Collectively Voting One's Culture Laura L.L. Blevins Thesis Submitted

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

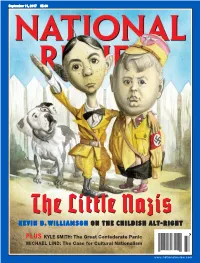

The Little Nazis KE V I N D

20170828 subscribers_cover61404-postal.qxd 8/22/2017 3:17 PM Page 1 September 11, 2017 $5.99 TheThe Little Nazis KE V I N D . W I L L I A M S O N O N T H E C HI L D I S H A L T- R I G H T $5.99 37 PLUS KYLE SMITH: The Great Confederate Panic MICHAEL LIND: The Case for Cultural Nationalism 0 73361 08155 1 www.nationalreview.com base_new_milliken-mar 22.qxd 1/3/2017 5:38 PM Page 1 !!!!!!!! ! !! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !! "e Reagan Ranch Center ! 217 State Street National Headquarters ! 11480 Commerce Park Drive, Santa Barbara, California 93101 ! 888-USA-1776 Sixth Floor ! Reston, Virginia 20191 ! 800-USA-1776 TOC-FINAL_QXP-1127940144.qxp 8/23/2017 2:41 PM Page 1 Contents SEPTEMBER 11, 2017 | VOLUME LXIX, NO. 17 | www.nationalreview.com ON THE COVER Page 22 Lucy Caldwell on Jeff Flake The ‘N’ Word p. 15 Everybody is ten feet tall on the BOOKS, ARTS Internet, and that is why the & MANNERS Internet is where the alt-right really lives, one big online 35 THE DEATH OF FREUD E. Fuller Torrey reviews Freud: group-therapy session The Making of an Illusion, masquerading as a political by Frederick Crews. movement. Kevin D. Williamson 37 ILLUMINATIONS Michael Brendan Dougherty reviews Why Buddhism Is True: The COVER: ROMAN GENN Science and Philosophy of Meditation and Enlightenment, ARTICLES by Robert Wright. DIVIDED THEY STAND (OR FALL) by Ramesh Ponnuru 38 UNJUST PROSECUTION 12 David Bahnsen reviews The Anti-Trump Republicans are not facing their challenges. -

October 20, 2017

Distributed Free Each Friday Since 2009 October 20, 2017 www.pcpatriot.com Locally Owned And Operated ELECTION PREVIEW INSIDE Candidates sharply differ on gun issues RICHMOND, Va. (AP) — The two major party to be able to carry a concealed candidates in Virginia's race for governor sharply handgun without a permit. disagree when it comes to guns. Earlier this year, Democratic Republican Ed Gillespie has an A rating from the Gov. Terry McAuliffe vetoed National Rifle Association. He pledged to "oppose legislation allowing that — any and all attempts to weaken the Second against the wishes of the GOP- Amendment." controlled General assembly. Democrat Ralph Northam said he favors stricter Democrats in the legislature controls on gun ownership. He's backed by former have pushed unsuccessfully for New York City Mayor Michael Bloomberg's group Gillespie universal background checks, as well as by former Democratic Rep. Gabrielle including mandatory checks at Giffords, who was grievously wounded in a 2011 gun shows. shooting. Governors also can take uni- The positions play against type. Northam grew lateral action on guns, like up hunting on Virginia's Eastern Shore and owns McAuliffe did in banning guns two shotguns. from certain state-owned office Gillespie wrote in his 2006 book that he doesn't buildings by executive order. own a gun and recently declined to answer whether Guns on campuses are also a that was still the case. regular and poignant point of discussion due to the 2007 THE ISSUE: mass shooting at Virginia Tech. Northam Debates about guns take up a significant amount Liberty University President WEEKEND WEATHER of time each legislative session and groups on both Jerry Falwell Jr. -

Most Local 400-Recommended Candidates Win

Keeping Up the Fight here are no guarantees in life. friend who helped enact Big Box legisla- class: Bills making it harder for workers You can work tirelessly, fight tion when he chaired the Fairfax County to gain union representation and stacking tenaciously, battle fiercely and Board of Supervisors, narrowly won re- the deck even more in favor of manage- T still lose. We saw that national- election in a district designed to be a safe ment. Draconian cuts in unemployment ly on Tuesday, November 2nd. Republican seat. And in the primaries, we compensation, veterans’ benefits, student Actually, there is one won a host of hotly com- aid, food and nutrition programs, and a guarantee—if you sit on petitive races, including host of other services working families the sidelines, you’ll lose. We face those of Washington, D.C. need. Measures that reward corporations Because your adver- Mayor-elect Vincent Gray for taking jobs overseas and driving down saries will have the field an assault and Prince George’s wages and cutting benefits here at home. to themselves. Especially County Executive-elect Not to mention efforts to repeal or under- now that the Supreme on working Rushern Baker. We even mine the health security provided by the Court’s Citizens United helped oust four incum- Affordable Care Act. ruling allows corpora- families. bent Maryland state sena- So we must fight back. Hard. Even tions to spend unlimited tors who had voted though most of these efforts will be amounts of money to elect candidates against working families, replacing them stopped by a gridlocked Senate or who serve at their beck and call. -

Vienna/Oakton Connection ❖ November 14-20, 2018 Connection Editor Kemal Kurspahic News 703-778-9414 Or [email protected]

These Oakton Girl Scout conservation- ists are doing their part to create mon- arch habitats in the area. Girl Scouts Save Monarchs News, Page 5 Classifieds, Page 10 Classifieds, v Entertainment, Page 8 v Wexton Helps Dems Opinion, Page 4 HomeLifeStyle Take the House Page 7 News, Page 3 11-15-18 home in Requested Time sensitive material. material. sensitive Time Attention Postmaster: Postmaster: Attention ECR WSS ECR ‘Real Work of Advocacy Customer Postal permit #322 permit Easton, MD Easton, PAID Begins Again’ Postage U.S. News, Page 8 STD PRSRT Photo contributed Photo November 14-20, 2018 online at www.connectionnewspapers.com 2 ❖ Vienna/Oakton Connection ❖ November 14-20, 2018 www.ConnectionNewspapers.com Connection Editor Kemal Kurspahic News 703-778-9414 or [email protected] Photo by Marcus Sim Photo Photo by Michael Lee Pope Photo on via Facebook Former Gov. Terry McAuliffe tells the crowd assembled at Tim Kaine’s Packed house to celebrate Jennifer Wexton’s win in the 10th Congres- victory party that voters in Virginia rejected President Donald Trump’s sional District. campaign of “fear, hatred and division.” Democrats Seize Control of Northern Virginia Region once had its own brand of Republicanism; now that seems almost extinct. By Michael Lee Pope supporters taking a posi- The Connection and volun- Results tion as chair- Photo by Ken Pl Photo teers that U.S. SENATE man of a sub- ❖ he loss of two-term incumbent helped her Democrat Tim Kaine: ................. 1.9 million votes, 57 percent committee on ❖ Republican Corey Stewart: ........ 1.4 million votes, 41 percent U.S. -

June 19, 2020 Volume 4, No

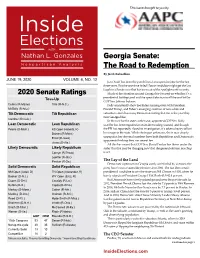

This issue brought to you by Georgia Senate: The Road to Redemption By Jacob Rubashkin JUNE 19, 2020 VOLUME 4, NO. 12 Jon Ossoff has been the punchline of an expensive joke for the last three years. But the one-time failed House candidate might get the last laugh in a Senate race that has been out of the spotlight until recently. 2020 Senate Ratings Much of the attention around Georgia has focused on whether it’s a Toss-Up presidential battleground and the special election to fill the seat left by GOP Sen. Johnny Isakson. Collins (R-Maine) Tillis (R-N.C.) Polls consistently show Joe Biden running even with President McSally (R-Ariz.) Donald Trump, and Biden’s emerging coalition of non-white and Tilt Democratic Tilt Republican suburban voters has many Democrats feeling that this is the year they turn Georgia blue. Gardner (R-Colo.) In the race for the state’s other seat, appointed-GOP Sen. Kelly Lean Democratic Lean Republican Loeffler has been engulfed in an insider trading scandal, and though Peters (D-Mich.) KS Open (Roberts, R) the FBI has reportedly closed its investigation, it’s taken a heavy toll on Daines (R-Mont.) her image in the state. While she began unknown, she is now deeply Ernst (R-Iowa) unpopular; her abysmal numbers have both Republican and Democratic opponents thinking they can unseat her. Jones (D-Ala.) All this has meant that GOP Sen. David Perdue has flown under the Likely Democratic Likely Republican radar. But that may be changing now that the general election matchup Cornyn (R-Texas) is set. -

Latest Poll Shows Gubernatorial Race Is Now a Dead Heat: 44-44 Here Are

Vol. 42, No 8 www.arlingtondemocrats.org August 2017 Latest poll shows gubernatorial The GOP may sue this conservative Virginia candidate race is now a dead heat: 44-44 over the The latest statewide poll shows a dead heat in 46 percent had no opinion. Gillespie was rated fa- the gubernatorial election with each major party vorably by 36 percent and unfavorably by 20 per- design of candidate drawing 44 percent support. cent with 44 percent having no opinion. his yard The poll, taken by Monmouth University in The poll found substantial regional differences. signs. New Jersey, surveyed 502 Virginians from July 20 Northam led in northern Virginia by 13 percentage to 23. points and in the eastern areas by 9 percentage points. The poll found only 3 percent support for Lib- Gillespie led by 2 percentage points in the center, a See Page ertarian Cliff Hyra and 1 percent for write-in candi- statistically meaningless difference, but by a whop- 5. dates, with 9 percent still undecided. That 9 per- ping 18 percentage points in the western areas. cent is enough to swing the election either way and The only other statewide poll published so far points to the need for a savvy campaign. was taken just after the primary by Quinnipiac Uni- As for issues, 37 percent put health care and versity and showed Northam with a comfortable health insurance as one of their top issues, which lead 47-39. would seem to play into the hands of Northam, a The race is expected to be an intense one with This Confederate-loving physician by profession. -

Roanoke College Poll Topline U.S. Senate Election August 22, 2018 Hi, I'm___And I'm Calling from Roanoke College. Ho

Roanoke College Poll Topline U.S. Senate Election August 22, 2018 Hi, I'm____________ and I'm calling from Roanoke College. How are you today/this evening? We're conducting a survey of Virginia residents regarding important issues and your opinion is very important to us. Your responses are confidential. 1. Are you registered to vote in Virginia? Yes 100% No [TERMINATE] 0% 2. How likely is it that you will vote in the election for senator in November? Is it very likely, somewhat likely, not very likely, or not likely at all? Very likely 86% Somewhat likely 14% Not very likely [TERMINATE] 0% Not likely at all [TERMINATE] 0% 3. Do you think things in the COUNTRY are generally going in the right direction or do you think things have gotten off on the wrong track? Right direction 37% Wrong track 56% Unsure 7% Refused 1% 4. Do you think things in the Commonwealth of Virginia re generally going in the right direction or do you think things have gotten off on the wrong track? Right direction 58% Wrong track 30% Unsure 10% Refused 2% 5. In general, do you approve or disapprove of the way Donald Trump is handling his job as President of the United States? Approve 32% Disapprove 53% Mixed 12% Don't Know/Refused 3% 6. In general, do you approve or disapprove of the way Ralph Northam is handling his job as Governor of Virginia? Approve 54% Disapprove 18% Mixed 13% Don't Know/Refused 15% 7. The 2018 election for senator is a few months away, but if the election for senator were held today, who would you vote for if the candidates were: [ROTATE FIRST THREE; READ FIRST THREE ONLY] Tim Kaine, the Democrat 49% Corey Stewart, the Republican 33% Matt Waters, the Libertarian 4% Undecided [VOLUNTERED ONLY] 14% 7. -

Virginia Survey Fall 2017

VIRGINIA SURVEY FALL 2017 PRINCETON SURVEY RESEARCH ASSOCIATES INTERNATIONAL FOR UNIVERSITY OF MARY WASHINGTON THIRD TOPLINE SEPTEMBER 20, 2017 NOTE: SOME QUESTIONS HAVE BEEN HELD FOR FUTURE RELEASE Total Interviews: 1,000 Virginia adults, age 18 or older 350 landline interviews 650 cell phone interviews Margins of error: ±3.8 percentage points for results based on Total [N=1,000] ±4.1 percentage points for results based on Registered voters [N=867] ±5.2 percentage points for results based on Likely voters [N=562] Interviewing dates: September 5-12, 2017 Interviewing language: English only Notes: Because percentages are rounded, they may not total 100%. An asterisk (*) indicates less than 0.5%. SURVEY INFORMATION The University of Mary Washington’s Virginia Survey Fall 2017 obtained telephone interviews with a representative sample of 1,000 adults, ages 18 or older, living in Virginia. Telephone interviews were conducted by landline (350) and cell phone (650, including 352 without a landline phone). The survey was conducted by Princeton Survey Research Associates International (PSRAI). Interviews were done in English under the direction of Princeton Data Source from September 5 to 12, 2017. Statistical results are weighted to correct known demographic discrepancies. The margin of sampling error for the complete set of weighted data is ± 3.8 percentage points. TREND INFORMATION September 2016 trends are from the University of Mary Washington’s Virginia Survey Fall 2016, conducted September 6-12, 2016 among 1,006 Virginia adults age 18+, including 852 registered voters, reached on either a landline or cell phone. November 2015 trends are from the University of Mary Washington’s Virginia Survey Fall 2015, conducted November 4-9, 2015 among 1,006 Virginia adults age 18+, including 814 registered voters, reached on either a landline or cell phone. -

A Case Study of the Southwest Virginia Higher Education Center. Susan Carey Fulmer East Tennessee State University

East Tennessee State University Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University Electronic Theses and Dissertations Student Works 5-2002 The evelopmeD nt of a Higher Education Consortium: A Case Study of the Southwest Virginia Higher Education Center. Susan Carey Fulmer East Tennessee State University Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.etsu.edu/etd Part of the Higher Education Administration Commons Recommended Citation Fulmer, Susan Carey, "The eD velopment of a Higher Education Consortium: A Case Study of the Southwest Virginia Higher Education Center." (2002). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 674. https://dc.etsu.edu/etd/674 This Dissertation - Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Works at Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Development of a Higher Education Consortium: A Case Study of The Southwest Virginia Higher Education Center A dissertation presented to the faculty of the Department of Educational Leadership and Policy Analysis East Tennessee State University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor in Education by Susan Carey Fulmer May 2002 Dr. Russell West, Chair Dr. Nancy Dishner Dr. Terrence Tollefson Dr. Ronald Green Keywords: Consortium, Higher Education, Case Study, Extended Campuses, Off-Campus Instruction, Distance Education, Adult Learners ABSTRACT The Development of a Higher Education Consortium: A Case Study of The Southwest Virginia Higher Education Center by Susan Carey Fulmer The purpose of this study was to describe the creation and development of the Southwest Virginia Higher Education Center (SVHEC) in Abingdon, Virginia as an example of a higher education consortium. -

The Proud Boys: a Republican Party Street Gang in Search of New Frames: Q&A with the Authors of Producers, Parasites, Patriots Editor’S Letter

SPRING 2019 The Public Eye In this issue: The Intersectional Right: A Roundtable on Gender and White Supremacy Aberration or Reflection? How to Understand Changes on the Political Right The Proud Boys: A Republican Party Street Gang In Search of New Frames: Q&A with the Authors of Producers, Parasites, Patriots editor’s letter THE PUBLIC EYE QUARTERLY Last November, PRA worked with writer, professor, and longtime advocate Loretta PUBLISHER Ross to convene a conversation about the relationship between gender and White su- Tarso Luís Ramos premacy. For decades, Ross says, too many fight-the-Right organizations neglected EDITOR Kathryn Joyce to pay attention to this perverse, right-wing version of intersectionality, although its COVER ART impacts were numerous—evident in overlaps between White supremacist and anti- Danbee Kim abortion violence; in family planning campaigns centered on myths of overpopula- PRINTING tion; in concepts of White womanhood used to further repression and bigotry; and in Red Sun Press how White women themselves formed the backbone of segregationist movements. By contrast, today there is a solid core of researchers and activists working on this issue. At November’s meeting, PRA spoke to a number of them (pg. 3) about their work, the The Public Eye is published by current stakes, and the way forward. Political Research Associates Tarso Luís Ramos Our second feature this issue, by Carolyn Gallaher, looks at another dynamic situ- EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR ation: how to understand changes on the political Right (pg. 9). Since Trump came Frederick Clarkson to power, numerous conservative commentators—mostly “never Trumpers”—have SENIOR ReseARCH ANALYST predicted (or declared) the death of the Republican Party. -

Sensitiv®*^Ei^Al Election Commission 5=3"

RECEIVED FEDERAL ELECTION COMMISSION 1 SENSITIV®*^EI^AL ELECTION COMMISSION 2 999 E Street, N.W. 2013 JAN 17 PH 12: 19 3 Washington, D.C. 20463 4 5 FIRST GENERAL COUNSEL'S REPORT CELA 6 7 MUR: 6589 8 DATE OF COMPLAINT: 6/7/12 9 DATE OF NOTIFICATION: 6/12/12 10 DATE OF LAST RESPONSE: 10/1/12 11 DATE ACTIVATED: 8/20/12 12 J 13 EXPIRATION OF SOL: 7/23/14 14 15 COMPLAINANTS: Citizens for Responsibility and Ethics in 16 Washington 17 18 Melanie Sloan 19 20 RESPONDENT: American Action Network and Stephanie Fenjiro in 21 her capacity as treasurer 22 23 RELEVANT STATUTES 24 AND REGULATIONS: 2U.S.C.§431(4) 25 2 U.S.C. § 432 r~0 26 2 U.S.C. § 433 C9 27 434 O* 2 U.S.C. § c_ P! 28 s»» 26 U.S.C. § 501(c) IS: 29 11C.F.R.§ 100.22 30 31 INTERNAL REPORTS CHECKED: Disclosure Reports -o 32 — 5=3" PO« • •• o 33 FEDERAL AGENCIES CHECKED: None ro ro MUR 6589 (American Action Network) General Counsel's Report Page 2 of27 TABLE OF CONTENTS 2 I. INTRODUCTION 3 3 II. FACTUAL AND LEGAL ANALYSIS 3 4 A. Facts 3 5 1. AAN 3 6 2. AAN's Activities 4 7 B. Analysis 5 8 1. The Test for Political Committee Status 5 4 9 a. The Commission's Case-By-Case Approach to Major Purpose 5 10 b. Challenges to the Commission's Major Purpose Test and the 11 Supplemental E&J 7 12 c. -

Virginia Capitol Connections Virginia Capitol

Virginia Capitol Connections Summer 2010 Elect No Strangers Virginia’s Directory of Candidates for Public Office 2010 Summer Red & Blue Book Email [email protected] with any edits for our online version on our web, dbava.com. Eateries David Napier’s White House Catering Historic Shockoe Bottom • 804-644-4411 Grandpa Eddie’s Alabama Ribs & BBQ 11129 Three Chopt Road • 804-270-RIBS Meriwether’s at the Assembly 804-698-7438 • The Capitol • 804-698-7692, GAB Hotels Doubletree Hotel Richmond Downtown 301 West Franklin Street, Richmond • 804-644-9871 Hampton-Inn Richmond Airport 421 International Center Drive, Sandston • 804-226-1888 Holiday-Inn Richmond Airport 445 International Center Drive, Sandston • 804-236-1111 Holiday-Inn Express Richmond Downtown 201 East Cary Street, Richmond • 804-788-1600 Homewood Suites Richmond Airport 5996 Audubon Drive, Sandston • 804-737-1600 OMNI Richmond Hotel 100 South 12th Street, Richmond • 804-344-7000 Richmond Marriott-Downtown (newly renovated) 500 East Broad Street, Richmond • 804-643-3400 The Berkeley Hotel (Per diem rates offered, restrictions apply) 1200 East Cary Street, Richmond • 804-780-1300 Westin Richmond 6631 West Broad Street, Richmond • 804-282-8444 Parking Parkway Parking of Virginia Daily or monthly available 706 E. Leigh Street–enter from 8th, 7th or Jackson Paul Daley, City Manager, 804-339-3233 [email protected] Services Connie’s Shoe Repair 110 N. 8th Street • 804-648-8896 Virginia Capitol Connections, 3rd Edition 2010 Volume 24—Copyright ©2010 David L. Bailey A nonpartisan