Overview of the Kukutaaruhe Gully Restoration Initiative

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

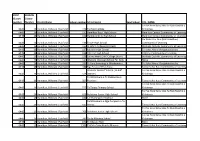

FIRST Cluster Number EDUMIS Cluster Number Cluster Name

FIRST EDUMIS Cluster Cluster number Number Cluster Name School number School name Lead School COL_NAME Te Pae Here Kahui Ako Te Raki Rawhiti o 6445 16 Hamilton /Hillcrest /Fairfield 129 Fairfield College Kirikiriroa 6445 16 Hamilton /Hillcrest /Fairfield 131 Hamilton Boys' High School Hamilton Central Community of Learning 6445 16 Hamilton /Hillcrest /Fairfield 132 Hamilton Girls' High School Hamilton Central Community of Learning He Waka Eke Noa (NW Hamilton) 6445 16 Hamilton /Hillcrest /Fairfield 135 Fraser High School Community of Learning 6445 16 Hamilton /Hillcrest /Fairfield 136 St John's College (Hillcrest) Waikato Catholic Community of Learning 6445 16 Hamilton /Hillcrest /Fairfield 137 Melville High School Te Kahui Ako o Mangakatukutuku 6445 16 Hamilton /Hillcrest /Fairfield 138 Hillcrest High School Hillcrest Community of Learning 6445 16 Hamilton /Hillcrest /Fairfield 139 Sacred Heart Girls' College (Ham) Waikato Catholic Community of Learning 6445 16 Hamilton /Hillcrest /Fairfield 140 Waikato Diocesan School For Girls None 6445 16 Hamilton /Hillcrest /Fairfield 282 Te Kura Amorangi o Whakawatea Te Kahui Ako o Mangakatukutuku 6445 16 Hamilton /Hillcrest /Fairfield 488 Nga Taiatea Wharekura Tainui Kahui Kura Community of Learning Waikato Waldorf School ( Rudolf Te Pae Here Kahui Ako Te Raki Rawhiti o 6445 16 Hamilton /Hillcrest /Fairfield 539 Steiner) Kirikiriroa Te Wharekura o Te Kaokaoroa o 6445 16 Hamilton /Hillcrest /Fairfield 567 Patetere Tainui Kahui Kura Community of Learning Te Pae Here Kahui Ako Te Raki Rawhiti o 6445 -

Schools Advisors Territories

SCHOOLS ADVISORS TERRITORIES Gaynor Matthews Northland Gaynor Matthews Auckland Gaynor Matthews Coromandel Gaynor Matthews Waikato Angela Spice-Ridley Waikato Angela Spice-Ridley Bay of Plenty Angela Spice-Ridley Gisborne Angela Spice-Ridley Central Plateau Angela Spice-Ridley Taranaki Angela Spice-Ridley Hawke’s Bay Angela Spice-Ridley Wanganui, Manawatu, Horowhenua Sonia Tiatia Manawatu, Horowhenua Sonia Tiatia Welington, Kapiti, Wairarapa Sonia Tiatia Nelson / Marlborough Sonia Tiatia West Coast Sonia Tiatia Canterbury / Northern and Southern Sonia Tiatia Otago Sonia Tiatia Southland SCHOOLS ADVISORS TERRITORIES Gaynor Matthews NORTHLAND REGION AUCKLAND REGION AUCKLAND REGION CONTINUED Bay of Islands College Albany Senior High School St Mary’s College Bream Bay College Alfriston College St Pauls College Broadwood Area School Aorere College St Peters College Dargaville High School Auckland Girls’ Grammar Takapuna College Excellere College Auckland Seven Day Adventist Tamaki College Huanui College Avondale College Tangaroa College Kaitaia College Baradene College TKKM o Hoani Waititi Kamo High School Birkenhead College Tuakau College Kerikeri High School Botany Downs Secondary School Waiheke High School Mahurangi College Dilworth School Waitakere College Northland College Diocesan School for Girls Waiuku College Okaihau College Edgewater College Wentworth College Opononi Area School Epsom Girls’ Grammar Wesley College Otamatea High School Glendowie College Western Springs College Pompallier College Glenfield College Westlake Boys’ High -

Zoned Schools for This Property Early Childhood Educa on Primary

Street Address: 6 Dalethorpe Avenue, Fairfield, Hamilton Zoned Schools for this Property Primary / Intermediate Schools FAIRFIELD INTERMEDIATE 1.3 km WOODSTOCK SCHOOL 0.2 km Secondary Schools No results found Early Childhood Educaon Hamilton Home Based Childcare-Network 2 19 A O'Neill Street Distance: 0.1 km Claudelands 20 Hours Free: Yes Hamilton Type: Homebased Network Ph. 07-8551899 Authority: Community Based Jack and Jill Educare 29 Gallagher Drive Distance: 0.4 km Melville 20 Hours Free: Yes Hamilton Type: Educaon & Care Service Ph. 07-8434420 Authority: Privately Owned Scallywaggs SPROUTS In-Home Childcare Hawke's Bay 4 2 Maadi Road Distance: 0.4 km Onekawa 20 Hours Free: Yes Napier Type: Homebased Network Ph. 06-8422015 Authority: Privately Owned Scallywaggs SPROUTS In-Home Childcare Hawke's Bay 5 2 Maadi Road Distance: 0.4 km Onekawa 20 Hours Free: Yes Napier Type: Homebased Network Ph. 06-8422015 Authority: Privately Owned Sprouts In-Home Childcare Manawatu 8 28 Shamrock Street Distance: 0.4 km Takaro 20 Hours Free: Yes Palmerston North Type: Homebased Network Ph. 06-3535303 Authority: Privately Owned Primary / Intermediate Schools FAIRFIELD INTERMEDIATE Clarkin Road Distance: 1.3 km Fairfield Decile: 5 Hamilton Age Range: Intermediate Ph. 07 855 9718 Authority: State Gender: Co-Educaonal School Roll: 788 Zoning: In Zone FAIRFIELD PRIMARY SCHOOL 260 Clarkin Road Distance: 1.1 km Fairfield Decile: 1 Hamilton Age Range: Contribung Ph. 07 855 6284 Authority: State Gender: Co-Educaonal School Roll: 312 Zoning: Out of Zone ST JOSEPH'S CATHOLIC SCHOOL (FAIRFIELD) 88 Clarkin Road Distance: 0.3 km Hamilton Decile: 7 Ph. -

Schools and Schools Zones Relating to a Property

Schools and schools zones relating to a property The School Report provides detailed information on school zones, from Early Childhood Education through to Tertiary Institutions. Street Address: 27 Fuchsia Avenue, Pukete, Hamilton Zoned Schools for this Property Primary / Intermediate Schools PUKETE SCHOOL 0.5 km Secondary Schools HAMILTON'S FRASER HIGH SCHOOL 4.9 km Early Childhood Education Ashurst Park Playcentre 61 Ashurst Avenue Distance: 0.3 km Pukete 20 Hours Free: No Hamilton Type: Playcentre Ph. 07-8471739 Authority: Community Based Bright Babes - Preschool 1-3 Cullimore Street Distance: 0.6 km Pukete 20 Hours Free: Yes Hamilton Type: Education & Care Service Ph. 07-8496780 Authority: Privately Owned Lollipops Educare Te Rapa 44 Church Road Distance: 0.7 km Te Rapa 20 Hours Free: Yes Hamilton Type: Education & Care Service Ph. 07-8490952 Authority: Privately Owned Pukete Kindergarten 13 Cullimore Street Distance: 0.6 km Pukete 20 Hours Free: Yes Hamilton Type: Free Kindergarten Ph. 07-8493718 Authority: Community Based Tokoroa Childcare Centre 50 Maraetai Road Distance: 0.6 km Tokoroa 20 Hours Free: Yes Ph. 07-8868605 Type: Education & Care Service Authority: Community Based Rupert Bain – Harcourts (Hamilton) 13 Feb 2017, page 1 of 4 Primary / Intermediate Schools ENDEAVOUR SCHOOL Endeavour Avenue, Flagstaff Hamilton Distance: 1.4 km Flagstaff Decile: 10 Hamilton Age Range: Contributing Ph. 07 855 5257 Authority: State Gender: Co-Educational School Roll: Zoning: Out of Zone PUKETE SCHOOL Pukete Road Distance: 0.5 km Pukete Decile: 5 Hamilton Age Range: Contributing Ph. 07 849 4352 Authority: State Gender: Co-Educational School Roll: 430 Zoning: In Zone ST PETER CHANEL CATHOLIC SCH (TE RAPA) 5 Vardon Street Distance: 2.9 km Te Rapa Decile: 7 Hamilton Age Range: Full Primary Ph. -

Schools and Schools Zones Relating to a Property

Schools and schools zones relating to a property The School Report provides detailed information on school zones, from Early Childhood Education through to Tertiary Institutions. Street Address: 68 Fairview Street, Fairview Downs, Hamilton Zoned Schools for this Property Primary / Intermediate Schools FAIRFIELD INTERMEDIATE 1.2 km PEACHGROVE INTERMEDIATE 2.7 km Secondary Schools No results found Early Childhood Education ABC Peachgrove Road Hamilton 205 Peachgrove Road Distance: 1.6 km Hamilton Central 20 Hours Free: Yes Hamilton Type: Education & Care Service Ph. 07-8555411 Authority: Privately Owned Fairfield Kindergarten 29 Kenney Crescent Distance: 1.2 km Fairfield 20 Hours Free: Yes Hamilton Type: Free Kindergarten Ph. 07-8556300 Authority: Community Based Insoll Kindergarten 65 Halberg Crescent Distance: 0.5 km Hamilton Central 20 Hours Free: Yes Hamilton Type: Free Kindergarten Ph. 07-8555740 Authority: Community Based Te Whanau Putahi 37 Oxford Street Distance: 1.5 km Fairfield-Hamilton 20 Hours Free: Yes Hamilton Type: Education & Care Service Ph. 07-8550419 Authority: Community Based Whakapiripiri Ki Te Iwi Fifth Avenue Distance: 1.1 km Fairfield-Hamilton 20 Hours Free: No Hamilton Type: Te Kohanga Reo Ph. 07-8553886 Authority: Community Based Rupert Bain – Harcourts (Hamilton) 14 Oct 2016, page 1 of 4 Primary / Intermediate Schools FAIRFIELD INTERMEDIATE Clarkin Road Distance: 1.2 km Fairfield Decile: 5 Hamilton Age Range: Intermediate Ph. 07 855 9718 Authority: State Gender: Co-Educational School Roll: 788 Zoning: In Zone FAIRFIELD PRIMARY SCHOOL 260 Clarkin Road Distance: 1.4 km Fairfield Decile: 1 Hamilton Age Range: Contributing Ph. 07 855 6284 Authority: State Gender: Co-Educational School Roll: 312 Zoning: No Zone INSOLL AVENUE SCHOOL 95 Insoll Avenue Distance: 0.3 km Fairfield Decile: 1 Hamilton Age Range: Contributing Ph. -

2021 NZ Secondary School Open Water Swimming Championships Blue Lake, Rotorua Saturday 20 March 2021 Entry List

2021 NZ Secondary School Open Water Swimming Championships Blue Lake, Rotorua Saturday 20 March 2021 Entry List First Name Surname Date of Birth Gender School Race Sian Bester 29/04/2004 Female Albany Senior High School 3.5km Aidan Bollee 18/09/2007 Male Aquinas College 3.5km Kate Dekker 10/02/2006 Female Aquinas College 3.5km Nathan Holmberg 30/03/2007 Male Aquinas College 3.5km Grace Rickit 12/12/2007 Female Aquinas College 3.5km Harry Dufaur 12/12/2003 Male Auckland Grammar School 3.5km Jayden Collins 14/12/2005 Male Avondale College 3.5km Alex Dunkley 8/04/2005 Male Avondale College 3.5km Sam Brown 17/12/2005 Male Awatapu College 3.5km Venetia Hickey 21/01/2008 Female Baradene College of the Sacred Heart 3.5km Lilliana Guy 26/08/2005 Female Bethlehem College 3.5km Paris Mcconnell 16/10/2005 Female Bethlehem College 3.5km Mae-Ying Reynolds 20/11/2007 Female Botany Downs Secondary College 3.5km Abby Wright 30/10/2003 Female Bream Bay College 3.5km Charlotte Watt 4/08/2005 Female Cambridge High School 3.5km Jamie Joblin 28/11/2003 Male Campion College 3.5km Ben Smith 2/04/2005 Male Christchurch Boys High School 3.5km Keira Maccalman 21/06/2005 Female Christchurch Girls High School 3.5km Holly Smith 2/08/2006 Female Christchurch Girls High School 3.5km Peta Clark 16/03/2005 Female Diocesan School for Girls 3.5km Olivia Bates 7/02/2008 Female Epsom Girls Grammar School 3.5km Hannah Henson 4/02/2006 Female Epsom Girls Grammar School 3.5km Emily Pilbrow 28/01/2004 Female Epsom Girls Grammar School 3.5km Daniel Callebaut 25/05/2006 Male Francis -

PLACE SCHOOL FIRST LAST NAME TIME 1 St Peter's School

JUNIOR GIRLS PLACE SCHOOL FIRST LAST NAME TIME Top 3 Man Score 1 St Peter's School (Cambridge) Charli MILLER 11 1st Waikato Diocesan School For Girls 26 2 Otumoetai College Olivia CUMMINGS 11.31 2nd St Peter's School (Cambridge) 64 3 Otumoetai College Antonia BALLANTYNE 11.54 3rd Cambridge High School 77 4 Tauhara College Case MASTNY-JENSEN 12.07 5 Te Kuiti High School Samantha CORBETT 12.08 Top 6 Man Score 6 Waikato Diocesan School For Girls Ele BARTON 12.14 1st Waikato Diocesan School For Girls 100 7 Trident High School Isobel WOTTON 12.18 2nd Hamilton Girls High 202 8 Rototuna Junior High Erin FOBBESTER 12.23 3rd St Peter's School (Cambridge) 214 9 Waikato Diocesan School For Girls Lucy FARRELL 12.34 10 Sacred Heart Girls' College (Hamilton) Krystie SOLOMON 12.47 11 Waikato Diocesan School For Girls Emma BARTON 12.52 12 Cambridge High School Amelie DIKMANS 12.53 13 Hamilton Girls High School Maria SARTIN 13.01 14 Waikato Diocesan School For Girls Ella HARSANT 13.02 15 Tauranga Girls' College Ellie RICHARDSON 13.03 16 Hauraki Plains College Anna MCCOWATT 13.05 17 Mt Maunganui College Hope PRESTON 13.06 18 Sacred Heart Girls' College (Hamilton) Amelia HUNT 13.07 19 Rototuna Junior High Abbie WATSON 13.12 20 John Paul College Madison Mitchell 13.16 21 St Peter's School (Cambridge) Sophie WADDELL 13.21.24 22 Morrinsville College Aisha MORRIS-WALTON 13.21.51 23 Waikato Diocesan School For Girls Sacha MCLEOD 13.22 24 Aquinas College Emily DAVIES 13.23 25 Te Awamutu College Ruby KIRWIN 13.27.04 26 Taupo Nui-a-tia College Olivia PITIROI-GOWLING -

Education Region (Total Allocation) Cluster

Additional Contribution to Base LSC FTTE Whole Remaining FTTE Total LSC for Education Region Resource (Travel Cluster Name School Name School Roll cluster FTTE based generated by FTTE by to be allocated the Cluster (Total Allocation) Time/Rural etc) on school roll cluster (A) school across cluster (A + B) (B) Colville School 37 0.07 Coroglen School 31 0.06 Coromandel Area School 197 0.39 Hikuai School 54 0.11 Coromandel Community of Learning Opoutere School 96 0.19 2 1 1 3 Tairua School 138 0.28 Te Rerenga School 71 0.14 Whangamata Area School 492 0.98 1 Whenuakite School 123 0.25 Hauraki Plains College 782 1.56 1 Kaiaua School 17 0.03 Kaihere School 37 0.07 Kerepehi School 65 0.13 Kopuarahi School 17 0.03 Mangatangi School 104 0.21 Hauraki Community of Learning 4 3 0 4 Mangatawhiri School 187 0.37 Maramarua School 57 0.11 Ngatea School 336 0.67 Orere School 28 0.06 Turua Primary School 95 0.19 Waitakaruru School 73 0.15 Aberdeen School 637 1.27 1 Crawshaw School 308 0.62 Forest Lake School 348 0.70 Frankton School 656 1.31 1 Fraser High School 1,460 2.92 2 Waikato Horotiu School 239 0.48 He Waka Eke Noa (NW Hamilton) Community of Learning Maeroa Intermediate 781 1.56 12 1 6 0 12 Nawton School 485 0.97 1 Rhode Street School 210 0.42 Te Kowhai School 280 0.56 Vardon School 310 0.62 Whatawhata School 273 0.55 Whitiora School 235 0.47 Huntly College 212 0.42 Huntly School (Waikato) 207 0.41 Huntly District Community of Learning 1 1 0 1 Ruawaro Combined School 58 0.12 Taupiri School 73 0.15 Kio Kio School 111 0.22 Maihiihi School 96 0.19 -

Charli MILLER 11 1St Waikato Diocesan School for Girls 26 2 Ot

JUNIOR GIRLS PLACE SCHOOL FIRST LAST NAME TIME Top 3 Man Score 1 St Peter's School (Cambridge) Charli MILLER 11 1st Waikato Diocesan School For Girls 26 2 Otumoetai College Olivia CUMMINGS 11.31 2nd St Peter's School (Cambridge) 64 3 Otumoetai College Antonia BALLANTYNE 11.54 3rd Cambridge High School 77 4 Tauhara College Case MASTNY-JENSEN 12.07 5 Te Kuiti High School Samantha CORBETT 12.08 Top 6 Man Score 6 Waikato Diocesan School For Girls Ele BARTON 12.14 1st Waikato Diocesan School For Girls 100 7 Trident High School Isobel WOTTON 12.18 2nd Hamilton Girls High 202 8 Rototuna Junior High Erin FOBBESTER 12.23 3rd St Peter's School (Cambridge) 214 9 Waikato Diocesan School For Girls Lucy FARRELL 12.34 10 Sacred Heart Girls' College (Hamilton) Krystie SOLOMON 12.47 11 Waikato Diocesan School For Girls Emma BARTON 12.52 12 Cambridge High School Amelie DIKMANS 12.53 13 Hamilton Girls High School Maria SARTIN 13.01 14 Waikato Diocesan School For Girls Ella HARSANT 13.02 15 Tauranga Girls' College Ellie RICHARDSON 13.03 16 Hauraki Plains College Anna MCCOWATT 13.05 17 Mt Maunganui College Hope PRESTON 13.06 18 Sacred Heart Girls' College (Hamilton) Amelia HUNT 13.07 19 Rototuna Junior High Abbie WATSON 13.12 20 John Paul College Madison Mitchell 13.16 21 St Peter's School (Cambridge) Sophie WADDELL 13.21.24 22 Morrinsville College Aisha MORRIS-WALTON 13.21.51 23 Waikato Diocesan School For Girls Sacha MCLEOD 13.22 24 Aquinas College Emily DAVIES 13.23 25 Te Awamutu College Ruby KIRWIN 13.27.04 26 Taupo Nui-a-tia College Olivia PITIROI-GOWLING -

Impact Report 2020-2021

Impact Report 2020-2021 Chairperson’s Report The past year has presented the world with so many unexpected challenges, with Covid at the centre of many of these challenges. Our POET schools, like us all, have been forced We love your “can do“ attitude! to operate in an environment of fear, constantly changing rules and guidelines, sudden adaptation This year has definitely not just been about of plans, social distancing, isolation and a new way putting out Covid fires. In October last year of doing things including teaching and learning we farewelled Donald who left us to follow his 266 guests in September, raising funds to remotely online. passion for the environment, taking up a role as support our programmes and inspiring us all to a community and iwi planner for DOC. Thank get out there and active. All of us at POET are proud of the way our schools you Donald for all your hard work, your great have responded. They very quickly recognised ideas and your commitment to our youth. A highlight for POET this year has been our that now more than ever getting out in nature with involvement with the Te Toki Voyaging Trust their peers is a vital tool for keeping our young We appointed Sophie Milne from a strong field at Kawhia. Several of our schools have been people healthy. This year POET doubled the of 50 applicants to replace Donald. Sophie has lucky enough to experience time on the waka number of days of support we have provided a strong academic and teaching background at Kawhia, learning traditional sailing and our schools in terms of programme to go with her experience in and passion for navigation skills and developing team work. -

Schools and Schools Zones Relating to a Property

Schools and schools zones relating to a property The School Report provides detailed information on school zones, from Early Childhood Education through to Tertiary Institutions. Street Address: 44b Charlemont Street, Whitiora, Hamilton Zoned Schools for this Property Primary / Intermediate Schools MAEROA INTERMEDIATE 0.6 km MARIAN CATHOLIC SCHOOL (HAMILTON) 3.1 km Secondary Schools HAMILTON'S FRASER HIGH SCHOOL 2.1 km Early Childhood Education Central Baptist Childcare 33 Charlemont Street Distance: Hamilton Central 20 Hours Free: Yes Hamilton Type: Education & Care Service Ph. 07-8380273 Authority: Community Based Hamilton Home Based Childcare-Network 2 19 A O'Neill Street Distance: 0.8 km Claudelands 20 Hours Free: Yes Hamilton Type: Homebased Network Ph. 07-8551899 Authority: Community Based PORSE Hamilton S1 146 Ulster St Distance: 0.6 km Whitiora 20 Hours Free: Yes Hamilton Type: Homebased Network Ph. 07-8532666 Authority: Privately Owned Thames Early Childhood Education Centre 100 Haven Street Distance: 0.9 km Thames 20 Hours Free: Yes Ph. 07-8687028 Type: Education & Care Service Authority: Community Based Whitiora Kindergarten 45 Abbotsford Street Distance: 0.6 km Whitiora 20 Hours Free: Yes Hamilton Type: Free Kindergarten Ph. 07-8381614 Authority: Community Based Rupert Bain – Harcourts (Hamilton) 23 May 2018, page 1 of 4 Primary / Intermediate Schools FOREST LAKE SCHOOL Storey Avenue Distance: 1.0 km Hamilton Decile: 4 Ph. 07 849 2256 Age Range: Contributing Authority: State Gender: Co-Educational School Roll: 190 Zoning: Out of Zone MAEROA INTERMEDIATE Churchill Avenue Distance: 0.6 km Hamilton Decile: 3 Ph. 07 847 5014 Age Range: Intermediate Authority: State Gender: Co-Educational School Roll: 621 Zoning: In Zone MARIAN CATHOLIC SCHOOL (HAMILTON) Cnr Clyde & Firth Streets Distance: 3.1 km Hamilton Decile: 7 Ph. -

Schools and Schools Zones Relating to a Property

Schools and schools zones relating to a property The School Report provides detailed information on school zones, from Early Childhood Education through to Tertiary Institutions. Street Address: 109 Maeroa Road, Maeroa, Hamilton Zoned Schools for this Property Primary / Intermediate Schools FOREST LAKE SCHOOL 0.5 km MAEROA INTERMEDIATE 0.4 km Secondary Schools HAMILTON'S FRASER HIGH SCHOOL 1.7 km Early Childhood Education Central Baptist Childcare 33 Charlemont Street Distance: 0.5 km Hamilton Central 20 Hours Free: Yes Hamilton Type: Education & Care Service Ph. 07-8380273 Authority: Community Based Jamieson Kindergarten 70 Storey Avenue Distance: 0.6 km Forest Lake 20 Hours Free: Yes Hamilton Type: Free Kindergarten Ph. 07-8492684 Authority: Community Based Thames Early Childhood Education Centre 100 Haven Street Distance: 0.6 km Thames 20 Hours Free: Yes Ph. 07-8687028 Type: Education & Care Service Authority: Community Based The Montessori Foundation 1 163 Rimu Street Distance: 0.8 km Forest Lake 20 Hours Free: No Hamilton Type: Education & Care Service Ph. 07-8472172 Authority: Community Based Waterworld Educare Garnett Avenue Distance: 0.5 km Te Rapa 20 Hours Free: No Hamilton Type: Education & Care Service Ph. 07-9585864 Authority: Community Based Rupert Bain – Harcourts (Hamilton) 01 Mar 2018, page 1 of 4 Primary / Intermediate Schools FOREST LAKE SCHOOL Storey Avenue Distance: 0.5 km Hamilton Decile: 4 Ph. 07 849 2256 Age Range: Contributing Authority: State Gender: Co-Educational School Roll: 190 Zoning: In Zone MAEROA INTERMEDIATE Churchill Avenue Distance: 0.4 km Hamilton Decile: 3 Ph. 07 847 5014 Age Range: Intermediate Authority: State Gender: Co-Educational School Roll: 621 Zoning: In Zone ST PETER CHANEL CATHOLIC SCH (TE RAPA) 5 Vardon Street Distance: 1.2 km Te Rapa Decile: 7 Hamilton Age Range: Full Primary Ph.