Newly Identified Regulators of Ovarian Folliculogenesis and Ovulation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Oogenesis in Mammals

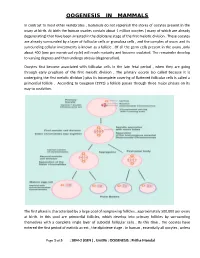

OOGENESIS IN MAMMALS In contrast to most other vertebrates , mammals do not replenish the stores of oocytes present in the ovary at birth. At birth the human ovaries contain about 1 million oocytes ( many of which are already degenerating) that have been arrested in the diplotene stage of the first meiotic division . These oocytes are already surrounded by a layer of follicular cells or granulosa cells , and the complex of ovum and its surrounding cellular investments is known as a follicle . Of all the germ cells present in the ovary ,only about 400 (one per menstrual cycle) will reach maturity and become ovulated. The remainder develop to varying degrees and then undergo atresia (degeneration). Oocytes first become associated with follicular cells in the late fetal period , when they are going through early prophase of the first meiotic division . The primary oocyte (so called because it is undergoing the first meiotic division ) plus its incomplete covering of flattened follicular cells is called a primordial follicle . According to Gougeon (1993) a follicle passes through three major phases on its way to ovulation. The first phase is characterized by a large pool of nongrowing follicles , approximately 500,000 per ovary at birth. In this pool are primordial follicles, which develop into primary follicles by surrounding themselves with a complete single layer of cuboidal follicular cells . By this time , the oocytes have entered the first period of meiotic arrest , the diplotene stage . In human , essentially all oocytes , unless Page 1 of 5 : SEM-2 (GEN ) , Unit#6 : OOGENESIS : Pritha Mondal they degenerate ,remain arrested in the diplotene stage until puberty ; some will not progress past the diplotene stage until the woman’s last reproductive cycle (age 45 to 55 years). -

FEMALE REPRODUCTIVE SYSTEM Female Reproduc�Ve System

Human Anatomy Unit 3 FEMALE REPRODUCTIVE SYSTEM Female Reproducve System • Gonads = ovaries – almond shaped – flank the uterus on either side – aached to the uterus and body wall by ligaments • Gametes = oocytes – released from the ovary during ovulaon – Develop within ovarian follicles Ligaments • Broad ligament – Aaches to walls and floor of pelvic cavity – Connuous with parietal peritoneum • Round ligament – Perpendicular to broad ligament • Ovarian ligament – Lateral surface of uterus ‐ ‐> medial surface of ovary • Suspensory ligament – Lateral surface of ovary ‐ ‐> pelvic wall Ovarian Follicles • Layers of epithelial cells surrounding ova • Primordial follicle – most immature of follicles • Primary follicle – single layer of follicular (granulosa) cells • Secondary – more than one layer and growing cavies • Graafian – Fluid filled antrum – ovum supported by many layers of follicular cells – Ovum surrounded by corona radiata Ovarian Follicles Corpus Luteum • Ovulaon releases the oocyte with the corona radiata • Leaves behind the rest of the Graafian follicle • Follicle becomes corpus luteum • Connues to secrete hormones to support possible pregnancy unl placenta becomes secretory or no implantaon • Becomes corpus albicans when no longer funconal Corpus Luteum and Corpus Albicans Uterine (Fallopian) Tubes • Ciliated tubes – Passage of the ovum to the uterus and – Passage of sperm toward the ovum • Fimbriae – finger like projecons that cover the ovary and sway, drawing the ovum inside aer ovulaon The Uterus • Muscular, hollow organ – supports -

Dental Considerations in Pregnancy and Menopause

J Clin Exp Dent. 2011;3(2):e135-44. Pregnancy and menopause in dentistry. Journal section: Oral Medicine and Pathology doi:10.4317/jced.3.e135 Publication Types: Review Dental considerations in pregnancy and menopause Begonya Chaveli López, Mª Gracia Sarrión Pérez, Yolanda Jiménez Soriano Valencia University Medical and Dental School. Valencia (Spain) Correspondence: Apdo. de correos 24 46740 - Carcaixent (Valencia ), Spain E-mail: [email protected] Received: 01/07/2010 Accepted: 05/01/2011 Chaveli López B, Sarrión Pérez MG, Jiménez Soriano Y. Dental conside- rations in pregnancy and menopause. J Clin Exp Dent. 2011;3(2):e135-44. http://www.medicinaoral.com/odo/volumenes/v3i2/jcedv3i2p135.pdf Article Number: 50348 http://www.medicinaoral.com/odo/indice.htm © Medicina Oral S. L. C.I.F. B 96689336 - eISSN: 1989-5488 eMail: [email protected] Abstract The present study offers a literature review of the main oral complications observed in women during pregnancy and menopause, and describes the different dental management protocols used during these periods and during lac- tation, according to the scientific literature. To this effect, a PubMed-Medline search was made, using the following key word combinations: “pregnant and dentistry”, “lactation and dentistry”, “postmenopausal and dentistry”, “me- nopausal and dentistry” and “oral bisphosphonates and dentistry”. The search was limited to reviews, metaanalyses and clinical guides in dental journals published over the last 10 years in English and Spanish. A total of 38 publi- cations were evaluated. Pregnancy can be characterized by an increased prevalence of caries and dental erosions, worsening of pre-existing gingivitis, or the appearance of pyogenic granulomas, among other problems. -

Inhibition of Gonadotropin-Induced Granulosa Cell Differentiation By

Proc. Nati. Acad. Sci. USA Vol. 82, pp. 8518-8522, December 1985 Cell Biology Inhibition of gonadotropin-induced granulosa cell differentiation by activation of protein kinase C (phorbol ester/diacylglycerol/cyclic AMP/luteinizing hormone receptor/progesterone) OSAMU SHINOHARA, MICHAEL KNECHT, AND KEVIN J. CATT Endocrinology and Reproduction Research Branch, National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD 20892 Communicated by Roy Hertz, August 19, 1985 ABSTRACT The induction of granulosa cell differentia- gesting that calcium- and phospholipid-dependent mecha- tion by follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) is characterized by nisms are involved in the inhibition of granulosa cell differ- cellular aggregation, expression of luteinizing hormone (LH) entiation. The abilities oftumor promoting phorbol esters and receptors, and biosynthesis of steroidogenic enzymes. These synthetic 1,2-diacylglycerols to stimulate calcium-activated actions of FSH are mediated by activation of adenylate cyclase phospholipid-dependent protein kinase C (14, 15) led us to and cAMP-dependent protein kinase and can be mimicked by examine the effects of these compounds on cellular matura- choleragen, forskolin, and cAMP analogs. Gonadotropin re- tion in the rat granulosa cell. leasing hormone (GnRH) agonists inhibit these maturation responses in a calcium-dependent manner and promote phosphoinositide turnover. The phorbol ester phorbol 12- MATERIALS AND METHODS myristate 13-acetate (PMA) also prevented FSH-induced cell Granulosa cells were obtained from the ovaries of rats aggregation and suppressed cAMP formation, LH receptor (Taconic Farms, Germantown, NY) implanted with expression, and progesterone production, with an IDso of 0.2 diethylstilbestrol capsules (2 cm) at 21 days of age and nM. -

6 Ways Your Brain Transforms During Menopause

6 Ways Your Brain Transforms During Menopause By Aviva Patz Movies and TV shows have gotten a lot of laughs out of menopause, with its dramatic hot flashes and night sweats. But the midlife transition out of our reproductive years—marked by yo-yoing of hormones, mostly estrogen—is a serious quality-of-life issue for many women, and as we're now learning, may leave permanent marks on our health. "There is a critical window hypothesis in that what is done to treat the symptoms and risk factors during perimenopause predicts future health and symptoms," explains Diana Bitner, MD, assistant professor at Michigan State University College of Human Medicine and author of I Want to Age Like That: Healthy Aging Through Midlife and Menopause. "If women act on the mood changes in perimenopause and get healthy and take estrogen, the symptoms are much better immediately and also lifelong." (Going through menopause and your hormones are out of whack? Then check out The Hormone Reset Diet to balance your hormones and lose weight.) For many decades, the mantra has been that the only true menopausal symptoms are hot flashes and vaginal dryness. Certainly they're the easiest signs to spot! But we have estrogen receptors throughout the brain and body, so when estrogen levels change, we experience the repercussions all over—especially when it comes to how we think and feel. Two large studies, including one of the nation's longest longitudinal investigations, have revealed that there's a lot going on in the brain during this transition. "Before it was hard to tease out: How much of this is due to the ovaries aging and how much is due to the whole body aging?" says Pauline Maki, PhD, professor of psychiatry and psychology at the University of Illinois at Chicago and Immediate Past President of the North American Menopause Society (NAMS). -

Evolution of Oviductal Gestation in Amphibians MARVALEE H

THE JOURNAL OF EXPERIMENTAL ZOOLOGY 266394-413 (1993) Evolution of Oviductal Gestation in Amphibians MARVALEE H. WAKE Department of Integrative Biology and Museum of Vertebrate Zoology, University of California,Berkeley, California 94720 ABSTRACT Oviductal retention of developing embryos, with provision for maternal nutrition after yolk is exhausted (viviparity) and maintenance through metamorphosis, has evolved indepen- dently in each of the three living orders of amphibians, the Anura (frogs and toads), the Urodela (salamanders and newts), and the Gymnophiona (caecilians). In anurans and urodeles obligate vivi- parity is very rare (less than 1%of species); a few additional species retain the developing young, but nutrition is yolk-dependent (ovoviviparity) and, at least in salamanders, the young may be born be- fore metamorphosis is complete. However, in caecilians probably the majority of the approximately 170 species are viviparous, and none are ovoviviparous. All of the amphibians that retain their young oviductally practice internal fertilization; the mechanism is cloaca1 apposition in frogs, spermato- phore reception in salamanders, and intromission in caecilians. Internal fertilization is a necessary but not sufficient exaptation (sensu Gould and Vrba: Paleobiology 8:4-15, ’82) for viviparity. The sala- manders and all but one of the frogs that are oviductal developers live at high altitudes and are subject to rigorous climatic variables; hence, it has been suggested that cold might be a “selection pressure” for the evolution of egg retention. However, one frog and all the live-bearing caecilians are tropical low to middle elevation inhabitants, so factors other than cold are implicated in the evolu- tion of live-bearing. -

Effect of Insulin-Like Growth Factor-1 (IGF-1) on the Expression of Nfκb and Cflip in Bovine Granulosa Cells

University of New Hampshire University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository Student Research Projects Student Scholarship Spring 2014 Effect of Insulin-Like Growth Factor-1 (IGF-1) on the expression of NFκB and cFLIP in Bovine Granulosa Cells Samantha Kathleen Docos University of New Hampshire - Main Campus Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.unh.edu/student_research Part of the Agriculture Commons, Animal Sciences Commons, Cellular and Molecular Physiology Commons, and the Endocrinology Commons Recommended Citation Docos, Samantha Kathleen, "Effect of Insulin-Like Growth Factor-1 (IGF-1) on the expression of NFκB and cFLIP in Bovine Granulosa Cells" (2014). Student Research Projects. 12. https://scholars.unh.edu/student_research/12 This Undergraduate Research Project is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Student Research Projects by an authorized administrator of University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Effect of Insulin-Like Growth Factor-1 (IGF-1) on the expression of NFκB and cFLIP in Bovine Granulosa Cells Samantha K. Docos, David H. Townson Dept. of Molecular, Cellular and Biomedical Sciences, University of New Hampshire, Durham, NH, 03824 Abstract Materials and Methods Results Continued Isolation of Bovine Granulosa Cells: Ovaries obtained from a slaughter 10 ng/mL IGF-1 100 ng/mL IGF-1 Infertility, often attributed to follicular atresia, is a growing problem in the agricultural industry. house were dissected to obtain follicles 2-5 mm in diameter. The follicles Programmed cell death, also known as apoptosis, is a contributing factor of follicular atresia. -

Luteal Phase Deficiency: What We Now Know

■ OBGMANAGEMENT BY LAWRENCE ENGMAN, MD, and ANTHONY A. LUCIANO, MD Luteal phase deficiency: What we now know Disagreement about the cause, true incidence, and diagnostic criteria of this condition makes evaluation and management difficult. Here, 2 physicians dissect the data and offer an algorithm of assessment and treatment. espite scanty and controversial sup- difficult to definitively diagnose the deficien- porting evidence, evaluation of cy or determine its incidence. Further, while Dpatients with infertility or recurrent reasonable consensus exists that endometrial pregnancy loss for possible luteal phase defi- biopsy is the most reliable diagnostic tool, ciency (LPD) is firmly established in clinical concerns remain about its timing, repetition, practice. In this article, we examine the data and interpretation. and offer our perspective on the role of LPD in assessing and managing couples with A defect of corpus luteum reproductive disorders (FIGURE 1). progesterone output? PD is defined as endometrial histology Many areas of controversy Linconsistent with the chronological date of lthough observational and retrospective the menstrual cycle, based on the woman’s Astudies have reported a higher incidence of LPD in women with infertility and recurrent KEY POINTS 1-4 pregnancy losses than in fertile controls, no ■ Luteal phase deficiency (LPD), defined as prospective study has confirmed these find- endometrial histology inconsistent with the ings. Furthermore, studies have failed to con- chronological date of the menstrual cycle, may be firm the superiority of any particular therapy. caused by deficient progesterone secretion from the corpus luteum or failure of the endometrium Once considered an important cause of to respond appropriately to ovarian steroids. -

Creating an Artificial 3-Dimensional Ovarian Follicle Culture System

micromachines Article Creating an Artificial 3-Dimensional Ovarian Follicle Culture System Using a Microfluidic System Mae W. Healy 1,2, Shelley N. Dolitsky 1, Maria Villancio-Wolter 3, Meera Raghavan 3, Alexandra R. Tillman 3 , Nicole Y. Morgan 3, Alan H. DeCherney 1, Solji Park 1,*,† and Erin F. Wolff 1,4,† 1 Program in Reproductive and Adult Endocrinology, Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD 20892, USA; [email protected] (M.W.H.); [email protected] (S.N.D.); [email protected] (A.H.D.); [email protected] (E.F.W.) 2 Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Walter Reed National Military Medical Center, Bethesda, MD 20889, USA 3 Trans-NIH Shared Resource on Biomedical Engineering and Physical Science, National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD 20892, USA; [email protected] (M.V.-W.); [email protected] (M.R.); [email protected] (A.R.T.); [email protected] (N.Y.M.) 4 Pelex, Inc., McLean, VA 22101, USA * Correspondence: [email protected] † Solji Park and Erin F. Wolff are co-senior authors. Abstract: We hypothesized that the creation of a 3-dimensional ovarian follicle, with embedded gran- ulosa and theca cells, would better mimic the environment necessary to support early oocytes, both structurally and hormonally. Using a microfluidic system with controlled flow rates, 3-dimensional Citation: Healy, M.W.; Dolitsky, S.N.; two-layer (core and shell) capsules were created. The core consists of murine granulosa cells in Villancio-Wolter, M.; Raghavan, M.; 0.8 mg/mL collagen + 0.05% alginate, while the shell is composed of murine theca cells suspended Tillman, A.R.; Morgan, N.Y.; in 2% alginate. -

Androgens Regulate Ovarian Follicular Development by Increasing Follicle Stimulating Hormone Receptor and Microrna-125B Expression

Androgens regulate ovarian follicular development by increasing follicle stimulating hormone receptor and microRNA-125b expression Aritro Sena,b,1, Hen Prizanta, Allison Lighta, Anindita Biswasa, Emily Hayesa, Ho-Joon Leeb, David Baradb, Norbert Gleicherb, and Stephen R. Hammesa,1 aDivision of Endocrinology and Metabolism, Department of Medicine, University of Rochester School of Medicine and Dentistry, Rochester, NY 14642; and bCenter for Human Reproduction, New York, NY 10021 Edited by John J. Eppig, Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME, and approved January 15, 2014 (received for review October 8, 2013) Although androgen excess is considered detrimental to women’s promoting preantral follicle growth and development into an- health and fertility, global and ovarian granulosa cell-specific an- tral follicles. However, these in vivo studies did not elucidate drogen-receptor (AR) knockout mouse models have been used to specific mechanisms used by androgens and ARs to mediate show that androgen actions through ARs are actually necessary these processes. for normal ovarian function and female fertility. Here we describe Here we performed an in-depth analysis of androgen-induced two AR-mediated pathways in granulosa cells that regulate ovar- signaling pathways that regulate ovarian folliculogenesis. Andro- ian follicular development and therefore female fertility. First, we gens signal via extranuclear (nongenomic) and nuclear (genomic) show that androgens attenuate follicular atresia through nuclear pathways. In fact, previous work by others and ourselves in and extranuclear signaling pathways by enhancing expression of androgen-sensitive prostate cancer cells showed that these two the microRNA (miR) miR-125b, which in turn suppresses proapop- processes are tightly linked, with maximal AR-mediated nuclear totic protein expression. -

![Oogenesis [PDF]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2902/oogenesis-pdf-452902.webp)

Oogenesis [PDF]

Oogenesis Dr Navneet Kumar Professor (Anatomy) K.G.M.U Dr NavneetKumar Professor Anatomy KGMU Lko Oogenesis • Development of ovum (oogenesis) • Maturation of follicle • Fate of ovum and follicle Dr NavneetKumar Professor Anatomy KGMU Lko Dr NavneetKumar Professor Anatomy KGMU Lko Oogenesis • Site – ovary • Duration – 7th week of embryo –primordial germ cells • -3rd month of fetus –oogonium • - two million primary oocyte • -7th month of fetus primary oocyte +primary follicle • - at birth primary oocyte with prophase of • 1st meiotic division • - 40 thousand primary oocyte in adult ovary • - 500 primary oocyte attain maturity • - oogenesis completed after fertilization Dr Navneet Kumar Dr NavneetKumar Professor Professor (Anatomy) Anatomy KGMU Lko K.G.M.U Development of ovum Oogonium(44XX) -In fetal ovary Primary oocyte (44XX) arrest till puberty in prophase of 1st phase meiotic division Secondary oocyte(22X)+Polar body(22X) 1st phase meiotic division completed at ovulation &enter in 2nd phase Ovum(22X)+polarbody(22X) After fertilization Dr NavneetKumar Professor Anatomy KGMU Lko Dr NavneetKumar Professor Anatomy KGMU Lko Dr Navneet Kumar Dr ProfessorNavneetKumar (Anatomy) Professor K.G.M.UAnatomy KGMU Lko Dr NavneetKumar Professor Anatomy KGMU Lko Maturation of follicle Dr NavneetKumar Professor Anatomy KGMU Lko Maturation of follicle Primordial follicle -Follicular cells Primary follicle -Zona pallucida -Granulosa cells Secondary follicle Antrum developed Ovarian /Graafian follicle - Theca interna &externa -Membrana granulosa -Antrial -

(12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub. No.: US 2009/0111743 A1 Takahashi (43) Pub

US 200901 11743A1 (19) United States (12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub. No.: US 2009/0111743 A1 Takahashi (43) Pub. Date: Apr. 30, 2009 (54) CYSTEINE-BRANCHED HEPARIN-BINDING Related U.S. Application Data GROWTH FACTOR ANALOGS (60) Provisional application No. 60/656,713, filed on Feb. 25, 2005. (75) Inventor: Kazuyuki Takahashi, O O Germantown, MD (US) Publication Classification (51) Int. Cl. Correspondence Address: A638/08C07K 700 30.82006.O1 201 THIRD STREET, N.W., SUITE 1340 A638/16 (2006.01) ALBUQUEROUE, NM 87102 (US) A638/10 (2006.01) A638/00 (2006.01) (73) Assignee: BioSurface Engineering (52) U.S. Cl. ........... 514/12:530/330; 530/329; 530/328; Technologies, Inc., Rockville, MD 530/327: 530/326; 530/325; 530/324; 514/17; (US) 514/16; 514/15: 514/14: 514/13 (57) ABSTRACT (21) Appl. No.: 11/362,137 The present invention provides a heparin binding growth factor analog of any of formula I-VIII and methods and uses (22) Filed: Feb. 23, 2006 thereof. US 2009/011 1743 A1 Apr. 30, 2009 CYSTENE-BRANCHED HEPARN-BINDING 0007 HBGFs useful in prevention or therapy of a wide GROWTH FACTOR ANALOGS range of diseases and disorders may be purified from natural sources or produced by recombinant DNA methods, however, CROSS-REFERENCE TO RELATED Such preparations are expensive and generally difficult to APPLICATIONS prepare. 0008. Some efforts have been made to generate heparin 0001. This application claims priority to and the benefit of binding growth factor analogs. For example, natural PDGF the filing of U.S. Provisional Patent Application Ser.