The 19991 Mt. Pinatubo Eruption and the Aetus of the Phillip

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

POPCEN Report No. 3.Pdf

CITATION: Philippine Statistics Authority, 2015 Census of Population, Report No. 3 – Population, Land Area, and Population Density ISSN 0117-1453 ISSN 0117-1453 REPORT NO. 3 22001155 CCeennssuuss ooff PPooppuullaattiioonn PPooppuullaattiioonn,, LLaanndd AArreeaa,, aanndd PPooppuullaattiioonn DDeennssiittyy Republic of the Philippines Philippine Statistics Authority Quezon City REPUBLIC OF THE PHILIPPINES HIS EXCELLENCY PRESIDENT RODRIGO R. DUTERTE PHILIPPINE STATISTICS AUTHORITY BOARD Honorable Ernesto M. Pernia Chairperson PHILIPPINE STATISTICS AUTHORITY Lisa Grace S. Bersales, Ph.D. National Statistician Josie B. Perez Deputy National Statistician Censuses and Technical Coordination Office Minerva Eloisa P. Esquivias Assistant National Statistician National Censuses Service ISSN 0117-1453 FOREWORD The Philippine Statistics Authority (PSA) conducted the 2015 Census of Population (POPCEN 2015) in August 2015 primarily to update the country’s population and its demographic characteristics, such as the size, composition, and geographic distribution. Report No. 3 – Population, Land Area, and Population Density is among the series of publications that present the results of the POPCEN 2015. This publication provides information on the population size, land area, and population density by region, province, highly urbanized city, and city/municipality based on the data from population census conducted by the PSA in the years 2000, 2010, and 2015; and data on land area by city/municipality as of December 2013 that was provided by the Land Management Bureau (LMB) of the Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR). Also presented in this report is the percent change in the population density over the three census years. The population density shows the relationship of the population to the size of land where the population resides. -

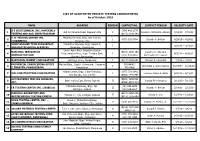

III III III III LIST of ACCREDITED PRIVATE TESTING LABORATORIES As of October 2019

LIST OF ACCREDITED PRIVATE TESTING LABORATORIES As of October 2019 NAME ADDRESS REGION CONTACT NO. CONTACT PERSON VALIDITY DATE A’S GEOTECHNICAL INC. MATERIALS (074) 442-2775 1 Old De Venecia Road, Dagupan City I Dioscoro Richard B. Alviedo 7/16/19 – 7/15/21 TESTING AND SOIL INVESTIGATION (0917) 1141-343 E. B. TESTING CENTER INC. McArthur Hi-way, Brgy. San Vicente, 2 I (075) 632-7364 Elnardo P. Bolivar 4/29/19 – 4/28/21 (URDANETA) Urdaneta City JORIZ GROUND TECH SUBSURFACE MacArthur Highway, Brgy. Surabnit, 3 I 3/20/18 – 3/19/20 AND GEOTECHNICAL SERVICES Binalonan, Pangasinan Lower Agno River Irrigation System NATIONAL IRRIGATION (0918) 8885-152 Ceferino C. Sta. Ana 4 Improvement Proj., Brgy. Tomana East, I 4/30/19 – 4/29/21 ADMINISTRATION (075) 633-3887 Rommeljon M. Leonen Rosales, Pangasinan 5 NORTHERN CEMENT CORPORATION Labayug, Sison, Pangasinan I (0917) 5764-091 Vincent F. Cabanilla 7/3/19 – 7/2/21 PROVINCIAL ENGINEERING OFFICE Malong Bldg., Capitol Compound, Lingayen, 542-6406 / 6 I Antonieta C. Delos Santos 11/23/17 – 11/22/19 (LINGAYEN, PANGASINAN) Pangasinan 542-6468 Valdez Center, Brgy. 1 San Francisco, (077) 781-2942 7 VVH CONSTRUCTION CORPORATION I Francisco Wayne B. Butay 6/20/19 – 6/19/21 San Nicolas, Ilocos Norte (0966) 544-8491 ACCURATEMIX TESTING SERVICES, (0906) 4859-531 8 Brgy. Muñoz East, Roxas, Isabela II Juanita Pine-Ordanez 3/11/19 – 3/10/21 INC. (0956) 4078-310 Maharlika Highway, Brgy. Ipil, (02) 633-6098 9 EB TESTING CENTER INC. (ISABELA) II Elnardo P. Bolivar 2/14/18 – 2/13/20 Echague, Isabela (02) 636-8827 MASUDA LABORATORY AND (0917) 8250-896 10 Marana 1st, City of Ilagan, Isabela II Randy S. -

Policy Performance Indicators at the Subnational Level

Urban Environments in Low-Income and Lower Middle-Income Countries: Policy Performance Indicators at the Subnational Level Prepared for the Millennium Challenge Corporation By Colin Christopher Rosina Estol-Peixoto Elizabeth Hartjes Angela Rampton Pamela Ritger Hilary Waukau May 18, 2012 Workshop in International Public Affairs ©2012 Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System All rights reserved. For additional copies: Publications Office La Follette School of Public Affairs 1225 Observatory Drive, Madison, WI 53706 www.lafollette.wisc.edu/publications/workshops.html [email protected] The Robert M. La Follette School of Public Affairs is a teaching and research department of the University of Wisconsin–Madison. The school takes no stand on policy issues; opinions expressed in these pages reflect the views of the authors. Table of Contents List of Tables and Figures .................................................................................. vii Foreword ............................................................................................................... ix Acknowledgments ................................................................................................ xi Executive Summary ........................................................................................... xiii Introduction ........................................................................................................... 1 I. What Do We Know About Economic Growth and Poverty in Urban Areas?.................................................................................................................... -

The Great History

CAPAS The Great History Created in 1710, Capas is among the oldest towns of Tarlac together with Bamban (1710), Paniqui (1574) and Tarlac (1686). Its creation was justified by numerous settlements which were already established in the river banks of Cutcut River since the advent of the eighteenth century. The settlements belonged to the domain of Pagbatuan and Gudya; two sitios united by Capitan Mariano Capiendo when he founded the municipality. Historical records suggest three versions on how Capas got its name. The first version, as told, was originated from capas-capas, the “edible flower” similar to that of the caturay or the melaguas that abundantly grew along the Cutcut river banks. The second version, accordingly, was adapted from a “cotton tree” called capas, in Aeta dialect. The third version suggested that it was derived from the first three letters of the surnames of the town’s early settlers, namely: Capitulo, Capitly, Capiendo, Capuno, Caponga, Capingian, Caparas, Capera, Capunpue, Capit, Capil, Capunfuerza, Capunpun, Caputol, Capul and Capan. Assertively, they were called “caps” or “capas” in the local language. Between 1946-1951, registered barangays of Capas were Lawy, O’Donnell, Aranguren, Sto. Domingo, Talaga, Sta. Lucia, Bueno, Sta. Juliana, Sampucao, Calingcuan, Dolores and Manga, which were the 12 barrios during Late President Elpidio Quirino issued the Executive Order No. 486 providing “for the collection and compilation of historical data regarding barrios, towns, cities and provinces.” Today, Capas constitutes 20 barangays including all 12 except Calingcuan was changed to Estrada, Sampucao to Maruglu, Sto. Domingo was divided in two and barangays such as Sta. -

The Struggle of the Small-Scale Fisherfolk of Masinloc and Oyon Bay for Good Governance in a Protected Seascape by Cesar Allan Vera1

The Struggle of the Small-Scale Fisherfolk of Masinloc and Oyon Bay for Good Governance in a Protected Seascape By Cesar Allan Vera1 Introduction In 1992, President Fidel Ramos visited the people of Masinloc and took a leisurely dive in the waters of Masinloc Bay. From a backdrop of live corals, a swarm of damselfish, butterflyfish, groupers, lobsters and other creatures took over the chores of welcoming the President to the beautiful waters of bay. The vision of vibrant lifeforms was awe inspiring, considering that the same water was heavily devastated by dynamite and cyanide fishing just a few years before. The turnaround in the state of the coastal waters was a result of a sanctuary set up in San Salvador Island through the help of a Peace Corp Volunteer. However, the success of the sanctuary can be credited to the determination of the residents of the island to protect and preserve their natural resources. Through a community-based coastal resource management program of the non-government organization (NGO) Haribon Foundation, the local fisherfolk organization called Samahang Pangkaunlaran ng San Salvador (SPSS), took it upon themselves to manage the marine sanctuary and reserve. Their effort was legitimized by Municipal Ordinance no. 30, series of 1988. Local government officials capitalized on the enthusiastic dive of the President by lobbying Congress to declare the Masinloc and Oyon Bay as a Protected Seascape under Republic Act 7586, the National Integrated Protected Areas System (NIPAS) Act. Several consultations and public hearings were then conducted. Eventually, Masinloc and Oyon Bay was declared as a protected seascape through Proclamation No. -

Province, City, Municipality Total and Barangay Population AURORA

2010 Census of Population and Housing Aurora Total Population by Province, City, Municipality and Barangay: as of May 1, 2010 Province, City, Municipality Total and Barangay Population AURORA 201,233 BALER (Capital) 36,010 Barangay I (Pob.) 717 Barangay II (Pob.) 374 Barangay III (Pob.) 434 Barangay IV (Pob.) 389 Barangay V (Pob.) 1,662 Buhangin 5,057 Calabuanan 3,221 Obligacion 1,135 Pingit 4,989 Reserva 4,064 Sabang 4,829 Suclayin 5,923 Zabali 3,216 CASIGURAN 23,865 Barangay 1 (Pob.) 799 Barangay 2 (Pob.) 665 Barangay 3 (Pob.) 257 Barangay 4 (Pob.) 302 Barangay 5 (Pob.) 432 Barangay 6 (Pob.) 310 Barangay 7 (Pob.) 278 Barangay 8 (Pob.) 601 Calabgan 496 Calangcuasan 1,099 Calantas 1,799 Culat 630 Dibet 971 Esperanza 458 Lual 1,482 Marikit 609 Tabas 1,007 Tinib 765 National Statistics Office 1 2010 Census of Population and Housing Aurora Total Population by Province, City, Municipality and Barangay: as of May 1, 2010 Province, City, Municipality Total and Barangay Population Bianuan 3,440 Cozo 1,618 Dibacong 2,374 Ditinagyan 587 Esteves 1,786 San Ildefonso 1,100 DILASAG 15,683 Diagyan 2,537 Dicabasan 677 Dilaguidi 1,015 Dimaseset 1,408 Diniog 2,331 Lawang 379 Maligaya (Pob.) 1,801 Manggitahan 1,760 Masagana (Pob.) 1,822 Ura 712 Esperanza 1,241 DINALUNGAN 10,988 Abuleg 1,190 Zone I (Pob.) 1,866 Zone II (Pob.) 1,653 Nipoo (Bulo) 896 Dibaraybay 1,283 Ditawini 686 Mapalad 812 Paleg 971 Simbahan 1,631 DINGALAN 23,554 Aplaya 1,619 Butas Na Bato 813 Cabog (Matawe) 3,090 Caragsacan 2,729 National Statistics Office 2 2010 Census of Population and -

Diaspora Philanthropy: the Philippine Experience

Diaspora Philanthropy: The Philippine Experience ______________________________________________________________________ Victoria P. Garchitorena President The Ayala Foundation, Inc. May 2007 _________________________________________ Prepared for The Philanthropic Initiative, Inc. and The Global Equity Initiative, Harvard University Supported by The William and Flora Hewlett Foundation ____________________________________________ Diaspora Philanthropy: The Philippine Experience I . The Philippine Diaspora Major Waves of Migration The Philippines is a country with a long and vibrant history of emigration. In 2006 the country celebrated the centennial of the first surge of Filipinos to the United States in the very early 20th Century. Since then, there have been three somewhat distinct waves of migration. The first wave began when sugar workers from the Ilocos Region in Northern Philippines went to work for the Hawaii Sugar Planters Association in 1906 and continued through 1929. Even today, an overwhelming majority of the Filipinos in Hawaii are from the Ilocos Region. After a union strike in 1924, many Filipinos were banned in Hawaii and migrant labor shifted to the U.S. mainland (Vera Cruz 1994). Thousands of Filipino farm workers sailed to California and other states. Between 1906 and 1930 there were 120,000 Filipinos working in the United States. The Filipinos were at a great advantage because, as residents of an American colony, they were regarded as U.S. nationals. However, with the passage of the Tydings-McDuffie Act of 1934, which officially proclaimed Philippine independence from U.S. rule, all Filipinos in the United States were reclassified as aliens. The Great Depression of 1929 slowed Filipino migration to the United States, and Filipinos sought jobs in other parts of the world. -

Tradename Bayad Center Name Address Town/City Province Area Region Txn Type

BAYAD CENTER TXN TYPE TRADENAME ADDRESS TOWN/CITY PROVINCE AREA REGION NAME (CICO) 13SIBLINGS 13SIBLINGS COR ANTERO SORIANO GENERAL LOGISTICS LOGISTICS HIWAY,CENTENNIAL RD. & CAVITE SOL REGION IV - A Cash in only TRIAS SERVICES SERVICES GEN TRIAS, CAVITE BAYAD CENTER - 3056 A. REDEMPTORIST 2AV PAYMENT PARAÑAQUE METRO REDEMPTORIST, ROAD, BACLARAN, GMM NCR Cash in only CENTER CITY MANILA BACLARAN PARAÑAQUE CITY 3 AJ BAYAD MASSWAY SUPERMARKET BAYAD CENTER - CENTER - BRGY BINAKAYAN, KAWIT KAWIT CAVITE SOL REGION IV - A Cash in only MASSWAY MASSWAY CAVITE 888 CASHER BLOCK 17, L17, STALL 1, BAYAD CENTER - LAS PIÑAS METRO CORPORATION - DONNA AGUIRRE AVE. PILAR, GMM NCR Cash in only PILAR VILLAGE CITY MANILA PILAR LAS PIÑAS CITY BLK 9 LOT 22 PINAGSAMA AGINAYA BAYAD CENTER - METRO VILLAGE PHASE 2, TAGUIG TAGUIG CITY GMM NCR Cash in only ENTERPRISE PINAGSAMA MANILA CITY AJM BUSINESS AJM BUSINESS PUROK 13, DAMILAG, MANOLO CENTER & I.T. CENTER & I.T. MANOLO FORTICH, BUKIDNON MIN REGION X Cash in only FORTICH SERVICES SERVICES BUKIDNON ALAINA JEM BAYAD CENTER - G/F RFC MOLINO MALL, TRAVEL RFC MOLINO BACOOR CAVITE SOL REGION IV - A Cash in only MOLINO BACOOR, CAVITE SERVICES MALL GROUND FLOOR, RUSTANS ALAINA JEM BAYAD CENTER - SUPERMARKET, VISTA MALL LAS PIÑAS METRO TRAVEL GMM NCR Cash in only EVIA EVIA, DAANG HARI ROAD, CITY MANILA SERVICES - EVIA LAS PINAS CITY GROUND FLOOR SERVICE AREA, FESTIVAL MALL, ALTERNATE BAYAD CENTER - COMMERCE AVENUE MUNTINLUP METRO REALITIES - GMM NCR Cash in only FESTIVAL MALL FILINVEST CORPORATE CITY, A CITY MANILA FESTIVAL MALL ALABANG, MUNTINLUPA CITY 1-E NOVA SQUARE QUIRINO AMZ BAYAD BAYAD CENTER - HWAY COR. -

Clark Area Municipal Development Project

Completion Report Project Number: 29082 Loan Number: 1658 August 2006 Philippines: Clark Area Municipal Development Project CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS Currency Unit – peso(s) (P) At Appraisal At Project Completion (31 October 1998) (8 November 2005) P1.00 = $0.0246 $0.0182 $1.00 = P40.60 P54.99 ABBREVIATIONS ADB – Asian Development Bank BAC – Bids and Awards Committee BCDA – Bases Conversion Development Authority CAMDP – Clark Area Municipal Development Project CDC – Clark Development Corporation CRU – community relations unit CSEZ – Clark Special Economic Zone DENR – Department of Environment and Natural Resources DILG – Department of the Interior and Local Government DPWH – Department of Public Works and Highways DOF – Department of Finance EA – Executing Agency EIRR – economic internal rate of return FIRR – financial internal rate of return GFI – government financial institution IA – Implementing Agency ICC – investment coordinating committee IEE – initial environmental examination IRA – internal revenue allotment LBP – Land Bank of the Philippines LGU – local government unit MDFO – Municipal Development Fund Office NEDA – National Economic and Development Authority O&M – operation and maintenance PAG – project advisory group PIU – project implementation unit PMO – project management office PMS – project management support PPMS – project performance monitoring system PPTA – project preparatory technical assistance PSC – project supervisory committee RRP – report and recommendation of the President SLA – subloan agreement SLF – sanitary landfill SPA – subproject agreement SWM – solid waste management TWG – technical working group NOTES (i) The fiscal year (FY) of the Government of the Philippines ends on 31 December. (ii) In this report, “$” refers to US dollars. Vice President C. Lawrence Greenwood, Jr., Operations Group 2 Director General R. Nag, Southeast Asia Department (SERD) Director S. -

Anjeski, Paul OH133

Wisconsin Veterans Museum Research Center Transcript of an Oral History Interview with PAUL ANJESKI Human Resources/Psychologist, Navy, Vietnam War Era 2000 OH 133 1 OH 133 Anjeski, Paul, (1951- ). Oral History Interview, 2000. User Copy: 1 sound cassette (ca. 84 min.); analog, 1 7/8 ips, mono. Master Copy: 1 sound cassette (ca. 84 min.); analog, 1 7/8 ips, mono. Video Recording: 1 videorecording (ca. 84 min.); ½ inch, color. Transcript: 0.1 linear ft. (1 folder). Abstract: Paul Anjeski, a Detroit, Michigan native, discusses his Vietnam War era experiences in the Navy, which include being stationed in the Philippines during social unrest and the eruption of Mount Pinatubo. Anjeski mentions entering ROTC, getting commissioned in the Navy in 1974, and attending Damage Control Officer School. He discusses assignment to the USS Hull as a surface warfare officer and acting as navigator. Anjeski explains how the Hull was a testing platform for new eight-inch guns that rattled the entire ship. After three and a half years aboard ship, he recalls human resources management school in Millington (Tennessee) and his assignment to a naval base in Rota (Spain). Anjeski describes duty as a human resources officer and his marriage to a female naval officer. He comments on transferring to the Naval Reserve so he could attend graduate school and his work as part of a Personnel Mobilization Team. He speaks of returning to duty in the Medical Service Corps and interning as a psychologist at Bethesda Hospital (Maryland), where his duties included evaluating people for submarine service, trauma training, and disaster assistance. -

Population by Barangay National Capital Region

CITATION : Philippine Statistics Authority, 2015 Census of Population Report No. 1 – A NATIONAL CAPITAL REGION (NCR) Population by Province, City, Municipality, and Barangay August 2016 ISSN 0117-1453 ISSN 0117-1453 REPORT NO. 1 – A 2015 Census of Population Population by Province, City, Municipality, and Barangay NATIONAL CAPITAL REGION Republic of the Philippines Philippine Statistics Authority Quezon City REPUBLIC OF THE PHILIPPINES HIS EXCELLENCY PRESIDENT RODRIGO R. DUTERTE PHILIPPINE STATISTICS AUTHORITY BOARD Honorable Ernesto M. Pernia Chairperson PHILIPPINE STATISTICS AUTHORITY Lisa Grace S. Bersales, Ph.D. National Statistician Josie B. Perez Deputy National Statistician Censuses and Technical Coordination Office Minerva Eloisa P. Esquivias Assistant National Statistician National Censuses Service ISSN 0117-1453 Presidential Proclamation No. 1269 Philippine Statistics Authority TABLE OF CONTENTS Foreword v Presidential Proclamation No. 1269 vii List of Abbreviations and Acronyms xi Explanatory Text xiii Map of the National Capital Region (NCR) xxi Highlights of the Philippine Population xxiii Highlights of the Population : National Capital Region (NCR) xxvii Summary Tables Table A. Population and Annual Population Growth Rates for the Philippines and Its Regions, Provinces, and Highly Urbanized Cities: 2000, 2010, and 2015 xxxi Table B. Population and Annual Population Growth Rates by Province, City, and Municipality in National Capital Region (NCR): 2000, 2010, and 2015 xxxiv Table C. Total Population, Household Population, -

(EIS) for Manila Third Sewerage Project

Public Disclosure Authorized Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) for Manila Third Sewerage Project Public Disclosure Authorized Volume 4: Annex on Septage/Sludge Disposal in Lahar Area February 11, 2005 Public Disclosure Authorized (Revised Draft) Public Disclosure Authorized Manila Water Company, Inc. Manila, Philippines ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT FOR SLUDGE/SEPTAGE-USE AS SOIL CONDITIONER FOR SUGAR CANE GROWTH IN LAHAR-LADEN AREAS Prepared by: Prepared for: 7th Floor, CLMC Building, 259-269 EDSA, Greenhills, Mandaluyong City Since 1955 in association with Metropolitan Waterworks and Sewerage System (MWSS) Ground Floor, MWSS Bldg., Katipunan Road, Balara, Quezon City Lichel Technologies, Inc. Unit 1910 Antel Global Corporate Center #3 Doña Julia Vargas Avenue Ortigas Center, Pasig City and MAIN REPORT Rm. 1021, 10/F Cityland Shaw Tower St. Francis Street cor. Shaw Blvd., Mandaluyong City TABLE OF CONTENTS CONTENTS PAGE VOLUME 1 – MAIN REPORT EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ES–1 BACKGROUND..................................................................................................................................................I ES-2 PROJECT DESCRIPTION..................................................................................................................................I ES-3 ENVIRONMENTAL BASELINE CONDITIONS .........................................................................................IV ES-4 SEPTAGE AND SLUDGE CHARACTERISTICS ........................................................................................VI ES-5