The Future of Ocean Governance and Capacity Development

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Magazine SUMMER 2020 OCEANA.ORG

Magazine SUMMER 2020 OCEANA.ORG Oceana Senior Advisor Alexandra Cousteau and Bloomberg Philanthropies CEO Patti Harris are pictured at the Our Ocean 2019 conference in Oslo, Norway. For more, read the CEO Note on page 3. © Ilja C. Hendel Transparency Crusader (Sea) Food Security COVID-19 and Fisheries Renata Terrazas, Oceana’s VP in The ocean can feed a billion people, Dr. Daniel Pauly explains how fish Mexico, on publicizing vital data but who needs fish most? stocks could recover post-pandemic Board of Directors Ocean Council Oceana Staff Valarie Van Cleave, Chair Susan Rockefeller, Founder Andrew Sharpless Ted Danson, Vice Chair Kelly Hallman, Vice Chair Chief Executive Officer Diana Thomson, Treasurer Dede McMahon, Vice Chair Jim Simon James Sandler, Secretary Anonymous President Keith Addis, President Samantha Bass Gaz Alazraki Violaine and John Bernbach Jacqueline Savitz Chief Policy Officer, North America Monique Bär Rick Burnes Herbert M. Bedolfe, III Vin Cipolla Katie Matthews, Ph.D. Nicholas Davis Barbara Cohn Chief Scientist Sydney Davis Ann Colley César Gaviria Edward Dolman Matthew Littlejohn Senior Vice President, Strategic Initiatives Mária Eugenia Girón Kay and Frank Fernandez Loic Gouzer Carolyn and Chris Groobey Janelle Chanona Jena King J. Stephen and Angela Kilcullen Vice President, Belize Ben Koerner Ann Luskey Ademilson Zamboni, Ph.D. Sara Lowell Mia M. Thompson Vice President, Brazil Stephen P. McAllister Peter Neumeier Kristian Parker, Ph.D. Carl and Janet Nolet Joshua Laughren Daniel Pauly, Ph.D. Ellie Phipps Price Executive Director, Oceana Canada David Rockefeller, Jr. Maria Jose Peréz Simón Liesbeth van der Meer Susan Rockefeller David Rockefeller, Jr. Vice President, Chile Simon Sidamon-Eristoff Elias Sacal Rashid Sumaila, Ph.D. -

The Cultural Ecology of Elisabeth Mann Borgese

NARRATIVES OF NATURE AND CULTURE: THE CULTURAL ECOLOGY OF ELISABETH MANN BORGESE by Julia Poertner Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at Dalhousie University Halifax, Nova Scotia March 2020 © Copyright by Julia Poertner, 2020 TO MY PARENTS. MEINEN ELTERN. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT ………………………………………………………………………………... v LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS USED ………………………………………………………….. vi ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ………………………………………………………………….. vii CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION ……………………………………………………………… 1 1.1 Thesis ………………………………………………………………... 1 1.2 Methodology and Outline ………………………………………….. 27 1.3 State of Research ……....…………………………………………... 32 1.4 Background ……………………………………………………….... 36 CHAPTER 2: NARRATIVES OF NATURE AND CULTURE …………………………………... 54 2.1 Between a Mythological Past and a Scientific Future ……………………. 54 2.1.1 Biographical Background ………………………………………... 54 2.1.2 “Culture is Part of Nature in Any Case”: Cultural Evolution ……. 63 2.1.3 Ascent of Woman ………………………………….……………… 81 2.1.4 The Language Barrier: Beasts and Men …….…………………… 97 2.2 Dark Fiction: Futuristic Pessimism …………………………………….. 111 2.2.1 “To Whom It May Concern” ………………….………………… 121 2.2.2 “The Immortal Fish” ………………………………………….…. 123 2.2.3 “Delphi Revisited” ……………………………………….……… 127 2.2.4 “Birdpeople” …………………………………………….………. 130 CHAPTER 3: UTOPIAN OPTIMISM: THE OCEAN AS A LABORATORY FOR A NEW WORLD ORDER ……………………………………………….…………….……… 135 3.1 Historical Background …………………………………………………. 135 3.1.1 Competing Narratives: The Common Heritage of Mankind and Sustainable Development ……………………………………….. 135 3.1.2 Ocean Frontiers and Chairworm & Supershark ………………... 175 3.1.3 Arvid Pardo’s Tale of the Deep Sea …………………………….. 184 3.2 Elisabeth Mann Borgese’s Cultural Ecology ………………………….. 207 iii 3.2.1 Law: From the Deep Seabed via Ocean Space towards World Communities ……………………………………………………. 207 3.2.2 Economics ………………………………………………………. 244 3.2.3 Science and Education: The Need for Interdisciplinarity ………. -

2-4 September 2010

INTERNATIONAL FORUM ON SUSTAINABLE GOVERNANCE OF THE OCEAN: IMPACTS OF CLIMATE CHANGE & OCEAN RELATED HAZARDS: WATER & FLOOD MANAGEMENT POLICY IMPLICATIONS, PROTECTION, MITIGATION & ADAPTATION; & FOLLOW UP OF THE OUTCOME OF RIO +20: IMPLEMENTATION OF UNCLOS & RELATED INSTRUMENTS IN THE SOUTHEAST ASIAN REGION; AND INTERNET WEB-BASED GEOGRAPHICAL INFORMATION SYSTEM Centara Grand at Central Plaza Ladprao Bangkok, Thailand 3rd to 8th September 2013 HANDBOOK & PROGRAMME PARTNERS Aquatic Resources Research Institute (ARRI) Association of Natural Disaster Prevention Industry (ANDPI); Chulalongkorn University; Bay of Bengal Large Marine Ecosystem Project (BOBLME), Coastal Development Center (CDC), Thailand; Faculty of Fisheries, Kasetsart University; Department of Fisheries (DOF), Department of Marine and Coastal Resources (DMCR), Ministry of Agriculture and Cooperatives; Ministry of Natural Resources; Fondation de Malte; Foundation of National Disaster Warning Council (FNDWC); High Seas Alliance; Institute of Earth Systems (IES), University of Malta; PACEM IN MARIBUS XXXIV | 1 Future Ocean Kiel Marine Sciences; Miyamoto International, Inc.; Office of National Water and Flood Management Policy (ONWF), Pacific Disaster Center (PDC); Office of the Prime Minister’s Secretariat; Partnerships in Environmental Management Southeast Asian Fisheries Development Center (SEAFDEC); for the Seas of East Asia (PEMSEA); Thailand’s National Disaster Warning Center (NDWC), Ministry of Information and Communication Technology; The International Emergency Management Society (TIEMS); Tsunami Society International 2 | PACEM IN MARIBUS XXXIV SPONSORS Asia Dhanawat Warehouse Co. Ltd. Thailand LPN Dock & Engineering Co. Ltd. Office of National Water and Flood Management Policy (ONWF), Office of the Prime Minister’s (บ.อูเ่ รือแอลพีเอน็ วศิ วกรรม จำ กดั ) PACEM IN MARIBUS XXXIV | 3 Introduction The 34rd Pacem in Maribus is taking place at a time of great challenge to the international community. -

Proposal to Encode Heterodox Chess Symbols in the UCS Source: Garth Wallace Status: Individual Contribution Date: 2016-10-25

Title: Proposal to Encode Heterodox Chess Symbols in the UCS Source: Garth Wallace Status: Individual Contribution Date: 2016-10-25 Introduction The UCS contains symbols for the game of chess in the Miscellaneous Symbols block. These are used in figurine notation, a common variation on algebraic notation in which pieces are represented in running text using the same symbols as are found in diagrams. While the symbols already encoded in Unicode are sufficient for use in the orthodox game, they are insufficient for many chess problems and variant games, which make use of extended sets. 1. Fairy chess problems The presentation of chess positions as puzzles to be solved predates the existence of the modern game, dating back to the mansūbāt composed for shatranj, the Muslim predecessor of chess. In modern chess problems, a position is provided along with a stipulation such as “white to move and mate in two”, and the solver is tasked with finding a move (called a “key”) that satisfies the stipulation regardless of a hypothetical opposing player’s moves in response. These solutions are given in the same notation as lines of play in over-the-board games: typically algebraic notation, using abbreviations for the names of pieces, or figurine algebraic notation. Problem composers have not limited themselves to the materials of the conventional game, but have experimented with different board sizes and geometries, altered rules, goals other than checkmate, and different pieces. Problems that diverge from the standard game comprise a genre called “fairy chess”. Thomas Rayner Dawson, known as the “father of fairy chess”, pop- ularized the genre in the early 20th century. -

Science Fiction Review 29 Geis 1979-01

JANUARY-FEBRUARY 1979 NUMBER 29 SCIENCE FICTION REVIEW $1.50 NOISE LEVEL By John Brunner Interviews: JOHN BRUNNER MICHAEL MOORCOCK HANK STINE Orson Scott Card - Charles Platt - Darrell Schweitzer Elton Elliott - Bill Warren SCIENCE FICTION REVIEW Formerly THE ALIEN CRITIC RO. Bex 11408 COVER BY STEPHEN FABIAN January, 1979 — Vol .8, No.l Based on a forthcoming novel, SIVA, Portland, OR WHOLE NUMBER 29 by Leigh Richmond 97211 ALIEN TOUTS......................................3 RICHARD E. GEIS, editor & piblisher SUBSCRIPTION INFORMATION INTERVIEW WITH JOHN BRUWER............. 8 PUBLISHED BI-MONTHLY CONDUCTED BY IAN COVELL PAGE 63 JAN., MARCH, MAY, JULY, SEPT., NOV. NOISE LEVEL......................................... 15 SINGLE COPY ---- $1.50 A COLUMN BY JOHN BRUNNER REVIEWS-------------------------------------------- INTERVIEW WITH MICHAEL MOORCOCK.. .18 PHOfC: (503) 282-0381 CONDUCTED BY IAN COVELL "seasoning" asimov's (sept-oct)...27 "swanilda 's song" analog (oct)....27 THE REVIEW OF SHORT FICTION........... 27 "LITTLE GOETHE F&SF (NOV)........28 BY ORSON SCOTT CARD MARCHERS OF VALHALLA..............................97 "the wind from a burning WOMAN ...28 SKULL-FACE....................................................97 "hunter's moon" analog (nov).....28 SON OF THE WHITE WOLF........................... 97 OCCASIONALLY TENTIONING "TUNNELS OF THE MINDS GALILEO 10.28 SWORDS OF SHAHRAZAR................................97 SCIENCE FICTION................................ 31 "the incredible living man BY DARRELL SCHWEITZER BLACK CANAAN........................................ -

The Role of Reservations and Vetoes in Marine Conservation Agreements

The Role of Reservations and Vetoes in Marine Conservation Agreements Howard S. Schiffman A thesis submitted in partial satisfaction of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Professor Robin R. Churchill, Supervisor Cardiff Law School Cardiff University Submitted, July 3, 2006 \ ~ . lv UMI Number: U585553 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U585553 Published by ProQuest LLC 2013. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 The Role of Reservations and Vetoes in Marine Conservation Agreements Howard S. Schiffman Contents Preface...................................................................................................................iv Acknowledgements ..............................................................................................v List of Abbreviations ...........................................................................................viii Chapter 1 “Exemptive Provisions:” A Survey of the Issues in International Law 1 I. Introduction ............................................................................................ -

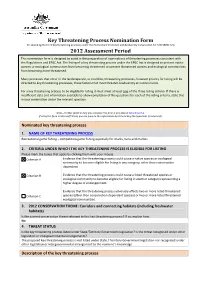

Key Threatening Process Nomination Form

Key Threatening Process Nomination Form for amending the list of key threatening processes under the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (EPBC Act) 2012 Assessment Period This nomination form is designed to assist in the preparation of nominations of threatening processes consistent with the Regulations and EPBC Act. The listing of a key threatening process under the EPBC Act is designed to prevent native species or ecological communities from becoming threatened or prevent threatened species and ecological communities from becoming more threatened. Many processes that occur in the landscape are, or could be, threatening processes, however priority for listing will be directed to key threatening processes, those factors that most threaten biodiversity at national scale. For a key threatening process to be eligible for listing it must meet at least one of the three listing criteria. If there is insufficient data and information available to allow completion of the questions for each of the listing criteria, state this in your nomination under the relevant question. Note – Further detail to help you complete this form is provided at Attachment A. If using this form in Microsoft Word, you can jump to this information by Ctrl+clicking the hyperlinks (in blue text). Nominated key threatening process 1. NAME OF KEY THREATENING PROCESS Recreational game fishing – competition game fishing especially for sharks, tuna and marlins 2. CRITERIA UNDER WHICH THE KEY THREATENING PROCESS IS ELIGIBLE FOR LISTING Please mark the boxes that apply by clicking them with your mouse. Criterion A Evidence that the threatening process could cause a native species or ecological community to become eligible for listing in any category, other than conservation dependent. -

Wehrli-Introsandtexts FINAL.Docx

Catalog of Everything and Other Stories Peter K. Wehrli Edited by Jeroen Dewulf, in cooperation with Anna Carlsson, Ann Huang, Adam Nunes and Kevin Russell eScholarship – University of California, Berkeley Department of German Published by eScholarship and Lulu.com University of California, Berkeley, Department of German 5319 Dwinelle Hall, Berkeley, CA 94720 Berkeley, USA © Peter K. Wehrli (text) © Arrigo Wittler (front cover painting Porträt Peter K. Wehrli, Forio d’Ischia 1963) © Rara Coray (back cover image) All Rights Reserved. Published 2014 Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 978-1-304-96040-5 Table of Contents Introduction 1 I. Everything is a Reaction to Dada 9 II. Robby and Alfred 26 III. Burlesque 32 IV. Hearty Home Cooking 73 V. Travelling to the Contrary of Everything 85 VI. The Conquest of Sigriswil 103 VII. Catalog of Everything I: Catalog of the 134 Most Important Observations During a Long Railway Journey 122 VIII. Catalog of Everything II: 65 Selected Numbers 164 IX. Catalog of Everything III: The Californian Catalog 189 Contributors 218 Introduction Peter K. Wehrli was born in 1939 in Zurich, Switzerland. His father, Paul Wehrli, was secretary for the Zurich Theatre and also a writer. Encouraged by his father to respect and appreciate the arts, the young Peter Wehrli enthusiastically rushed through homework assignments in order to attend as many theater performances as possible. Wehrli later studied Art History and German Studies at the universities of Zurich and Paris. As a student, he used to frequent the Café Odeon in downtown Zurich, where many famous intellectuals and artists used to meet. -

Global Oceans Governance: New and Emerging Issues

EG41CH02-Campbell ARI 22 June 2016 10:35 V I E Review in Advance first posted online E W on July 6, 2016. (Changes may R S still occur before final publication online and in print.) I E N C N A D V A Global Oceans Governance: New and Emerging Issues Lisa M. Campbell,1 Noella J. Gray,2 Luke Fairbanks,1 Jennifer J. Silver,2 Rebecca L. Gruby,3 Bradford A. Dubik,1 and Xavier Basurto1 1Nicholas School of the Environment, Duke University Marine Lab, Beaufort, North Carolina 28516; email: [email protected] 2Department of Geography, University of Guelph, Guelph, Ontario NIG 2W1, Canada 3Department of Human Dimensions of Natural Resources, Colorado State University, Fort Collins, Colorado 80523 Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2016. 41:2.1–2.27 Keywords The Annual Review of Environment and Resources is Access provided by Duke University on 08/08/16. For personal use only. food production, industrialization, biodiversity conservation, global online at environ.annualreviews.org environmental change, pollution Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2016.41. Downloaded from www.annualreviews.org This article’s doi: 10.1146/annurev-environ-102014-021121 Abstract Copyright c 2016 by Annual Reviews. Increased interest in oceans is leading to new and renewed global governance All rights reserved efforts directed toward ocean issues in areas of food production, biodiversity conservation, industrialization, global environmental change, and pollution. Global oceans governance efforts face challenges and opportunities related to the nature of oceans and to actors involved in, the scale of, and knowl- edge informing their governance. We review these topics generally and in relation to nine new and emerging issues: small-scale fisheries (SSFs), aqua- culture, biodiversity conservation on the high seas, large marine protected areas (LMPAs), tuna fisheries, deep-sea mining, ocean acidification (OA), blue carbon (BC), and plastics pollution. -

World History Bulletin Fall 2016 Vol XXXII No

World History Bulletin Fall 2016 Vol XXXII No. 2 World History Association Denis Gainty Editor [email protected] Editor’s Note From the Executive Director 1 Letter from the President 2 Special Section: The World and The Sea Introduction: The Sea in World History 4 Michael Laver (Rochester Institute of Technology) From World War to World Law: Elisabeth Mann Borgese and the Law of the Sea 5 Richard Samuel Deese (Boston University) The Spanish Empire and the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans: Imperial Highways in a Polycentric Monarchy 9 Eva Maria Mehl (University of North Carolina Wilmington) Restoring Seas 14 Malcolm Campbell (University of Auckland) Ship Symbolism in the ‘Arabic Cosmopolis’: Reading Kunjayin Musliyar’s “Kappapattu” in 18th Century Malabar 17 Shaheen Kelachan Thodika (Jawaharlal Nehru University) The Panopticon Comes Full Circle? 25 Sarah Schneewind (University of California San Diego) Book Review 29 Abeer Saha (University of Virginia) practical ideas for the classroom; she intro- duces her course on French colonialism in Domesticating the “Queen of Haiti, Algeria, and Vietnam, and explains how Beans”: How Old Regime France aseemingly esoteric topic like the French empirecan appear profoundly relevant to stu- Learned to Love Coffee* dents in Southern California. Michael G. Vann’sessay turns our attention to the twenti- Julia Landweber eth century and to Indochina. He argues that Montclair State University both French historians and world historians would benefit from agreater attention to Many goods which students today think of Vietnamese history,and that this history is an as quintessentially European or “Western” ideal means for teaching students about cru- began commercial life in Africa and Asia. -

Ocean Governance and Its Implementation, All of Which May Be Applicable in the Context of the Arctic Council’S Work

O CEA N GOVERNANCE AN D ITS IM PLEM ENTATION: GU IDIN G PRINCIPLES FO R THE ARCTIC REGIO N 1 Dr. François N. Bailet2 TABLE OF CONTENT INTORDUCTION: MANIFESTATIONS OF OCEAN GOVERNANCE............................................... 2 THE GUIDEING PRINCIPLES OF OCEAN GOVERNANCE ........................................................... 3 LEVELS OF IMPLEMENTATION OF OCEAN GOVERNANCE ....................................................... 6 CONCLUSION............................................................................................................................. 19 This background paper is intended to serve as an information piece which outlines Ocean Governance Theory, as envisioned by the late Elisabeth Mann Borgese, and as it may be applicable to the Arctic Region in support of the Arctic Council’s (PAME) work in the elaboration of an Arctic Marine Strategic Plan. It is not the intent of this paper to review the current status of legal, political and institutional approaches to the management of Arctic resources and activities. These topics are extensively reviewed in the current literature and numerous relevant subject experts may contribute directly to the work of the Arctic Council.3 It is also not the intent of this paper to provide a prescriptive commentary on an approach to adopt in the Arctic Region. The contents of this paper are thus solely intended to contribute to the relevant discussions by providing an overview of Ocean Governance and its Implementation, all of which may be applicable in the context of the Arctic -

A Comparative Study of Three Regional

Effective Governance and Policy Implementation in Governing High Seas Fisheries: A Comparative Study of Three Regional Fisheries Management Organizations By Jia Huey Hsu A thesis submitted to the Victoria University of Wellington in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Victoria University of Wellington 2018 Abstract Two-thirds of fish stocks commercially fished on the high seas are either depleted or overexploited. Regional Fisheries Management Organizations (RFMOs) are key international actors having the legal competence to establish fishery conservation and management measures to improve the optimal and sustainable utilization of high seas fisheries resources. The literature suggests that their effectiveness is varied. While some RFMOs are making progress towards more sustainable fisheries, some are facing fish stock depletion. The literature indicates that organizational governance design and quality of implementation are central to the disparities. Thus far, while most of the discussion has focused on the effectiveness, and how to enhance the transparency of RFMOs, very little research has explored the designs of governance arrangements and implementation of RFMOs. Accordingly, this study contributes to the literature on governance arrangements and policy implementation of the high seas by offering in-depth case studies of the selected RFMOs. It employs qualitative methods to analyze data collected from semi-structured interviews with 24 actors (i.e., officials, delegations, and fisheries experts), as well as a collection of published and unpublished documents regarding three selected RFMOs. The three selected RFMOs are the Commission for the Conservation of Southern Bluefin Tuna (CCSBT), the Western and Central Pacific Fisheries Commission (WCPFC), and the South Pacific Regional Fisheries Management Organization (SPRFMO).