Manzanitavolume 18, Number 3 • Published by the Friends of the Regional Parks Botanic Garden • Autumn 2014

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hairy) Manzanita (Arcotostaphylos Columbiana

(Hairy) Manzanita (Arcotostaphylos columbiana) RANGE Hairy manzanita is found along the coast from California north to Vancouver Island and the Sunshine Coast. Typically Manzanita is found in the open and in clearings, on shallow, strongly drained soils on rock outcrops and upper slopes. It will tolerate a variety of soil textures and parent materials. Occasionally it is found in open, young Douglas-fir forest. Manzanita does not tolerate deep shade. Photo courtesy of Moralea Milne Manzanita on rock outcrop in Metchosin District HABITAT AND LIFE HISTORY Hairy manzanita is an early colonizer of disturbed plant communities, developing after removal of the forest cover; Manzanita will continue to grow in the understory of an open forest. Black bear, coyote, deer, and various small mammals and birds eat Manzanita fruit. The leaves and stems are unpalatable to browsing wildlife such as deer. Manzanta can flower sporadically throughout several months allowing many invertebrates and hummingbirds to feed on the nectar. Brown elfin butterflies use Manzanita as a host plant, meaning they lay their eggs on Manzanita and the caterpillars use the plant as their food source. DESCRIPTION Hairy Manzanita is an erect or spreading evergreen shrub. It will grow from 1 to 3 metres in height. The bark on mature shrubs is reddish, flaking and peeling, much like arbutus bark. Young twigs and branches are grayish and hairy. Photo courtesy of Will O’Connell. The photo to the right shows the leaves of a young Manzanita on Camas Hill. Leaves are evergreen and egg or oblong shaped. Leaves are grayish and the undersides of leaves are hairy. -

Clearlake Housing Element Update 2014-19 Final

City of Clearlake Housing Element 2014-19 Chapter 8 of the Clearlake 2040 General Plan Adopted on March 26, 2015 City Council Resolution 2015-06 Prepared by: 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS 8.1 Introduction ............................................................................................................................ 3 Purpose ....................................................................................................................................... 3 Housing Element Content and Organization ............................................................................... 3 Data and Methodology ................................................................................................................ 5 Public Participation ..................................................................................................................... 5 8.2 Regulatory Framework........................................................................................................... 7 Authority ...................................................................................................................................... 7 State Housing Goals ................................................................................................................... 7 Recent Legislation ...................................................................................................................... 7 General Plan Internal Consistency ............................................................................................. 8 Regional -

Arctostaphylos: the Winter Wonder by Lili Singer, Special Projects Coordinator

WINTER 2010 the Poppy Print Quarterly Newsletter of the Theodore Payne Foundation Arctostaphylos: The Winter Wonder by Lili Singer, Special Projects Coordinator f all the native plants in California, few are as glass or shaggy and ever-peeling. (Gardeners, take note: smooth- beloved or as essential as Arctostaphylos, also known bark species slough off old “skins” every year in late spring or as manzanita. This wild Californian is admired by summer, at the end of the growing season.) gardeners for its twisted boughs, elegant bark, dainty Arctostaphylos species fall into two major groups: plants that flowers and handsome foliage. Deep Arctostaphylos roots form a basal burl and stump-sprout after a fire, and those that do prevent erosion and stabilize slopes. Nectar-rich insect-laden not form a burl and die in the wake of fire. manzanita blossoms—borne late fall into spring—are a primary food source for resident hummingbirds and their fast-growing Small, urn-shaped honey-scented blossoms are borne in branch- young. Various wildlife feast on the tasty fruit. end clusters. Bees and hummers thrive on their contents. The Wintershiny, round red fruit or manzanita—Spanish for “little apple”— The genus Arctostaphylos belongs to the Ericaceae (heath O are savored by coyotes, foxes, bears, other mammals and quail. family) and is diverse, with species from chaparral, coastal and (The botanical name Arctostaphylos is derived from Greek words mountain environments. for bear and grape.) Humans use manzanita fruit for beverages, Though all “arctos” are evergreen with thick leathery foliage, jellies and ground meal, and both fruit and foliage have plant habits range from large and upright to low and spreading. -

44 Old-Growth Chaparral 12/20

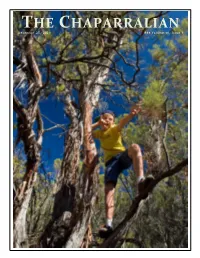

THE CHAPARRALIAN December 25, 2020 #44 Volume 10, Issue 1 2 The Chaparralian #44 Contents 3 The Legacy of Old-Growth Chaparral 4 The Photography of Chaparralian Alexander S. Kunz 8 A New Vision for Chaparral 11 The Dance Between Arctostaphylos and Ceanothus 14 Unfoldings Cover photograph: A magnificent old-growth red shanks or ribbonwood (Adenostoma sparsifolium) with a chaparral elf exploring its The Chaparralian is the periodic journal of the California Chaparral branches. Photo taken in the Descanso Ranger Institute, a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization dedicated to the District, Cleveland National Forest, by Richard preservation of native shrubland ecosystems and supporting the W. Halsey. creative spirit as inspired by Nature. To join the Institute and receive The Chaparralian, please visit our website or fill out and Photo upper left: Old-growth manzanita in The mail in the slip below. We welcome unsolicited submissions to the fabulous Burton Mesa Ecological Preserve, Chaparralian. Please send to: [email protected] or via near Lompoc, CA. The reserve is a 5,368-acre post to the address below. protected area, managed by the California Department of Fish and Wildlife. In this photo, You can find us on the web at: https://californiachaparral.org/ an ephemeral Chaparrailan enjoys the ancient, twisting branches of the rare, endemic Purisima Publisher................................... Richard W. Halsey manzanita (Arctostaphylos purissima). Photo by Editor....................................... Dylan Tweed Richard W. Halsey. Please Join the California Chaparral Institute and support our research and educational efforts to help promote a better understanding of and appreciation for the remarkable biodiversity found in shrubland ecosystems and to encourage the creative spirit as inspired by Nature. -

Arbutus (Arbutus Menziesii)

Arbutus (Arbutus menziesii) RANGE The Arbutus (known as madrone in the U.S.) is one of the most unique trees of Canada’s west coast. It is found from Mexico to southern Vancouver Island. In British Columbia it is found within about 8 kilometres of the shorelines of the Straits of Juan de Fuca and Georgia. It is usually found on exposed rocky bluffs overlooking the ocean, but the tree will grow well on deeper soils as well. Arbutus have been found as far north as Quadra Island and Discovery Passage and on the west coast of Vancouver Island at the head of Nootka Sound. HABITAT AND LIFE HISTORY The Arbutus needs little in the way of tender loving care. The tree is found on very dry, excessively drained sites, such as exposed rock and rocky soils. It loves the sun and has adapted to survive the prolonged summer dry spells of southern Vancouver Island. The arbutus is a very useful for erosion control on disturbed sites. Rufous Hummingbirds and bees are both attracted to the flowers. The berries are food for waxwings, robins, thrushes, band-tailed pigeons, and woodpeckers. Secondary cavity nesters such as tree swallows use the natural cavities created by broken branches for nest sites. Arbutus may be associated with other species such as Garry Oak, Douglas-fir, oceanspray, salal or Oregon-grape. The rare mushroom, Tubaria punicea (Christmas naucoria) only grow from the hollowed and rotting centres of ancient arbutus trees. These dark red mushrooms of late fall and early winter have been found on arbutus trees in Metchosin. -

Pdf (286 KB) (Listed Under the Name Raven’S Manzanita)

U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service Sacramento Fish & Wildlife Office Species Account PRESIDIO MANZANITA Arctostaphylos hookeri ravenii CLASSIFICATION: Endangered Federal Register Notice 44:61911; October 26, 1979 http://ecos.fws.gov/docs/federal_register/fr343.pdf (286 KB) (Listed under the name Raven’s manzanita) STATE LISTING STATUS AND CNPS CODE: This species was listed as endangered by the California Department of Fish and Game in November 1978. The California Native Plant Society has placed it on List 1B (rare or endangered throughout its range). Presidio Manzanita Jo-Ann Ordano CRITICAL HABITAT : None designated 2005 California Academy of Sciences RECOVERY PLAN : Recovery Plan for Coastal Plants of the Northern San Francisco Peninsula http://ecos.fws.gov/docs/recovery_plan/031006.pdf 5-YEAR REVIEW : None DESCRIPTION: Presidio manzanita (also known as Raven’s Manzanita) is a prostrate to ascending evergreen shrub in the heath family (Ericaceae). It was reported to grow less than 60 centimeters (2 feet) tall in historic inland, but the single wild plant today grows nearly prostrate on an exposed coastal site. Presidio manzanita’s leathery, evergreen, round to round-elliptic leaves are 1 to 2 centimeters (0.3 to 0.7 inch) long, and are isofacial (have the same type of surface on both sides). Presidio Manzanita © 2003 David Graber Flowers are urn-shaped to round, with five-lobed white to pinkish corollas 4 to 5 millimeters (about 0.25 inch) long. Flowers appear from mid- winter (in mild winters) to mid-spring. Fruits are tan or brownish, round, and berry-like with thick pulp, containing 2 to 10 stony seeds. -

Arctostaphylos Uva-Ursi (L.) Spreng

Scientific Name: Arctostaphylos uva-ursi (L.) Spreng. Family: Ericaceae Common Names: bearberry, kinnikinnick, red bearberry, cowberry, manzanita, mealberry Fruit: Mealy (not juicy) drupe with dry, shell-like skin; 6 to 8 mm diameter, spherical, dull red. Seed: 5 to 6 seeds in a generally united round stone, individual 3.5 x 2 mm, sectioned, rough, porous, yellow brown. Habitat and Distribution Prefers rocky, open woodlands, dry, sandy hills and pine forest (Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center 2013). It is adapted to coarse and medium textured soils; has moderate carbonate tolerance and is highly drought tolerant. Can handle pH from 5.5 to 8.0, medium salinity and prefers intermediate shade (USDA NRCS n.d.). Seral Stage: Early, recovers well after fire (Crane 1991, Tannas 1997). Soils: Sandy and well-drained sites in woodlands and throughout the prairie, roadside, exposed rocks. Relatively low shade tolerance. Moderate acid tolerance. Tolerant to a wide range of soil textures. Common on coarse and well drained soils. Preference to gravely and sandy loams (Hardy BBT 1989). Arctostaphylos uva-ursi a. plant habit including flowering branch, leaves and roots b. arrangement of flowers in the inflorescence c. flower d. flower (cut away) e – g. seed. Plant Description Trailing evergreen perennial shrub 7.5 to 10 cm tall; forms mats with prostrate and rooting branches 50 to 100 cm long; alternate leaves, coriaceous, obovate to spatulate 1 to 2 cm long; 1 to 3 cm long drooping urn- shaped flowers nodding in a dense raceme (3 to 10); rhizomatous with nodal feeder roots that form in the second years (Moss 1983). -

Mt. Diablo Manzanita (Arctostaphylos Auriculata)

Plants Mount Diablo Manzanita (Arctostaphylos auriculata) Mount Diablo Manzanita (Arctostaphylos auriculata) Status Federal: None State: None CNPS: List 1B Population Trend Global: Unknown © 1967 California Native Plant Society State: Unknown Within Inventory Area: Unknown Data Characterization The location database for Mount Diablo manzanita (Arctostaphylos auriculata) includes 19 data records dated from 1889 to 1995 (California Natural Diversity Database 2005). Only 2 occurrences were documented in the last 10 years, but all occurrences except 1 are believed to be extant (California Natural Diversity Database 2005). Fifteen of the occurrences are of high precision and may be accurately located within the inventory area. Very little ecological information on Mount Diablo manzanita is available. The literature on the species pertains primarily to its taxonomy. The main sources of general information are the Jepson Manual (Hickman 1993) and the California Native Plant Society (2005). Specific observations on habitat and plant associates, threats, and other factors are summarized in the California Natural Diversity Database (2005). Range Mount Diablo manzanita is endemic to Contra Costa County, where it occurs only on Mount Diablo and in the adjacent foothills. It is found between 700 and 1,860 feet above sea level. Occurrences within the ECCC HCP/NCCP Inventory Area Fourteen occurrences of Mount Diablo manzanita are known within the inventory area (12 of these have locational data). Ten of these occurrences are in Mount Diablo State Park, on East Bay Regional Park District lands, or on other public lands. Species Accounts ♦ Plants October 2006 East Contra Costa County HCP/NCCP 1 Plants Mount Diablo Manzanita (Arctostaphylos auriculata) Biology Physical Description Mount Diablo manzanita is an evergreen, perennial shrub, generally between 1 and 4.5 meters tall (Hickman 1993). -

Rare Plants of San Francisco County

RARE PLANTS OF SAN FRANCISCO COUNTYa Published in 2019 by the Yerba Buena Chapter of the California Native Plant Society, Rare Plant Committee - http://cnps-yerbabuena.org & the San Francisco Department of the Environment - sfenvironment.org/biodiversity g Habit c Flowering Common [Synonymy] / notes f SF is Type Geographic Family e Habitat Scientific Nameb Name rarity statusd Periodh Locality Limit note SF Occurrences duration life form Arabis coast rock Brassicaceae - Rarity status: --/--/4.3 h p 12 Mar–Apr Yes rocky cliffs blepharophylla cress Mustard Family [A. hookeri ssp. f.] Reported from Arctostaphylos Franciscan Ericaceae - Heath Doyle Dr.and WWII Memorial. endemic to s p evergreen 1 Jan–Apr serpentine franciscana manzanita Family Historically occurred at Mt. Davidson. SF Rarity status: E/--/1B.1 [A. hookeri ssp. r.] Not in Howell, et Arctostaphylos al. Reported from Doyle Dr.and Presidio Ericaceae - Heath endemic to montana ssp. Coastal Bluffs. Historically occurred at s p evergreen 1 Feb–Apr Yes serpentine manzanita Family SF ravenii Mt. Davidson. Rarity status: E/E/1B.1 Chorizanthe San Francisco Polygonaceae - cuspidata ssp. Rarity status: --/--/1B.2 h a 10 Apr–Jul Yes sandy soil spineflower Buckwheat Family cuspidata Reported only from Baker Beach bluffs, ravines, Cirsium Franciscan Asteraceae - southern North, Coastal Bluff, and Fort Point h b/p 3 May–Sep Yes seeps, occasionally andrewsii thistle Sunflower Family limit on coast Bluffs. Rarity status: --/--/1B.2 on serpentine Onagraceae - Reported only from Inspiration Point endemic to Clarkia Presidio Evening-Primrose and WWII Memorial. h a 2 May–Jun Yes SF and serpentine grassland franciscana clarkia Family Rarity status: E/E/1B.1 Oakland Previously in the Scrophulariaceae. -

Manzanitas (Arctostaphylos Species) Known to Be Susceptible to Phytophthora Ramorum

April 3, 2020 Manzanitas (Arctostaphylos species) known to be susceptible to Phytophthora ramorum (Many of the species listed below are not yet on the USDA APHIS P. ramorum proven host or associated host list.) Arctostaphylos columbiana (bristly manzanita, hairy manzanita) – On the USDA APHIS P. ramorum associated host list. First reported in February 2006 by Rizzo, UC Davis (DiLeo et al. 2008). Arctostaphylos columbiana is native to the Pacific coast from northern California to British Columbia. Hairy manzanita is often available at native plant and horticultural nurseries. Arctostaphylos glandulosa (Eastwood's manzanita) – First reported with P. ramorum symptoms on Mt. Tamalpais in June 2015 (Rooney-Latham et al. 2017). Arctostaphylos glandulosa is native to the Pacific coast from Baja California to southern Oregon, and includes eleven subspecies (adamsii, atumescens, crassifolia, cushingiana, erecta, gabrielensis, glandulosa, howellii, juarezensis, leucophylla, mollis). Arctostaphylos glandulosa subsp. crassifolia (Del Mar manzanita) is listed as rare, threatened, or endangered in California and elsewhere (CA RPR 1B.1). Arctostaphylos glandulosa subsp. gabrielensis (San Gabriel manzanita) is listed as rare, threatened, or endangered in California and elsewhere (CA RPR 1B.2) and as Sensitive Species for both Bureau of Land Management and U.S. Forest Service. Eastwood's manzanita is often available at native plant nurseries. Arctostaphylos glauca (bigberry manzanita) – First reported as a P. ramorum host by Rooney- Latham and Blomquist, CDFA (publication in prep, 2020). Arctostaphylos glauca is native to California and Baja California, where it grows in chaparral and woodland ecosystems. Bigberry manzanita is often available at nurseries. Cultivars include 'Blue Corgi', 'Dwaine's Dwarf', ' Frazier Park Manzanita', ' Los Angeles', 'Margarita Pearl', ' Ramona'. -

Klamath Mountains Ecoregion

Ecoregions: Klamath Mountains Ecoregion Photo © Bruce Newhouse Klamath Mountains Ecoregion Getting to Know the Klamath Mountains Ecoregion example, there are more kinds of cone-bearing trees found in the Klam- ath Mountains ecoregion than anywhere else in North America. In all, The Oregon portion of the Klamath Mountains ecoregion covers much there are about 4000 native plants in Oregon, and about half of these of southwestern Oregon, including the Umpqua Mountains, Siskiyou are found in the Klamath Mountains ecoregion. The ecoregion is noted Mountains and interior valleys and foothills between these and the as an Area of Global Botanical Significance (one of only seven in North Cascade Range. Several popular and scenic rivers run through the America) and world “Centre of Plant Diversity” by the World Conserva- ecoregion, including: the Umpqua, Rogue, Illinois, and Applegate. tion Union. The ecoregion boasts many unique invertebrates, although Within the ecoregion, there are wide ranges in elevation, topography, many of these are not as well studied as their plant counterparts. geology, and climate. The elevation ranges from about 600 to more than 7400 feet, from steep mountains and canyons to gentle foothills and flat valley bottoms. This variation along with the varied marine influence support a climate that ranges from the lush, rainy western portion of the ecoregion to the dry, warmer interior valleys and cold snowy mountains. Unlike other parts of Oregon, the landscape of the Klamath Mountains ecoregion has not been significantly shaped by volcanism. The geology of the Klamath Mountains can better be described as a mosaic rather than the layer-cake geology of most of the rest of the state. -

Manzanitas, California's “Little Apples”

MANZANITAS, CALIFORNIA’S “LITTLE APPLES” THE GENUS ARCTOSTAPHYLOS AND ITS HORTICULTURAL POTENTIAL AND DIVERSITY The manzanitas are centered in California, with over 90% of the species found nowhere else in the world • Only one species, A. uva-ursi or bearberry occurs outside North America; that species is found all across the Northern Hemisphere • Although belonging to the heather family, Ericaceae, manzanitas are best adapted to summer-dry, hot climates, whereas most other ericoids prefer cool, humusy, partly shady conditions in acid soils • Manzanitas vary in form from low woody ground covers only inches high to shrubs and even small trees up to 20 feet tall Manzanitas can be recognized by the following traits: • Red to red-purple bark filled with tannins • Evergreen lance-shaped to ovate, usually entire leaves that are often vertically oriented • Drooping clusters of white to deep pink, urn-shaped flowers, • Berrylike reddish fruits with a mealy pulp and bone-hard seeds often partly fused together • Some species form expanded root crowns or burls from which they stump sprout when injured • All attract widllife to feed on the fruits and sip nectar from the flowers although the “legitimate” pollinators are tiny native bees that can squeexe inside the flowers Manzanita flowers have 5 tiny sepals, 5 petals (seldom 4) fused into an urn with tiny lobes at the tip, 10 stamens that open by pores at the anther tips and have pronglike appendages, and a superior ovary. Here is a cut-away view of the inside of manzanita flowers Here is what a burl looks like on Eastwood manzanita, A.