Countrymark Cooperative LLC CAB CS 08.2 Purdue University

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

E85 Stations in Indiana

E85 Stations in Indiana Retailer Location City ZIP Bellmart - BP 1302 Lincoln Way La Porte IN 46350 Bellmart - BP 14981 IN-23 Fir Rd Granger IN 46530 Bellmart - BP 395 S Huntington St Wabash IN 46992 Ceres Solutions LLP 1466 N McKinley Ave Rensselaer IN 47978 Citgo 15509 Lima Road Huntertown IN Citgo 3801 S Western Ave Marion IN Citgo - Bittersweet Bell-Mart 12495 McKinley Hwy Mishawaka IN 46545 Citgo - Brown Hen One StoP 2501 N College Ave Indianapolis IN 46205 Citgo - Corner Station 2246 W 2nd St Marion IN 46952 Citgo Smartshop 323 Sagamore Pkwy Lafayette IN 47904 Clark 2308 W 2md Street Marion IN 46952 CountryMark 2112 Indianapolis Rd Crawfordsville IN 47933 CountryMark 1010 E Waterford St Wakarusa IN 46573 CountryMark - North Central Co-oP1764 W Logansport Rd Peru IN 46970 CountryMark Bluffton 705 W Market St Bluffton IN 46714 Flex CountryMark Fountaintown 11650 N State Rd 9 Fountaintown IN 46130 County Line Travel Plaza 5126 W County Line Rd Columbia City IN 46725 Crystal Flash 545 South Rangeline Road Carmel IN 46032 Culver ExPress 203 N Main St Culver IN 46511 Elmos Higher Grounds - Lassus Handy8830 Dandy Coldwater Rd Fort Wayne IN 46825 Energy 24 766 W Main St Greensburg IN 47240 Energy Plus 24 817 W South St Lebanon IN 46052 Energy Plus 24 - Hamilton County Co-oP16222 Allisonville Rd Noblesville IN 46060 Energy Plus 24 - North Central Co-oP1820 Touby Pike Kokomo IN 46901 Energy Plus 24-North Central 1401 E. Jefferson Blvd. Mishawaka IN 46545 Excel Co-oP 1104 N 6th St Monticello IN 46960 Family Express-Crown Point S 998 S. -

2021 INPAA ER Manual

Download the Pipeline Awareness Viewer™ (PAV) app to learn about pipelines, including: Apply for PIMMA access Visit the API training center website COORDINATED RESPONSE EXERCISE Register for a pipeline safety meeting near you ® Download the NENA call intake checklist COORDINATED RESPONSE EXERCISE Download the PHMSA Emergency Response Guidebook Pipeline Safety Training For First Responders View a video about the pipeline industry How to use PAV: • Launch the app on your device. • Review the brief instructions. • Tap the SCAN button and aim your camera at this page.* • When the buttons appear, tap the lock icon to view the available content. • Tap the buttons to view important pipeline safety information. *For best results, enable Wi-Fi on your device prior to using the PAV app. EMERGENCY RESPONSE MANUAL Overview Operator Profiles Emergency Response NENA Pipeline Emergency Operations Signs of a Pipeline Release High Consequence Area Identification VIEW INTERACTIVE Pipeline Industry ER Initiatives CONTENT* Pipeline Damage Reporting Law 1.877.477.1162 • www.inpaa.org *Instructions on back 2021 Emergency Contact List Company Name Emergency Number Company Name Emergency Number Aurora Utilities .......................................................... (812) 926-2557 Natural Gas Pipeline Company of America Bainbridge Utilities .................................................... (765) 522-6238 (Kinder Morgan)........................................................ (800) 733-2490 Batesville Water & Gas Utility ....................................(812) -

Hybrid Vehicles Fuel Economy

Formerly Alternative Fuel News Clean Cities News Vol. 8 - No. 1 Official Publication of the Clean Cities Program and the Alternative Fuels Data Center Clean Cities Unveils Expanded Program Focus What is Clean Cities News? In response to feedback from Clean Since 1993, the Clean Cities Cities coordinators, Alternative Fuel March 2004 Program’s more than 80 coalitions News (AFN) has been redesigned and have steadily increased the number of refocused. Its successor, Clean Cities alternative fuel vehicles (AFVs) on our News (CCN), will more closely track the nation’s highways, with gains averag- efforts of Clean Cities coalitions and In This Issue ing around 17% in recent years. But coordinators and feature even more more can be done, and Clean Cities is program news. CCN will also cover the Clean Cities Unveils Expanded taking charge by expanding the tech- evolution of the Clean Cities Program Program Focus . 1 nologies and practices it will support as it grows to include fuel blends, as it strives to displace petroleum. idle reduction, hybrid vehicles, and What Is Clean Cities? . 2 Alternative fuels will remain the cor- fuel economy. Success Stories . 2 nerstone of Clean Cities, but, in addi- As you can see, CCN is shorter than tion, the program will now work to: Coalition News . 3 AFN. We’re trying to trim costs, while } Increase the use of fuel blends still delivering value. We’ll do that by Upcoming Events . 5 (diesel/biodiesel, ethanol/gasoline, increasing our news and supplement- EPAct Update . 5 and compressed natural gas (CNG)/ ing our print stories on the Clean Cities hydrogen), Web site, which is also undergoing a Coordinator Profile . -

Consent Decree, Countrymark Refining and Logistics;

Case 3:13-cv-00030-RLY-WGH Document 2-1 Filed 02/28/13 Page 1 of 110 PageID #: 59 IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF INDIANA EVANSVILLE DIVISION ____________________________________ ) UNITED STATES OF AMERICA ) ) and ) ) STATE OF INDIANA, ) ) Plaintiffs, ) Civil Action No. 3:13-CV-30-RLY-WGH ) v. ) ) COUNTRYMARK REFINING AND ) LOGISTICS, LLC, ) ) Defendant. ) ____________________________________) CONSENT DECREE Case 3:13-cv-00030-RLY-WGH Document 2-1 Filed 02/28/13 Page 2 of 110 PageID #: 60 TABLE OF CONTENTS I. JURISDICTION AND VENUE . 5 II. APPLICABILITY AND BINDING EFFECT . 5 III. OBJECTIVES . 7 IV. DEFINITIONS . 8 V. AFFIRMATIVE RELIEF . 13 A. NOx Emissions Reductions from the FCCU . 13 B. SO2 Emissions Reductions from the FCCU . 14 C. NSPS Applicability of the FCCU Catalyst Regenerator . 16 D. NOx Emissions Reductions from Combustion Units . 20 E. SO2 Emissions Reductions from and NSPS Applicability to Heaters and Boilers . 25 F. NSPS Applicability to the Sulfur Recovery Plant . 26 G. Emission Reductions from Flares and Control of Flaring Events . 28 H. Benzene Waste Operations NESHAP Program Enhancements . 29 I. Leak Detection and Repair Program Enhancements . 41 J. Incorporation of Consent Decree Requirements into Federally Enforceable Permits . 52 VI. EMISSION CREDIT GENERATION . 54 VII. SUPPLEMENTAL ENVIRONMENTAL PROJECTS . 56 VIII. REPORTING AND RECORDKEEPING . 59 IX. CIVIL PENALTY . 62 X. STIPULATED PENALTIES . 63 XI. NOTICE . 77 i Case 3:13-cv-00030-RLY-WGH Document 2-1 Filed 02/28/13 Page 3 of 110 PageID #: 61 XII. INFORMATION COLLECTION AND RETENTION . 80 XIII. FORCE MAJEURE . 81 XIV. RETENTION OF JURISDICTION/DISPUTE RESOLUTION . -

AFPM 2019 Refining Capacity Report

American Fuel & Petrochemical Manufacturers afpm.org AFPM United States Refining and Storage Capacity Report January 1, 2019 Published August 2019 Refining Capacity Report January 1, 2019 Locations of U.S. Refineries 2019 PADD V PADD IV PADD II PADD I PADD III Large: Over 75,000 bbl/cd Small: Under 75,000 bbl/cd AFPM: We Make Progress Refining Capacity Report January 1, 2019 AFPM United States Refining and Storage Capacity Report The enclosed statistics provide U.S. refining and storage The following table lists the total U.S. refining capacity for the capacity data as reported by the DOE Energy Information past five years: Administration in their 2019 Refinery Capacity Report. These data, along with other DOE statistics, are also available January 1 Total Capacity in electronically. (See the note at the bottom for details). This report Thousands of Barrels Per Calendar Day is also available on the AFPM website (www.afpm.org) located within the Data & Reports dropdown menu at the top of the 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019 webpage by clicking the Data & Statistics link. U.S. Capacity 17,967 18,317 18,617 18,598 18,802 On January 1, 2019, there were 135a operable refineries in the United States with total crude distillation capacity of about 18.80 million barrels per calendar day (bbl/cd) and 19.96 Percentage Change in U.S. Capacity from million barrels per stream day (bbl/sd). Of these, 132 refineries Previous Year were operating on January 1, 2019, with operating capacity listed at 18.69 million bbl/cd and 19.83 million bbl/sd. -

1 United States District Court Southern District Of

Case 1:16-cv-00972-SEB-MPB Document 1 Filed 04/29/16 Page 1 of 16 PageID #: 1 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF INDIANA INDIANAPOLIS DIVISION COUNTRYMARK REFINING ) AND LOGISTICS, LLC, ) an Indiana limited liability company ) ) Plaintiff, ) ) v. ) Case No. 1:16-cv-972 ) COOP FUELS INC., ) a Colorado corporation ) ) Defendant. ) COMPLAINT AND JURY DEMAND For its Complaint against Defendant COOP Fuels Inc. (“Defendant”), Plaintiff Countrymark Refining and Logistics, LLC (“Countrymark”), through the undersigned, states and alleges as follows: NATURE OF THE ACTION 1. This is an action for direct and contributory trademark infringement, false designation of origin, and unfair competition arising under the Lanham Act, 15 U.S.C. § 1051 et seq., and the statutes and common law of the State of Indiana. THE PARTIES 2. Countrymark is an Indiana limited liability company with its principal place of business in Indianapolis, Indiana. 3. Defendant is a Colorado corporation with its principal place of business in Morrisville, North Carolina. 1 US.106163539.01 Case 1:16-cv-00972-SEB-MPB Document 1 Filed 04/29/16 Page 2 of 16 PageID #: 2 JURISDICTION AND VENUE 4. This Court has subject matter jurisdiction pursuant to 28 U.S.C. §§ 1331 and 1338(a) and 15 U.S.C. § 1121(a) because Countrymark’s claims arise under the Lanham Act. 5. This Court has supplemental jurisdiction over Countrymark’s Indiana state law and common law claims pursuant to 28 U.S.C. §§ 1338(b) and 1367(a) because those claims are joined with substantial and related claims under the Lanham Act, and are so related to the claims under the Lanham Act that they form part of the same case or controversy under Article III of the United States Constitution. -

The Oil and Gas Industry in the Illinois Economy

The Oil and Gas Industry In the Illinois Economy Prepared for the Illinois Oil and Gas Association Under a grant from the Illinois Petroleum Resources Board By RCF Economic & Financial Consulting, Inc. 333 N. Michigan Ave., Suite 804 Chicago, IL 60601 & Regional Economics Applications Laboratory (REAL) University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign March 4, 2009 Table of Contents Executive Summary........................................................................................................... i 1. Introduction.................................................................................................................. 1 2. Overview of Oil and Gas Production in Illinois ........................................................ 2 2.1 Current Oil Production and the Illinois Basin............................................ 2 2.2 Historical Perspective .................................................................................... 3 2.3 Geographic Distribution................................................................................ 4 2.4 Illinois Basin Oil Reserves............................................................................. 6 2.5 Oil Wells.......................................................................................................... 7 2.6 The Industry in National Perspective .......................................................... 9 3. Ownership and Employment .................................................................................... 11 3.1 Upstream Employment and Firm Ownership.......................................... -

Fuel Contracting Countrymark Fuels and Lubricants

TRANSPORT DEF Fuel Contracting Retail service stations, commercial sites Blue DEF Diesel Exhaust Fluid is a The SynEnergy Price Risk Management / Hedging or other delivery, we have the experience mixture of high purity synthetic urea and Program is a contractual agreement that allows our to handle the load professionally. We also deionized water that is approved for use fuel customers to lock in fuel prices for a specific offer daily fuel price quotes for all of your in all diesel Selective Catalytic Reduction period of time, helping them minimize fuel price risk transport fuels. (SCR) Systems. Certified by the American and better manage their fuel budget to control energy Petroleum Institute. Made from high purity costs. TANKWAGON urea and deionized water. SynEnergy will provide you with a tank, Because we understand that all of our customers pump, filter, hose & nozzle and keep your LP GAS DELIVERY have unique energy needs, our fuel contracting Whether for home heat, farm use or tank full. Our well trained and experienced program doesn’t follow a one-size fits all approach. commercial use, trust our team to reliably Petroleum Sales Representatives will Contracting is ideal for customers with both large deliver the LP gas you need. We offer maintain and service your tanks. and small scale fuel needs. budget plans, summer fill program and You pick the fuel amount a program where you can prepay at You pick the contract period WET HOSING summer fill prices. Prefer not to have a fuel tank on your You pick the delivery schedule property? Let us come to you and fill your ADVANTAGE LUBES – LUBE SCANS Let us monitor the markets and take the gueswork fleet directly from our tankwagon. -

TEXAS TEA, Brewed in Indiana Home-Grown Oil Production Is on the Rise

A 40-foot drilling rig run by Magnum Drilling Services of Evansville and financed by CountryMark drives pipe at a location east of Terre Haute. Nearby, a CountryMark parcel produces 800 barrels a day during one year, about $30 million worth of oil. 26 March/April 2014 n OutdoorIndiana.org TEXAS TEA, brewed in Indiana Home-grown oil production is on the rise OutdoorIndiana.org n March/April 2014 27 28 March/April 2014 n OutdoorIndiana.org By Nick Werner Photography by Frank Oliver he tower of pipes, pulleys and hydraulic hoses rose 40 feet into a clear summer sky. At the base of the drilling rig, a driller and two rigT hands operated the contraption, each dressed in white hard hats and fire-resistant work shirts. The rig’s owner, Danny Veeck of Magnum Drilling Services, mon- itored progress as he stood by his heavy-duty pickup. “We are about 82 feet deep,” he told three onlook- ers, including a representative from CountryMark, the oil company financing the effort. As the hole grew deeper, the rig hands swung ad- ditional 30-foot sections of drill pipe into place. The plan was to drill a well 1,400 feet deep in this soybean field east of Terre Haute. Since 2011, a (Left) Rodney Clark prepares another 30-foot section of neighboring parcel with about a dozen wells had pro- drilling pipe to be driven into the ground by Magnum. duced 800 barrels a day for CountryMark, or about (Above) Danny Veeck of Magnum sifts through water $30 million worth of oil annually, constituting the runoff during drilling east of Terre Haute. -

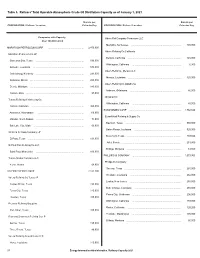

Table 5. Refiners' Total Operable Atmospheric Crude Oil Distillation Capacity As of January 1, 2021

Table 5. Refiners' Total Operable Atmospheric Crude Oil Distillation Capacity as of January 1, 2021 Barrels per Barrels per CORPORATION / Refiner / Location Calendar Day CORPORATION / Refiner / Location Calendar Day Companies with Capacity Valero Ref Company Tennessee LLC Over 100,000 bbl/cd .............................................................................................................................. Memphis, Tennessee 180,000 ..............................................................................................................................MARATHON PETROLEUM CORP 2,870,000 Valero Refining Co California Marathon Petroleum Co LP .............................................................................................................................. Benicia, California 145,000 .............................................................................................................................. Galveston Bay, Texas 593,000 .............................................................................................................................. Wilmington, California 6,300 .............................................................................................................................. Garyville, Louisiana 578,000 Valero Refining - Meraux LLC .............................................................................................................................. Catlettsburg, Kentucky 291,000 ............................................................................................................................. -

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 14

EPC EXHIBIT 1.0 Page 1 of 6 OFFfC!AU Ff& 1 PREP-D DmCT 2 OF L. S. LETNER 3 ON BEHALF OF 4 EQaON PIPELINE COMPAN%%B@ -’ 5 DOCKET NOS. 00-0462 & oo-oj$@ ~‘-.-~---------A- 6 E;e,-ar-& c 7 Ql. State your name, position and business address. 8 Al. My name is L.S. Letner and I am employed by Equilon Pipeline Company LLC as the 9 BusinessDevelopment Manager. My businessaddress is 777 Walker Street, Houston, Texas 10 77002. 11 Q2. How long have yoyouserved in t~hiscapacity with Equilon Pipeline Company LLC? 12 A2. I have served in my current position for thirteen months, and for two and one-half years in 13 similar capacity. I have a combined twenty years of pipeline experience in the Shell and 14 Equilon organizations. 15 Q3. Please describe your current duties in this position. 16 A3. My current duties include assisting in the development and negotiation of commercial 14 opportunities including optimization or divestiture of existing assets, construction or 18 acquisition of new facilities. 19 Q4. Have you testified before? 20 A4. No. 21 QS. Please summarize your educational and professional experience. 22 A5. I was awarded a Bachelor of Science degree in Mechanical Engineering from Iowa State 23 University in 1981. Since joining Shell Pipe Line, in June 1981, I have held various 24 technical, health, safety, and environmental and commercial positions as individual 25 contributor and manager. EPC EXHIBIT 1.O Page 2 of 6 26 Q6. What is the purpose of your testimony in this proceeding? 27 A6. -

COUNTRYMARK VOLUME 16, ISSUE 1 E M I Capital Idea Countrymark Is Meeting New Fuel Quality

COUNTRYMARK VOLUME 16, ISSUE 1 E M I Capital Idea CountryMark is meeting new fuel quality demands after completing a capital • Indianapolis improvement project. “It gives us the opportunity to make products we couldn’t make before and allows us to adjust or raise the severity of our product.” // PAT WARD, VICE PRESIDENT OF OPERATIONS CountryMark’s new reactor is pictured in the middle; it was part of the $80 million investment in its Mt. Vernon, Ind., refinery. [ BY KAT ZEMAN ] refinery in Mt. Vernon, Ind. The refin- to convert the high-boiling, high-molec- After making a major capital invest- ery is fitted to process roughly 30,000 ular-weight hydrocarbon fractions of ment into its oil refinery, CountryMark barrels per day of light sweet crude petroleum crude oils into more valuable has created the flexibility to meet its oil, much of which comes from the gasoline, diesel and other products. customers’ changing product demands. Illinois Basin, a series of small oilfields “Replacing the reactor allows us to The Indianapolis-based company in southeastern Illinois, southwestern run at a much higher temperature and invested roughly $80 million into its oil Indiana and western Kentucky. The severity,” says Pat Ward, vice president largest part of the capital improvement of operations. “That’s the way we de- project involved replacing a reactor scribe how much high-value products PROFILE in its fluid catalytic cracking units we can make. The reactor is the heart (FCCU), one of the refinery’s nine pro- of the unit.” CountryMark cessing units. The reactor takes oil heavier than www.countrymark.com | Headquarters: The FCCU is one of the most im- diesel but lighter than asphalt and con- Indianapolis | Employees: 470+ | Specialty: Oil portant conversion processes used in verts it into a high-value product like exploration and production petroleum refineries.