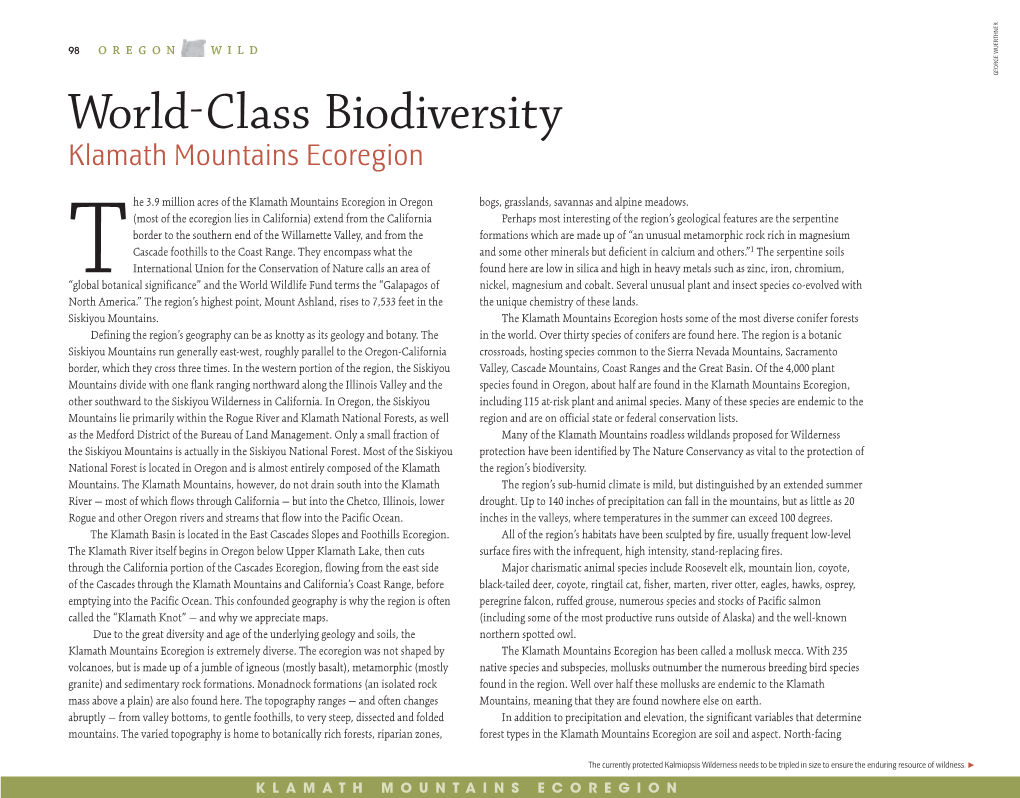

Klamath Mountains Ecoregion

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Strategy Habitat: Ponderosa Pine Woodlands

Habitat: Conservation Summaries for Strategy Habitats Strategy Habitat: Ponderosa Pine Woodlands Ecoregions: Conservation Overview: Ponderosa Pine Woodlands are a Strategy Habitat in the Blue Moun- Ponderosa pine habitats historically covered a large portion of the tains, East Cascades, and Klamath Mountains ecoregions. Blue Mountains ecoregion, as well as parts of the East Cascades and Klamath Mountains. Ponderosa pine is still widely distributed in eastern Characteristics: and southern Oregon. However, the structure and species composition The structure and composition of ponderosa pine woodlands varies of woodlands have changed dramatically. Historically, ponderosa pine across the state, depending on local climate, soil type and moisture, habitats had frequent low-intensity ground fires that maintained an elevation, aspect and fire history. In Blue Mountains, East Cascades open understory. Due to past selective logging and fire suppression, and Klamath Mountains ecoregions, ponderosa pine woodlands have dense patches of smaller conifers have grown in the understory of pon- open canopies, generally covering 10-40 percent of the sky. Their derosa pine forests. Depending on the area, these conifers may include understories are variable combinations of shrubs, herbaceous plants, shade-tolerant Douglas-fir, grand fir and white fir, or young ponderosa and grasses. Ponderosa woodlands are dominated by ponderosa pine, pine and lodgepole pine. These dense stands are vulnerable to drought but may also have lodgepole, western juniper, aspen, western larch, stress, insect outbreaks, and disease. The tree layers act as ladder fuels, grand fir, Douglas-fir, incense cedar, sugar pine, or white fir, depend- increasing the chances that a ground fire will become a forest-destroy- ing on ecoregion and site conditions. -

North Cascades Contested Terrain

North Cascades NP: Contested Terrain: North Cascades National Park Service Complex: An Administrative History NORTH CASCADES Contested Terrain North Cascades National Park Service Complex: An Administrative History CONTESTED TERRAIN: North Cascades National Park Service Complex, Washington An Administrative History By David Louter 1998 National Park Service Seattle, Washington TABLE OF CONTENTS adhi/index.htm Last Updated: 14-Apr-1999 http://www.nps.gov/history/history/online_books/noca/adhi/[11/22/2013 1:57:33 PM] North Cascades NP: Contested Terrain: North Cascades National Park Service Complex: An Administrative History (Table of Contents) NORTH CASCADES Contested Terrain North Cascades National Park Service Complex: An Administrative History TABLE OF CONTENTS Cover Cover: The Southern Pickett Range, 1963. (Courtesy of North Cascades National Park) Introduction Part I A Wilderness Park (1890s to 1968) Chapter 1 Contested Terrain: The Establishment of North Cascades National Park Part II The Making of a New Park (1968 to 1978) Chapter 2 Administration Chapter 3 Visitor Use and Development Chapter 4 Concessions Chapter 5 Wilderness Proposals and Backcountry Management Chapter 6 Research and Resource Management Chapter 7 Dam Dilemma: North Cascades National Park and the High Ross Dam Controversy Chapter 8 Stehekin: Land of Freedom and Want Part III The Wilderness Park Ideal and the Challenge of Traditional Park Management (1978 to 1998) Chapter 9 Administration Chapter 10 http://www.nps.gov/history/history/online_books/noca/adhi/contents.htm[11/22/2013 -

Chetco River

SIXES RIVER WATERSHED ASSESSMENT Prepared for The Sixes River Watershed Council Prepared by Mike Maguire South Coast Watershed Council June 2001 South Coast Watershed Council PO Box 666 Gold Beach, Oregon 97444 (541) 247-2755 TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT AND ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS……………………………………...…i INTRODUCTION AND PURPOSE………………………………………………..…..ii I WATERSHED CHARACTERIZATION………………………….…………..1 INTRODUCTION AND SUBWATERSHEDS……………………..………………………..…1-2 LAND OWNERSHIP AND USE………………………………………………………………..2-3 II WATERSHED ISSUES………………………………………………………….5 BACKGROUND, INTRODUCTION AND RESULTS…………………………………………..5 III ECOREGIONS………………………………………………………………..…6 BACKGROUND AND INTRODUCTION……………………………………………..……....6-7 DESCRIPTION OF ECOREGIONS…………………………………………………………...7-11 IV CHANNEL HABITAT TYPES……………………………………………..…12 BACKGROUND……………………………………………………………………………..…..12 INTRODUCTION AND METHODOLOGY………….……………………………………..12-13 CHANNEL SENSITIVITY / RESPONSIVENESS…………………………………………..13-14 DESCRIPTION OF CHANNEL HABITAT TYPES………………………...………………15-25 RESULTS……………………………………………………………………………….…….26-27 KEY FINDINGS……………………………………………………………………………...27-28 V FISH & FISH HABITAT…..…………………………………………………..29 BACKGROUND……………………………………………………………………………...29-33 INTRODUCTION…………………………………………………………………………….33-38 KEY FINDINGS…………………………………………………………………………….……38 VI WATER QUALITY…………………………………………………………….40 BACKGROUND……………………………………………………………………………...40-43 INTRODUCTION…………………………………………………………………………….43-45 METHODOLOGY……………………………………..……………………………………..45-46 RESULTS……………………………………………………………………………………..46-49 KEY FINDINGS………………………………………………..………………………….....49-50 -

1922 Elizabeth T

co.rYRIG HT, 192' The Moootainetro !scot1oror,d The MOUNTAINEER VOLUME FIFTEEN Number One D EC E M BER 15, 1 9 2 2 ffiount Adams, ffiount St. Helens and the (!oat Rocks I ncoq)Ora,tecl 1913 Organized 190!i EDITORlAL ST AitF 1922 Elizabeth T. Kirk,vood, Eclttor Margaret W. Hazard, Associate Editor· Fairman B. L�e, Publication Manager Arthur L. Loveless Effie L. Chapman Subsc1·iption Price. $2.00 per year. Annual ·(onl�') Se,·ent�·-Five Cents. Published by The Mountaineers lncorJ,orated Seattle, Washington Enlerecl as second-class matter December 15, 19t0. at the Post Office . at . eattle, "\Yash., under the .-\0t of March 3. 1879. .... I MOUNT ADAMS lllobcl Furrs AND REFLEC'rION POOL .. <§rtttings from Aristibes (. Jhoutribes Author of "ll3ith the <6obs on lltount ®l!!mµus" �. • � J� �·,,. ., .. e,..:,L....._d.L.. F_,,,.... cL.. ��-_, _..__ f.. pt",- 1-� r�._ '-';a_ ..ll.-�· t'� 1- tt.. �ti.. ..._.._....L- -.L.--e-- a';. ��c..L. 41- �. C4v(, � � �·,,-- �JL.,�f w/U. J/,--«---fi:( -A- -tr·�� �, : 'JJ! -, Y .,..._, e� .,...,____,� � � t-..__., ,..._ -u..,·,- .,..,_, ;-:.. � --r J /-e,-i L,J i-.,( '"'; 1..........,.- e..r- ,';z__ /-t.-.--,r� ;.,-.,.....__ � � ..-...,.,-<. ,.,.f--· :tL. ��- ''F.....- ,',L � .,.__ � 'f- f-� --"- ��7 � �. � �;')'... f ><- -a.c__ c/ � r v-f'.fl,'7'71.. I /!,,-e..-,K-// ,l...,"4/YL... t:l,._ c.J.� J..,_-...A 'f ',y-r/� �- lL.. ��•-/IC,/ ,V l j I '/ ;· , CONTENTS i Page Greetings .......................................................................tlristicles }!}, Phoiitricles ........ r The Mount Adams, Mount St. Helens, and the Goat Rocks Outing .......................................... B1/.ith Page Bennett 9 1 Selected References from Preceding Mount Adams and Mount St. -

Little Applegate Hydrology Report

Little Applegate Watershed Hydrology Report Michael Zan * Hydrologist April 1995 Little Applegate Watershed Analysis Hydrology Report SECTION 1 LITTLE APPLEGATE RIVER HYDROLOGY Mean Monthly Flows: Except for some data collected from May through October 1913, and from June through October 1994. there is no known flow data for the Little Applegate River or its tributaries. With this in mind it was necessary to construct a hydrograph displaying mean monthly flows by utilizing records from nearby stations that have been published in USGS Surface Water Records and Open-File Reports. In constructing a hydrograph, a short discussion of low flows is first in order. Since low streamflows have been identified as a key question pertaining to the larger issues of water quantity/quality and fish populations, the greatest need is to gain a reasonable estimate of seasonal low flows to help quantify the impacts of water withdrawals on instream beneficial uses. With this in mind, extreme caution must be used when extrapolating data from gaged to ungaged watersheds. This is particularly important in determining low-flow characteristics (Riggs 1972, Gallino 1994 personal communications). The principle terrestrial influence on low flow is geology and the primary meteorological influence is precipitation. Neither have been adequately used to describe effects on low flow using an index so that estimation of low flow characteristics of sites without discharge measurements has met with limited success. Exceptions are on streams in a region with homogeneous geology, topography, and climate, in which it should be possible to define a range of flow per square mile for a given recurrence interval. -

NOAA Technical Memorandum NMFS-NWFSC-19 Status Review for Klamath Mountains Province Steelhead

NOAA-NWFSC-19 U.S. Dept Commerce/NOAA/NMFS/NWFSC/Publications NOAA-NWFSC Tech Memo-19: Status Review for Klamath Mountains Province Steelhead NOAA Technical Memorandum NMFS-NWFSC-19 Status Review for Klamath Mountains Province Steelhead Peggy J. Busby, Thomas C. Wainwright, and Robin S. Waples National Marine Fisheries Service Northwest Fisheries Science Center Coast Zone and Estuarine Studies Division 2725 Montlake Blvd. E. Seattle WA 98112-2097 December 1994 U.S. DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE Ronald H. Brown, Secretary National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration D. James Baker, Administrator National Marine Fisheries Service Rolland A. Schmitten, Assistant Administrator for Fisheries CONTENTS Summary Acknowledgments http://www.nwfsc.noaa.gov/pubs/tm/tm19/tm19.html (1 of 14) [4/9/2000 9:41:49 AM] NOAA-NWFSC-19 Introduction Scope of Present Status Review Key Questions in ESA Evaluations The "Species" Question Hatchery Fish and Natural Fish Thresholds for Threatened or Endangered Status Summary of Information Relating to the Species Question Environmental Features Ecoregions and Zoogeography Klamath Mountains Geological Province California Current System In-Stream Water Temperature Life History Anadromy-Nonanadromy Steelhead Run-Types Age Structure Half-Pounders Oceanic Migration Patterns Straying History of Hatchery Stocks and Outplantings Steelhead Hatcheries Oregon Hatchery Stocks California Hatchery Stocks Population Genetic Structure Previous Studies New Data Discussion and Conclusions on the Species Question Reproductive Isolation Ecological/Genetic -

KALMIOPSIS Journal of the Native Plant Society of Oregon

KALMIOPSIS Journal of the Native Plant Society of Oregon Kalmiopsis leachiana ISSN 1055-419X Volume 20, 2013 &ôùĄÿĂùñü KALMIOPSIS (irteen years, fourteen issues; that is the measure of how long Journal of the Native Plant Society of Oregon, ©2013 I’ve been editing Kalmiopsis. (is is longer than I’ve lived in any given house or worked for any employer. I attribute this longevity to the lack of deadlines and time clocks and the almost total freedom to create a journal that is a showcase for our state and society. (ose fourteen issues contained 60 articles, 50 book reviews, and 25 tributes to Fellows, for a total of 536 pages. I estimate about 350,000 words, an accumulation that records the stories of Oregon’s botanists, native )ora, and plant communities. No one knows how many hours, but who counts the hours for time spent doing what one enjoys? All in all, this editing gig has been quite an education for me. I can’t think of a more e*ective and enjoyable way to make new friends and learn about Oregon plants and related natural history than to edit the journal of the Native Plant Society of Oregon. Now it is time for me to move on, but +rst I o*er thanks to those before me who started the journal and those who worked with me: the FEJUPSJBMCPBSENFNCFST UIFBVUIPSTXIPTIBSFEUIFJSFYQFSUJTF UIFSFWJFXFST BOEUIF4UBUF#PBSETXIPTVQQPSUFENZXPSL* especially thank those who will follow me to keep this journal &ôùĄÿĂ$JOEZ3PDIÏ 1I% in print, to whom I also o*er my +les of pending manuscripts, UIFTFSWJDFTPGBOFYQFSJFODFEQBHFTFUUFS BSFMJBCMFQSJOUFSBOE &ôùĄÿĂùñü#ÿñĂô mailing service, and the opportunity of a lifetime: editing our +ne journal, Kalmiopsis. -

Characterization of Ecoregions of Idaho

1 0 . C o l u m b i a P l a t e a u 1 3 . C e n t r a l B a s i n a n d R a n g e Ecoregion 10 is an arid grassland and sagebrush steppe that is surrounded by moister, predominantly forested, mountainous ecoregions. It is Ecoregion 13 is internally-drained and composed of north-trending, fault-block ranges and intervening, drier basins. It is vast and includes parts underlain by thick basalt. In the east, where precipitation is greater, deep loess soils have been extensively cultivated for wheat. of Nevada, Utah, California, and Idaho. In Idaho, sagebrush grassland, saltbush–greasewood, mountain brush, and woodland occur; forests are absent unlike in the cooler, wetter, more rugged Ecoregion 19. Grazing is widespread. Cropland is less common than in Ecoregions 12 and 80. Ecoregions of Idaho The unforested hills and plateaus of the Dissected Loess Uplands ecoregion are cut by the canyons of Ecoregion 10l and are disjunct. 10f Pure grasslands dominate lower elevations. Mountain brush grows on higher, moister sites. Grazing and farming have eliminated The arid Shadscale-Dominated Saline Basins ecoregion is nearly flat, internally-drained, and has light-colored alkaline soils that are Ecoregions denote areas of general similarity in ecosystems and in the type, quality, and America into 15 ecological regions. Level II divides the continent into 52 regions Literature Cited: much of the original plant cover. Nevertheless, Ecoregion 10f is not as suited to farming as Ecoregions 10h and 10j because it has thinner soils. -

Irrigation of Wi in Rapes

42 NO VEMBER/DECEMBER 2001 WINEGR OWING ative. The same can be said of a plant's water potential. For example, when more water is Irrigation lost from a leaf via transpiration than moves into the leaf from the vascular tissue, its water potential will become more negative due to a relative increase in its solute concentration. of w i rapes This is important as water in plants and soils moves from regions where water potential is relatively high to regions where water potential is rela- tively low. Such differences in water in potential will result in movement of water from cell to cell within a plant or from regions within the soil profile that Cal Lorry E. WIIIIams y.t portion of the growing season in contain more moisture to those with Department of Viticulture Enology these areas and vineyard water use less. University of California-Qavis, and can be greater than the soil's water One way to measure the water Kearney Agricultural Center reservoir after the winter rainfall, potential of a plant organ in the field supplemental irrigation of vineyards (such as a leaf) is by using a pressure SYNOPSIS: How much irrigation water is may be required at some point dur- chamber. required to grow quality winegrapes ing summer months. The leaf's petiole is cut and the leaf depends upon site, the stage of vine quickly placed into the chamber with growth, row spacing, size of the vine's IRRIGATION MANAGEMENT the cut end of the petiole protruding canopy, and amount of rainfall occur- No matter where grapevines are out of the chamber. -

A Bibliography of Klamath Mountains Geology, California and Oregon

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY A bibliography of Klamath Mountains geology, California and Oregon, listing authors from Aalto to Zucca for the years 1849 to mid-1995 Compiled by William P. Irwin Menlo Park, California Open-File Report 95-558 1995 This report is preliminary and has not been reviewed for conformity with U.S. Geological Survey editorial standards (or with the North American Stratigraphic Code). Any use of trade, product, or firm names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. PREFACE This bibliography of Klamath Mountains geology was begun, although not in a systematic or comprehensive way, when, in 1953, I was assigned the task of preparing a report on the geology and mineral resources of the drainage basins of the Trinity, Klamath, and Eel Rivers in northwestern California. During the following 40 or more years, I maintained an active interest in the Klamath Mountains region and continued to collect bibliographic references to the various reports and maps of Klamath geology that came to my attention. When I retired in 1989 and became a Geologist Emeritus with the Geological Survey, I had a large amount of bibliographic material in my files. Believing that a comprehensive bibliography of a region is a valuable research tool, I have expended substantial effort to make this bibliography of the Klamath Mountains as complete as is reasonably feasible. My aim was to include all published reports and maps that pertain primarily to the Klamath Mountains, as well as all pertinent doctoral and master's theses. -

Volcanic Legacy

United States Department of Agriculture Forest Service Pacifi c Southwest Region VOLCANIC LEGACY March 2012 SCENIC BYWAY ALL AMERICAN ROAD Interpretive Plan For portions through Lassen National Forest, Lassen Volcanic National Park, Klamath Basin National Wildlife Refuge Complex, Tule Lake, Lava Beds National Monument and World War II Valor in the Pacific National Monument 2 Table of Contents INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................................4 Background Information ........................................................................................................................4 Management Opportunities ....................................................................................................................5 Planning Assumptions .............................................................................................................................6 BYWAY GOALS AND OBJECTIVES ......................................................................................................7 Management Goals ..................................................................................................................................7 Management Objectives ..........................................................................................................................7 Visitor Experience Goals ........................................................................................................................7 Visitor -

Ashland Ranger District Rogue River National Forest APPENDICES

'L-JCUMENU A 13.66/2: B 42x/APP./c.4 I V 0) C) oa)4e EN D\ Ashland Ranger District Rogue River National Forest APPENDICES APPENDIX A: KEY ISSUES & KEY QUESTIONS APPENDIX B: FIRE Identification of Specific Vegetation Zones for the Bear Watershed Analysis Area Fire Behavior Fuel Model Key Fuel Model Assignments Chronology of Events APPENDIX C: GEOLOGY, GEOMORPHOLOGY & SOILS Geology and Geomorphology of the Bear Watershed Analysis Area Characteristics of Soil Productivity APPENDIX D: HYDROLOGY What Sort of Debris is Transported Stream Classification Bibliography of Water Quality Studies Map: Drainageways Crossed Map: Dominant Precipitation Patterns APPENDIX E: FISHERIES Historic and Current Miles of Fish Habitat River Mile Index APPENDIX F: AQUATIC AND RIPARIAN HABITAT Habitat Comparison Chart Relative Comparison of Stream Gradients With Coarse Woody Debris Historic and Current Conditions for Aquatic Processes and Functions Maps: Reach Breaks of Neil Creek, West Fork & East Forks of Ashland Creek Table: Processes & Human Influences on Aquatic and Riparian Ecosystems Map: U.S. Fish & Wildlife Surveyed Wetlands Map: Supplemental Water Distribution System Broad Level Delineation of Major Stream Types (Rosgen) Delineative Criteria for Major Stream Types (Rosgen) APPENDIX G: HERITAGE RESOURCES Cultural Uses in the Bear Watershed Analysis Area Chronology of Important Dates APPENDIX A I KEY ISSUES & KEY QUESTIONS Key Questions IMPORTANT TO REMEMBER: These questions drive the analysis for Chapter II: Historic and Current Conditions and Future Trends. CLIMATE Identification of the atmospheric/climate regimes under which the ecosystem of the Bear Watershed Analysis Area have developed is important to this analysis. Attributes to be discussed in this analysis include periods of flood and drought, storm patterns in the winter and summer, occurrence of severe lightning and wind storms, rain on snow events, etc.