Art, Capital of the Twenty-First Century Aude Launay

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Conspiracy Lecture V2, ROTTERDAM, Curated by Stephen Kovats

Conspiracy Lecture V2, ROTTERDAM, curated by Stephen Kovats Introduction by Stephen Kovats TANGENT_CONSPIRACY V2_Institute for the Unstable Media 20.00, Friday, December 01, 2006 www.v2.nl Long before a clandestine military-academic collaboration created the 1960's ARPANET the speculative mechanisms of conspiracy theories have fueled global events. The internet and it's growing Web 2.0 counterpart have moved beyond the realm of information exchange and redundancy to become the real-time fora of narrative construction. Fuelling and fanning all forms of popular speculation the net now creates its own post-modern mythologies of world domination, corporate control and government induced fear fetishism. If the net itself is not a conspirative construct designed to control and influence global intellectual expression then, rumour has it, it plays the central role in implying as much. Has the internet now become a self-fullfiling prophecy of its own destructive speculation? V2_, in collaboration with the Media Design group of the Piet Zwart Institute, invites you to join Florian Cramer, Claudia Borges, Hans Bernhard and Alessandro Ludovico in an evening of net-based conspiracy built upon abrasive speculation, conjectural divination and devious webbots. ------------------ Alessandro Ludovico, editor in chief of Neural, has been eavesdropped upon electronically for most of his life due to his hacktivist cultural activities. Promoting cultural resistance to the pervasiveness of markets, he is an active supporter of ideas and practices that challenge the flatness of capitalism through self-organized cooperation and cultural production. Since 2005 he has been collaborating with Ubermorgen and Paolo Cirio in conceptually conspiring against the smartest marketing techniques of major online corporations. -

Leaving Reality Behind Etoy Vs Etoys Com Other Battles to Control Cyberspace By: Adam Wishart Regula Bochsler ISBN: 0066210763 See Detail of This Book on Amazon.Com

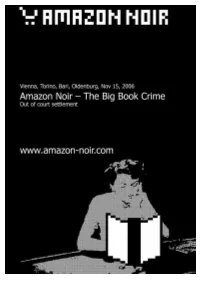

Leaving Reality Behind etoy vs eToys com other battles to control cyberspace By: Adam Wishart Regula Bochsler ISBN: 0066210763 See detail of this book on Amazon.com Book served by AMAZON NOIR (www.amazon-noir.com) project by: PAOLO CIRIO paolocirio.net UBERMORGEN.COM ubermorgen.com ALESSANDRO LUDOVICO neural.it Page 1 discovering a new toy "The new artist protests, he no longer paints." -Dadaist artist Tristan Tzara, Zh, 1916 On the balmy evening of June 1, 1990, fleets of expensive cars pulled up outside the Zurich Opera House. Stepping out and passing through the pillared porticoes was a Who's Who of Swiss society-the head of state, national sports icons, former ministers and army generals-all of whom had come to celebrate the sixty-fifth birthday of Werner Spross, the owner of a huge horticultural business empire. As one of Zurich's wealthiest and best-connected men, it was perhaps fitting that 650 of his "close friends" had been invited to attend the event, a lavish banquet followed by a performance of Romeo and Juliet. Defiantly greeting the guests were 200 demonstrators standing in the square in front of the opera house. Mostly young, wearing scruffy clothes and sporting punky haircuts, they whistled and booed, angry that the opera house had been sold out, allowing itself for the first time to be taken over by a rich patron. They were also chanting slogans about the inequity of Swiss society and the wealth of Spross's guests. The glittering horde did its very best to ignore the disturbance. The protest had the added significance of being held on the tenth anniversary of the first spark of the city's most explosive youth revolt of recent years, The Movement. -

Hans Bernhard, UBERMORGEN.COM Digital Actionism - Media Hacking (1994–2006)

Hans Bernhard, UBERMORGEN.COM Digital Actionism - Media Hacking (1994–2006) "Maverick Austrian businessman." CNN Media Hacking Media Hacking is generally described very vaguely as manipulation of media technology. A more specific definition is the massive intrusion into mass media channels with standard technology such as email or mobile communications, mobile phones, etc... Usually these actions are carried out within the legal realm - or at least in the twilight zone of international law. Sometimes laws have to be challenged in order to update/optimize the legal system. We have to judge for ourselves whether its unethical to do so or its totally reasonable to put freedome of speech above an applieable law. With such a cybernetic modus operandi – in the end only courage, intelligence and basic technological know how is necessary – we can achieve enormous reach and frequency in this age of the totally networked space. Popular media hacking projects are the „Toywar“ by etoy and „Vote-auction“ by UBERMORGEN.COM. Important to note: All our projects are non- ideological, non-political. they are pure basic research experiments. Digital Actionism digital actionism describes the intuitive transposition of the principles of actionism into the digital. The created identities – corporate and collective – become the artistic field of expression and extreme forms of aestehtics – for example pure communication. The actions are documented by media coverage, emails and logfiles. The „hanging inside the network“, to be connected to millions and millions of invisible channels, the sensation of beeing a thin membrane within a mass meda storm... thats where it happens. Playground is the body of the „Actionist“ and especially the Head. -

Where Are We Now? Contemporary Art | the Collection & Usher Gallery

Where are we now? Contemporary Art | The Collection & Usher Gallery Where are we now? 14th September – 12th January 2014 how do we find our way? Starting with a reproduction of the oldest map in our collection (the original is too delicate too have on display ) this show presents historic maps and plans alongside four artists who use as their ma- terials, not paint nor pencil, but modern mapping technology. All four artists utilise these technologies to produce art works that tell us more than the data or information alone. Justin Blinder creates visualisations of the Wi-Fi hotspots in New York, allowing us to see the concentration of wireless Internet access. As this information seems to map the city, it allows us to question if we fully understand the future benefits, or negative aspects of this wireless technology. Paolo Cirio takes images captured on Google Street View of people going about their everyday business, prints them life size and plac- es them back into the locations they were photographed. Making us face the fact that our images are being captured daily without our knowledge. How many clues do you think you left behind today? Brian House takes data from mapping devices and uses them as a base to transform the information into a new format. In these works he has used G.P.S. from a mobile phone and black box re- corders from a crash scene to score musical arrangements. Jon Rafman trawls Google Earth to locate his images, ranging from the whimsical, romantic landscape to the capturing of crimes and everything in between. -

With His Public Intervention Overexposed, Artist Paolo Cirio Disseminates Unauthorized Pictures of High-Ranking U.S

With his public intervention Overexposed, artist Paolo Cirio disseminates unauthorized pictures of high-ranking U.S. intelligence officials throughout major cities. Cirio obtained snapshots of NSA, CIA, and FBI officers through social media hacks. Then, using his HD Stencils graffiti technique, he spray-paints high-resolution reproductions of the misappropriated photos onto public walls. New modes of circulation, appropriation, contextualization, and technical reproduction of images are integrated into this artwork. The project considers the aftermath of Edward Snowden’s revelations and targets some of the officials responsible for programs of mass surveillance or for misleading the public about them. The dissemination of their candid portraits as graffiti on public walls is a modern commentary on public accountability at a time of greater demand for transparency with regard to the over- classified apparatuses of surveillance that are threatening civil rights worldwide. The officials targeted in the Overexposed series are Keith Alexander (NSA), John Brennan (CIA), Michael Hayden (NSA), Michael Rogers (NSA), James Comey (FBI), James Clapper (NSA), David Petraeus (CIA), Caitlin Hayden (NSC), and Avril Haines (NSA). In this exhibition, NOME presents the nine subjects of the Overexposed series painted on canvas and photographic paper. As a form of creative espionage, and utilizing common search engines, social engineering, as well as hacks on social media, Cirio tracked down photographs and selfies of government officials taken in informal situations. All of the photos were taken by individuals external to the intelligence agencies, by civilians or lower ranking officers. Dolziger st. 31 10247 Berlin | Tuesday - Saturday 2 PM - 6 PM Indeed, the omnipresence of cameras and the constant upload of data onto social media greatly facilitate the covert gathering of intelligence that can potentially be used in a work of art. -

The Trilogy Face-To Facebook, Smiling in the Eternal Party

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Sydney eScholarship THE HACKING MONOPOLISM servers. With the money we got we porting all the 250,000 profiles. Users TRILOGY automatically bought Google shares, so trying to contact them ended up at their Alessandro Ludovico, Neural, Bari, we were able to potentially buy Google respective Facebook public profiles. Italy, E-mail: <[email protected]>. via its own advertisements. By Paolo Cirio, Brooklyn, USA, E-mail: establishing this auto-cannibalistic The trilogy <[email protected]>. model, we deconstructed the new We found a significant conceptual hole advertisement mechanisms by rendering in all of these corporate systems and we Abstract them into a surreal click-based economic used it to expose the fragility of their The three artworks of the Hacking Monopolism model. omnipotent commercial and marketing Trilogy are Face to Facebook [1], Amazon Noir [2] In Amazon Noir, Amazon.com's web- strategies. In fact, all these corporations and GWEI-Google Will Eat Itself [3]. These works have much in common in terms of both site was the vulnerable target. We eluded established a monopoly in their methodologies and strategies. They all use custom their copyright protection with a sophis- respective sectors (Google, search programmed software to exploit three of the biggest ticated hack of the ‘Search Inside the online corporations, deploying conceptual hacks engine; Amazon, book selling; that generate unexpected holes in their well-oiled book’ service: by searching the first sen- Facebook, social media), but despite marketing and economic system. All three projects tence of a book we obtained the begin- that, their self-protective strategies are were ‘Media Hack Performances’ that exploited ning of the second sentence, and then by security vulnerabilities of the internet giants' not infallible. -

Press Release - 10 Feb

Press Release - 10 Feb. 2017. Berlin. Paolo Cirio’s artworks on view at Berlin’s photography museums. Paolo Cirio’s artworks will be on view in two upcoming major exhibitions at the C/O Berlin and Museum für Fotografie. Both of his series reflect on surveillance and privacy by combining photography, Internet and street art. Street Ghosts will be installed inside and outside the Museum für Fotografie with four artworks on its facade and entrance. Photos of individuals appropriated from Google Street View are affixed at the exact physical spot from where they were taken on Jebensstraße 2, 10623 Berlin. https://paolocirio.net/work/street-ghosts Overexposed will be presented at the C/O Museum with three framed works painted on photo paper combined with several street art posters. The large installation at Amerika Haus will present unauthorized selfies and photos of Keith Alexander (NSA), John Brennan (CIA), and James Comey (FBI). https://paolocirio.net/work/hd-stencils/overexposed You are invited to Watching You, Watching Me. A Photographic Response to Surveillance at the Museum für Fotografie (February 17 – July 2, 2017) and Watched! Surveillance Art & Photography at C/O Berlin (February 18 – April 23, 2017). http://www.co-berlin.org/watched-surveillance-art-photography-0 http://www.smb.museum/museen-und-einrichtungen/museum-fuer-fotografie/ueber-uns/nachrichten/detail/museum-fuer- fotografie-und-co-berlin-praesentieren-ab-februar-2017-erstmals-drei-inhaltlich-aufeina.html Cirio’s unique photo practice corresponds precisely to the approaches of these two shows that tackle and investigate the social and political trajectories of surveillance in correlation with art photography. -

Overexposed-Project

Overexposed Profiles and photos of Overexposed artwork series. Research assembled by Paolo Cirio, 2014-2015. http://paolocirio.net/work/hd-stencils/overexposed Keith Alexander Keith seems excited for this selfie taken by Corrie Becker, a mysterious acquaintance of his whom he shares no apparent social connection with. He has his neck tucked into his collar and an awkward smile plastered across his face. He and Corrie appear to be close and intimate, having fun with the selfie. The location where this photo was taken and how these two met each other is unclear. Corrie stated on her Facebook post, “Look who takes a great #Selfie - General Keith Alexander, the Cowboy of the NSA.” The photo was obtained from Facebook via Corrie Becker's account. Dated May 27th, 2014.1 Keith Brian Alexander served as Director of the National Security Agency (NSA) until 2013 and is now a retired four-star general. He was also Chief of the Central Security Service (CHCSS) and Commander of the U.S. Cyber Command. Alexander held key staff assignments as Deputy Director, Operations Officer, and Executive Officer both in Germany and during the Persian Gulf War in Operation Desert Shield and Operation Desert Storm. He also served in Afghanistan on a peacekeeping mission for the Army Deputy Chief of Staff for Intelligence. In Saudi Arabia he presided over the Navy’s 10th Fleet, the 24th Air Force, and the Second Army. Among the units under his command were the military intelligence teams involved in torture and prisoner abuse at Baghdad’s Abu Ghraib prison.2 Two years later, Donald Rumsfeld appointed Alexander director of the NSA. -

Media Monopoly By: Ben H Bagdikian ISBN: 0807061875 See Detail of This Book on Amazon.Com

The New Media Monopoly By: Ben H Bagdikian ISBN: 0807061875 See detail of this book on Amazon.com Book served by AMAZON NOIR (www.amazon-noir.com) project by: PAOLO CIRIO paolocirio.net UBERMORGEN.COM ubermorgen.com ALESSANDRO LUDOVICO neural.it Page 1 Senator Byron Dorgan, Democrat of North Dakota, had a potential disaster in his district when a freight train carrying anhydrous ammonia derailed, releasing a deadly cloud over the city of Minot. When the emergency alert system failed, the police called the town radio stations, six of which are owned by the corporate giant, Clear Channel. According to news accounts, no one answered the phone at the stations for more than an hour and a half Three hundred people were hospitalized, some partially blinded by the ammonia . Pets and livestock were killed. Anhydrous ammonia is a popular fertilizer that also creates a noxious gas, irritating the respiratory system and burning exposed skin. It fuses clothing to the body and sucks moisture from the eyes. To date, one person has died and 40o have been hospitalized. -HTTP://WWW.UCC.ORG/UCNEWS/MAYO2/TRAIN. HTM Clear Channel is the largest radio chain in the United States. It owns 1,240 radio stations with only Zoo employees. Most of its stations, including the six in Minot, N. Dak., are operated nationwide by remote control with the same prerecorded material.' Page 2 THE NEW MEDIA MONOPOLY The United States, as said so often at home with pride and abroad with envy or hostility, is the richest country in the world. A nation of nineteen thousand cities and towns is spread across an entire continent, with the globe's most diverse population in ethnicity, race, and country of origin. -

Catalog Evidentiary Realism

INDEX Preface 1 Evidentiary Realism by Paolo Cirio. 3 Comparison of 3 Art Exhibition Visitors’ Profles by Hans Haacke. 15 The Chase Advantage by Hans Haacke. 17 The Location of Power by Lauren van Haaften-Schick. 19 Mary Carter Resorts Study by Mark Lombardi. 31 George W. Bush, Harken Energy, and Jackson Stephens, by Mark Lombardi. 33 Edges of Evidence: Mark Lombardi‘s Drawings by Susette Min. 35 I Thought I was seeing Convicts by Harun Farocki. 45 I Thought I Was Seeing...by Jaroslav Anděl. 47 THE WHITE HOUSE 2002 GREEN WHITE by Jenny Holzer. 57 Can We See Torture? by Joshua Craze. 60 The Video Diaries by Khaled Hafez. 67 The Magma of Reality by Nicola Trezzi. 69 Mengele’s Skull by Thomas Keenan and Eyal Weizman. 75 How to Make a Face Appear: The Case of Mengele’s Skull by Heather Davis. 77 Monsanto Intervention by Kirsten Stolle. 83 Chemical Interventions by Mary Anne Redding. 85 Camoufage by Suzanne Treister. 93 Rendering the Evidence by Giulia Bini. 95 Information of Note by Josh Begley. 101 The Eye of the Law by Nijah Cunningham. 103 The Other Nefertiti by Nora Al-Badri and Jan Nikolai. 111 Conficting Evidence by Susanne Leeb. 113 Seamless Transitions by James Bridle. 121 Infrastructural Violence: The Smooth Spaces of Terror by Susan Schuppli. 123 Reconnaissance by Ingrid Burrington. 131 Crucial Nodes Designed to be Ignored by Aude Launay. 133 A People’s Archive of Sinking and Melting by Amy Balkin. 141 An Archive of Evidence by Blanca de la Torre. 143 Expanding and Remaining by Navine G. -

Picture As Pdf

1 Cultural Daily Independent Voices, New Perspectives Interlock: The Essential Mark Lombardi Patricia Goldstone · Thursday, October 20th, 2016 [alert type=alert-white ]Please consider making a tax-deductible donation now so we can keep publishing strong creative voices.[/alert] Before Edward Snowden, before Julian Assange, and long before an international consortium of 400 journalists broke the story of an 11-million tax-scam document leak they called the Panama Papers, there was Mark Lombardi, a lone conceptual artist who drew a continual visual history of the offshore banking business before he was found hanged in his 300 square-foot Williamsburg studio at the age of 49. The Panama Papers are only a part of the alternative world economy Lombardi mapped in a monumental series of elegant visual narratives detailing marriages of convenience between intelligence agencies, governments, corporations (i.e. banks) and organized crime from the 1930s to the year 2000, when he died. Connecting his drawings to form a 360-degreee panorama, he described the evolution of a single network which has consumed the financial ecology over time in a series of related bubbles, one of which predicts the next. Because he meticulously used both legal and mathematical tools to compose his drawings—with principles of proportional beauty he appropriated from Leonardo Da Vinci – Lombardi straddles the cusp between art and information, the first artist to “do metadata”. He is certainly the first artist to be studied in depth by the intelligence agencies he scrutinized in his work, and whose legacy is a financial fraud investigation platform, created by Peter “PayPal” Thiel with venture capital from the CIA. -

Die Öffentlichkeit Der Verschwörung. Ästhetik Und Politische Ökonomie Bei Mark Lombardi 2012

Repositorium für die Medienwissenschaft Sebastian Gießmann Die Öffentlichkeit der Verschwörung. Ästhetik und politische Ökonomie bei Mark Lombardi 2012 https://doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/1929 Veröffentlichungsversion / published version Sammelbandbeitrag / collection article Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: Gießmann, Sebastian: Die Öffentlichkeit der Verschwörung. Ästhetik und politische Ökonomie bei Mark Lombardi. In: Dietmar Kammerer (Hg.): Vom Publicum. Das Öffentliche in der Kunst. Bielefeld: transcript 2012, S. 29– 47. DOI: https://doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/1929. Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer Creative Commons - This document is made available under a creative commons - Namensnennung - Nicht kommerziell - Keine Bearbeitungen 3.0 Attribution - Non Commercial - No Derivatives 3.0 License. For Lizenz zur Verfügung gestellt. Nähere Auskünfte zu dieser Lizenz more information see: finden Sie hier: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0 Die Öffentlichkeit der Verschwörung. Ästhetik und politische Ökonomie bei Mark Lombardi* SEBASTIAN GIESSMANN Es erscheint zwar verwegen, liegt aber auf der Hand: Revolution, De- mokratie und Strukturwandel der Öffentlichkeit brauchen Gerüchte und Verschwörungen wie die Luft zum Atmen. So zeichneten sich die antiken Athener nicht nur durch ihre Streitfreude vor Gericht oder ihre Theaterleidenschaft aus, sondern ebenso durch eine enorme Lust am politischen Frondieren.1 Ob diese, wie wir aus der Mediengeschichte der Verschwörungstheorie zu wissen meinen,2 erst mit der frühneuzeit- lichen und aufklärerischen Öffentlichkeit wiederkehrt, wäre eine Fra- ge, die Mediävistik und transnationale Geschichtsschreibung beant- worten müssten. Ich orientiere mich hingegen im Folgenden aber an jener Öffentlichkeit, deren historische Formation man in Büchern wie * Der für diesen Band bearbeitete und durchgesehene Text ist in erweiterter Form ebenfalls erschienen in: Krause, Markus/Meteling, Arno/Stauff, Mar- kus: Parallax View.