Educational Open Government Data in Germany

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

YDO2015 Sponsorfolder V7

6 t/m 11 oktober 2015 YONEX DUTCH OPEN ALMERE Sponsorbrochure RAAK EN BEREIK UW KLANT MET BADMINTON! WELKOM OP DE YONEX DUTCH OPEN ALMERE 2015 DE YONEX DUTCH OPEN WORDT VAN 6 T/M 11 OKTOBER VOOR DE 67e Miljoenen huidshoudingen over de gehele wereld hebben via afspraken met MAAL GEORGANISEERD DOOR BADMINTON NEDERLAND. HET divers mediapartijen naar de wedstrijden van de Yonex Dutch Open 2014 EVENEMENT WORDT VOOR HET 9e JAAR OP RIJ IN HET gekeken. TOPSPORTCENTRUM ALMERE GEORGANISEERD. OOK ZAL VOLGEND Deelnemersveld en ambitie JAAR DE 10e EDITIE PLAATSVINDEN IN ALMERE. Top 20 spelers van de wereld en toekomstige Olympisch medaillewinnaars en wereldkampioenen behoorden in het verleden tot het deelnemersveld van Badminton, van campingsport tot topsport de Yonex Dutch Open. In het gemengddubbel en vrouwendubbel zijn Badminton is een Olympische sport waar snelheid, reflexen en diverse Nederlandse koppels bezig om de Olympische Spelen 2016 in Rio te halen. technieken voor een spannend spel zorgen. Daarnaast is het een toegankelijke De Yonex Dutch Open wil doorgroeien zodat ook top 10 spelers naar familiesport voor jong en oud. Badminton is ook laagdrempelig, het is makkelijk Nederland komen. toe te passen in de zaal, of op het veld, op het strand, tijdens vakantie of als bedrijfsport. Badminton, van campingsport tot topsport. Deze link leggen wij ook Vorig jaar deden 41 verschillende nationaliteiten mee. Deelnemers komen bij ons op topbadminton gerichte Yonex Dutch Open. Geen topsport zonder vanuit de hele wereld naar Topsportcentrum Almere. Naast Europese landen breedtesport. In diverse side-events komt dit tot uiting, zoals bijvoorbeeld de zijn met name Aziatische landen altijd sterk vertegenwoordigd. -

History of Badminton

Facts and Records History of Badminton In 1873, the Duke of Beaufort held a lawn party at his country house in the village of Badminton, Gloucestershire. A game of Poona was played on that day and became popular among British society’s elite. The new party sport became known as “the Badminton game”. In 1877, the Bath Badminton Club was formed and developed the first official set of rules. The Badminton Association was formed at a meeting in Southsea on 13th September 1893. It was the first National Association in the world and framed the rules for the Association and for the game. The popularity of the sport increased rapidly with 300 clubs being introduced by the 1920’s. Rising to 9,000 shortly after World War Π. The International Badminton Federation (IBF) was formed in 1934 with nine founding members: England, Ireland, Scotland, Wales, Denmark, Holland, Canada, New Zealand and France and as a consequence the Badminton Association became the Badminton Association of England. From nine founding members, the IBF, now called the Badminton World Federation (BWF), has over 160 member countries. The future of Badminton looks bright. Badminton was officially granted Olympic status in the 1992 Barcelona Games. Indonesia was the dominant force in that first Olympic tournament, winning two golds, a silver and a bronze; the country’s first Olympic medals in its history. More than 1.1 billion people watched the 1992 Olympic Badminton competition on television. Eight years later, and more than a century after introducing Badminton to the world, Britain claimed their first medal in the Olympics when Simon Archer and Jo Goode achieved Mixed Doubles Bronze in Sydney. -

Peer Review of Germany: Review Report

Peer Review of Germany Review Report 29 July 2020 The Financial Stability Board (FSB) is established to coordinate at the international level the work of national financial authorities and international standard-setting bodies in order to develop and promote the implementation of effective regulatory, supervisory and other financial sector policies. Its mandate is set out in the FSB Charter, which governs the policymaking and related activities of the FSB. These activities, including any decisions reached in their context, shall not be binding or give rise to any legal rights or obligations under the FSB’s Articles of Association. Contact the Financial Stability Board Sign up for e-mail alerts: www.fsb.org/emailalert Follow the FSB on Twitter: @FinStbBoard E-mail the FSB at: [email protected] Copyright © 2020 Financial Stability Board. Please refer to the terms and conditions Table of Contents Foreword ............................................................................................................................... 1 Abbreviations ........................................................................................................................ 2 Executive summary ............................................................................................................... 3 1. Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 6 2. Macroprudential policy framework and tools ................................................................... 7 -

Annual Report Laporan Tahunan 2018

BADMINTON ASSOCIATION OF MALAYSIA ANNUAL REPORT LAPORAN TAHUNAN 2018 1 2 Contents Annual Report 2018 Page Notice of Meeting 5 Minutes of 73rd Annual General Meeting 7 Minutes of the Extra-Ordinary General Meeting 12 Annual Report 16 Sub-Committees Reports • Coaching & Training Committee 28 • Development Committee 44 • Tournament Committee 52 • Technical Officials Committee 60 • Coach Education Panel 66 • Marketing Committee 70 • Media & Communications Committee 78 • Rules, Discipline & Integrity Committee 84 • Building & Facilities Committee 88 • Para-Badminton Committee 98 • Appendices 102 • Audited Accounts 111 3 AFFILIATES Annual Report 2018 PERSATUAN BADMINTON MALAYSIA 4 NOTICE OF MEETING Annual Report 2018 5 NOTICE OF MEETING Annual Report 2018 6 AGM MEETING MINUTES Annual Report 2018 Minit Mesyuarat Agung Tahunan Ke-73 Persatuan Badminton Malaysia / Badminton Association of Malaysia Minutes of 73rd Annual General Meeting Tarikh / Date : 28 April 2018 Masa / Time : 1.00pm Tempat / Venue : Auditorium, Akademi Badminton Malaysia HADIR / PRESENT YH. Dato’ Sri Mohamad Norza Zakaria President YBhg. Dato’ Wira Lim Teong Kiat Deputy President YBhg. Tan Sri Datuk Amar (Dr.) Hj Abdul Aziz Hj. Hussain Deputy President YBhg. Datuk Ng Chin Chai Hon. Secretary Mr. Mohd Taupik Hussain Hon. Asst. Secretary YBhg. Datuk V Subramaniam Hon. Treasurer YBhg. Dato’ Teoh Teng Chor Vice President (Kedah) YBhg. Datuk Dr. Khoo Kim Eng Vice President (Melaka) Mr. David Wee Toh Kiong Vice President (N.Sembilan) Mr. Kah Kau Kiak Vice President (Penang) Mr. Mat Rasid bin Jahlil Vice President (Johor) Dr. Naharuddin Hashim Vice President (Kelantan) Mr. A’amar Hashim Vice President (Perlis) YB Senator Dato’ Sri Khairudin bin Samad Vice President (Putrajaya) Mr. -

Pgasrs2.Chp:Corel VENTURA

Senior PGA Championship RecordBernhard Langer BERNHARD LANGER Year Place Score To Par 1st 2nd 3rd 4th Money 2008 2 288 +8 71 71 70 76 $216,000.00 ELIGIBILITY CODE: 3, 8, 10, 20 2009 T-17 284 +4 68 70 73 73 $24,000.00 Totals: Strokes Avg To Par 1st 2nd 3rd 4th Money ê Birth Date: Aug. 27, 1957 572 71.50 +12 69.5 70.5 71.5 74.5 $240,000.00 ê Birthplace: Anhausen, Germany êLanger has participated in two championships, playing eight rounds of golf. He has finished in the Top-3 one time, the Top-5 one time, the ê Age: 52 Ht.: 5’ 9" Wt.: 155 Top-10 one time, and the Top-25 two times, making two cuts. Rounds ê Home: Boca Raton, Fla. in 60s: one; Rounds under par: one; Rounds at par: two; Rounds over par: five. ê Turned Professional: 1972 êLowest Championship Score: 68 Highest Championship Score: 76 ê Joined PGA Tour: 1984 ê PGA Tour Playoff Record: 1-2 ê Joined Champions Tour: 2007 2010 Champions Tour RecordBernhard Langer ê Champions Tour Playoff Record: 2-0 Tournament Place To Par Score 1st 2nd 3rd Money ê Mitsubishi Elec. T-9 -12 204 68 68 68 $58,500.00 Joined PGA European Tour: 1976 ACE Group Classic T-4 -8 208 73 66 69 $86,400.00 PGA European Tour Playoff Record:8-6-2 Allianz Champ. Win -17 199 67 65 67 $255,000.00 Playoff: Beat John Cook with a eagle on first extra hole PGA Tour Victories: 3 - 1985 Sea Pines Heritage Classic, Masters, Toshiba Classic T-17 -6 207 70 72 65 $22,057.50 1993 Masters Cap Cana Champ. -

Rahmenterminplanung BWF / DBV / Gruppe SO / BWBV Kalenderjahr 2021

Rahmenterminplanung BWF / DBV / Gruppe SO / BWBV Kalenderjahr 2021 Stand : 08.08.2021 WE Jan Feb Mär Apr Mai Jun Jul Aug Sep Okt Nov Dez 02./03. 06./07. 06./07. 03./04. 01./02. 05./06. 03./04. 07./08. 04./05. 02./03. 06./07. 04./05. A-RLT (11/13) Dutch Junior, DMM (BN-Beuel), DM U19, A-RLT (11/13) EM U17, Masters Finale U11 DM U13 (Beuel) A-RLT (11/13) GrSO-MM (BBV) A-RLT (11/13) DM Jun.(BN-Beuel) B-RLT (15/19/SO) BWBV-/C-RLT E/D Bez.-/D-RLT Reg.-/E-RLT Bez.-M. BWBV-M. SpT 01 DM (Bielefeld) Swiss Open, Malaysia Open EM Indonesia Masters Canada Open, Korea Open, Japan Open, Macau Open, WM Spanish Open, GrT GrSO DM Jun.(BN-Beuel) BL SpT E/E(E/E) SaarLorLux Open, BL SpT E/E(E/E), RL SpT E/E RL SpT 17/18 BWBV-M. AK Bez.-MM AK WT 3 BWBV-M. 09./10. 13./14. 13./14. 10./11. 08./09. 12./13. 10./11. 14./15. 11./12. 09./10. 13./14. 11./12. A-RLT (15 E/D) German Junior, A-RLT (15 E/D) A-RLT (11/13), German U17 Open EM U17, WM, GrSO-M. Jun., JtfO Berlin A-RLT (11/13) A-RLT (15 E/M) GrSO-MM (BWBV) Reg.-/E-RLT BWBV-/C-RLT E/M BWBV-/C-RLT E/D BWBV-/C-RLT D/M BWBV-/C-RLT D/M Reg.-/E-RLT Bez.-/D-RLT Reg.-/E-RLT 02 GrSO-M. -

YONEX German Open 2018 GERMAN OPEN INSIDE Samstag, 10

Event-Magazin der YONEX German Open 2018 GERMAN OPEN INSIDE Samstag, 10. März Samstag, 10. März Gabriela und Stefani Stoeva im Halbfinale Lin Dan gegen Ng Ka Long Angus ausgeschieden GERMAN OPEN INSIDE - Samstag 3 Match of the Day 4 - 5 Höhepunkte am Samstag 129 - 13-13 Berichte XXXX und Fotos Viertelfinale 6 - 7 Gabriela und Stefani Stoeva 14 -18 Ergebnisse 8 Foto des Tages 19 Spielplan Halbfinale Die innogy Sporthalle – seit 2005 werden die YONEX German Open in Mülheim an der Ruhr ausgetragen. Ergebnisse und Infos auf YONEX German Open german-open-badminton.de auf Facebook Impressum Herausgeber des Eventmagazins: Hinweise: Vermarktungsgesellschaft Der Herausgeber des Eventmaga- Badminton zins haftet nicht für den Inhalt der Deutschland mbH (VBD) veröffentlichten Anzeigen Südstraße 25a, D-45470 Mülheim an der Ruhr Team: Tel.: 0208/308 2717 Claudia Pauli (cp) E-Mail: janet.bourakkadi @ Katja Süßkraut (ks) vbd-badminton.de Georgios Psaroulakis (gp) Bernd Bauer (bb) Copyright: Sven Heise (sh) Nachdruck, auch auszugsweise, Stephan Wilde (sw) nur mit ausdrücklicher Einwilli- gung des Herausgebers und unter Papier & Druck: voller Quellenangabe Konica Minolta Alexanderstr. 33 45472 Mülheim an der Ruhr Titelfoto: Sven Heise 2 German Open Inside | 10.3.2018 Match of the Day Halbfinale Damendoppel präsentiert vom Sportland Nordrhein-Westfalen 3. Spiel auf Spielfeld 1 Gabriela & Stefani Stoeva – Yuki Fukushima & Sayaka Hirota Herkunftsland: Bulgarien Herkunftsland: Japan Alter: 23 und 22 Jahre Alter: 24 und 23 Jahre Weltranglistenplatz 15 Weltranglistenplatz 4 Ungesetzt bei den YONEX German Open 2018 Setzplatz 3 bei den YONEX German Open 2018 Gabriela und Stefani Stoeva verloren die Im Vorjahr gewannen Yuki Fukushima und bisherigen drei Vergleiche mit den Japane Sayaka Hirota das Finale der YONEX German rinnen – darunter die Begegnung im Viertel Open gegen die Chinesinnen Huang Dong finale der YONEX German Open 2017. -

2020 World Taekwondo Event Calendar

2020 World Taekwondo Event Calendar (subject to change) ※ Grade of event is distinguished by colour: Blue-Kyorugi, Red-Poomsae, Green-Para, Purple-Junior, Orange-Team (as of 7th October, 2020) Date Place Event Discipline Grade Contacts Remarks January 31 - February 1 CADET & JUNIOR N/A (T) +97 155 602 2230 Fujairah, UAE 8th Fujairah Open 2020 (E) [email protected] February 2 SENIOR KYORUGI G-2 [email protected] February 3 SENIOR KYORUGI G-1 (T) +90 530 575 27 00 Istanbul, Turkey 7th Turkish Open February 4 JUNIOR N/A (E) [email protected] February 5 CADET N/A (T) +90 530 575 27 00 February 6-7 Istanbul, Turkey 7th Turkish Open Poomsae POOMSAE G-1 (E) [email protected] (PSS : KPNP) PARA KYORUGI G-1 (T) +52 553 482 2441 sport class: K40, P20, P30 February 7 Puerto Vallarta, Mexico Mexico Para Taekwondo Open (E) [email protected] PARA POOMSAE G-1 February 7 POOMSAE G-1 (T) +52 553 482 2441 Puerto Vallarta, Mexico Mexico Open February 8 SENIOR KYORUGI G-1 (E) [email protected] February 9 CADET & JUNIOR N/A February 7 CADET N/A (T) +96 278 100 0081 February 8 Amman, Jordan 2020 El Hassan Cup JUNIOR N/A (E) [email protected] February 9 SENIOR KYORUGI G-1 February 18-19 Helsingborg, Sweden POOMSAE G-2 (T) +30 211 214 4717 WT President's Cup - Europe February 18-19 SENIOR KYORUGI G-2 (E) [email protected] Helsingborg, Sweden February 20-21 CADET & JUNIOR N/A (T) +46 708 150 631 February 22 SENIOR KYORUGI G-1 Helsingborg, Sweden Helsingborg Open (E) [email protected] February 23 CADET & JUNIOR N/A [email protected] -

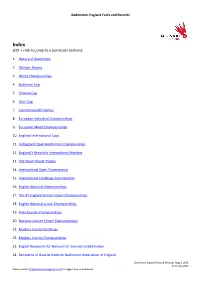

Facts and Records

Badminton England Facts and Records Index (cltr + click to jump to a particular section): 1. History of Badminton 2. Olympic Games 3. World Championships 4. Sudirman Cup 5. Thomas Cup 6. Uber Cup 7. Commonwealth Games 8. European Individual Championships 9. European Mixed Championships 10. England International Caps 11. All England Open Badminton Championships 12. England’s Record in International Matches 13. The Stuart Wyatt Trophy 14. International Open Tournaments 15. International Challenge Tournaments 16. English National Championships 17. The All England Seniors’ Open Championships 18. English National Junior Championships 19. Inter-County Championships 20. National Leisure Centre Championships 21. Masters County Challenge 22. Masters County Championships 23. English Recipients for Honours for Services to Badminton 24. Recipients of Awards made by Badminton Association of England Badminton England Facts & Records: Page 1 of 86 As at May 2021 Please contact [email protected] to suggest any amendments. Badminton England Facts and Records 25. English recipients of Awards made by the Badminton World Federation 1. The History of Badminton: Badminton House and Estate lies in the heart of the Gloucestershire countryside and is the private home of the 12th Duke and Duchess of Beaufort and the Somerset family. The House is not normally open to the general public, it dates from the 17th century and is set in a beautiful deer park which hosts the world-famous Badminton Horse Trials. The Great Hall at Badminton House is famous for an incident on a rainy day in 1863 when the game of badminton was said to have been invented by friends of the 8th Duke of Beaufort. -

Porting an Open Information Extraction System from English to German

Porting an Open Information Extraction System from English to German Tobias Falke† Gabriel Stanovsky‡ Iryna Gurevych† Ido Dagan‡ †Research Training Group AIPHES and UKP Lab Computer Science Department, Technische Universitat¨ Darmstadt ‡Natural Language Processing Lab Department of Computer Science, Bar-Ilan University Abstract on English, with only a few recent exceptions (Zhila and Gelbukh, 2013; Gamallo and Garcia, 2015). For Many downstream NLP tasks can benefit from most languages, Open IE systems are still missing. Open Information Extraction (Open IE) as a While one could create them from scratch, as it was semantic representation. While Open IE sys- tems are available for English, many other done for Spanish, this can be a very laborious pro- languages lack such tools. In this paper, we cess, as state-of-the-art systems make use of hand- present a straightforward approach for adapt- crafted, linguistically motivated rules. Instead, an ing PropS, a rule-based predicate-argument alternative approach is to transfer the rule sets of analysis for English, to a new language, Ger- available systems for English to the new language. man. With this approach, we quickly obtain an Open IE system for German covering 89% of In this paper, we study whether an existing set the English rule set. It yields 1.6 n-ary extrac- of rules to extract Open IE tuples from English de- tions per sentence at 60% precision, making it pendency parses can be ported to another language. comparable to systems for English and readily We use German, a relatively close language, and the usable in downstream applications.1 PropS system (Stanovsky et al., 2016) as examples in our analysis. -

Saving the Open Skies Treaty: Challenges and Possible Scenarios After the U.S

Saving the Open Skies Treaty: Challenges and possible scenarios after the U.S. withdrawal EURO-ATLANTIC SECURITY POLICY BRIEF Dr. Alexander Graef September 2020 The European Leadership Network (ELN) is an independent, non-partisan, pan-European NGO with a network of nearly 200 past, present and future European leaders working to provide practical real-world solutions to political and security challenges. About the author Alexander Graef is a researcher in the project „Arms Control and Emerging Technologies at the Institute for Peace Research and Security Policy at the University of Hamburg (IFSH). He received his PhD in 2019 from the University of St. Gallen (Switzerland) for a thesis on the network of Russian foreign policy experts and think tanks. His current research focuses on conventional arms control and Russian security and defense policy. Support for this publication was provided by a grant from Carnegie Corporation of New York Published by the European Leadership Network, September 2020 European Leadership Network (ELN) 100 Black Prince Road London, UK, SE1 7SJ @theELN europeanleadershipnetwork.org Published under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 © The ELN 2020 The opinions articulated in this report represent the views of the author, and do not necessarily reflect the position of the European Leadership Network or any of its members. The ELN’s aim is to encourage debates that will help develop Europe’s capacity to address pressing foreign, defence, and security challenges. Contents Introduction 1 1. Technical Challenges 2 2. Treaty Implementation and Quotas 9 3. Four Future Scenarios 13 4. Recommendations 15 Introduction expressed at the obligatory state con- ference that convened to discuss the implications of the U.S. -

Evaluation of the German AI Strategy

Evaluation of the German AI Strategy Part 3 www.kas.de Imprint Editor Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung e. V. 2019, Berlin Authors Olaf Groth, Founder and Managing Partner of Cambrian Group Tobias Straube, Principal at Cambrian Group Cambrian LLC, 2381 Eunice Street, Berkeley CA 94708-1644, United States https://cambrian.ai, Twitter: @AICambrian Editorial team and contact at the Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung e. V. Sebastian Weise Consultant for Global Innovation Policy Post: 10907 Berlin Office: Klingelhöferstraße 23 T +49 30 / 269 96-3516 10785 Berlin F +49 30 / 269 96-3551 [Note: This English-language version was translated from the original publication in German.] Cover image: © ABIDAL/sarah5/yongyuan (istockphoto by Getty Images) Images: © Fabio Testa (unsplash) Design and typesetting: yellow too Pasiek Horntrich GbR The print edition was produced in a carbon-neutral way at Druckerei Kern GmbH, Bexbach, and printed on FSC-certified paper. Printed in Germany. Printed with the financial support of the Federal Republic of Germany. This publication is licenced under the terms of “Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International”, CC BY-SA 4.0 (available at: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0/) legalcode.de). ISBN 978-3-95721-571-0 Evaluation of the German AI Strategy Part 3 Olaf Groth, Founder and Managing Partner of Cambrian Group Tobias Straube, Principal at Cambrian Group Table of Contents Background and Definitions 4 Cambrian AI Index © as context for Germany 5 Summary and Evaluation 6 Germany 9 I.) Introduction 9 II.) Requirements for AI 10 III.) Institutional framework 12 IV.) Research and Development 15 V.) Commercialisation 20 Methodology of the Cambrian AI Index © 26 Literature reference 35 Authors 39 Background and Definitions Artificial intelligence: The following definition is used as rapid developments and designs of the a basis for the terminology: initial conceptual AI frameworks.