English Department Year 8: ‘Travel Writing’ Knowledge and Content Booklet

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Human Spaceflight in Social Media: Promoting Space Exploration Through Twitter

Human Spaceflight in Social Media: Promoting Space Exploration Through Twitter Pierre J. Bertrand,1 Savannah L. Niles,2 and Dava J. Newman1,3 turn back now would be to deny our history, our capabilities,’’ said James Michener.1 The aerospace industry has successfully 1 Man-Vehicle Laboratory, Department of Aeronautics and Astro- commercialized Earth applications for space technologies, but nautics; 2Media Lab, Department of Media Arts and Sciences; and 3 human space exploration seems to lack support from both fi- Department of Engineering Systems, Massachusetts Institute of nancial and human public interest perspectives. Space agencies Technology, Cambridge, Massachusetts. no longer enjoy the political support and public enthusiasm that historically drove the human spaceflight programs. If one uses ABSTRACT constant year dollars, the $16B National Aeronautics and While space-based technologies for Earth applications are flourish- Space Administration (NASA) budget dedicated for human ing, space exploration activities suffer from a lack of public aware- spaceflight in the Apollo era has fallen to $7.9B in 2014, of ness as well as decreasing budgets. However, space exploration which 41% is dedicated to operations covering the Internati- benefits are numerous and include significant science, technological onal Space Station (ISS), the Space Launch System (SLS) and development, socioeconomic benefits, education, and leadership Orion, and commercial crew programs.2 The European Space contributions. Recent robotic exploration missions have -

Squyres Takes Another Plunge As a NASA Aquanaut 12 June 2012, by Anne Ju

Squyres takes another plunge as a NASA aquanaut 12 June 2012, By Anne Ju translation techniques, and optimum crew size, according to NASA. The crew has substantially changed many of the exploration tools and procedures based on lessons learned from NEEMO 15, Squyres said, which will be tested on the upcoming mission. Also, they will work in tandem with one-person submarines that simulate small free-flying spacecraft at an asteroid -- one of the things NEEMO 15 didn't get to. They'll do the entire mission with a 50-second Steve Squyres, foreground, on a familiarization dive communication delay between Aquarius and the around the Aquarius habitat. With him are fellow outside world to simulate the delays that crews aquanauts Tim Peake and Dottie Metcalf-Lindenburger. would experience on a real asteroid mission, Squyres said. NASA has planned a 2025 mission to an asteroid (Phys.org) -- Mars scientist Steve Squyres is again two-thirds of a mile in size. That mission will be in a learning to walk in space by diving into the sea as microgravity environment, Squyres said. And the a NASA aquanaut. best way to simulate microgravity is under water, he said. Squyres, Goldwin Smith Professor of Astronomy and lead scientist for the NASA Rover mission to Squyres also serves as chairman of the NASA Mars, is one of four NASA scientists making up the Advisory Council. crew of the 16th NASA Extreme Environment Mission Operations (aptly shortened NEEMO), a two-week undersea training mission located in the Provided by Cornell University Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary in Key Largo. -

European Space Agency: Astronaut Recruitment Drive for Greater Diversity

European Space Agency: Astronaut recruitment drive for greater diversity Jonathan Amos Science correspondent @BBCAmoson Twitter The European Space Agency says it wants to recruit someone with a disability as part of its call for new astronauts. Esa will be accepting applications in March to fill four-to-six vacancies in its astro corps but it wants this draft process to be as inclusive as possible. The search for a potential flier with additional functional needs will be run in parallel to the main call. The agency has asked the International Paralympic Committee to advise it on selection. "To be absolutely clear, we're not looking to hire a space tourist that happens also to have a disability," said Dr David Parker, the director of Esa's robotics and human spaceflight programme. "To be very explicit, this individual would do a meaningful space mission. So, they would need to do the science; they would need to participate in all the normal operations of the International Space Station (ISS). "This is not about tokenism," he told BBC News. "We have to be able to justify to all the people who fund us - which is everybody, including people who happen to be disabled - that what we're doing is somehow meaningful to everybody." Individuals with a lower limb deficiency or who have restricted growth - circumstances that have always been a bar in the past - are encouraged to apply. At this stage, the selected individual would be part of a feasibility project to understand the requirements, such as on safety and technical support. But the clear intention is to make "para- astronauts" a reality at some point in the future, even if this takes some time. -

Bringing Space Textiles Down to Earth by Fi Forrest

Feature Bringing Space Textiles Down to Earth By Fi Forrest DOI: 10.14504/ar.19.2.1 extiles are an essential part of the space industry. Every gram sent into orbit costs hundreds of thousands of dol- lars, so textiles must be lightweight as well as strong, and Tresistant to extremes of heat, cold, and ultraviolet radiation that they never have to experience down here on Earth. With the US National Aeronautics and Space Administration’s (NASA) recent announcement of a lunar spaceport—the Gate- way Project—and manned missions to Mars being proposed by Elon Musk, the next generation of space textiles are GO.1,2 In space you find textiles everywhere, from the straps that hold you in place during take-off to the parachute on your re-entry. Diapers are in your underwear, you might work in an inflat- able module on the International Space Station (ISS) and even that flag on the moon was specially designed in nylon. In space everything acts, and reacts, differently. Whether in low-gravity environments like the moon, or micro-gravity on the ISS, even the way moisture wicks away from the human body is different. Disclaimer: Responsibility for opinions expressed in this article is that of the author and quoted persons, not of AATCC. Mention of any trade name or proprietary product in AATCC Review does not constitute a guarantee or warranty of the product by AATCC and does not imply its approval to the exclusion of other products that may also be suitable. March/April 2019 Vol. 19, No. -

ESA Astronaut Tim Peake Arrives in Baikonur on His Last Stop Before Space 1 December 2015

ESA astronaut Tim Peake arrives in Baikonur on his last stop before space 1 December 2015 working on weightless experiments and maintaining the Station as it circles Earth some 400 km up. Tim's Principia mission will see him run experiments for researchers from all over our planet, including trying to grow blood vessels and protein crystals, and using a furnace to melt and cool metal alloys as they float in midair. The two Tims have trained to perform spacewalks and are ready to work together if mission control decides to send them outside. All Soyuz astronauts enjoy a number of traditions before launch, including planting a tree, visiting a ESA astronaut Tim Peake, NASA astronaut Tim Kopra spaceflight museum and signing the door to their and Roscosmos commander Yuri Malenchenko arrived room in the Cosmonaut Hotel. at the Baikonur Cosmodrome in Kazakhstan ahead of their launch to the International Space Station. Credit: Roscosmos ESA astronaut Tim Peake, NASA astronaut Tim Kopra and Roscosmos commander Yuri Malenchenko arrived at the Baikonur Cosmodrome in Kazakhstan today ahead of their launch to the International Space Station. Set for launch on 15 December, the trio will visit their Soyuz TMA-19M spacecraft for the first time tomorrow. The run-up to launch includes preparing ESA astronaut Alexander Gerst took this image circling experiments, numerous medical checkups and Earth on the International Space Station during his six- physical training, as well as reviewing plans for the month Blue Dot mission in 2014. Alexander commented: six-hour flight to the Space Station. " History alive: Yuri Gagarin launched into space from this very place 53 years ago. -

Coronavirus (Covid-19)

Coronavirus (Covid-19) LIVING IN ISOLATION HERE ON EARTH AND AMONG THE STARS LUXEMBOURG, BERLIN, PARIS -- Asteroid Day, the official United Nations’ day of global awareness and education about asteroids and the European Space Agency (ESA) connect Europe and the world with astronauts and celebrities with a message of hope and inspiration. WHEN? Thursday, 26 March; from 16:00 - 21:00 CENTRAL EUROPEAN TIME WHERE? SpaceConnects.Us We can also provide you with a broadcast or web signal of the feed. The world is at a historic standstill. Borders are closing and millions of people are quarantined due to the spread of COVID-19. While we fight this battle and defeat the invisible enemy, solidarity and mutual encouragement are more important for us than ever before. We want to send out a message of unity and hope, join forces and give us, especially our children and youngsters, confidence in our intelligence, our science, ourselves and the place we live in. When we asked space agencies and astronauts whether they could help us to learn how to go far and beyond, how to cope with staggering challenges and find mental and physical practices to live in isolation, the answer was overwhelmingly positive. We are launching a virtual global town hall to exchange with them and all those who are fascinated by space and ready to learn from it. The #SPACECONNECTSUS PROGRAM: Remote sessions with astronauts and guests from all over the world who speak to children, young adults and their families and friends about their experience and techniques in confined places and what else space may provide to help, their trust in science and the sources of their inspiration. -

Three New Crew, Including US Grandpa, Join Space Station 19 March 2016

Three new crew, including US grandpa, join space station 19 March 2016 times in their approximately six-hour journey to the ISS. "Can't believe we just left the planet and we're here already," said Williams, in a call to friends and family gathered back on Earth, which was broadcast online by NASA TV. By the end of his half-year trip aboard the ISS, Williams "will become the American with the most cumulative days in space—534," NASA said. Williams is also now the first American to be a three- time, long-term ISS resident, the US agency said. US astronaut Jeff Williams waves at the Russian-leased Baikonur cosmodrome in Kazakhstan, prior to blasting off to the International Space Station on March 18, 2016 Three new crew members have joined the International Space Station, including a US grandfather who is poised to enter the record books during his time there, NASA said. The Russian spacecraft carrying the astronauts docked at 0309 GMT Saturday some 407 kilometers (253 miles) above the Pacific Ocean, off the western coast of Peru, according to the American space agency. Russian cosmonaut Alexey Ovchinin boards the Soyuz TMA-20M spacecraft at the Russian-leased Baikonur Just over two hours later, crewmates Oleg cosmodrome early on March 19, 2016 Skripochka and Alexey Ovchinin of Russia, plus Jeff Williams, a US grandfather of three who is a veteran of long-duration space missions, floated into the orbital outpost after hatches were opened The rocket took off in windy conditions from to allow their entry. Russia's space base in Kazakhstan at 2126 GMT Friday. -

Reading – Tim Peake Comprehension – 3 Levels with Answers

Tim Peake Who Is Tim Peake? Timothy Nigel ‘Tim’ Peake is a British astronaut who was born in Chichester, West Sussex, England, on 7th April 1972. Tim’s Childhood Tim grew up in a village with his older sister, mother and father. At an early age, Tim was fascinated with flying because his father took him to air shows. He went to school at the Chichester High School for Boys. After Tim Left School • In 1990, Tim went to the Royal Military Academy Sandhurst. • He trained to be a pilot and worked for 18 years for the army. • In 2008, Tim applied to become an astronaut. • In 2009, Tim began his astronaut training at the European Astronaut Corps. Blast Off! In December 2015, Tim Peake launched alongside two other astronauts. Tim reached his destination on the same day. He spent six months living in space. During that time, he completed a spacewalk, which means he left the space station to complete jobs outside in space. This was watched by millions of people on Earth with excitement. Home Again Tim returned to Earth in June 2016, landing in Kazakhstan. During his mission, Tim made 3000 orbits of the Earth. It took two months for Tim’s body to recover from the effects of zero gravity. Did You Know? • Tim’s first meal on board the ISS was a bacon sandwich and cup of tea. • While in space, Tim travelled about 125 million km. • Tim was the first British astronaut to complete a spacewalk. • During Tim’s return to Earth, he travelled at 25 times the speed of sound. -

Tim Gets His Feet Wet 18 April 2012

Tim gets his feet wet 18 April 2012 Spending only a few hours deep underwater requires a safety stop and decompression before coming back up. There is no quick emergency exit from the NEEMO base. NEEMO 11 crewmember in 2006 during a ’waterwalk’ for NASA’s Extreme Environment Mission Operations project (NEEMO). A permanent underwater base almost 20 m below the waves off the coast of Florida allows astronauts to get a feeling of how it is to work and live in space, learning to cope as individuals and as a team in stressful situations. Credits: NASA ESA astronaut Timothy Peake will soon dive to the NEEMO 11 crewmember in 2006 during a ’waterwalk’ bottom of the sea to learn more about exploring for NASA’s Extreme Environment Mission Operations project (NEEMO). A permanent underwater base almost space. A permanent underwater base almost 20 m 20 m below the waves off the coast of Florida allows below the waves off the coast of Florida will be astronauts to get a feeling of how it is to work and live in Tim's home for more than a week in June. space, learning to cope as individuals and as a team in stressful situations. Credits: NASA The NASA Extreme Environment Mission Operations, or NEEMO, allows space agencies to test technologies and research international crew behaviour for long-duration missions. "NEEMO is the best space exploration analogue used in official astronaut training, followed tightly by Astronauts get a feeling of how it is to work and ESA's cave training program," says astronaut live in space, learning to cope as individuals and trainer Loredana Bessone from the European as a team to stressful situations. -

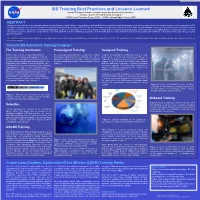

ISS Training Best Practices and Lessons Learned Human Research Program - Human Factors and Behavioral Performance Immanuel Barshi1 (PI) and Donna L

https://ntrs.nasa.gov/search.jsp?R=20170009779 2019-08-31T01:50:58+00:00Z ISS Training Best Practices and Lessons Learned Human Research Program - Human Factors and Behavioral Performance Immanuel Barshi1 (PI) and Donna L. Dempsey2 1NASA, Ames Research Center (ARC) , 2 NASA, Johnson Space Center (JSC) ABSTRACT Training our crew members for long duration exploration-class missions (LDEM) will have to be qualitatively and quantitatively different from current training practices. However, there is much to be learned from the extensive experience NASA has gained in training crew members for missions on board the International Space Station (ISS). Furthermore, the operational experience on board the ISS provides valuable feedback concerning training effectiveness. Keeping in mind the vast differences between current ISS crew training and training for LDEM, the needs of future crew members, and the demands of future missions, this ongoing study seeks to document current training practices and lessons learned. The goal of the study is to provide input to the design of future crew training that takes as much advantage as possible of what has already been learned and avoids as much as possible past inefficiencies. Results from this study will be presented upon its completion. By researching established training principles, examining future needs, and by using current practices in spaceflight training as test beds, this research project is mitigating program risks and generating templates and requirements to meet future training needs. Current ISS Astronaut Training Program The Training Continuum Preassigned Training Assigned Training NASA’s unique expertise in spaceflight training is The preassigned training flow is designed to maintain Assigned crew training for an ISS increment is a multi- extensive and encompasses all aspects of a training proficiency in skills trained in the ASCAN flow until the lateral effort in which each International Partner is program, from the management of training resources, astronaut is assigned to a mission. -

Birmingham Cover Online.Qxp Birmingham Cover 28/09/2016 12:45 Page 1

Birmingham Cover Online.qxp_Birmingham Cover 28/09/2016 12:45 Page 1 Your FREE essential entertainment guide for the Midlands ISSUE 370 OCTOBER 2016 Birmingham RICH HALL ’ COMIC GENIUS’ OUT ON TOUR... WhatFILM I COMEDY I THEATRE I GIGS I VISUAL ARTS I EVENTSs I FOOD On birminghamwhatson.co.uk inside: Yourthe 16-pagelist week by week listings guide CULT MUSICAL COMES TO THE NEW ALEXANDRA THEATRE Alton Towers F/P Oct.qxp_Layout 1 26/09/2016 14:09 Page 1 Contents October Birmingham.qxp_Layout 1 26/09/2016 11:28 Page 1 October 2016 Contents Birmingham Comedy Festival - return of the UK’s longest-running comedy festival page 23 Jean-Michel Jarre Polica Grand Designs the list godfather of electronic music play the Midlands in support of Kevin McCloud hosts leading Your 16-page talks about his world tour latest album, United Crushers contemporary home show week-by-week listings guide Interview page 8 page 15 page 43 page 51 inside: 4. First Word 11. Food 14. Music 20. Comedy 26. Theatre 37. Film 40. Visual Arts 43. Events @whatsonbrum fb.com/whatsonbirmingham @whatsonbirmingham Birmingham What’s On Magazine Birmingham What’s On Magazine Birmingham What’s On Magazine Managing Director: Davina Evans [email protected] 01743 281708 ’ Sales & Marketing: Lei Woodhouse [email protected] 01743 281703 Chris Horton [email protected] 01743 281704 Whats On Matt Rothwell [email protected] 01743 281719 MAGAZINE GROUP Editorial: Lauren Foster [email protected] 01743 281707 Sue Jones [email protected] 01743 281705 Brian O’Faolain [email protected] 01743 281701 Abi Whitehouse [email protected] 01743 281716 Ryan Humphreys [email protected] 01743 281722 Adrian Parker [email protected] 01743 281714 Contributors: Graham Bostock, James Cameron-Wilson, Heather Kincaid, Adam Jaremko, Kathryn Ewing, David Vincent Publisher and CEO: Martin Monahan Accounts Administrator: Julia Perry [email protected] 01743 281717 This publication is printed on paper from a sustainable source and is produced without the use of elemental chlorine. -

Introduction to Esa and the European Space Industry

INTRODUCTION TO ESA AND THE EUROPEAN SPACE INDUSTRY UNITED SPACE IN EUROPE 18 Sept 2019 ESA facts and figures . Over 50 years of experience . 22 Member States . Eight sites/facilities in Europe, about 2300 staff (approx. 5000 total personnel) . 5.72 billion Euro budget (2019) . Over 80 satellites designed, tested and operated in flight Slide 2 Purpose of ESA “To provide for and promote, for exclusively peaceful purposes, cooperation among European states in space research and technology and their space applications.” Article 2 of ESA Convention Slide 3 Member States ESA has 22 Member States: 20 states of the EU (AT, BE, CZ, DE, DK, EE, ES, FI, FR, IT, GR, HU, IE, LU, NL, PT, PL, RO, SE, UK) plus Norway and Switzerland. 7 other EU states have Cooperation Agreements with ESA: Bulgaria, Croatia, Cyprus, Latvia, Lithuania, Malta and Slovakia. Slovenia is an Associate Member. Canada takes part in some programmes under a long-standing Cooperation Agreement. Slide 4 Activities space science human spaceflight exploration ESA is one of the few space agencies in the world to combine responsibility in nearly all areas of space activity. earth observation space transportation navigation * Space science is a Mandatory programme, all Member States contribute to it according to GNP. All other programmes are Optional, funded ‘a la carte’ by Participating States. operations technology telecommunications Slide 5 ESA’s locations Salmijaervi (Kiruna) Moscow Brussels ESTEC (Noordwijk) ECSAT (Harwell) EAC (Cologne) Washington Maspalomas Houston ESA HQ (Paris)