Se7en: Medieval Justice, Modern Justice

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Humility, Justice, Goodness

SANTA MARGARITA CATHOLIC HIGH SCHOOL strives to bring the nurturing charism of Caritas Christi – the love of Christ – to our community of faith and learning. In the 17th century, Jesus revealed a vision of His Sacred Heart to St. Margaret Mary Alacoque, the patroness of our school. It is the heart of Jesus that impels us to live Caritas Christi. By embodying Gospel values we can be the heart of Christ in the world today. OUR CORE PRINCIPLES To live CARITAS CHRISTI is to be a person of: COMPASSION, who ACTS and SPEAKS with concern for others. “Do nothing from selfishness; rather, humbly regard others as more important than yourselves.” - Philippians 2:3 • Affirm the inherent value and dignity of each person • Be present to another’s needs • Forgive another, as you would want to be forgiven HUMILITY, who UNDERSTANDS themselves in relationship to God. “The Son of Man came not to be served but to serve.” – Mark 1:45 • Express gratitude to God for life’s many gifts • Engage life as a “We” rather than a “Me” person • Use one’s gifts in service to others JUSTIC E, who RESPECTS and ADVOCATES for the dignity of ALL PEOPLE and CREATION. “Blessed are those who do what is right, whose deeds are always just.” – Psalm 106:3 • Give generously without expecting something in return • Speak and act truefully in all circumstances • Seek and promote the well-being of others GOODNESS, who reflects the image of God in THOUGHT, WORD and ACTION. “You have been told what is good, and what the Lord requires of you: Only to do justice and to love goodness, and to walk humbly with your God.” – Micah 6:8 • Develop and demonstrate moral character that reflects the virtues of Christ • Encourage one another and build one another up • Accompany each other on life’s spiritual journey . -

Spark Festival Uk Green Film Festival

15 BOX OFFICE — 0116 242 2800 phoenix.org.uk MAY CINEMA / ART / CAFÉ BAR PHOENIX 8 – 14 May NEW FILMS — FAR FROM THE MADDING CROWD A GIRL WALKS HOME THIS MONTH — ALONE AT NIGHT SPARK FESTIVAL Creative fun for all the family STONES FOR THE RAMPART UK GREEN FILM FESTIVAL FORCE MAJEURE We join cinemas nationwide to celebrate environmental films SAMBA MAY AT A GLANCE FAR FROM THE MADDING CROWD P4 <MultipleINTERSECTING LINKS > <MULTIPLEINTERSECTING LINKS> Box Office242 2800 0116 — GOOD KILL P4 CHILD 44 P6 FORCE MAJEURE P5 Book Online — www.phoenix.org.uk BEVERLEY + MAKING OF DOC P5 <MultipleINTERSECTING LINKS > <MULTIPLEINTERSECTING LINKS> JOHN WICK P6 STONES FOR THE RAMPART P5 PHOENIX P6 THE VOICES P7 <MultipleINTERSECTING LINKS > <MULTIPLEINTERSECTING LINKS> THE WATER DIVINER P7 THE FALLING P10 A ROYAL NIGHT OUT P7 WOMAN IN GOLD P10 8 1/2 P10 COMING IN JUNE CLOUDS OF SILS MARIA MR HOLMES TIMBUKTU 2 – 3 DISCOVER FILM DISCOVER PHOENIX FIND WELCOME It’s Spark Festival time again! Leicester is home to the biggest children’s arts festival in the country, and at Phoenix our programme is jam–packed with digital fun for all ages. Experiment with new technologies in a short workshop; catch a family film; or create your own ‘light art’ in our Cube Gallery with Water Light Graffiti, an amazing wall embedded with thousands of LEDs that light up when you paint on it with water. A huge thank you to everyone who filled in our annual customer survey last month: we got over 950 responses. We’re currently looking through all your comments to see how we can make things better for you, and shape Phoenix’s future as we continue to adapt to pressures on public funding. -

Justice and Humility in Technology Design

2006-85: JUSTICE AND HUMILITY IN TECHNOLOGY DESIGN Steven VanderLeest, Calvin College Steven H. VanderLeest is a Professor of Engineering at Calvin College. He has an M.S.E.E. from Michigan Tech. U. (1992) and Ph.D. from the U of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign (1995). He received a “Who’s Who Among America’s Teachers” Award in 2004 and 2005 and was director of a FIPSE grant “Building IT Fluency into a Liberal Arts Core Curriculum.” His research includes responsible technology and software partitioned OS. Page 11.851.1 Page © American Society for Engineering Education, 2006 Justice and Humility in Technology Design 1 Abstract Engineeringdesignrequireschoosing betweenvariousdesignalternatives,weighing eachoption basedontechnicaldesigncriteria.Broader criteriahave beensuggestedthatencompassthe cultural,historical,andphilosophicalcontextsinwhichthenewtechnology becomesembedded. Thesecriteria,calleddesignnorms,canonly beappliedeffectively by engineerswithastrong liberaleducation.This paperexaminestwodesignnormsinsomedetail.Thefirstnorm,justice, has beennotedinthe pastasanimportantcriterionfordesigndecisions,butnottosufficient depthtoprovide practicaldesigninsights.Designfor justicerequiresconsiderationofall stakeholdersof adesign.Technologicaldesignscanintrinsicallyleadtoinjustice,forexample, iftheydisrespectstakeholdersorcausediscriminatoryinequities.Thesecondnormexploredin this paper,humility,hastypically beenconsideredagoodqualityoftheengineer,butnotoften appliedtotechnology.Theimplicationsofusing humility as adesigncriterionmightinclude moreemphasisonreliability,userfeedback,andmore -

Plato's Theory of Social Justice in Republic II-IV

Binghamton University The Open Repository @ Binghamton (The ORB) The Society for Ancient Greek Philosophy Newsletter 12-1981 Plato's Theory of Social Justice in Republic II-IV Edward Nichols Lee University of California - San Diego, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://orb.binghamton.edu/sagp Part of the Ancient History, Greek and Roman through Late Antiquity Commons, Ancient Philosophy Commons, and the History of Philosophy Commons Recommended Citation Lee, Edward Nichols, "Plato's Theory of Social Justice in Republic II-IV" (1981). The Society for Ancient Greek Philosophy Newsletter. 120. https://orb.binghamton.edu/sagp/120 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by The Open Repository @ Binghamton (The ORB). It has been accepted for inclusion in The Society for Ancient Greek Philosophy Newsletter by an authorized administrator of The Open Repository @ Binghamton (The ORB). For more information, please contact [email protected]. f J t u a r l tJ. Lee^ W i Y re t* \ - Piulo} A PLATO'S THEORY OF SOCIAL JUSTICE IN REPUBLIC II-IV "Actions speak louder than words." (Old saying) After his long construction of a "city in speech" throughout Books II-IV of the Republic, Plato finally presents, as his long sought-for definition of social justice, the enigmatic and ambiguous formula, "each one doing his own." My main aim in this paper will be to search out the sense that he has esta blished for that definition: to show how he thinks he has established (by the time he unveils it) that that unlikely formula is in fact a reasonable defini tion of social justice, and to analyze what it means (Sections I-III). -

Cultural Representations of the Moors Murderers and Yorkshire Ripper Cases

CULTURAL REPRESENTATIONS OF THE MOORS MURDERERS AND YORKSHIRE RIPPER CASES by HENRIETTA PHILLIPA ANNE MALION PHILLIPS A thesis submitted to the University of Birmingham for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Department of Modern Languages School of Languages, Cultures, Art History, and Music College of Arts and Law The University of Birmingham October 2016 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. Abstract This thesis examines written, audio-visual and musical representations of real-life British serial killers Myra Hindley and Ian Brady (the ‘Moors Murderers’) and Peter Sutcliffe (the ‘Yorkshire Ripper’), from the time of their crimes to the present day, and their proliferation beyond the cases’ immediate historical-legal context. Through the theoretical construct ‘Northientalism’ I interrogate such representations’ replication and engagement of stereotypes and anxieties accruing to the figure of the white working- class ‘Northern’ subject in these cases, within a broader context of pre-existing historical trajectories and generic conventions of Northern and true crime representation. Interrogating changing perceptions of the cultural functions and meanings of murderers in late-capitalist socio-cultural history, I argue that the underlying structure of true crime is the counterbalance between the exceptional and the everyday, in service of which its second crucial structuring technique – the depiction of physical detail – operates. -

September 2016

September 2016 Title – Night Watch Author – Iris Johansen Call Number – F JOHANSEN Book Description - Sometimes, what you can’t see will kill you . Kendra is surprised when she is visited by Dr. Charles Waldridge, the researcher who gave her sight through a revolutionary medical procedure developed by England's Night Watch Project. All is not well with the brilliant surgeon; he’s troubled by something he can’t discuss with Kendra. When Waldridge disappears the very night he visits her, Kendra is on the case, recruiting government agent-for-hire Adam Lynch to join her on a trail that leads to the snow- packed California mountains. There they make a gruesome discovery: the corpse of one of Dr. Waldridge’s associates. But it’s only the first casualty in a white-knuckle confrontation with a deadly enemy who will push Kendra to the limits of her abilities. Soon she must fight for her very survival as she tries to stop the killing…and unearth the shocking secret of Night Watch. Title – Far From True Author – Linwood Barclay Call Number – F BARCLAY Book Description - When private investigator Cal Weaver looks into a break-in at the home of a recently deceased man, he uncovers far more than he is prepared for after he finds a hidden room that was used for salacious activities. Perhaps something illegal . Detective Barry Duckworth is doggedly trying to solve two murders, one of which is three years old. He believes the killings are connected, since each featured a similar distinctive wound. And the key to his mystery may lie with Cal Weaver’s own case. -

Virtues and Vices to Luke E

CATHOLIC CHRISTIANITY THE LUKE E. HART SERIES How Catholics Live Section 4: Virtues and Vices To Luke E. Hart, exemplary evangelizer and Supreme Knight from 1953-64, the Knights of Columbus dedicates this Series with affection and gratitude. The Knights of Columbus presents The Luke E. Hart Series Basic Elements of the Catholic Faith VIRTUES AND VICES PART THREE• SECTION FOUR OF CATHOLIC CHRISTIANITY What does a Catholic believe? How does a Catholic worship? How does a Catholic live? Based on the Catechism of the Catholic Church by Peter Kreeft General Editor Father John A. Farren, O.P. Catholic Information Service Knights of Columbus Supreme Council Nihil obstat: Reverend Alfred McBride, O.Praem. Imprimatur: Bernard Cardinal Law December 19, 2000 The Nihil Obstat and Imprimatur are official declarations that a book or pamphlet is free of doctrinal or moral error. No implication is contained therein that those who have granted the Nihil Obstat and Imprimatur agree with the contents, opinions or statements expressed. Copyright © 2001-2021 by Knights of Columbus Supreme Council All rights reserved. English translation of the Catechism of the Catholic Church for the United States of America copyright ©1994, United States Catholic Conference, Inc. – Libreria Editrice Vaticana. English translation of the Catechism of the Catholic Church: Modifications from the Editio Typica copyright © 1997, United States Catholic Conference, Inc. – Libreria Editrice Vaticana. Scripture quotations contained herein are adapted from the Revised Standard Version of the Bible, copyright © 1946, 1952, 1971, and the New Revised Standard Version of the Bible, copyright © 1989, by the Division of Christian Education of the National Council of the Churches of Christ in the United States of America, and are used by permission. -

Nouvelles Acquisitions

USB NOUVELLES ACQUISITIONS Janvier - février 2018 Cote Titre/Auteur Collection multimédia P - Linguistique et littérature PN 1997 .A1 W279 2013 no.84 Interview with the vampire : the vampire chronicles / [réalisé par Neil Jordan ; scénario de Anne Rice ; production, Studio Geffen Pictures]. PN 1997 .A1 W279 2013 no.85 Seven / [réalisé par David Fincher ; scénario de Andrew Kevin Walker ; production, New Line Cinema]. PN 1997 .A1 W279 2013 no.86 L.A. confidential / [réalisé par Curtis Hanson ; scénario de Curtis Hanson, Brian Helgeland ; adapté du roman de James Ellroy ; production, Regency Enterprises]. PN 1997 .A1 W279 2013 no.87 The matrix / [écrit et réalisé par The Wachowski Brothers ; production, Warner Bros., Village Roadshow Pictures, Silver Pictures]. PN 1997 .A1 W279 2013 no.88 The notebook / [réalisé par Nick Cassavetes ; scénario de Jeremy Leven ; adaptation du roman de Nicholas Sparks par Jan Sardi ; production, New Line Cinema]. PN 1997 .A1 W279 2013 no.89 Million dollar baby / [réalisé par Clint Eastwood ; scénario de Paul Haggis ; basé sur la nouvelle de F.X. Toole ; production, Warner Bros., Malpaso Productions, Lakeshore Entertainment]. PN 1997 .A1 W279 2013 no.90 Harry Potter and the philosopher's stone / [réalisé par Chris Columbus ; scénario de Steven Kloves, basé sur le roman de J.K. Rowling ; production, Warner Bros.]. PN 1997 .A1 W279 2013 no.91 The lord of the rings : the fellowship of the ring / [réalisé par Peter Jackson ; scénario de Fran Walsh, Philippa Boyens, Peter Jackson, d'après l'oeuvre de J. R. R. Tolkien ; production, New Line Cinema, WingNut Films, The Saul Zaentz Company]. PN 1997 .A1 W279 2013 no.92 The lord of the rings : the two towers / [réalisé par Peter Jackson ; scénario de Fran Walsh, Philippa Boyens, Stephen Sinclair, Peter Jackson, d'après l'oeuvre de J. -

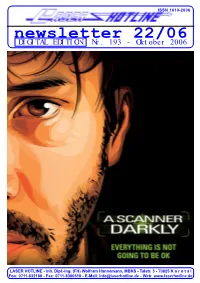

Newsletter 22/06 DIGITAL EDITION Nr

ISSN 1610-2606 ISSN 1610-2606 newsletter 22/06 DIGITAL EDITION Nr. 193 - Oktober 2006 Michael J. Fox Christopher Lloyd LASER HOTLINE - Inh. Dipl.-Ing. (FH) Wolfram Hannemann, MBKS - Talstr. 3 - 70825 K o r n t a l Fon: 0711-832188 - Fax: 0711-8380518 - E-Mail: [email protected] - Web: www.laserhotline.de Newsletter 22/06 (Nr. 193) Oktober 2006 editorial Hallo Laserdisc- und DVD-Fans, diesem Sinne sind wir guten Mutes, unse- liebe Filmfreunde! ren Festivalbericht in einem der kommen- Kennen Sie das auch? Da macht man be- den Newsletter nachzureichen. reits während der Fertigstellung des einen Newsletters große Pläne für den darauf Aber jetzt zu einem viel wichtigeren The- folgenden nächsten Newsletter und prompt ma. Denn wer von uns in den vergangenen wird einem ein Strich durch die Rechnung Wochen bereits die limitierte Steelbook- gemacht. So in unserem Fall. Der für die Edition der SCANNERS-Trilogie erwor- jetzt vorliegende Ausgabe 193 vorgesehene ben hat, der darf seinen ursprünglichen Bericht über das Karlsruher Todd-AO- Ärger über Teil 2 der Trilogie rasch ver- Festival musste kurzerhand wieder auf Eis gessen. Hersteller Black Hill ließ Folgen- gelegt werden. Und dafür gibt es viele gute des verlautbaren: Gründe. Da ist zunächst das Platzproblem. Im wahrsten Sinne des Wortes ”platzt” der ”Käufer der Verleih-Fassung der Scanners neue Newsletter wieder aus allen Nähten. Box haben sicherlich bemerkt, dass der Wenn Sie also bislang zu jenen Unglückli- 59 prall gefüllte Seiten - und das nur mit zweite Teil um circa 100 Sekunden gekürzt chen gehören, die SCANNERS 2 nur in anstehenden amerikanischen Releases! Des ist. -

European Journal of American Studies, 13-2 | 2018 Intertextual Dialogue and Humanization in David Simon’S the Corner 2

European journal of American studies 13-2 | 2018 Summer 2018 Intertextual Dialogue and Humanization in David Simon’s The Corner Mikkel Jensen Electronic version URL: https://journals.openedition.org/ejas/12967 DOI: 10.4000/ejas.12967 ISSN: 1991-9336 Publisher European Association for American Studies Electronic reference Mikkel Jensen, “Intertextual Dialogue and Humanization in David Simon’s The Corner”, European journal of American studies [Online], 13-2 | 2018, Online since 29 June 2018, connection on 08 July 2021. URL: http://journals.openedition.org/ejas/12967 ; DOI: https://doi.org/10.4000/ejas.12967 This text was automatically generated on 8 July 2021. Creative Commons License Intertextual Dialogue and Humanization in David Simon’s The Corner 1 Intertextual Dialogue and Humanization in David Simon’s The Corner Mikkel Jensen 1 From the very beginning it is clear that the HBO miniseries The Corner is a political television series. Its first scene shows its director Charles S. Dutton standing against a wall in Western Baltimore talking about the prevalence of open air drug markets across major cities in America. This is, he tells us, “the information center of the neighborhood” but also “the place of death, of addiction or the suddenness of gunshots.” In Dutton’s words, The Corner is a story about “the men, women, and children living in the midst of the drug trade” whose “voices are too rarely heard” (episode one). By presenting this miniseries as a counter narrative to a media culture that has its focus elsewhere, the show offers its raison d’être in its examination of a group of marginalized people and the circumstances under which they live. -

The Ithacan, 1995-10-05

Ithaca College Digital Commons @ IC The thI acan, 1995-96 The thI acan: 1990/91 to 1999/2000 10-5-1995 The thI acan, 1995-10-05 Ithaca College Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.ithaca.edu/ithacan_1995-96 Recommended Citation Ithaca College, "The thI acan, 1995-10-05" (1995). The Ithacan, 1995-96. 7. http://digitalcommons.ithaca.edu/ithacan_1995-96/7 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the The thI acan: 1990/91 to 1999/2000 at Digital Commons @ IC. It has been accepted for inclusion in The thI acan, 1995-96 by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ IC. OPINION ACCENT SPORTS INDEX Accent .......................... 11 Holding the line An apple a day... Comeback victory Classifieds .................... 16 Comics ......................... 17 College should not extend Apple harvest offers sam Men's soccer team scores Opinion ........................... 8 benefits packages too far 8 pling of local fruits 17 in final minutes to seal win 19 Sports ........................... 19 Thursday, October 5, 1995 The Volume 63, Number 7 24 pages ITHACAN Free The Newspaper For The Ithaca College Community Park bequest used for special programs the request and discussing reasons for the Money left to office of president to provide "The gift is very important for need. for unbudgeted College needs the president to have to be Campus community members can request used to the educational advan these funds from Whalen by letter or by $40,000 a year to the president's office dis contacting him through their dean or direc By Heather Duncan cretionary fund during Park's lifetime. -

Absolute Justice, Kindness and Kinship— the Three Creative Principles By: Hadrat Mirza Tahir Ahmadrh the Fourth Successor of the Promised Messiahas

Absolute Justice, Kindness and Kinship The Three Creative Principles Consists of Four Addresses by Hadrat Mirza Tahir Ahmad Khalifatul Masih IV ISLAM INTERNATIONAL PUBLICATIONS LTD. Absolute Justice, Kindness and Kinship— The Three Creative Principles by: Hadrat Mirza Tahir Ahmadrh The Fourth Successor of the Promised Messiahas First Edition of the first part published in UK (ISBN: 1 85372 567 6) Present Edition comprising all four parts published in UK in 2008 © Islam International Publications Ltd. Published by: Islam International Publications Ltd. 'Islamabad' Sheephatch Lane, Tilford, Surrey GU102AQ United Kingdom. Printed in UK at: Raqeem Press Tilford, Surrey ISBN: 1 85372 741 5 Verily, Allah requires you to abide by justice, and to treat with grace, and give like the giving of kin to kin; and forbids indecency, and manifest evil, and transgression. He admonished you that you may take heed. (Surah al-Nahl; 16:91) Contents About the Author....................................................................vii Introduction ............................................................................ix Publisher’s Note....................................................................xiii Glossary of Terms ...............................................................xvii __________________________________________________ Part I __________________________________________________ ● Foreword to the First Edition of the First Part ● Prologue 1 The Three Creative Principles Defined......................11 Three Stages of Human Relations..................................11