<V Design Manual Or Water Wheels

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Generate Your Own Hydropower

Generate Your Own Hydropower Objectives The student will do the following: 1 Build a water wheel. 2 Build a simple galvanometer. 3. Build a simple hydropower generator 4. Detect the electricity generated 5 Demonstrate how water power is converted to electricity. Subjects: Advanced General Science, Physical Science, Physics Time: 1-2 class periods if working in groups of four; 2-3 class periods if working in groups of two Materials: (for each group) compass, 2 alligator clips (optional), small spool magnetic wire (#28 or finer, insulated), 2 cardboard or masonite rectangles (about 5” x7”), glue, (2) 1-inch nails, (2) 3-inch nails, 1-inch bar magnet, (2) 1- 1/2”x4” metal strips cut from tin can, electrical tape, germanium diode (for example, type1N34A), soldering iron (optional), solder (optional), 3x5” wood block, round tinker toy. (8) 3” tinker toy spokes, 8 small paper cups, student sheets (included) Background Information The model hydropower generator made in this activity works much like hydropower plants for generating electricity. When the propeller (water wheel or turbine) spins, the magnet whizzing past the nail head generates a tiny amount of alternating current (AC) in the coil wound around the nail. The small germanium diode connected across the two nail terminals converts the AC into DC (direct current). The galvanometer will indicate that a small current has been produced by the generator. Procedure I The day before the activity is to be done, introduce it to the class A Define and describe a turbine A turbine is a device that has a central drive shaft fitted with curved vanes or blades that cause it to whirl when force is exerted upon it by water, steam, or gas. -

The Impact of Lester Pelton's Water Wheel on the Development Of

VOLUME XXXVIII, NUMBER 3 SUMMER/FALL 2010 A Publication of the Sierra County Historical Society The Impact of Lester Pelton’s Water Wheel On the Development of California Rivals the 49ers! hile hordes of gold-seeking 49ers At the time, steam engines were being W swarmed into the Sierras in search used to provide power to operate the mines of their fortunes, Lester Pelton, a farmer’s but they were expensive to purchase, not son living in Ohio, came to California in easily transported, and consumed enormous W1850 with ambitions amounts of wood resulting that didn’t include gold in forested hillsides mining. He tried making becoming barren in a very money as a fisherman short time. Water wheels in Sacramento before were being tried by some coming to Camptonville mine owners making use after hearing of the gold of the enormous power strike on the north fork available from water in of the Yuba River. Still the mountain regions but not interested in being they were patterned after a miner, Pelton instead water wheels used to power spent his time observing grain mills in the East and the mining operations in Midwest and were not the Camptonville area capable of producing the and noted that both kinds amount of power needed to of mining, placer and operate hoisting equipment hard rock, required large Lester Pelton, whose invention paved the or stamp mills. amounts of power. He way for low-cost hydro-electric power Having never developed realized that hard rock an interest in mining, mining was more difficult to provide because Pelton spent many years doing carpentry power was needed to operate the hoists to and millwrighting, building many homes, a lower men into the mine shafts, bring up schoolhouse, and stamp mills driven by water loaded ore cars, and return the men to the wheels. -

DEPARTMENT of ENGINEERING Course CE 41800 – Hydraulics

DEPARTMENT OF ENGINEERING Course CE 41800 – Hydraulics Engineering Type of Course Required for Civil Engineering Program Catalog Description Sources and distribution of water in urban environment, including surface reservoir requirements, utilization of groundwater, and distribution systems. Analysis of sewer systems and drainage courses for the disposal of both wastewater and storm water. Pumps and lift stations. Urban planning and storm drainage practice. Credits 3 Contact Hours 3 Prerequisite Courses CE 31800 Corequisite Courses None Prerequisites by Fluid Mechanics Topics Textbook Larry Mays, Water Resources Engineering, John Wiley Publishing Company, Current Edition. Course Objectives Students will understand and be able to apply fundamental concepts and techniques of hydraulics and hydrology in the analysis, design, and operation of water resources systems. Course Outcomes Students who successfully complete this course will be able to: 1. Become familiar with different water resources terminology like hydrology, ground water, hydraulics of pipelines and open channel. [a] 2. Understand and be able to use the energy and momentum equations. [a] 3. Analyze flow in closed pipes, and design and selection of pipes including sizes. [a, c, e] 4. Understand pumps classification and be able to develop a system curve used in pump selection. [a, c, e] 5. Design and select pumps (single or multiple) for different hydraulic applications. [a, c, e] Department Syllabus CE – 41800 Page | 1 6. Become familiar with open channel cross sections, hydrostatic pressure distribution and Manning’s law. [a] 7. Determine water surface profiles for gradually varied flow in open channels. [a, e] 8. Familiar with drainage systems and wastewater sources and flow rates. -

Intelligent Hydraulics in New Dimensions. Industrial Hydraulics from Rexroth You Have Our Full Support

Intelligent Hydraulics in New Dimensions. Industrial Hydraulics from Rexroth You Have Our Full Support. Our Dedication is to Your Success With its extensive product range and outstanding application expertise, Rexroth is the technological and market leader in industrial hydraulics. You benefit from the world’s broadest range of standard products, application-adapted products, and special cus- tomized solutions for industrial hydraulics. Teams operating worldwide engineer and deliver complete turnkey systems. Rexroth is the ideal partner for the development of highly efficient plant and machinery—from the initial contact through to commissioning and for the application’s entire life cycle. Extra quality is ensured by Rexroth’s internal quality standards that go beyond the ISO standards and extends our performance specifications consistently to the upper limits. It is precisely in international large-scale projects and research projects that the company’s financial strength forms a firm foun- dation. All over the world, Rexroth can provide you with skilled advice, support, and exceptional service—with its own distribution and service companies in 80 countries. Hydraulics 3 If You Expect Quality, You’re in Good Hands With Rexroth As the world’s leading supplier of industrial hydraulics, Rexroth occupies a prominent position with its parts, systems and specially adapted electronic components. With Rexroth, builders of machines and plant have access to products that consistently set new standards of perfor- mance and quality. Rexroth’s Industrial Hydraulics division located in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania designs and manufactures high-performance, high-productivity hydraulic power units, systems and com- ponents using world-class technologies. Rexroth supports applications in the machine tool and plastics processing machinery, metal forming, civil engineering, power genera- tion, test machinery and simulation, entertainment, presses, automotive, transportation, marine and offshore technology, and wood processing markets. -

Design of Hydraulic Structures 89, Albertson & Kia (Eds) © 1989 Balkema, Rotterdam

P AP-SEi5 PROCEEDINGS OF THE SECOND INTERNATIONAL SYMPOSIUM ON DESIGN OF HYDRAULIC STRUCTURES / FORT COLLINS, COLORADO / 26-29 JUNE 1989 Design of Hydraulic ructures 89 HYDRAULICS BRANCH St OFFICIAL FILE COPY Edited by MAURICE L.ALBERTSON Department of Civil Engineering, Colorado State University, Fort Collins, USA T RAHIM A.KIA Mahab G. Consulting Eng., Tehran, Iran resently: Department of Civil Engineering, Colorado State University, ort Collins, USA OFFPRINT (3— Bureau of Reclamation HYDRAULICS BRANCH RI WHEN BORROWED RETURN PROMPTLY A.A.BALKEMA / ROTTERDAM / BROOKFIELD / 1989 Design of Hydraulic Structures 89, Albertson & Kia (eds) © 1989 Balkema, Rotterdam. ISBN 90 6191 898 7 The role of hydraulic modeling in development of innovative spillway concepts Philip H.Burgi Bureau of Reclamation, Denver, Colo., USA ABSTRACT: The use of hydraulic models to develop and verify the intricate design of waterways to pass flood flows has been closely associated with the development of hydraulic structures over the past 50 years. Since the mid-30's, the Bureau of Reclamation has used laboratory models to develop spillways for large dams such as Hoover, Grand Coulee, Glen Canyon, Yellowtail, and Morrow Point Dams. Documented reports and generalized design criteria have been developed to summarize the results of these investigations. In recent years, Reclamation has developed various innovative spillway concepts which have resulted in cost effective designs for hydraulic structures. This paper will summarize recent laboratory investigations for labyrinth, stepped, and fuse plug spillway concepts as well as retrofit concepts using aerators on spillways and downstream slope protection systems for overtopping low-head embankments. INTRODUCTION Physical model studies are used to investigate the anticipated performance of hydraulic structures. -

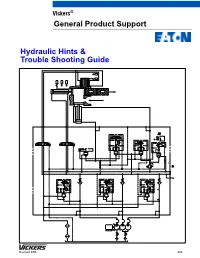

Hydraulic Hints & Trouble Shooting Guide

Vickers® General Product Support Hydraulic Hints & Trouble Shooting Guide Revised 8/96 694 General Hydraulic Hints . 3 Troubleshooting Guide & Maintenance Hints . 4 Chart 1 Excessive Noise . 5 Chart 2 Excessive Heat . 6 Chart 3 Incorrect Flow . 7 Chart 4 Incorrect Pressure . 8 Chart 5 Faulty Operation . 9 Quiet Hydraulics . 10 Contamination Control . 11 Hints on Maintenance of Hydraulic Fluid in the System. 13 Aeration . 14 Leakage Control . 15 Hydraulic Fluid and Temperature Recommendations for Industrial Machinery. 16 Hydraulic Fluid and Temperature Recommendations for Mobile Hydraulic Systems. 19 Oil Viscosity Recommendations . 20 Pump Test Procedure for Evaluation of Antiwear Fluids for Mobile Systems. 21 Oil Flow Velocity in Tubing . 23 Pipe Sizes and Pressure Ratings . 24 Preparation of Pipes, Tubes and Fittings Before Installation in a Hydraulic System. 25 ISO/ANSI Basic Symbols for Fluid Power Equipment and Systems. 26 Conversion Factors . 29 Hydraulic Formulas . 29 2 General Hydraulic Hints Good Assembly Pipes Tubing Do’s And Don’ts Practices Iron and steel pipes were the first kinds Don’t take heavy cuts on thin wall tubing of plumbing used to conduct fluid with a tubing cutter. Use light cuts to Most important – cleanliness. between system components. At prevent deformation of the tube end. If All openings in the reservoir should be present, pipe is the least expensive way the tube end is out or round, a greater to go when assembling a system. possibility of a poor connection exists. sealed after cleaning. Seamless steel pipe is recommended No grinding or welding operations for use in hydraulic systems with the Ream tubing only for removal of burrs. -

The Mechanical Advantage (MA) of the Lever Is Defined As: Effort Arm / Load Arm = D2 / D1

ARIZONA SCIENCE LAB 11/29/17 V40 AZ Science Lab 1 11/29/17 V40 AZ Science Lab 2 Arizona Science Lab: WORKING WITH WATERWHEELS Harnessing the Energy of Water! Institute Of Electrical And Electronic Engineers, Phoenix Section Teacher In Service Program / Engineers In The Classroom (TISP/EIC) “Helping Students Transfer What Is Learned In The Classroom To The World Beyond” Our Sponsors The AZ Science Lab is supported through very generous donations from corporations, non- profit organizations, and individuals, including: 11/29/17 V40 AZ Science Lab 4 Information Sources • For more information on renewable energy, waterwheels, simple machines, and related topics: • www.Wikipedia.com • www.mikids.com/Smachines.htm • www.waterhistory.org • www.youtube.com 11/29/17 V40 AZ Science Lab 5 Norias of Hama, Syria Orontes river ~ 400AD 11/29/17 V40 AZ Science Lab 6 The Science and Engineering of Waterwheels • History – Waterwheels date back to 400 AD! • Energy – Rivers: Kinetic and Potential Energy • Simple Machines – The Power of Leverage • Using Our Science Knowledge: Build a Waterwheel! • Today: Capturing the River – Hydroelectric Power 11/29/17 V40 AZ Science Lab 7 ENERGY What is it? Energy is the ability to do work. Can you name some common forms of energy? 8 AZ Science Lab 11/29/17 V40 What is Energy? Energy is the ability to do work The food we eat contains energy. We use that energy to work and play. Energy can be found in many forms: Chemical energy ElectricalMechanical energy Energy Thermal (heat) energy 11/29/17 V40 AZ Science Lab 9 Mechanical Energy has two forms: Potential Energy (P.E.) – Stored Energy, The Energy of Position (gravitational) Kinetic Energy (K.E.) – Active Energy, The Energy of Motion (motion of waves, electrons, atoms, molecules, and substances) 11/29/17 V40 AZ Science Lab 10 Potential Energy – P.E. -

Hydraulics Manual Glossary G - 3

Glossary G - 1 GLOSSARY OF HIGHWAY-RELATED DRAINAGE TERMS (Reprinted from the 1999 edition of the American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials Model Drainage Manual) G.1 Introduction This Glossary is divided into three parts: · Introduction, · Glossary, and · References. It is not intended that all the terms in this Glossary be rigorously accurate or complete. Realistically, this is impossible. Depending on the circumstance, a particular term may have several meanings; this can never change. The primary purpose of this Glossary is to define the terms found in the Highway Drainage Guidelines and Model Drainage Manual in a manner that makes them easier to interpret and understand. A lesser purpose is to provide a compendium of terms that will be useful for both the novice as well as the more experienced hydraulics engineer. This Glossary may also help those who are unfamiliar with highway drainage design to become more understanding and appreciative of this complex science as well as facilitate communication between the highway hydraulics engineer and others. Where readily available, the source of a definition has been referenced. For clarity or format purposes, cited definitions may have some additional verbiage contained in double brackets [ ]. Conversely, three “dots” (...) are used to indicate where some parts of a cited definition were eliminated. Also, as might be expected, different sources were found to use different hyphenation and terminology practices for the same words. Insignificant changes in this regard were made to some cited references and elsewhere to gain uniformity for the terms contained in this Glossary: as an example, “groundwater” vice “ground-water” or “ground water,” and “cross section area” vice “cross-sectional area.” Cited definitions were taken primarily from two sources: W.B. -

A New, More Efficient Waterwheel Design for Very-Low-Head Hydropower Schemes

A new, more efficient waterwheel design for very-low-head hydropower schemes David Ross Carruthers Penelope Carruthers Rebecca Wade This is the peer reviewed version of the following article: Carruthers, D.R., Carruthers, P. and Wade, R. 2018. A new, more efficient waterwheel design for very-low-head hydropower schemes. Proceedings of the Institution of Civil Engineers: Civil Engineering. which has been published in final form at doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1680/jcien.17.00051 Journal: Proceedings of the Institution of Civil Engineers – Civil Engineering Research Article - Paper 1700051 Received 19/12/2017 Accepted 21/02/2018 Title: A new, more efficient waterwheel design for very-low-head hydropower schemes Authors: 1. David Ross Carruthers LL.M. Eur., MBA, LLB, MEng, BSc, FICE Engineering Manager, Carruthers Renewables Limited, Perth, UK (corresponding author: [email protected]) (Orcid: 0000-0001-9014-3715) 2. Penelope Carruthers BSc, HND Chief Executive Officer, Carruthers Renewables Limited, Perth, UK (Orcid: 0000-0001-5954-3841) 3. Rebecca Wade MA, PhD Senior Lecturer, Abertay University, Dundee, UK (Orcid: 0000-0002-8419-0651) Abstract: Very-low-head hydropower constitutes a large untapped renewable energy source, estimated at 1 GW in the UK alone. A new type of low-impact waterwheel has been developed and tested at Abertay University in Scotland to improve the economic viability of such schemes. For example, on a 2·5 m high weir in the UK with 5 m3/s mean flow, one waterwheel could produce an annual investment return of 7·5% for over 100 years. This paper describes the evolution of the design and reports on scale-model tests. -

Egyptian and Greek Water Cultures and Hydro-Technologies in Ancient Times

sustainability Review Egyptian and Greek Water Cultures and Hydro-Technologies in Ancient Times Abdelkader T. Ahmed 1,2,* , Fatma El Gohary 3, Vasileios A. Tzanakakis 4 and Andreas N. Angelakis 5,6 1 Civil Engineering Department, Faculty of Engineering, Aswan University, Aswan 81542, Egypt 2 Civil Engineering Department, Faculty of Engineering, Islamic University, Madinah 42351, Saudi Arabia 3 Water Pollution Research Department, National Research Centre, Cairo 12622, Egypt; [email protected] 4 Department of Agriculture, School of Agricultural Science, Hellenic Mediterranean University, Iraklion, 71410 Crete, Greece; [email protected] 5 HAO-Demeter, Agricultural Research Institution of Crete, 71300 Iraklion, Greece; [email protected] 6 Union of Water Supply and Sewerage Enterprises, 41222 Larissa, Greece * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 2 October 2020; Accepted: 19 November 2020; Published: 23 November 2020 Abstract: Egyptian and Greek ancient civilizations prevailed in eastern Mediterranean since prehistoric times. The Egyptian civilization is thought to have been begun in about 3150 BC until 31 BC. For the ancient Greek civilization, it started in the period of Minoan (ca. 3200 BC) up to the ending of the Hellenistic era. There are various parallels and dissimilarities between both civilizations. They co-existed during a certain timeframe (from ca. 2000 to ca. 146 BC); however, they were in two different geographic areas. Both civilizations were massive traders, subsequently, they deeply influenced the regional civilizations which have developed in that region. Various scientific and technological principles were established by both civilizations through their long histories. Water management was one of these major technologies. Accordingly, they have significantly influenced the ancient world’s hydro-technologies. -

Basic Hydraulics and Components

Pub.ES-100-2 BASIC HYDRAULICSANDCOMPONENTS BASIC HYDRAULICS AND COMPONENTS OIL HYDRAULIC EQUIPMENT ■ Overseas Business Department Hamamatsucho Seiwa Bldg., 4-8, Shiba-Daimon 1-Chome, Minato-ku, Tokyo 105-0012 JAPAN TEL. +81-3-3432-2110 FAX. +81-3-3436-2344 Preface This book provides an introduction to hydraulics for those unfamiliar with hydraulic systems and components, such as new users, novice salespeople, and fresh recruits of hydraulics suppliers. To assist those people to learn hydraulics, this book offers the explanations in a simple way with illustrations, focusing on actual hydraulic applications. The first edition of the book was issued in 1986, and the last edition (Pub. JS-100-1A) was revised in 1995. In the ten years that have passed since then, this book has become partly out-of-date. As hydraulic technologies have advanced in recent years, SI units have become standard in the industrial world, and electro-hydraulic control systems and mechatronics equipment are commercially available. Considering these current circumstances, this book has been wholly revised to include SI units, modify descriptions, and change examples of hydraulic equipment. Conventional hydraulic devices are, however, still used in many hydraulic drive applications and are valuable in providing basic knowledge of hydraulics. Therefore, this edition follows the preceding edition in its general outline and key text. This book principally refers hydraulic products of Yuken Kogyo Co., Ltd. as example, but does mention some products of other companies, with their consent, for reference to equipment that should be understood. We acknowledge courtesy from those companies who have given us support for this textbook. -

Waterwheel Work Lesson Plan

INL’s K-12 STEM Program works to inspire Idaho’s future STEM workforce, impact students, OUR MISSION teachers and families by integrating best practices in STEM education, and empower employees to become STEM mentors to transform K-12 STEM into a driver for innovation. WATERWHEEL WORK OVERVIEW With energy consumption increasing, alternate energy sources are in greater demand. The U.S. Department of Energy’s (DOE) Water Power Technologies Office (WPTO) is leading research to modernize hydropower to meet current and future electrical grid needs. Idaho National Laboratory (INL) is part of this research. Instead of building dams with huge reservoirs of water, researchers are trying to harness the water power of rivers. This is called “run of the river” (ROR). The researchers at INL are collaborating with Idaho Falls Power. There are currently four “run of the river” power plants on the Snake River. Instead of using a reservoir, a portion of a river is channeled into a hydropower plant. Because the amount of water in a river can vary, it makes it hard to rely on how much water can be used to generate electricity. INL is leading the WPTO’s Integrated project. This is a research effort to provide grid balancing through integration with energy storage systems so that a ROR hydropower plant can control the amount of power it puts on the grid, filling the same balancing role as conventional hydropower. In this activity students will create an experimental water wheel (precursor to the turbines used today in hydroelectric power plants) from a plastic water bottle.