A Brief History of the Sacrament of Reconciliation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Centrality of the Holy Sacrifice of the Mass at Christendom College

THE CENTRALITY OF THE HOLY SACRIFICE OF THE MASS AT CHRISTENDOM COLLEGE The Church teaches that the Eucharist is “the source and summit of the Christian life”1 and that the celebration of the Mass “is a sacred action surpassing all others. No other action of the Church can equal its efficacy.”2 That is why “as a natural expression of the Catholic identity of the University. members of this community . will be encouraged to participate in the celebration of the sacraments, especially the Eucharist, as the most perfect act of community worship.”3 Those central truths are taught and lived at Christendom College, a “Catholic coeducational college institutionally committed to the Magisterium”4 of the Church, in the following ways: The Celebration of the Sacred Liturgy The Holy Sacrifice of the Mass • Mass is offered frequently: twice daily Monday through Thursday, three times on MONDAY (Friday), twice on Saturday, and once on Sunday (the day on which we gather as one family). • Mass in the Roman Rite is celebrated in all the ways offered by the Church: in the Ordinary Form in both English and Latin, and in the Extraordinary Form from one to three times per week, as circumstances permit. • The Ordinary Form of the Mass is celebrated with the solemnity appropriate to each feast, utilizing worthy sacred vessels and vestments, and drawing upon the Church’s rich tradition of chant, polyphony, and hymnody. • The Ordinary Form of the Mass is celebrated reverently and with rubrical fidelity. • No classes or other activities are scheduled during Mass times. • The majority of the College community attends daily Mass regularly and with great devotion. -

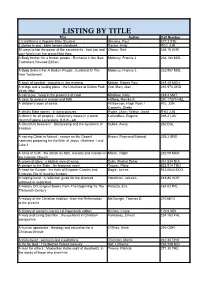

Parish Library Listing

LISTING BY TITLE Title Author Call Number 2 Corinthians (Lifeguide Bible Studies) Stevens, Paul 227.3 STE 3 stories in one : bible heroes storybook Rector, Andy REC JUN 50 ways to tap the power of the sacraments : how you and Ghezzi, Bert 234.16 GHE your family can live grace-filled lives A Body broken for a broken people : Eucharist in the New Moloney, Francis J. 234.163 MOL Testament Revised Edition A Body Broken For A Broken People : Eucharist In The Moloney, Francis J. 232.957 MOL New Testament A book of comfort : thoughts in late evening Mohan, Robert Paul 248.48 MOH A bridge and a resting place : the Ursulines at Dutton Park Ord, Mary Joan 255.974 ORD 1919-1980 A call to joy : living in the presence of God Matthew, Kelly 248.4 MAT A case for peace in reason and faith Hellwig, Monika K. 291.17873 HEL A children's book of saints Williamson, Hugh Ross / WIL JUN Connelly, Sheila A child's Bible stories : in living pictures Ryder, Lilian / Walsh, David RYD JUN A church for all peoples : missionary issues in a world LaVerdiere, Eugene 266.2 LAV church Eugene LaVerdiere, S.S.S - edi A Church to believe in : Discipleship and the dynamics of Dulles, Avery 262 DUL freedom A coming Christ in Advent : essays on the Gospel Brown, Raymond Edward 226.2 BRO narritives preparing for the Birth of Jesus : Matthew 1 and Luke 1 A crisis of truth - the attack on faith, morality and mission in Martin, Ralph 282.09 MAR the Catholic Church A crown of glory : a biblical view of aging Dulin, Rachel Zohar 261.834 DUL A danger to the State : An historical novel Trower, Philip 823.914 TRO A heart for Europe : the lives of Emporer Charles and Bogle, James 943.6044 BOG Empress Zita of Austria-Hungary A helping hand : A reflection guide for the divorced, Horstman, James L. -

The Virtue of Penance in the United States, 1955-1975

THE VIRTUE OF PENANCE IN THE UNITED STATES, 1955-1975 Dissertation Submitted to The College of Arts and Sciences of the UNIVERSITY OF DAYTON In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for The Degree Doctor of Philosophy in Theology By Maria Christina Morrow UNIVERSITY OF DAYTON Dayton, Ohio December 2013 THE VIRTUE OF PENANCE IN THE UNITED STATES, 1955-1975 Name: Morrow, Maria Christina APPROVED BY: _______________________________________ Sandra A. Yocum, Ph.D. Committee Chair _______________________________________ William L. Portier, Ph.D. Committee Member Mary Ann Spearin Chair in Catholic Theology _______________________________________ Kelly S. Johnson, Ph.D. Committee Member _______________________________________ Jana M. Bennett, Ph.D. Committee Member _______________________________________ William C. Mattison, III, Ph.D. Committee Member iii ABSTRACT THE VIRTUE OF PENANCE IN THE UNITED STATES, 1955-1975 Name: Morrow, Maria Christina University of Dayton Advisor: Dr. Sandra A. Yocum This dissertation examines the conception of sin and the practice of penance among Catholics in the United States from 1955 to 1975. It begins with a brief historical account of sin and penance in Christian history, indicating the long tradition of performing penitential acts in response to the identification of one’s self as a sinner. The dissertation then considers the Thomistic account of sin and the response of penance, which is understood both as a sacrament (which destroys the sin) and as a virtue (the acts of which constitute the matter of the sacrament but also extend to include non-sacramental acts). This serves to provide a framework for understanding the way Catholics in the United States identified sin and sought to amend for it by use of the sacrament of penance as well as non-sacramental penitential acts of the virtue of penance. -

Repentance, Penance, & the Forgiveness of Sins

REPENTANCE, PENANCE, & THE FORGIVENESS OF SINS Catholic translations of the Bible have often used the words “repentance” and “penance” interchangeably. Compare the Douay- Rheims Version with the New American Catholic Bible at Acts 2:38 and Acts 26:20 and you will see that these words (repentance & penance) are synonymous, words carrying the same meaning as the another. The Catholic Dictionary published by “Our Sunday Visitor”, a Catholic publication defines these words in the following ways: Repentance = Contrition for sins and the resulting embrace of Christ in conformity to Him. Penance or Penitence = Spiritual change that enables a sinner to turn away from sin. The virtue that enables human beings to acknowledge their sins with true contrition and a firm purpose of amendment. If there is any difference of meaning, I would suggest from pondering Greek definitions, that repentance (from the New Testament) 1 focuses on a change of heart, a change of mind and penance centers on the works of faith that this change of heart has produced. But both the change of heart and the works of faith go together; they are part of the same package. The Church has always taught that Christ’s death and resurrection brought reconciliation between God and humanity and that “the Lord entrusted the ministry of reconciliation to the Church.”1 The catechism teaches that because sin often wrongs the neighbor, while absolution forgives sin, “it does not remedy all the disorders sin has caused,”2 therefore the sinner must still recover his full spiritual health by doing works meet for repentance, that is, prove your repentance by what you do. -

(313 Duke Street) the BASILICA SCHOOL

July 4, 2021 The Fourteenth Sunday in Ordinary Time Very Rev. Edward C. Hathaway, Rector Rev. David A. Dufresne, Parochial Vicar Rev. Joseph B. Townsend, Parochial Vicar Rev. Noah C. Morey, In Residence Mr. Jordan Evans, Seminarian 310 South Royal Street + Alexandria, VA 22314 + 703.836.4100 + www.stmaryoldtown.org + [email protected] HOLY SACRIFICE OF THE MASS All Masses are live streamed at www.stmaryoldtown.org SUNDAY 7 a.m., 8:30 a.m., 10 a.m., 11:30 a.m., 1 p.m. and 5 p.m. MONDAY through FRIDAY 6:30 a.m., 8 a.m. and 12:10 p.m. SATURDAY 8:30 a.m. and 5 p.m. (Vigil for Sunday) TRADITIONAL LATIN MASS 7:30 p.m., Third Friday of the month FEDERAL HOLIDAYS and HOLY DAYS Check the website and bulletin SACRAMENT OF PENANCE MONDAY through FRIDAY After 12:10 p.m. Mass WEDNESDAY 7:30 to 8:30 p.m. SATURDAY 9 to 10 a.m. and 4 to 5 p.m. Rosary Monday through Friday before 8 a.m. Mass BASILICA HOURS and on Saturday before 8:30 a.m. Mass MONDAY through FRIDAY 5:30 a.m. to 9 p.m. Miraculous Medal Novena Monday 12 noon SATURDAY 7:30 a.m. to 6:30 p.m. Adoration of the Blessed Sacrament Wednesday 12:45 to 8:30 p.m. SUNDAY 6 a.m. to 6:30 p.m. Adoration with Holy Hour & Benediction Wednesday 7:30 to 8:30 p.m. OFFICE HOURS (313 Duke Street) First Friday Nocturnal Adoration MONDAY through FRIDAY 9 a.m. -

January 12, 2020

The Baptism of our Lord — January 12, 2020 SAINT MARY’S & SAINT ELIZABETH’S CATHOLIC CHURCHES Phone: 701-579-4312 FATHER GARY BENZ-PASTOR [email protected]; Cell Phone 701-509-9504; Rectory 701-579-4874 VICTOR DVORAK –DEACON www.stmaryschurchnewengland.com “After Jesus was baptized, He came up from the water . .” There is an old story of a German cob- bler who used to sit in the doorway of his cottage and work at his trade. He was always singing or humming as he worked and most of his tunes were of a religious nature. One day, a Jewish merchant passed by and he was attracted by the cheerful appearance and the cheery song of the worker. “My friend,” remarked the Jew, “You seem exceedingly happy.” “I am,” remarked the cobbler, “I have good reason for it, since I am a King’s son.” The Jew continued on his way, thinking to himself that this guy was a mental case. Imagine, a peasant calling himself the son of a king! A few days later, the Jew passed the same cottage. “Good morning your royal highness,” was the Jew’s half scornful greeting. “Good morning,” said the cobbler. He continued, “I wonder if you believe that I am not the son of a king. Let me explain what I mean. As a Christian, I was baptized and Baptism makes one an adopted child of the King of heaven.” The Jew was so impressed that as he contemplated this in the following days and weeks, he eventually decided to seek Baptism and enter the Church. -

Rite of Penance Introduction

RITE OF PENANCE INTRODUCTION I The Mystery of Reconciliation in the History of Salvation 2 II The Reconciliation of Penitents in the Church’s Life 2 The Church is Holy but always in need of Purification 2 Penance in the Church’s Life and Liturgy 2 Reconciliation with God and with the Church 3 The Sacrament of Penance and Its Parts 3 a) Contrition 3 b) Confession 3 c) Act of Penance (Satisfaction) 3 d) Absolution 3 The Necessity and Benefit of the Sacrament 4 II Offices and Ministries in the Reconciliation of Penitents 4 The Community in the Celebration of Penance 4 The Minister of the Sacrament of Penance 4 The Pastoral Exercise of This Ministry 4 The Penitent 5 IV The Celebration of the Sacrament of Penance 5 The Place of Celebration 5 The Time of Celebration 5 Liturgical Vestments 5 A Rite for the Reconciliation of Individual Penitents 5 Preparation of Priest and Penitent 5 Welcoming the Penitent 5 Reading the Word of God 6 Confession of Sins and the Act of Penance 6 The Prayer of the Penitent and the Absolution by the Priest 6 Proclamation of Praise and Dismissal of the Penitent 6 Short Rite 6 B Rite for Reconciliation of Several Penitents with Individual Confession and Absolution 6 Introductory Rites 7 The Celebration of the Word of God 7 The Rite of Reconciliation 7 Dismissal of the People 8 C Rite for Reconciliation of Penitents with General Confession and Absolution 8 The Discipline of General Absolution 8 The Rite of General Absolution 8 V Penitential Celebrations 9 Nature and Structure 9 Benefit and Importance 9 VI Adaptations -

National Catholic Educational Association

SEMINARY JOURNAL VOlUme eighteeN NUmber ONe SPriNg 2012 Theme: Evangelization From the Desk of the Executive Director Msgr. Jeremiah McCarthy The New Evangelization and the Formation of Priests for Today Most Rev. Edward W. Clark, S.T.D. A Worldly Priest: Evangelization and the Diocesan Priesthood Rev. Matthew Ramsay For I Was a Stranger and You Welcomed Me Cardinal Roger Mahony Teaching Catechesis to Seminarians: A Fusion of Knowledge and Pedagogy Jim Rigg, Ph.D. International Priests in the United States: An Update Rev. Aniedi Okure, O.P. Emphasizing Relationality in Distance Learning: Looking toward Human and Spiritual Formation Online Dr. Sebastian Mahfood, O.P., and Sr. Paule Pierre Barbeau, O.S.B., Ph.D. Pastoral Ministry: Receiving Even While Giving Deacon James Keating, Ph.D. On a Dominican Vision of Theological Education Ann M. Garrido, D.Min. Priest as Catechetical Leader Diana Dudoit Raiche, Ph.D. Mountain Men: Preparing Seminarians for the Spiritual Trek Sr. Mary Carroll, S.S.S.F. Virtual Reality Requiring Real Virtue Msgr. Anthony J. Ireland, S.T.D. The Heart of the Matter Most Rev. Edward Rice Catholic Ministry Formation Enrollment: Statistical Overview for 2011-2012 Mary Gautier, Ph.D. BOOK REVIEW Life and Lessons from a Warzone: A Memoir of Dr. Robert Nyeko Obol by Robert Obol Reviewed by Dr. Sebastian Mahfood, O.P., Ph.D. National Catholic Educational Association The logo depicts a sower of seed and reminds us of the derivation of the word “seminary” from the Latin word “seminarium,” meaning “a seed plot” or “a place where seedlings are nurtured and grow.” SEMINARY JOURNAL VOLUME 18 NUMBER ONE SPRING 2012 Note: Due to leadership changes in the Seminary Department, this volume was actually published in April 2013. -

Sacrament of Penance and Reconciliation

9. You shall not desire your neighbor’s wife. Am I • If you do not know or cannot remember an Act envious of another’s spouse? Have I consented to of Contrition you may pray: Lord Jesus, Son of Sacrament of Penance impure thoughts? Do I try to control my imagina- God, have mercy on me, a sinner. And tion? Am I reckless and irresponsible in the books I read and the movies I watch? • The priest, acting in the person of Christ, will Reconciliation then absolve you from your sins. 10. You shall not desire your neighbors goods. Am I envious of the possessions of others? Am I re- • After the Absolution, the priest says “Give sentful and bitter over my position in life? thanks to the Lord for he is good.” You re- spond, “His mercy endures forever.” Receiving the Sacrament of Penance • Then the priest will dismiss you by saying “The “Bless me Father, for I have sinned…” Lord has freed you from your sins, go in peace.” The confession (or disclosure) of sins, even from a simply human point of view, frees us and facilitates Act of Contrition our reconciliation with others. Through such an ad- O my God, I am heartily sorry for having offended mission, man looks squarely at the sins he is guilty you, and I detest all my sins because I dread the of; takes responsibility for them; and thereby opens loss of heaven and the pains of hell. But most of himself again to God and to the communion of the all, because I have offended you, my God, who are Church in order to make a new future possible. -

A Guide to the Sacrament of Penance Discover God's Love Anew

A Guide to the Sacrament of Penance Discover God’s Love Anew: Dear Brothers and Sisters in the Lord, Our Holy Father, Pope John Paul II, has asked “for renewed pastoral courage in ensuring that the day-to-day teaching of Christian communities persuasively and effectively presents the practice of the Sacrament of Reconciliation ” (Novo Millennio Ineunte , 37). A renewed appreciation for this wonderful sacrament which leads many to return to the life of grace will bring about a new springtime, a new era of growth and life for the Church. In response to the Pope’s invitation, this statement will speak of our need for reconciliation and explain how we receive it. While we hope that all Catholics properly understand the nature and importance of the sacrament of Penance, this statement is directed in a special way to those who do not understand it or who have drifted away from its use. We invite every Catholic to celebrate the sacrament of Penance or Reconciliation or, as we have traditionally said, “go to Confession,” on a regular basis. There can be no better way to make progress on our spiritual journey than by returning in humble repentance and love to God, whose forgiveness reestablishes us as his children and restores us to peace with his Church and our neighbors. With every prayerful best wish, we remain, Sincerely yours in Christ, The Bishops of Pennsylvania February 2002 (c) 2002 Pennsylvania Catholic Conference, the public affairs agency of Pennsylvania’s Catholic Bishops. For more information, contact PCC at PO Box 2835, Harrisburg, PA 17105 717-238-9613, [email protected], or log on to www.pacatholic.org. -

Solicitation in Confession

WHEN BAD ADVICE IN CONFESSION BECOMES A CRIME The canonical crime of solicitation is likely more widespread than many may suppose. By Dr. Edward N. Peters All would agree that if a given piece of advice is bad in the confessional, then a priest's giving it to a penitent would be, at a minimum, a failure in pastoral care. Depending on circumstances, a priest's proffering of bad advice in confession might even, as a violation of charity or justice, be sinful. But, that the giving of bad advice in confession could be a crime under Church law would be startling. And yet, exactly this reading of Canon 1387 of the 1983 Code of Canon Law is required, I suggest, in light of sound canonical tradition and recent Roman curial norms. Canon 1387 states: "A priest who in the act, on the occasion, or under the pretext of confession solicits a penitent to sin against the sixth commandment of the Decalogue is to be punished, according to the gravity of the delict, by suspension, prohibitions, and privations; in graver cases he is to be dismissed from the clerical state." The image of solicitation that springs to mind here is, of course, that of a priest using the confessional to propose carnal liaisons to a female penitent.l To be sure, such reprehensible behavior is criminalized by Canon 1387. But neither the text of Canon 1387 (specifically the phrase, "solicits a penitent to sin against the sixth commandment of the Decalogue") nor the tradition behind the modern canon construes the crime of solicitation that narrowly. -

Penitence and the English Reformation

Penitence and the English Reformation Thesis is submitted in accordance with the requirements of the University of Liverpool for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Eric Bramhall December 2013 ABBREVIATIONS BL British Library CCC Corpus Christi College, Cambridge CUL Cambridge University Library DCA Denbighshire County Archives ECL Emmanuel College Library, Cambridge EDC Ely Diocesan Records GDR Gloucester Diocesan Records JEH Journal of Ecclesiastical History ODNB Oxford Dictionary of National Biography PRO Public Record Office PS Parker Society RLM Rylands Library, Manchester RSTC Revised Short-Title Catalogue TRHS Transactions of the Royal Historical Society Penitence and the English Reformation Introduction page 1 1 Penitential Practice on the Eve of the Reformation 13 2 Humanists, Penitence and Reformation in Early Sixteenth Century England 27 3 Penitence, Politics and Preachers 1533-1547 61 4 Repentance and Protestants in the Reigns of Edward VI and Mary I 93 5 Penance and the Restoration of the Marian Church 141 6 Penitence and the Elizabethan Church 179 Conclusion 251 Epilogue 257 Bibliography 263 Penitence and the English Reformation INTRODUCTION Penitence was of considerable importance in sixteenth-century England whether it was thought of as auricular confession and the sacrament of penance, or personal repentance and the penitent seeking “suche ghostly counsaill, advyse, and comfort, that his conscience maye be releved.”1 Prior to the Edwardian reforms of the mid-sixteenth century, the sacrament provided an opportunity, with the help of a confessor, for self examination using the seven deadly sins or the Ten Commandments, instruction in the basics of the faith, and the challenge to be reconciled with God and neighbours by performing penitential good works.