Profiting from Abuse

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Frequently Asked Questions

FREQUENTLY ASKED QUESTIONS About the Sex Industry in Thailand Is prostitution legal in Thailand? Prostitution is NOT legal in Thailand. However, due to the billions of dollars it feeds into the country’s tourism industry, prostitution is being considered for legalization. Where do women in prostitution in Thailand come from? The majority of Thai women migrating to Bangkok to work in prostitution are from rice farming areas in Northeast Thailand. The majority of women we see being trafficked into Thailand from other countries are coming from Eastern Europe, Africa, and South America. How old are most of the women? The age range of Thai women working in the bars is between 17 and 50 years old. The average age is around 27. Although the legal age to work in a bar is 18, many girls start at 17. Younger women also work on the streets or in other venues. What factors push Thai women to enter the sex industry? A number of factors may push a woman in Thailand to enter the sex industry. ● Culture: In Thailand, a son’s duty is to “make merit” for his parents’ next life by serving time as a monk. By contrast, once a daughter is “of age,” she is culturally obligated to care for her parents. When a young woman’s marriage dissolves—usually due to adultery, alcohol, and domestic violence—there is no longer enough support by the husband for a woman to support her parents or her own children. As a result, when the opportunity to work in the city arises, she is often relieved to be able to meet her financial obligations through that work, no matter the sacrifice. -

Migrant Smuggling in Asia

Migrant Smuggling in Asia An Annotated Bibliography August 2012 2 Knowledge Product: !"#$%&'()!*##+"&#("&(%)"% An Annotated Bibliography Printed: Bangkok, August 2012 Authorship: United Nations O!ce on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) Copyright © 2012, UNODC e-ISBN: 978-974-680-330-4 "is publication may be reproduced in whole or in part and in any form for educational or non-pro#t purposes without special permission from the copyright holder, provided acknowledgement of the source is made. UNODC would appreciate receiving a copy of any publication that uses this publication as a source. No use of this publication may be made for resale or any other commercial purpose whatsoever without prior permission in writing from the United Nations O!ce on Drugs and Crime. Applications for such permission, with a statement of purpose and intent of the reproduction, should be addressed to UNODC, Regional Centre for East Asia and the Paci#c. Cover photo: Courtesy of OCRIEST Product Feedback: Comments on the report are welcome and can be sent to: Coordination and Analysis Unit (CAU) Regional Centre for East Asia and the Paci#c United Nations Building, 3 rd Floor Rajdamnern Nok Avenue Bangkok 10200, "ailand Fax: +66 2 281 2129 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.unodc.org/eastasiaandpaci#c/ UNODC gratefully acknowledges the #nancial contribution of the Government of Australia that enabled the research for and the production of this publication. Disclaimers: "is report has not been formally edited. "e contents of this publication do not necessarily re$ect the views or policies of UNODC and neither do they imply any endorsement. -

Emancipating Modern Slaves: the Challenges of Combating the Sex

Union College Union | Digital Works Honors Theses Student Work 6-2013 Emancipating Modern Slaves: The hC allenges of Combating the Sex Trade Rachel Mann Union College - Schenectady, NY Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalworks.union.edu/theses Part of the Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons, Inequality and Stratification Commons, and the Political Science Commons Recommended Citation Mann, Rachel, "Emancipating Modern Slaves: The hC allenges of Combating the Sex Trade" (2013). Honors Theses. 700. https://digitalworks.union.edu/theses/700 This Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Work at Union | Digital Works. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of Union | Digital Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. EMANCIPATING MODERN SLAVES: THE CHALLENGES OF COMBATING THE SEX TRADE By Rachel J. Mann * * * * * * * * * Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for Honors in the Department of Political Science UNION COLLEGE June, 2013 ABSTRACT MANN, RACHEL Emancipating Modern Slaves: The Challenges of Combating the Sex Trade, June 2013 ADVISOR: Thomas Lobe The trafficking and enslavement of women and children for sexual exploitation affects millions of victims in every region of the world. Sex trafficking operates as a business, where women are treated as commodities within a global market for sex. Traffickers profit from a supply of vulnerable women, international demand for sex slavery, and a viable means of transporting victims. Globalization and the expansion of free market capitalism have increased these factors, leading to a dramatic increase in sex trafficking. Globalization has also brought new dimensions to the fight against sex trafficking. -

Combating Trafficking of Women and Children in South Asia

CONTENTS COMBATING TRAFFICKING OF WOMEN AND CHILDREN IN SOUTH ASIA Regional Synthesis Paper for Bangladesh, India, and Nepal APRIL 2003 This book was prepared by staff and consultants of the Asian Development Bank. The analyses and assessments contained herein do not necessarily reflect the views of the Asian Development Bank, or its Board of Directors or the governments they represent. The Asian Development Bank does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this book and accepts no responsibility for any consequences of their use. i CONTENTS CONTENTS Page ABBREVIATIONS vii FOREWORD xi EXECUTIVE SUMMARY xiii 1 INTRODUCTION 1 2 UNDERSTANDING TRAFFICKING 7 2.1 Introduction 7 2.2 Defining Trafficking: The Debates 9 2.3 Nature and Extent of Trafficking of Women and Children in South Asia 18 2.4 Data Collection and Analysis 20 2.5 Conclusions 36 3 DYNAMICS OF TRAFFICKING OF WOMEN AND CHILDREN IN SOUTH ASIA 39 3.1 Introduction 39 3.2 Links between Trafficking and Migration 40 3.3 Supply 43 3.4 Migration 63 3.5 Demand 67 3.6 Impacts of Trafficking 70 4 LEGAL FRAMEWORKS 73 4.1 Conceptual and Legal Frameworks 73 4.2 Crosscutting Issues 74 4.3 International Commitments 77 4.4 Regional and Subregional Initiatives 81 4.5 Bangladesh 86 4.6 India 97 4.7 Nepal 108 iii COMBATING TRAFFICKING OF WOMEN AND CHILDREN 5APPROACHES TO ADDRESSING TRAFFICKING 119 5.1 Stakeholders 119 5.2 Key Government Stakeholders 120 5.3 NGO Stakeholders and Networks of NGOs 128 5.4 Other Stakeholders 129 5.5 Antitrafficking Programs 132 5.6 Overall Findings 168 5.7 -

Modernity for Young Rural Migrant Women Working in Garment Factories in Vientiane

MODERNITY FOR YOUNG RURAL MIGRANT WOMEN WORKING IN GARMENT FACTORIES IN VIENTIANE ຄວາມເປັນສະໄໝໃໝສ່ າ ລບັ ຍງິ ສາວທ່ ເປັນແຮງງານຄ່ ອ ນ ຍາ້ ຍ ເຮັດວຽກໃນໂຮງງານ-ຕດັ ຫຍບິ ຢນ່ ະຄອນຫຼວງ ວຽງຈນັ Ms Rakounna SISALEUMSAK MASTER DEGREE NATIONAL UNIVERISTY OF LAOS 2012 MODERNITY FOR YOUNG RURAL MIGRANT WOMEN WORKING IN GARMENT FACTORIES IN VIENTIANE ຄວາມເປັນສະໄໝໃໝສ່ າ ລບັ ຍງິ ສາວທ່ ເປັນແຮງງານເຄ່ ອ ນ ຍາ້ ຍເຮັດວຽກໃນໂຮງງານ-ຕດັ ຫຍບິ ຢນ່ ະຄອນຫຼວງວຽງຈນັ A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE OFFICE IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE MASTER DEGREE IN INTERNATIONAL DEVELOPMENT STUDIES Rakounna SISALEUMSAK National University of Laos Advisor: Dr. Kabmanivanh PHOUXAY Chiang Mai University Advisor: Assistant Professor Dr. Pinkaew LAUNGARAMSRI © Copyright by National University of Laos 2012 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This thesis would not have been accomplished without valuable help and inputs from numerous people. First of all I would like to express my sincere appreciation to my supervisors Dr. Kabmanivanh Phouxay and Assistant Professor Dr. Pinkaew Laungaramsri for their valuable support, critical comments and advice which has helped shaped my thesis. In addition I would also like to express my sincere gratitude to Dr. Chayan Vaddhanaphuti, for the constant guidance and advice provided which has helped to deepen my understanding of the various concepts and development issues. I also wish to thank all the lecturers, professors and staff, from NUOL and CMU, for helping to increase my knowledge and widen my perspectives on development issues in Laos and in the region. My special thanks to Dr Seksin Srivattananukulkit for advising me to take this course and also to Dr Chaiwat Roongruangsee for his constant encouragement and words of wisdom which has helped motivate me to continue to write this thesis. -

Combating Child Sex Tourism in a New Tourism Destination

DECLARATION Name of candidate: Phouthone Sisavath This thesis entitled: “Combating Child Sex Tourism in a new tourism destination” is submitted in partial fulfilment for the requirement for the Unitec New Zealand degree of Master of Business. CANDIDATE’S DECLARATION I confirm that: This thesis is my own work The contribution of supervision and others to this thesis is consistent with Unitec‟s Regulations and Policies Research for this thesis has been conducted with approval of the Unitec Research Ethics Committee Policy and Procedure, and has fulfilled any requirements set for this thesis by the Unitec Ethics Committee. The Research Ethics Committee Approval Number is: 2011-1211 Candidate Signature:..............................................Date:…….……….………… Student ID number: 1351903 i ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This thesis would not have been completed without the support and assistance of some enthusiastic people. I would like to thank the principal supervisor of the thesis, Prof. Ken Simpson. He has provided the most valuable and professional guidance and feedback, and he gave me the most support and encouragement in the research. I would also like to thank the associate supervisor, Ken Newlands for his valuable comments on the draft of the thesis. I would also like to give a big thank you to all active participants from both the Lao government agencies and international organisations, which have provided such meaningful information during the research. I would also like to acknowledge and give specially thank to my parents. I might not get to where I am today without their support and encouragement throughout my study here in New Zealand. Finally, I wish to thank my lovely partner Vilayvanh for her understanding and patience and for her consistent positive attitude in every condition and situation. -

Prostitution Stigma and Its Effect on the Working Conditions, Personal Lives, and Health of Sex Workers

The Journal of Sex Research ISSN: 0022-4499 (Print) 1559-8519 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/hjsr20 Prostitution Stigma and Its Effect on the Working Conditions, Personal Lives, and Health of Sex Workers Cecilia Benoit, S. Mikael Jansson, Michaela Smith & Jackson Flagg To cite this article: Cecilia Benoit, S. Mikael Jansson, Michaela Smith & Jackson Flagg (2017): Prostitution Stigma and Its Effect on the Working Conditions, Personal Lives, and Health of Sex Workers, The Journal of Sex Research, DOI: 10.1080/00224499.2017.1393652 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2017.1393652 Published online: 17 Nov 2017. Submit your article to this journal View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=hjsr20 Download by: [University of Victoria] Date: 17 November 2017, At: 13:09 THE JOURNAL OF SEX RESEARCH,00(00), 1–15, 2017 Copyright © The Society for the Scientific Study of Sexuality ISSN: 0022-4499 print/1559-8519 online DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2017.1393652 ANNUAL REVIEW OF SEX RESEARCH SPECIAL ISSUE Prostitution Stigma and Its Effect on the Working Conditions, Personal Lives, and Health of Sex Workers Cecilia Benoit and S. Mikael Jansson Centre for Addictions Research of British Columbia, University of Victoria; and Centre for Addictions Research of British Columbia, University of Victoria Michaela Smith Centre for Addictions Research of British Columbia, University of Victoria; Jackson Flagg Centre for Addictions Research of British Columbia, University of Victoria Researchers have shown that stigma is a fundamental determinant of behavior, well-being, and health for many marginalized groups, but sex workers are notably absent from their analyses. -

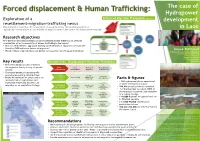

Exploration of a Resettlement-Migration–Trafficking

Forced displacement & Human Trafficking: The case of Hydropower Exploration of a Drivers of Migration Framework (Adaptation7) development resettlement-migration–trafficking nexus This research is located at the convergence of two phenomena; the rapid development of in Laos hydropower infrastructure in Laos and the country's location at the center of a human trafficking hub. Research objectives How Development-Induced-Displacement and Resettlement (DIDR) places affected communities at an increased risk of human trafficking in the region? • How can resettlement aggravate existing vulnerabilities of impacted communities? Village Focus International Francesco Brembati (The Lily) • How does DIDR influence drivers of migration? Anouk Malboeuf • Which of these vulnerabilities and drivers increases the risk of human trafficking? MA Refugee Protection & Forced Migration Contact: [email protected] University of London Refugee Law Initiative 4th annual conference Key results Possible links: Displacement-Migration-Trafficking 3-5 June 2019Li Fan • The resettlement process influences Li Fan the migration flux by acting on specific Prior Post Drivers of Determinants drivers; resettlement resettlement migration of trafficking • The resettlement process generally exacerbates existing vulnerabilities; Fragile Difficult Survival & New livelihood adaptation & • Resettled communities are placed at an food/water risky migration 1 insecurity Facts & figures increased risk of exploitation and security • ± 100 hydropower plants operational trafficking when they decide to use Capacity to Cash pay or under construction in Laos. Subsistence compensation New financial migration as an adaptation strategy. smugglers/ / cash based capacities • 280,000 peoples could be resettled. agriculture false sense of Asian News Network economy security • For the Nam Man 3 project, 100% of Improved road Attraction to the resettled household used migration 6 Increase Isolated rural access, contact modern life, marriage with with foreigners access to as a coping strategy. -

Child Prostitution in Thailand

Child prostitution in Thailand The state as a barrier to its effective elimination Candidate: Ornella Barros Submission deadline: 15/05/2014 Number of words: 19.896 Supervisor: Else Leona McClimans, Stener Ekern. Acknowledgments I would like to extend my gratitude to Else Leona McClimans for her guidance and support along the writing process of this thesis. Her expertise and interest in the topic was a great inspiration from the very beginning. I would also thank Stener Ekern for his invaluable and constructive feedback in the last phase of the document. The reality of such a sensitive issue could not have been described without the perspectives from the inside. For this reason, I am so grateful with the organizations ECPAT Interna- tional, ECPAT Foundation, Plan International Thailand Foundation, and Childline for their outstanding will to contribute and being part of the study. This experience would not have been as enriching without the inspiration and professional background provided by my work with Gestores de Paz. Their leadership and commitment towards the construction of a better world for children has its traces in this study. I do ap- preciate the opportunity I had to be part of such a valuable work. A heartfelt gratitude goes to my parents Matilde and Oscar for believing in me, and for being my best motivation. Special thanks to my sister Oriana for her unconditional support every time I needed it; and Nicolas, for being my family during these two years. To every single person that has been part of this awesome journey from beginning to end, my grati- tude and love. -

[email protected]

Letmather Str.71, 58119 Hagen, Germany. Phone: 0049( 2334) 44 44 668, E-Mail: [email protected] www.laoalliance.org SDG Report for Laos by the Alliance for Democracy in Laos 2021 1. End Poverty in All its Forms Everywhere If you follow the World Bank figures, Laos has achieved some success in combating poverty in recent years. However, these successes are in danger due to the COVID-19 pandemic and the still escalating corruption in Laos. Independent experts even report that poverty remains high and that the reports by the government of Laos are not true. The reports that we receive from our employees in Laos indicate this. An indication of the still great poverty in the country is the high youth unemployment. In the CIA Factbook this is estimated at 18.5%. https://www.cia.gov/the-world-factbook/countries/laos/ Typical Lao village in the Luang Phrabang province (2019) But other sources also confirm the reports of our employees. Laos still ranks 137th in the HDI index. The causes of poverty are not just corruption, but also the lack of infrastructure in Laos and the underdeveloped economy. Another sure sign of extreme poverty is the fact that there are very many school dropouts in Laos. Many children are forced to leave school early and earn money. 1 https://www.rfa.org/lao/daily/women-children/human-development-in-laos-short-of-target- 12302020015923.html The government of the Laotian People's Republic currently puts annual economic growth at 4.6%. However, since development aid projects are also included in the figures for economic output, one must assume that real growth is more likely to be around 0%. -

Sex Work and the Law in Asia and the Pacific — UNDP

SEX WORK AND THE LAW IN ASIA AND THE PACIFIC SEX WORK AND THE LAW IN ASIA AND THE PACIFIC THE AND ASIA IN LAW THE AND WORK SEX Empowered lives. Resilient nations. United Nations Development Programme UNDP Asia-Paci c Regional Centre United Nations Service Building, 3rd Floor Rajdamnern Nok Avenue, Bangkok 10200, Thailand Email: [email protected] Tel: +66 (0)2 304-9100 Fax: +66 (0)2 280-2700 Web: http://asia-paci c.undp.org/ October 2012 Empowered lives. Resilient nations. The information contained in this report is drawn from multiple sources including consultation responses, an extensive literature review and expert inputs. While every effort has been taken to ensure accuracy at the time of publication, errors or omissions may have occurred. Laws, policies and law enforcement practices are constantly changing. It is hoped that the report will provide a baseline of information, to inform more detailed efforts at country level to build an accurate and complete evidence base to inform efforts to address the health and human rights of sex workers. The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of the United Nations, including UNDP, or UN Member States. UNDP partners with people at all levels of society to help build nations that can withstand crisis, and drive and sustain the kind of growth that improves the quality of life for everyone. On the ground in 177 countries and territories, we offer global perspective and local insight to help empower lives and build resilient nations. Copyright © UNDP 2012 ISBN: 978-974-680-343-4 United Nations Development Programme UNDP Asia-Pacific Regional Centre United Nations Service Building, 3rd Floor Rajdamnern Nok Avenue, Bangkok 10200, Thailand Email: [email protected] Tel: +66 (0)2 304-9100 Fax: +66 (0)2 280-2700 Web: http://asia-pacific.undp.org/ Design: Ian Mungall/UNDP. -

Annual Report 2019

ANNUAL REPORT 2019 1 “As an innovati ve model of social inclusion, the Special Rapporteur has been impressed by the work carried out by the Free a Girl NGO, in the context of the School for Justi ce project implemented in India and Nepal.” - Report to the UN Human Rights Council by the Special Rapporteur on traffi cking in persons, Dr. Maria Grazia Giammarinaro Free a Girl Foundati on Hendrik Figeeweg 3 G-10 2031 BJ HAARLEM +31 (0)23 2049400 freeagirl.com [email protected] Chamber of Commerce Amsterdam: 34308169 Rabobank: NL 40 RABO 0306898799 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. VISION, MISSION AND CORE VALUES 5 1.1 Vision 5 1.2 Mission 5 1.3 Core values 5 1.4 Objectives 5 1.4.1 Stop the sexual exploitation of children 6 1.4.2 Confront the public with the existence of child sexual exploitation 6 2. STOPPING SEXUAL EXPLOITATION 7 2.1 Bangladesh 7 2.2 Brazil 12 2.3 India 14 2.4 Nepal 20 2.5 Thailand 25 2.6 Laos 27 3. RAISING AWARENESS 32 3.1 Target group 32 3.2 Alliances 32 3.2.1 Down to Zero 32 3.2.2 Don’t look away 32 3.3 Online communication and free publicity 32 3.3.1 Ambassadors 32 3.3.2 Media value 2019 33 3.3.3 Website 33 3.3.4 Social media 33 3.4 Communication with stakeholders 33 3.4.1 Donors 34 3.4.2 Business partners 34 3.4.3 Foundations and private charitable foudations 34 3.4.4 Alliance partners 34 3.4.5 Ambassadors 34 3.4.6 Regional ambassadors 34 3.4.7 Employees 34 3.4.8 Partner organizations 34 3.4.9 Integrity and complaints procedure 35 3.5 Highlights 35 3.5.1 Fight as if she was your own 35 3.5.2 Fighting child prostitution in Laos and Thailand 36 4.