The Role of Micro-Generation Technologies in Alleviating Fuel

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Consumer Guide: Balancing the Central Heating System

Consumer Guide: Balancing the central heating system System Balancing Keep your home heating system in good working order. Balancing the heating system Balancing of a heating system is a simple process which can improve operating efficiency, comfort and reduce energy usage in wet central heating systems. Many homeowners are unaware of the merits of system balancing -an intuitive, common sense principle that heating engineers use to make new and existing systems operate more efficiently. Why balance? Balancing of the heating system is the process of optimising the distribution of water through the radiators by adjusting the lockshield valve which equalizes the system pressure so it provides the intended indoor climate at optimum energy efficiency and minimal operating cost. To provide the correct heat output each radiator requires a certain flow known as the design flow. If the flow of water through the radiators is not balanced, the result can be that some radiators can take the bulk of the hot water flow from the boiler, leaving other radiators with little flow. This can affect the boiler efficiency and home comfort conditions as some rooms may be too hot or remain cold. There are also other potential problems. Thermostatic radiator valves with too much flow may not operate properly and can be noisy with water “streaming” noises through the valves, particularly as they start to close when the room temperature increases. What causes an unbalanced system? One cause is radiators removed for decorating and then refitted. This can affect the balance of the whole system. Consequently, to overcome poor circulation and cure “cold radiators” the system pump may be put onto a higher speed or the boiler thermostat put onto a higher temperature setting. -

Microgeneration Strategy: Progress Report

MICROGENERATION STRATEGY Progress Report JUNE 2008 Foreword by Malcolm Wicks It is just over two years since The Microgeneration Strategy was launched. Since then climate change and renewables have jumped to the top of the global and political agendas. Consequently, it is more important than ever that reliable microgeneration offers individual householders the chance to play their part in tackling climate change. In March 2006, there was limited knowledge in the UK about the everyday use of microgeneration technologies, such as solar thermal heating, ground source heat pumps, micro wind or solar photovolatics. Much has changed since then. Thousands of people have considered installing these technologies or have examined grants under the Low Carbon Buildings Programme. Many have installed microgeneration and, in doing so, will have helped to reduce their demand for energy, thereby cutting both their CO2 emissions and their utility bills. The Government’s aim in the Strategy was to identify obstacles to creating a sustainable microgeneration market. I am pleased that the majority of the actions have been completed and this report sets out the excellent progress we have made. As a consequence of our work over the last two years, we have benefited from a deeper understanding of how the microgeneration market works and how it can make an important contribution to a 60% reduction in CO2 emissions by 2050. Building an evidence base, for example, from research into consumer behaviour, from tackling planning restrictions and from tracking capital costs, means that we are now in a better position to take forward work on building a sustainable market for microgeneration in the UK. -

Energy Saving Trust CE131. Solar Water Heating Systems: Guidance For

CE131 Solar water heating systems – guidance for professionals, conventional indirect models Contents 1 Solar hot water systems 3 1.1 Scope 3 1.2 Introduction 3 1.3 Safety 4 1.4 Risk assessment 5 1.5 Town and country planning 5 2 Design overview 6 2.1 Introduction 6 2.2 Solar domestic hot water (SDHW) energy 6 2.3 SDHW systems 7 3 Design detail 8 3.1 Collectors 8 3.2 Solar primary types 9 3.3 Primary system components 10 3.4 Secondary systems 11 3.5 Pre-heat storage 11 3.6 Auxiliary DHW heating 14 3.7 Combined storage – twin-coil cylinders 15 3.8 Separate storage – two stores 15 3.9 Separate storage – direct DHW heaters 16 3.10 Risk of scalding 16 3.11 Risk of bacteria proliferation 17 3.12 Risk of limescale 17 3.13 Energy conservation 18 3.14 Controls and measurement 20 4 Installation and commissioning 23 4.1 Installation tasks: site survey – technical 23 4.2 Installation tasks: selecting specialist tools 28 4.3 Installation tasks: Initial testing 28 4.4 Commissioning 29 5 Maintenance and documentation 30 6 Appendices 31 6.1 Sample commissioning sheet 31 6.2 Annual solar radiation (kWh/m2) 33 6.3 Sample installation checklist 33 6.4 Further reading 37 6.5 Regulations 38 6.6 Other publications 39 7 Glossary 40 The Energy Saving Trust would like to thank the Solar Trade Association for their advice and assistance in producing this publication. 2 Solar water heating systems – guidance for professionals, conventional indirect models 1 Solar hot water systems 1.1 Scope By following the Energy Saving Trust’s best practice This guide is designed to help installers, specifiers and standards, new build and refurbished housing will commissioning engineers ensure that conventional be more energy efficient – reducing these emissions indirect solar domestic hot water systems (SDHW) and saving energy, money and the environment. -

Passive House Cepheus

PASSIVE HOUSE CEPHEUS • The term passive house (Passivhaus in German) refers to the rigorous, voluntary, Passivhaus standard for energy efficiency in buildings. It results in ultra-low energy buildings that require little energy for space heating or cooling. A similar standard, MINERGIE-P, is used in Switzerland. The standard is not confined only to residential properties; several office buildings, schools, kindergartens and a supermarket have also been constructed to the standard. Passive design is not the attachment or supplement of architectural design, but an integrated design process with the architectural design. Although it is mostly applied to new buildings, it has also been used for refurbishments. Thermogram of a Passive house Explain the difference CEPHEUS - Passive Houses in Europe.mht • Passive Houses require superior design and components with respect to: • insulation • design without thermal brigdes • air tightness • ventilation with heat recovery • comfortwindows und • innovative heating technology • To realise an optimal interaction of all components, an energy balance of the building has to be worked out. And step by step any new design may be improved to meat Passive House sta HOW? WALL FLOOR WALL WINDOW Space heating requirement • By achieving the Passivhaus standards, qualified buildings are able to dispense with conventional heating systems. While this is an underlying objective of the Passivhaus standard, some type of heating will still be required and most Passivhaus buildings do include a system to provide supplemental space heating. This is normally distributed through the low- volume heat recovery ventilation system that is required to maintain air quality, rather than by a conventional hydronic or high-volume forced-air heating system, as described in the space heating section below. -

Experience the Calming Beauty of RSF Fireplaces and the Real Wood Fire

2021 Experience the calming beauty of RSF fireplaces and the real wood fire. 1 “Just like Sunday dinner Nothing can replace the warm embrace of a real wood doesn’t come out of fire. A wood fire gives off a special kind of warmth that a can and fine wine penetrates and soothes. It’s true that burning wood in doesn’t come out of a your fireplace isn’t as convenient as burning gas. But box, a real fire doesn’t like all of life’s best things, that little extra effort makes come out of a pipeline.” a world of difference. Just like Sunday dinner doesn’t come out of a can and fine wine doesn’t come out of a box, a real fire doesn’t come out of a pipeline. If it’s a real fire…it’s wood. And if it’s a clean burning efficient wood fire… it’s probably an RSF fireplace. So come in, relax, kick off your shoes and leave your frantic life at the door. Experience the calming beauty of RSF fireplaces and the real wood fire. RSF is a proud supporting member of: 2 Contents 4 The RSF Built-in Advantage 5 The RSF Comfort Advantage 6 The RSF Smart BurnRate Air Control 7 Catalytic or Non-Catalytic Series: Choosing What’s Right for You 8 Focus 3600 Fireplace 10 Pearl 3600 Fireplace 14 Focus SBR Fireplace 16 Delta Fusion Fireplace 18 Opel Keystone Catalytic Fireplace 20 Opel 2 Plus Catalytic Fireplace 22 Opel 3 Plus Catalytic Fireplace 24 Focus ST Fireplace 26 Chimney Safety and Performance 26 RSF Convenience 27 RSF Heat Distribution 29 RSF Performance 29 RSF Accessories 30 RSF Specifications 31 Burning Wood in an RSF Fireplace is Good for the Environment 3 THE RSF THE RSF BUILT-IN ADVANTAGE COMFORT ADVANTAGE A fireplace is one of the most sought after features in a home and will increase its resale value more than a freestanding wood stove. -

Underfloor Heating Systems :///Users//Downloads/ LDS7 FINAL.Pdf

CI/SfB (53) First Issue April 2019 Underfloor Heating Systems :///Users//Downloads/ LDS7_FINAL.pdf SUPERIOR HEATING SOLUTIONS SINCE 1980 2 Firebird Envirofloor™ Underfloor Heating Systems An economical and environmentally friendly alternative to traditional heating and hot water systems. Firebird Products Ltd are market-leading manufacturers of heating products with a proven track record built on the global supply of heating systems. Established in Ireland in 1980, the Firebird name has become synonymous with performance, quality and innovative design. At the forefront of technology, Firebird are committed to providing cost-effective, energy-efficient heating solutions that not only meet, but easily exceed today’s stringent legislative requirements. Historically an oil-fired boiler manufacturer, the product range has been expanded to include air source heat pumps, biomass boilers & stoves, solar thermal systems and underfloor heating systems. @firebirdboilers www.firebird.uk.com 3 Underfloor Heating Systems Underfloor heating is not a new concept and dates back to Roman times when hot gasses from a fire or furnace passed through a network of flues under the floor of the building. From the 1960’s onwards, various modern systems have been introduced which include expensive to run electric underfloor heating and steel pipes, which had expensive material costs. In 1975 plastic underfloor heating pipe was introduced into the UK which greatly reduced the material cost and allowed wider access to this highly efficient way of heating. Suitable for both new build and renovation projects, Envirofloor underfloor heating systems are ‘wet’ underfloor heating is the most efficient way suitable for a wide range of ground and upper to provide space heating as it is up to 25% more floor constructions. -

New Low-Temperature Central Heating System Integrated with Industrial Exhausted Heat Using Distributed Electric Compression Heat Pumps for Higher Energy Efficiency

energies Article New Low-Temperature Central Heating System Integrated with Industrial Exhausted Heat Using Distributed Electric Compression Heat Pumps for Higher Energy Efficiency Fangtian Sun 1,2,*, Yonghua Xie 1, Svend Svendsen 2 and Lin Fu 3 1 Beijing Research Center of Sustainable Energy and Buildings, Beijing University of Civil Engineering and Architecture, Beijing 100044, China; [email protected] 2 Department of Civil Engineering, Technical University of Denmark, 2800 Lyngby, Denmark; [email protected] 3 Department of Building Science, Tsinghua University, Beijing 100084, China; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +86-010-6832-2133; Fax: +86-010-8836-1680 Received: 23 October 2020; Accepted: 9 December 2020; Published: 14 December 2020 Abstract: Industrial exhausted heat can be used as the heat source of central heating for higher energy efficiency. To recover more industrial exhausted heat, a new low-temperature central heating system integrated with industrial exhausted heat using distributed electric compression heat pumps is put forward and analyzed from the aspect of thermodynamics and economics. The roles played by the distributed electric compression heat pumps in improving both thermal performance and financial benefit of the central heating system integrated with industrial exhausted heat are greater than those by the centralized electric compression heat pumps. The proposed low-temperature central heating system has higher energy efficiency, better financial benefit, and longer economical distance of transmitting exhausted heat, and thus, its configuration is optimal. For the proposed low-temperature central heating system, the annual coefficient of performance, annual product exergy efficiency, heating cost, and payback period are about 22.2, 59.4%, 42.83 ¥/GJ, and 6.2 years, respectively, when the distance of transmitting exhausted heat and the price of exhausted heat are 15 km and 15 ¥/GJ, respectively. -

Warmth, Efficiency, and Total Peace of Mind. Combi & Heating Boilers

Warmth, efficiency, and total peace of mind. Combi & Heating Boilers Self-Monitoring Self-Adjusting Self-Commissioning High Efficiency, Wall Mounted, Modulating Condensing Boilers with ”THINK Intelligence Within.” www.baxiboilers.com PN 240012218 Rev. [12/05/19] Why Choose Baxi? In North America, Baxi’s combination heating and domestic hot water boilers were first-to-market, reliably heating homes for almost 2 decades. 98% of customers recommend Baxi Over 8 million boilers produced Best in class ENERGY STAR® ratings at 95% AFUE provide lower utility bills and reduced carbon emissions. Why Choose a Combi Boiler? Combi boilers provide central heating and give you an endless supply of hot water. This means they’re economical to run, as hot water is only produced when you need it. What’s more, there’s no need for a separate water heater. Combi boilers are compact and wall-mounted, saving you valuable space. 150 Plus Years of Founder Richard Baxendale 1866 opened the doors to his new company. The Bermuda, Baxi’s most famous gas-fired boiler was 1966 launched. Celebrated 100th anniversary. A series of acquisitions took 1984 place leading to the ownership of the Bassano del Grappa ++ plant in Italy. Baxi introduced the first high efficiency combi boiler to 2000 North America. The award-winning Baxi #1 2006 Duo-tec Combi high efficiency boiler was launched. Baxi D+R Baxi merged with De Dietrich and Remeha to form BDR 2010 BDR THERMEA Thermea Group. BDR Thermea Group opens 2018 Baxi operations in North America. Innovative Technology Baxi’s pioneering THINK combustion management system provides the installer with the easiest boiler to commission and operate. -

Underfloor Heating

Ø 12-26 mm SYSTEM KAN-therm Underfloor heating Comfort and efficiency EN 2015 TECHNOLOGY OF SUCCESS ISO 9001 About KAN Innovative water and heating solutions KAN was established in 1990 and has been implementing state of the art technologies in heating and water distribution solutions ever since. KAN is a European recognized leader and supplier of state of the art KAN-them solutions and installations intended for indoor hot and cold tap water installations, central heating and floor heating installations, as well as fire extinguishing and technological installations. Since the beginning of its activity, KAN has been building its leading position on such values as professionalism, innovativeness, quality and development. Today, the company employs over 600 people, a great part of which are specialist engineers responsible for ensuring continuous development of the KAN-therm system, all technological processes applied and customerservice. The qualifications and commitment of our personnel guarantees the highest quality of products manufactured in KAN factories. Distribution of the KAN-therm system is performed through a network of commercial partners all over Poland, Germany, Russia, Ukraine, Belarus, Ireland, the Czech Republic, Slovakia, Hungary, Romania and in the Baltic States. Our expansion and dynamic development has proven so effective that KAN-therm labeled products are exported to 23 countries, and our distribution network assumes Europe, a great part of Asia, and a part of Africa. SYSTEM KAN-therm The KAN-therm system is an optimal, complete multipurpose installation system consisting of - special award: state of the art, mutually complementary technical solutions for pipe water distribution installations, Pearl of the highest quality heating installations, as well as technological and fire extinguishing installations. -

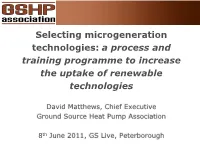

Selecting Microgeneration Technologies: a Process and Training Programme to Increase the Uptake of Renewable Technologies

Selecting microgeneration technologies: a process and training programme to increase the uptake of renewable technologies David Matthews, Chief Executive Ground Source Heat Pump Association 8th June 2011, GS Live, Peterborough UK 2007 Country Number installed Date started Austria 23 000 Canada 36 000 Germany 40 000 1996 Sweden 200 000 1980 Switzerland 25 000 1980 UK 3 000 USA 600 000 1996 • One in 4 to 5 of Swedish homes use a GSHP & Mature markets have codes of practice, standards & training 12% Renewable Heat; Renewable 12% Percentage points increase 2% small scale electricity, 2% small 10% transport scale electricity, 10.0% 12.0% 14.0% 16.0% 0.0% 2.0% 4.0% 6.0% 8.0% UK Denmark total fromof consumption final energy share of in percentage Increase Ireland France Germany Italy Netherlands EU Spain Greece Belgium sources renewable EU Member States Austria Portugal Cyprus Luxembourg Malta 29% large scale electricity, 29% large scale electricity, Finland Sweden Slovenia Hungary Lithuania Poland Slovakia Latvia Estonia Czech Republic Bulgaria Romania UK HP experience Restrictions: • Inconsistent Government policy • Mixed results from HP field trials Drivers: • Renewable Heat Incentive • Government belief – Professor MacKay Professionalism: • MCS • QCF units Metering Heat meter is a flow meter with the temperature difference between flow and return temperature sensors. They have to be Class 2 for RHI. GSHP Boiler Radiant Underfloor Radiators Element Base load About 30 mins Instantaneous Comfortable Mild hot spots Hot skin Socks on floor Scalding rads Burns Combustion • Flame temperature 600 to 900 °C • Downgrade heat to 40 to 80 °C Heat Pump • Collection temperature – 15 to 15 °C • Upgrade heat to 30 to 65 °C n.b. -

Measuring a Heating Systemls Efficiency

45% 57% Space heating is the largest The most common home energy expense in your home, heating fuel is natural gas, accounting for about 45 percent of and it’s used in about 57 percent your energy bills. of American homes. Between 2007 and 2012, the average U.S. household spent more than $700 $1,700 on heating using on heating homes natural gas using heating oil. Before upgrading your heating system, improve the efficiency of your house. This will allow you to purchase a smaller unit, saving you money on the upgrade and operating costs. All heating systems have three basic components. If your heating system isn’t working properly, one of these basic components could be the problem. 68 The heat source -- most The heat distribution The control system -- most commonly a furnace or system -- such as forced air or commonly a thermostat -- boiler -- provides warm air radiators -- moves warm air regulates the amount of to heat the house. through the home. warm air that is distributed. Furnaces and boilers are often called CENTRAL HEATING SYSTEMS because the heat is generated in a central location and then distributed throughout the house. INSTALL A PROGRAMMABLE THERMOSTAT and save big on your energy bills! Save68 an estimated 10 percent a year on heating and cooling costs by using a programmable thermostat. HEAT ACTIVE SOLAR ELECTRIC FURNACES BOILERS PUMPS HEATING HEATING A furnace heats air and uses a A boiler heats water to provide A heat pump pulls heat from the The sun heats a liquid or air in a Sometimes called electric blower motor and air ducts to hot water or steam for heating surrounding air to warm the solar collector to provide resistance heating, electric distribute warm air throughout that is then distributed through house. -

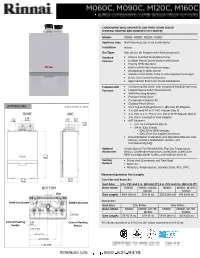

Models M060C, M090C, M120C, M160C Appl

CONDENSING WALL-MOUNTED, GAS-FIRED COMBI BOILER (CENTRAL HEATING AND DOMESTIC HOT WATER) Models M060C, M090C, M120C, M160C Appliance Type Wall-Mounted, Gas-Fired Combi Boiler Installation Indoor Gas Types Natural Gas (or Propane with field conversion) Standard • Factory Installed Modulating Pump Features • Outdoor Reset Control System with Sensor • Priority DHW Standard • Built-in DHW Plate Heat Exchanger • Modulating Ceramic Burner • Stainless Steel Water Tube Condensing Heat Exchanger • Direct Vent Sealed Combustion • Approved for Room and Closet Installations Included with • Condensing Gas Boiler with Integrated Modulating Pump Purchase • Liquid Propane Field Conversion Kit • Wall Mounting Bracket • Pressure Relief Valve • Condensate Collector Kit • Outdoor Reset Sensor Measurements: in. (mm) • Vent Top with Integrated 3 in. (80 mm) PP Adapters • 3 in. (80 mm) PP to 3" PVC Adapter (Qty 2) • 3 in. PVC to 2 in. PVC or 2 in. (60 mm) PP Adapter (Qty 2) • 3 in. X 5 in. Concentric Vent Adapter 4.25 4.44 1.62 3.74 (108) (113) (41) (95) • NPT Adapters: 0.39 (10) − 1 in. for CH Systems (Qty 2) − 3/4 in. (Qty 3 total) ▪ (Qty 2) for DHW Systems ▪ (Qty 1) for Gas Supply Connection • Documentation: Installation and Operation Manual, User Manual, and ISCL (Installation, Service, and Commissioning Log) Optional Closely Spaced Tee/Manifold Kit, Flue Gas Temperature Accessories Sensor, Condensate Neutralizer, ScaleCutter, ScaleCutter 27.56 Refill Cartridge, Boiler Toolkit, and Isolation Valve Kit (700) Venting • Direct Vent (Concentric and Twin Pipe) Options • Room Air • Materials: Polypropylene, Stainless Steel, PVC, CPVC Maximum Equivalent Vent Lengths 17.32 10.46 Twin Pipe and Room Air: (440) (266) Vent Sizes 2 in.