shizuoka, 422-8529, Japan. *[email protected] (author for corresponding); 3Department of Botany, Graduate School of Science, Kyoto University, Kitashirakawa-oiwake-cho, Sakyo-ku, Kyoto 606-8502, Japan; †Present Name & address: HIROSHI SUZUKI; Liberal arts and Sciences, Faculty of Engineering, Toyama Prefectural University, 5180 Kurokawa, Imizu-shi, Toyama 939-0398, Japan Miscanthus (Poaceae) comprises about 20 species, of which seven species and two forms occur in Japan. There is controversy whether M. condensatus is a separate species or a variety or subspecies of M. sinen- sis. To determine its taxonomic status, we conducted a molecular phylogenetic analysis using DNA se- quences of the atpB-rbcL, psbC-trnS(UGA), rpl20-rps12, trnL(UAA)-trnF(GAA), trnS(GGA)- trnT(UGU), and nuclear ITS regions, and the Adh1 gene from 31 samples of the seven Japanese species of Miscanthus. The neighbor-joining (NJ) tree based on the cpDNA sequences shows that M. condensa- tus and M. sinensis share two haplotypes, and that the nuclear ITS and Adh1 sequences of the two species are identical, making it difficult to distinguishM. condensatus from M. sinensis based on DNA sequenc- es. The evidence indicates that hybridization between the two species has proceeded rapidly, or that M. -

State of New York City's Plants 2018

STATE OF NEW YORK CITY’S PLANTS 2018 Daniel Atha & Brian Boom © 2018 The New York Botanical Garden All rights reserved ISBN 978-0-89327-955-4 Center for Conservation Strategy The New York Botanical Garden 2900 Southern Boulevard Bronx, NY 10458 All photos NYBG staff Citation: Atha, D. and B. Boom. 2018. State of New York City’s Plants 2018. Center for Conservation Strategy. The New York Botanical Garden, Bronx, NY. 132 pp. STATE OF NEW YORK CITY’S PLANTS 2018 4 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 6 INTRODUCTION 10 DOCUMENTING THE CITY’S PLANTS 10 The Flora of New York City 11 Rare Species 14 Focus on Specific Area 16 Botanical Spectacle: Summer Snow 18 CITIZEN SCIENCE 20 THREATS TO THE CITY’S PLANTS 24 NEW YORK STATE PROHIBITED AND REGULATED INVASIVE SPECIES FOUND IN NEW YORK CITY 26 LOOKING AHEAD 27 CONTRIBUTORS AND ACKNOWLEGMENTS 30 LITERATURE CITED 31 APPENDIX Checklist of the Spontaneous Vascular Plants of New York City 32 Ferns and Fern Allies 35 Gymnosperms 36 Nymphaeales and Magnoliids 37 Monocots 67 Dicots 3 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY This report, State of New York City’s Plants 2018, is the first rankings of rare, threatened, endangered, and extinct species of what is envisioned by the Center for Conservation Strategy known from New York City, and based on this compilation of The New York Botanical Garden as annual updates thirteen percent of the City’s flora is imperiled or extinct in New summarizing the status of the spontaneous plant species of the York City. five boroughs of New York City. This year’s report deals with the City’s vascular plants (ferns and fern allies, gymnosperms, We have begun the process of assessing conservation status and flowering plants), but in the future it is planned to phase in at the local level for all species. -

Seiridium Canker of Cypress Trees in Arizona Jeff Schalau

ARIZONA COOPERATIVE E TENSION AZ1557 January 2012 Seiridium Canker of Cypress Trees in Arizona Jeff Schalau Introduction Leyland cypress (x Cupressocyparis leylandii) is a fast- growing evergreen that has been widely planted as a landscape specimen and along boundaries to create windbreaks or privacy screening in Arizona. The presence of Seiridium canker was confirmed in Prescott, Arizona in July 2011 and it is suspected that the disease occurs in other areas of the state. Seiridium canker was first identified in California’s San Joaquin Valley in 1928. Today, it can be found in Europe, Asia, New Zealand, Australia, South America and Africa on plants in the cypress family (Cupressaceae). Leyland cypress, Monterey cypress, (Cupressus macrocarpa) and Italian cypress (C. sempervirens) are highly susceptible and can be severely impacted by this disease. Since Leyland and Italian cypress have been widely planted in Arizona, it is imperative that Seiridium canker management strategies be applied and suitable resistant tree species be recommended for planting in the future. The Pathogen Seiridium canker is known to be caused by three different fungal species: Seiridium cardinale, S. cupressi and S. unicorne. S. cardinale is the most damaging of the three species and is SCHALAU found in California. S. unicorne and S. cupressi are found in the southeastern United States where the primary host is JEFF Leyland cypress. All three species produce asexual fruiting Figure 1. Leyland cypress tree with dead branch (upper left) and main leader bodies (acervuli) in cankers. The acervuli produce spores caused by Seiridium canker. (conidia) which spread by water, human activity (pruning and transport of infected plant material), and potentially insects, birds and animals to neighboring trees where new Symptoms and Signs infections can occur. -

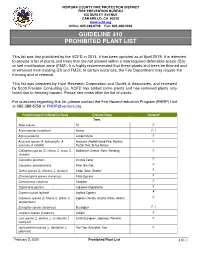

Guideline 410 Prohibited Plant List

VENTURA COUNTY FIRE PROTECTION DISTRICT FIRE PREVENTION BUREAU 165 DURLEY AVENUE CAMARILLO, CA 93010 www.vcfd.org Office: 805-389-9738 Fax: 805-388-4356 GUIDELINE 410 PROHIBITED PLANT LIST This list was first published by the VCFD in 2014. It has been updated as of April 2019. It is intended to provide a list of plants and trees that are not allowed within a new required defensible space (DS) or fuel modification zone (FMZ). It is highly recommended that these plants and trees be thinned and or removed from existing DS and FMZs. In certain instances, the Fire Department may require the thinning and or removal. This list was prepared by Hunt Research Corporation and Dudek & Associates, and reviewed by Scott Franklin Consulting Co, VCFD has added some plants and has removed plants only listed due to freezing hazard. Please see notes after the list of plants. For questions regarding this list, please contact the Fire Hazard reduction Program (FHRP) Unit at 085-389-9759 or [email protected] Prohibited plant list:Botanical Name Common Name Comment* Trees Abies species Fir F Acacia species (numerous) Acacia F, I Agonis juniperina Juniper Myrtle F Araucaria species (A. heterophylla, A. Araucaria (Norfolk Island Pine, Monkey F araucana, A. bidwillii) Puzzle Tree, Bunya Bunya) Callistemon species (C. citrinus, C. rosea, C. Bottlebrush (Lemon, Rose, Weeping) F viminalis) Calocedrus decurrens Incense Cedar F Casuarina cunninghamiana River She-Oak F Cedrus species (C. atlantica, C. deodara) Cedar (Atlas, Deodar) F Chamaecyparis species (numerous) False Cypress F Cinnamomum camphora Camphor F Cryptomeria japonica Japanese Cryptomeria F Cupressocyparis leylandii Leyland Cypress F Cupressus species (C. -

Mants Availability Shrubs

FooterDate Co ProdCategory BotPlant A2 Price1 Price2 Price3 Perennials 1 to 24 25 to 49 50 & Up Achellia fillipendulina 'Coronation Gold' 1 Gal 286.00 5.00 4.25 3.50 Achellia fillipendulina 'Coronation Gold' Flat 54.00 26.00 23.00 20.00 Achillea millefolium 'Strawberry Seduction' 1 Gal 10.00 5.00 4.25 3.50 Andropogon ternarius 1 Gal 1,422.00 5.50 4.75 4.00 Asclepias tuberosa 1 Gal 473.00 5.00 4.25 3.50 Asclepias tuberosa Flat 30.00 26.00 23.00 20.00 Aster novae-angliae 'Purple Dome' 1 Gal 1,314.00 5.00 4.25 3.50 Aster novae-angliae 'Purple Dome' Flat 34.00 26.00 23.00 20.00 Athyrium 'Ghost' 1 Gal 368.00 5.50 4.75 4.00 Calamagrostis sp. 1 Gal 242.00 5.50 4.75 4.00 Calamagrostis x acutiflora 'Karl Foerester' 3 Gal 598.00 10.75 9.50 8.25 Carex comans Marginata 'Snowline' 1 Gal 898.00 6.25 5.50 4.75 Carex hachijoensis 'Evergold' 1 Gal 926.00 6.25 5.50 4.75 Carex morrovii 'Ice Dance' 1 Gal 1,197.00 6.25 5.50 4.75 Carex pensylvanica 1 Gal 91.00 6.25 5.50 4.75 Chasmanthium latifolium 1 Gal 1,550.00 5.50 4.75 4.00 Convallaria majalis 1 Gal 17.00 5.50 4.75 4.00 Coreopsis 'Moonbeam' 1 Gal 1,326.00 5.00 4.25 3.50 Crocosmia x crocosmiiflora 'Emily McKenzie' 1 Gal 10.00 5.00 4.25 3.50 Dicentra spectabilis 3 Gal 21.00 13.50 12.00 10.00 Dryopteris marginalis 1 Gal 854.00 5.50 4.75 4.00 Echinacea 'Pow Wow White' 1 Gal 220.00 5.00 4.25 3.50 Echinacea 'Pow wow Wild Berry' 1 Gal 1,920.00 5.00 4.25 3.50 Echinacea 'Pow wow Wild Berry' 2 Gal 72.00 8.50 7.25 6.00 Echinacea 'Pow wow Wild Berry' Flat 9.00 26.00 23.00 20.00 Echinacea purpurea 1 Gal 125.00 5.00 -

Ornamental Grasses for Kentucky Landscapes Lenore J

HO-79 Ornamental Grasses for Kentucky Landscapes Lenore J. Nash, Mary L. Witt, Linda Tapp, and A. J. Powell Jr. any ornamental grasses are available for use in resi- Grasses can be purchased in containers or bare-root Mdential and commercial landscapes and gardens. This (without soil). If you purchase plants from a mail-order publication will help you select grasses that fit different nursery, they will be shipped bare-root. Some plants may landscape needs and grasses that are hardy in Kentucky not bloom until the second season, so buying a larger plant (USDA Zone 6). Grasses are selected for their attractive foli- with an established root system is a good idea if you want age, distinctive form, and/or showy flowers and seedheads. landscape value the first year. If you order from a mail- All but one of the grasses mentioned in this publication are order nursery, plants will be shipped in spring with limited perennial types (see Glossary). shipping in summer and fall. Grasses can be used as ground covers, specimen plants, in or near water, perennial borders, rock gardens, or natu- Planting ralized areas. Annual grasses and many perennial grasses When: The best time to plant grasses is spring, so they have attractive flowers and seedheads and are suitable for will be established by the time hot summer months arrive. fresh and dried arrangements. Container-grown grasses can be planted during the sum- mer as long as adequate moisture is supplied. Cool-season Selecting and Buying grasses can be planted in early fall, but plenty of mulch Select a grass that is right for your climate. -

Melatonin Influences the Early Growth Stage in Zoysia Japonica Steud. By

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Melatonin infuences the early growth stage in Zoysia japonica Steud. by regulating plant oxidation and genes of hormones Di Dong, Mengdi Wang, Yinreuizhi Li, Zhuocheng Liu, Shuwen Li, Yuehui Chao* & Liebao Han* Zoysia japonica is a commonly used turfgrass species around the world. Seed germination is a crucial stage in the plant life cycle and is particularly important for turf establishment and management. Experiments have confrmed that melatonin can be a potential regulator signal in seeds. To determine the efect of exogenous melatonin administration and explore the its potential in regulating seed growth, we studied the concentrations of several hormones and performed a transcriptome analysis of zoysia seeds after the application of melatonin. The total antioxidant capacity determination results showed that melatonin treatment could signifcantly improve the antioxidant capacity of zoysia seeds. The transcriptome analysis indicated that several of the regulatory pathways were involved in antioxidant activity and hormone activity. The hormones concentrations determination results showed that melatonin treatment contributed to decreased levels of cytokinin, abscisic acid and gibberellin in seeds, but had no signifcant efect on the secretion of auxin in early stages. Melatonin is able to afect the expression of IAA (indoleacetic acid) response genes. In addition, melatonin infuences the other hormones by its synergy with other hormones. Transcriptome research in zoysia is helpful for understanding the regulation of melatonin and mechanisms underlying melatonin- mediated developmental processes in zoysia seeds. Melatonin (MT, N-acetyl-5-methoxytryptamine), commonly known as a vertebrate neurohormone released by the pineal gland, is a tryptophan-derived metabolite. Melatonin is a versatile substance with diverse efects in various animal physiological processes. -

Tree Domestication and the History of Plantations - J.W

THE ROLE OF FOOD, AGRICULTURE, FORESTRY AND FISHERIES IN HUMAN NUTRITION – Vol. II - Tree Domestication and the History of Plantations - J.W. Turnbull TREE DOMESTICATION AND THE HISTORY OF PLANTATIONS J.W. Turnbull CSIRO Forestry and Forest Products, Canberra, Australia Keywords: Industrial plantations, protection forests, urban forestry, clonal forestry, forest management, tree harvesting, tree planting, monoculture, provenance, germplasm, silviculture, botanic gardens, arboreta, fuelwood, molecular biology, genetics, tropical rainforest, pulpwood, shelterbelts, rubber, pharmaceuticals, lumber, fruit trees, palm oil, Eucalyptus, farm forestry, dune stabilization, clear-cutting, religious ceremony Contents 1. Introduction 2. Origins of Planting 2.1. The Mediterranean Lands 2.2. Asia 3. Movement of Germplasm 3.1. Evidence of Early Transfers 3.2. Role of Botanic Gardens and Arboreta 3.3. Australian Tree Species and Their Transfer 3.4. North Asia as a Rich Source 4. Tree Domestication 4.1. Domestication by Indigenous Peoples 4.2. Selection and Breeding of Forest Trees 4.3. Forest Genetics 5. Plantations 6. Forest Plantations 1400–1900 6.1. European Experiences 6.2. Tropical Plantations 7. Plantations 1900–1950 8. Plantations 1950–2000 8.1. Global Overview 9. Protection Forests 10. Amenity Planting and Urban Forestry 11. Plantation Practices 11.1. TheUNESCO Mechanical Revolution – EOLSS 12. Sustainability of Plantations Glossary SAMPLE CHAPTERS Bibliography Biographical Sketch Summary Trees have been planted for thousands of years for food, wood, shelter, and religious purposes. The first woody plants to be cultivated were those yielding food, such as the olive. Trees were moved around the world by the Romans, Greeks, Chinese, and by others during military conquests. Voyages of discovery by European navigators to the ©Encyclopedia of Life Support Systems (EOLSS) THE ROLE OF FOOD, AGRICULTURE, FORESTRY AND FISHERIES IN HUMAN NUTRITION – Vol. -

Ornamental Grasses for the Midsouth Landscape

Ornamental Grasses for the Midsouth Landscape Ornamental grasses with their variety of form, may seem similar, grasses vary greatly, ranging from cool color, texture, and size add diversity and dimension to season to warm season grasses, from woody to herbaceous, a landscape. Not many other groups of plants can boast and from annuals to long-lived perennials. attractiveness during practically all seasons. The only time This variation has resulted in five recognized they could be considered not to contribute to the beauty of subfamilies within Poaceae. They are Arundinoideae, the landscape is the few weeks in the early spring between a unique mix of woody and herbaceous grass species; cutting back the old growth of the warm-season grasses Bambusoideae, the bamboos; Chloridoideae, warm- until the sprouting of new growth. From their emergence season herbaceous grasses; Panicoideae, also warm-season in the spring through winter, warm-season ornamental herbaceous grasses; and Pooideae, a cool-season subfamily. grasses add drama, grace, and motion to the landscape Their habitats also vary. Grasses are found across the unlike any other plants. globe, including in Antarctica. They have a strong presence One of the unique and desirable contributions in prairies, like those in the Great Plains, and savannas, like ornamental grasses make to the landscape is their sound. those in southern Africa. It is important to recognize these Anyone who has ever been in a pine forest on a windy day natural characteristics when using grasses for ornament, is aware of the ethereal music of wind against pine foliage. since they determine adaptability and management within The effect varies with the strength of the wind and the a landscape or region, as well as invasive potential. -

Supporting Information

Supporting Information Mao et al. 10.1073/pnas.1114319109 SI Text BEAST Analyses. In addition to a BEAST analysis that used uniform Selection of Fossil Taxa and Their Phylogenetic Positions. The in- prior distributions for all calibrations (run 1; 144-taxon dataset, tegration of fossil calibrations is the most critical step in molecular calibrations as in Table S4), we performed eight additional dating (1, 2). We only used the fossil taxa with ovulate cones that analyses to explore factors affecting estimates of divergence could be assigned unambiguously to the extant groups (Table S4). time (Fig. S3). The exact phylogenetic position of fossils used to calibrate the First, to test the effect of calibration point P, which is close to molecular clocks was determined using the total-evidence analy- the root node and is the only functional hard maximum constraint ses (following refs. 3−5). Cordaixylon iowensis was not included in in BEAST runs using uniform priors, we carried out three runs the analyses because its assignment to the crown Acrogymno- with calibrations A through O (Table S4), and calibration P set to spermae already is supported by previous cladistic analyses (also [306.2, 351.7] (run 2), [306.2, 336.5] (run 3), and [306.2, 321.4] using the total-evidence approach) (6). Two data matrices were (run 4). The age estimates obtained in runs 2, 3, and 4 largely compiled. Matrix A comprised Ginkgo biloba, 12 living repre- overlapped with those from run 1 (Fig. S3). Second, we carried out two runs with different subsets of sentatives from each conifer family, and three fossils taxa related fi to Pinaceae and Araucariaceae (16 taxa in total; Fig.