CAUSE NO. § § § V

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Station City Title Year Accomplishment KARE-TV

Station City Title Year Accomplishment KARE-TV Minneapolis 2001 Overall Excellence KARE-TV Minneapolis 2000 Overall Excellence KARE-TV Minneapolis 2000 Feature Reporting KARE-TV Minneapolis 2000 News Documentary KARE-TV Minneapolis 2000 Sports Reporting KARE-TV Minneapolis 2000 Spot News Coverage KARE-TV Minneapolis 2001 Overall Excellence KARE-TV Minneapolis The Bitter Pill 2001 Investigative Reporting KARE-TV Minneapolis KARE 11 News at 10 p.m. 2001 Newscast KARE-TV Minneapolis Fishing for Love 2001 Use of Video KATU-TV Portland, OR 2000 Continuing Coverage KCBS-TV Los Angeles California's Billion Dollar Rip Off 2001 News Series KCBS-TV Los Angeles 2000 Investigative Reporting KCBS-TV Los Angeles 2000 News Series KCBS-TV Los Angeles California's Billion Dollar Ripoff 2001 News Series KCNC-TV Denver Erin's Live3/4 10 Years Later 2001 Feature Reporting KCNC-TV Denver 2000 Spot News Coverage KCNC-TV Denver 2000 Use of Video KCNC-TV Denver Erin's Live - Ten Years Later 2001 Feature Reporting KCNC-TV Denver Houseboat Investigation 2001 Investigative Reporting KCOP-TV Los Angeles 2000 Continuing Coverage KCOP-TV Los Angeles Marlin Briscoe 2001 Sports Reporting KCRA-TV Sacramento 2000 Newscast KENS-TV San Antonio Tommy Lynn Sells 2001 Continuing Coverage KGTV San Diego Electric Shock 2001 Continuing Coverage KGW-TV Portland, OR Michael's Big Game 2001 Feature Reporting KGW-TV Portland, OR Vermiculite Investigation 2001 News Series KGW-TV Portland, OR kgw.com 2001 Web Site KHOU-TV Houston Treading On Danger 2001 Investigative Reporting KHOU-TV -

Dale Hansen , Sports Anchor, WFAA 8

The Rotary Club THE HUB of Park Cities Volume 71, Number 25 www.parkcitiesrotary.org February 14, 2020 Serving to Make a Difference Since 1948 TODAY’S PROGRAM Program Chairs of the Day: Jeff Brady Dale Hansen, Sports Anchor, WFAA 8 Dale Hansen is the weeknight sports anchor during the 10 Hansen's other awards and honors include: p.m. newscast on WFAA, Channel 8 in Dallas Texas. He also • Dallas Peace and Justice Center's 2019 Inspiration Award hosts Dale Hansen's Sports Special on Sundays at 10:35 p.m.. • Hero of Hope Award from the Cathedral of Hope Church He's well known for his acclaimed "Unplugged" segments. • Peacemaker Award from the Turtle Creek Chorale Hansen began his career as a radio disc jockey and opera- • Children's Hero Award from TexProtects tions manager in Newton, Iowa. This was followed by a job as a • Distinguished Professional Achievement Award from the UNT sports reporter at KMTV in Omaha, Nebraska. Hansen's first job School of Journalism in Dallas was with KDFW-TV (Channel 4). He joined WFAA-TV in • Communicator of the Year by the National Speech and Debate 1983. Association In 1987, Hansen was honored with the George Foster Pea- • Recipient of over 20 Lone Star EMMY Awards body Award for Distinguished Journalism. That same year, he won • Sportscaster of the Year on two occasions by the Associated the duPont-Columbia Award for his contribution to the investiga- Press tion of SMU's football program. As a result of this investigation, • Texas Sportscaster of the Year on three occasions by the the NCAA prohibited SMU from fielding a football program in 1987. -

Formerly KJAC) KFDM-TV, 6, Beaumont, TX KBMT, 12, Beaumont, TX +KW,29, Lake Charles, LA

Federal Communications Commission FCC 05-24 Newton KBTV-TV,4, Port Arthur, TX (formerly KJAC) KFDM-TV, 6, Beaumont, TX KBMT, 12, Beaumont, TX +KW,29, Lake Charles, LA Nolan KRBC-TV, 9, Abilene, TX KTXS-TV, 12, Sweetwater, TX +KTAB-TV, 32, Abilene, TX Nueces KIII-TV, 3, Corpus Chri~ti,TX KRIS-TV, 6, Corpus Christi, TX KZTV, 10, corpus christi, TX Ochiltree KAMR-TV, 4, Amarillo, TX (formerly KGNC) KW-TV, 7, Amarillo, TX KFDA-TV, 10, Amarillo, TX Oldham KAMR-TV, 4, Amarillo, TX (formw KGNC) KW-TV, 7, Amarillo, TX KFDA-TV, 10, Amarillo, TX Orange KBTV-TV, 4, Port Arthur, TX (formerly KJAC) KFDM-TV, 6, Beaumont, TX KBMT, 12, Beaumont, TX +KV", 29, Lake Charles, LA Palo Pinto KDFW-TV,4, Dallas, TX KXAS-TV, 5, Fort Worth, TX (formerly WAP) WFAA-TV,8, Dallas, TX KTVT, 11, Fort Worth,TX Panola KTBS-TV, 3, Shreveport, LA KTAL-TV, 6, Shreveport, LA KSLA-TV, 12, Shreveport, LA +KMSS-TV, 33, Shreveport, LA Parker KDFW-TV,4, Dallas, TX KXAS-TV,5, Fort Worth, TX (formerly MAP) WFAA-TV,8, Dallas, TX KTVT, 11, Fort Worth, TX 397 Federal CommunicatiOns Commiukm FCC 05-24 P- KAMR-TV, 4, Amanllo, TX (formerly KGNC) KW-TV, 7, Amarillo, TX KFDA-TV, 10, Amarillo, TX KCBD-TV, 11, Lubbock, TX Pews KMJD, 2, Midland, TX KOSA-TV,7, Odessa, TX KWES-TV, 9, Odessa, TX (formerly KMOM) Polk KTRE,9, Lufkin, TX KBTV-TV, 4, Port Arthur, TX (formerly WAC) KFDM-TV,6, Beaumont, "X KPRC-TV, 2, HoustoR TX +KTXH, 20, Houston, TX Potter KAMR-TV, 4, Amarillo, TX (formerly KGNC) KW-TV,7, Amarillo, TX KFDA-TV, 10, Amarillo, TX +KCIT, 14, Amarillo, TX presidio KOSA-TV, 7, TX bins -

Frontier Fiberoptic TV Texas Business Channel Lineup and TV Guide

Frontier® FiberOptic TV for Business Texas Business Channel Lineup Effective September 2021 Welcome to Frontier ® FiberOptic TV for Business Got Questions? Get Answers. Whenever you have questions or need help with your Frontier TV service, we make it easy to get the answers you need. Here’s how: Online, go to Frontier.com/helpcenter to find the Frontier User Guides to get help with your Internet and Voice services, as well as detailed instructions on how to make the most of your TV service. Quick Reference Channels are grouped by programming categories in the following ranges: Local Channels 1–49 SD, 501–549 HD Local Public/Education/Government (varies by 15–47 SD location) Entertainment 50–69 SD, 550–569 HD News 100–119 SD, 600–619 HD Info & Education 120–139 SD, 620–639 HD Home & Leisure/Marketplace 140–179 SD, 640–679 HD Pop Culture 180–199 SD, 680–699 HD Music 210–229 SD, 710–729 HD Movies/Family 230–249 SD, 730–749 HD Kids 250–269 SD, 780–789 HD People & Culture 270–279 SD Religion 280–299 SD Premium Movies 340–449 SD, 840–949 HD* Subscription Sports 1000–1499* Spanish Language 1500–1760 * Available for Private Viewing only 3 Local TV KUVN (Univision) 23/523 HD Local channels included in all KXAS (Cozi TV) 460 TV packages. KXAS (NBC) 5/505 HD Dallas/Ft Worth, TX KXAS (NBC Lx) 461 C-SPAN 109/ 1546 HD KXTX (Telemundo) 10/510 HD Jewelry Television 56/152 HD KXTX (TeleXitos) 470 HSN 12/ 512 HD QVC 6/506 HD KAZD (Me TV) 3/ 503 HD WFAA (ABC) 8/508 HD KCOP (Heroes & Icons) 467 WFAA (True Crime 469 KDAF (Antenna TV) 463 Network) KDAF (CW) 9/509 HD WFAA (Twist) 482 KDAF (Court TV) 462 Texas Regional Sports KDFI (Buzzr) 487 Channels KDFI (My 27) 7/507 HD Longhorn Network 79/579 HD KDFI (Movies!) 477 SEC Network 75/575 HD KDFW (Fox) 4/504 HD SEC Network Overflow 332/832 HD SEC Network Overflow KDTN (Daystar) 2 333 2 KDTX (TBN) 17/517 HD KERA (PBS) 13/513 HD KFWD (Independent) 14/514 HD Custom Essentials TV Local TV channels included, Regional KMPX (Estrella) 29/529 HD Sports not included. -

John Alexander

John Alexander 1945 Born in Beaumont, Texas EDUCATION 1970 M.F.A. from Southern Methodist University, Dallas, Texas 1968 B.F.A. from Lamar University, Beaumont, Texas SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2011 John Alexander: One World: Two Artists, Ogden Museum of Southern Art, New Orleans, LA John Alexander: Paintings, J. Johnson Gallery, Jacksonville, FL John Alexander: John Alexander and Walter Anderson, One World: Two Artists, The University of Mississippi Museum, Oxford, MS 2010 John Alexander, McClain Gallery, Houston, TX 2009 John Alexander, Arthur Roger Gallery, New Orleans, LA 2008 John Alexander: Drawings. Hemphill Fine Art, Washington DC John Alexander: A Retrospective. Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, TX John Alexander: New Paintings, McClain Gallery, Houston, TX John Alexander. Drawing Room, East Hampton, NY John Alexander: New Drawings, McClain Gallery, Houston, TX John Alexander: Recent Paintings, Imago Galleries, Palm Desert, CA 2007 John Alexander: New Works on Paper. Eaton Fine Art, West Palm Beach, FL John Alexander: A Retrospective. Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington DC 2006 John Alexander, Arthur Roger Gallery, New Orleans, LA 2005 John Alexander: The Sea! The Sea!, Eaton Fine Art, West Palm Beach, FL John Alexander: Recent Observations, The Butler Institute of American Art. Youngstown, OH 2004 John Alexander, J. Johnson Gallery, Jacksonville Beach, FL John Alexander, Bentley, Gallery, Scottsdale, AZ 2003 Dishman Gallery of Art, Lamar University, Beaumont, TX JA: 35 Years of Works on Paper. Art Museum of Southeast Texas, Beaumont, -

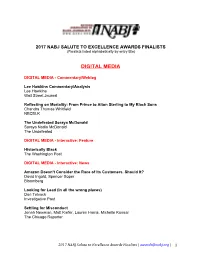

Digital Media

2017 NABJ SALUTE TO EXCELLENCE AWARDS FINALISTS (Finalists listed alphabetically by entry title) DIGITAL MEDIA DIGITAL MEDIA - Commentary/Weblog Lee Hawkins Commentary/Analysis Lee Hawkins Wall Street Journal Reflecting on Mortality: From Prince to Alton Sterling to My Black Sons Chandra Thomas Whitfield NBCBLK The Undefeated Soraya McDonald Soraya Nadia McDonald The Undefeated DIGITAL MEDIA - Interactive: Feature Historically Black The Washington Post DIGITAL MEDIA - Interactive: News Amazon Doesn’t Consider the Race of Its Customers. Should It? David Ingold, Spencer Soper Bloomberg Looking for Lead (in all the wrong places) Dan Telvock Investigative Post Settling for Misconduct Jonah Newman, Matt Kiefer, Lauren Harris, Michelle Kanaar The Chicago Reporter 2017 NABJ Salute to Excellence Awards Finalists | [email protected] | 1 DIGITAL MEDIA > Online Project: Feature The City: Prison's Grip on the Black Family Trymaine Lee NBC News Digital Under Our Skin Staff of The Seattle Times The Seattle Times Unsung Heroes of the Civil Rights Movement Eric Barrow New York Daily News DIGITAL MEDIA > Online Project: News Chicago's disappearing front porch Rosa Flores, Mallory Simon, Madeleine Stix CNN Machine Bias Julia Angwin, Jeff Larson, Surya Mattu, Lauren Kirchner, Terry Parris Jr. ProPublica Nuisance Abatement Sarah Ryley, Barry Paddock, Pia Dangelmayer, Christine Lee ProPublica and The New York Daily News DIGITAL MEDIA > Single Story: Feature Congo's Secret Web of Power Michael Kavanagh, Thomas Wilson, Franz Wild Bloomberg Migration and Separation: -

REGISTER NOW �Station Summit: Las Vegas

�Awards: North America Station 2019. 1 Celebrate the best in television station marketing. REGISTER NOW �Station Summit: Las Vegas. June 17-21, 2019. �Awards: North America Station 2019. GENERAL BRANDING/IMAGE: NEWS STATION IMAGE - SMALL MARKET GOO GOO DOLLS - TURN IT UP WGRZ KHQ STATION IMAGE 2018 KHQ TV ALL DEVICES WWBT CHANGE IS COMING WLTX-TV 65 YEARS THROUGH OUR LENS WIBW-TV PRESCRIBING HOPE HAWAII NEWS NOW/GRAY TELEVISION GENERAL BRANDING/IMAGE: NEWS STATION IMAGE - MEDIUM MARKET COLUMBUS, MY HOME WBNS-10TV CBS AUSTIN- CENTRAL TEXAS TRUSTED - WORKING SINCLAIR BROADAST GROUP THE SOURCE WDRB MEDIA WE ARE ONE WHAS11/TEGNA CBS 58 ELEVATOR WEIGEL BROADCASTING WDJT MILWAUKEE WDSU 70TH ANNIVERSARY WDSU-TV 2 Celebrate the best in television station marketing. REGISTER NOW �Station Summit: Las Vegas. June 17-21, 2019. �Awards: North America Station 2019. GENERAL BRANDING/IMAGE: NEWS STATION IMAGE - LARGE MARKET FIRE AND ICE KGW DEMANDING NBC10 BOSTON WBZ: ONE 4 ALL WBZ-TV I AM THUNDER KXAS BRAND MARKETING STRONGER AND BETTER TOGETHER NBC4 LA STORM FLEET 2.0 KXAS BRAND MARKETING, PLANET 365 GENERAL BRANDING/IMAGE CAMPAIGN - SMALL MARKET WORKING FOR YOU WTVR STORIES THAT MAKE AN IMPACT WPRI YOU KNOW THIS IS HOME WHEN WGRZ PM IMAGE WWBT WWBT THV11 STORYTELLERS KTHV MORNING ON REPEAT WATERMAN BROADCASTING 3 Celebrate the best in television station marketing. REGISTER NOW �Station Summit: Las Vegas. June 17-21, 2019. �Awards: North America Station 2019. GENERAL BRANDING/IMAGE CAMPAIGN - MEDIUM MARKET WISH-TV - LOCAL NEWS SOURCE LAUNCH CAMPAIGN WISH-TV STORIES OF NOW TEGNA- 13NEWS NOW (WVEC) TRIBUNE MEDIA - FOX4 TALENT CAMPAIGN TRIBUNE MEDIA HERE FOR YOU WWL-TV BUILD YOU UP KSL TV WTKR NEWS 3 - MORNING PERSON TRIBUNE BROADCASTING GENERAL BRANDING/IMAGE CAMPAIGN - LARGE MARKET HOT FOR TV WCIU KTLA 5 NEWS IMAGE CAMPAIGN: CUT TO LA KTLA 70 YEARS OF STORIES KPIX MEDIA WITH IMPACT WNET EMOTIONAL COLORS KARE 11 I AM CAMPAIGN WFAA, A TEGNA COMPANY 4 Celebrate the best in television station marketing. -

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE May 6, 2021 TEGNA Honored with 86

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE May 6, 2021 TEGNA Honored with 86 Regional Edward R. Murrow Awards, Including Six for Excellence in Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion Tysons, VA – TEGNA Inc. (NYSE: TGNA) today announced its stations received 86 Regional Edward R. Murrow Awards – more than any other local broadcast television group – for excellence in broadcast journalism, including the coveted prizes for overall excellence, excellence in innovation, and the new category of excellence in diversity, equity, and inclusion. More than a third of TEGNA’s 64 stations were among the winners with four stations – KARE, KING, WFAA and WUSA – garnering overall excellence, the highest honor awarded. Seven TEGNA stations – KGW, KUSA, KSDK, NEWS CENTER Maine, WFAA and WGRZ – also won for excellence in innovation, which recognizes “news organizations that innovate their product to enhance the quality of journalism and the audience’s understanding of news.” In addition, six TEGNA stations – KARE, KGW, KSDK, WFAA, WWL and WXIA – received the Edward R. Murrow’s newest honor – excellence in diversity, equity, and inclusion – which is given for “outstanding advocacy journalism tackling the topic of diversity, racial injustice and/or inequality.” “TEGNA’s commitment to exceptional journalism has once again been recognized by the prestigious Regional Edward R. Murrow awards,” said Dave Lougee, president and CEO, TEGNA. “As our nation continues to confront acts of racial and social injustice, we are especially proud that our stations are recognized for covering and facilitating important discussions about race and inequality that will help drive systemic change.” Overall, 24 TEGNA stations were honored, with 10 awarded to KARE; nine to KUSA; eight to WFAA; seven to KDSK; six to KING and WXIA; four to KGW, NEWS CENTER Maine and WHAS; three to WBIR, WGRZ, WUSA, WTHR and WWL; two to KHOU, KXTV, WOI and WTC; and one each to First Coast News, KPNX, KTVB, KWES, WTOL and WVEC. -

Dallas Papers and Truth

EIS Page Two CA4—.C,74Vt4 „ Editor Penn Jones Jr. Publisher The Midlothian Mirror, In "The Only 'History of Midlothian' Being Written" PUBLISHED EVERY THURSDAY. Second-class postage paid at Midlothian, Texas. 76065. Office of publication is 214 West Avenue F Midlothian, Texas 76065. Any erroneous reflection upon the character, standing or reputation of any .person, firm or corporation, appearing in the columns of The Mirror will fully and gladly be corrected upon being brought to the attention of the editor of this paper. SUBSCRIPTION RATES For One (1) Year in Ellis, Tarant, Dallas, Kaufman. Henderson. Navarro, Hill and Johnson Counties.. $5.00 Six Months $3.00 For One Year Elsewhere $6.00 Six Months $3.50 Single Copies 15c Winner of the 1963 Elijah Parish Lovejoy Award for Courage in Journalism. ASSOCIATION Dallas Papers And Truth The greatest sin a newspaper can commit is to lie to its readers. Printing the truth is the way newspapers and newsmen pay for their right to freedom of the press granted in the first amendment to the Constituton of the United States. An untruth was deliberately printed in the Sheriff Bill. Decker, Man of the Year, story of SUNDAY MAGAZINE by Bill Morgan in the Dallas Times Herald of January _7, 1968. On page 10 of the magazine, Morgan wrote about Sheriff Bill Decker: In late November, with a force of 300-plus under full strength, Decker turned down the application of a police officer who had 11 V2 years service. "Re had a good record," Decker said. "But lie failed to carry out a rule of his department and he was dismissed. -

Communications

Crisis Communications 1 2 1 3 2 4 3 5 4 6 5 7 6 In short, do your values match the generally held values of the public? Which public? 8 7 9 8 10 9 11 1 0 12 1 1 13 1 2 Sudden vs. Smoldering Crisis SUDDEN 28.53% SMOLDERING 71.47% 14 2017 Crisis Categories 3.94 % 4.52% 3.67% 5.76% Catastrophes 4.52% 10.94% Class Action Lawsuits 3.67% 4.47% Consumerism/Activism 5.76% 2.86% Cyber Crime 4.47% 6.64% Defects and Recalls 2.86% Discrimination 18.01% Environmental Damage 4.52% 18.01% Executive Dismissal 4.18% 26.73% Labor Disputes 3.77% Mismanagement 26.73% Whistleblowing 6.64% White Collar Crime 10.94% Other 3.94% 4.52% 3.77% 4.18% 15 2017 Crisis Categories CATEGORY 2017% 2016% CATEGORY 2017% 2016% Catastrophes 4.12% 0.17% Financial Damage 0.11% 0.14% Casualty Accidents 1.61% 0.02% Hostile Takeovers 1.28% 0.14% Class Actions 3.67% 3.93% Labor Disputes 3.77% 0.15% Activism 5.76% 6.83% Mismanagement 26.73% 30.93% Cyber 4.47% 5.24% Sexual Harrassment 0.70% 0.51% Defects/Recalls 2.86% 3.17% Whistlesblowers 6.64% 6.60% Discrimination 18.01% 21.84% White Collar Crime 10.94% 11.07% Envrnmtl Damage 4.52% 2.66% Workplace Violence 0.24% 0.32% Exec Dismissals 4.18% 3.66% 16 28% 17 2 1 18 2 2 19 2 3 • FaceBook (2.23 billion users) • Instagram • Linked In • Twitter 20 2 4 2 4 21 2 5 22 2 6 23 2 7 24 2 8 25 2 9 26 3 0 27 3 1 28 3 2 29 3 3 30 3 4 31 3 5 32 3 6 33 3 7 34 3 8 35 3 9 36 4 0 37 4 1 38 4 2 39 4 3 40 4 4 41 4 5 – Website – Livestream – Voicemail 42 4 6 43 4 7 INTRODUCTION While Buckner is dedicated to safe, responsible operations and the highest standards for those we serve, nothing will test our public reputation more than our behavior during a crisis. -

Broadcasting the BUSINESS WEEKLY of TELEVISION and RADIO

May4,1970:0ur39thYea r:50Ç my Broadcasting THE BUSINESS WEEKLY OF TELEVISION AND RADIO Is CATV destined for ad- supported network? p23 There may be some relief in AT &T radio rates. p38 House committee puts strong reins on pay -TV. p49 TELESTATUS: Where UHF penetrates deepest. p57 mmediate seating coast to coast. We've already sold Cat Ballou, Suddenly Last La. KLFY -TV, Las Vegas KLAS -TV, Grand Summer, Doctor Strangelove, Murderer's Rapids WOOD -TV, Topeka KTSB, Tulsa Row, Alvarez Kelly and a group of other fine KOTV, Syracuse WSYR -TV, St. Louis KTVI, features from our POST'60 FEATURE FILM Birmingham WAPI -TV, Harrisburg WTPA, VOLUME 4 catalog to New York WCBS -TV, Little Rock KARK -TV, Salt Lake City KUTV, Los Angeles KABC -TV, Philadelphia WFIL- Dayton WKEF, Milwaukee WTMJ -TV, Okla- TV, San Francisco KGO -TV, Chicago WBBM- homa City WKY -TV, Peoria WEEK -TV, Jef- TV, Dallas -Ft. Worth KDTV, New Haven ferson City, Mo. KRCG -TV, Lexington WNHC -TV, Indianapolis WISH -TV, Hous- WLEX -TV, Omaha KETV. ton KHOU -TV, Denver KLZ -TV, Albany But, there are still plenty of seats up WAST, New Orleans WVUE, Louisville front. SCREEN GEMS WLKY-TV, Honolulu KGMB -TV, Lafayette, The 1970 Peabod Award forTY news goes to Frank Reynolds. "Frank Reynolds, after a career of many years as a hard -core newsman and reporter, became, in 1968, an anchorman of ABC lEveningNews, which he shares five nights each week wi th his dstinguished colleague, Howard K. Smith. Ti lus a fnsh and engaging personality has emerged as a ger';.uine najor- leaguer. -

President - Briefing Papers by Ron Nessen (3)” of the Ron Nessen Papers at the Gerald R

The original documents are located in Box 18, folder “President - Briefing Papers by Ron Nessen (3)” of the Ron Nessen Papers at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. Copyright Notice The copyright law of the United States (Title 17, United States Code) governs the making of photocopies or other reproductions of copyrighted material. Ron Nessen donated to the United States of America his copyrights in all of his unpublished writings in National Archives collections. Works prepared by U.S. Government employees as part of their official duties are in the public domain. The copyrights to materials written by other individuals or organizations are presumed to remain with them. If you think any of the information displayed in the PDF is subject to a valid copyright claim, please contact the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. ~. THE WHITE HOUSE WASHINGTON MEETING WITH THO~L~S VAIL ' < ... ·~ ' \' ., '\ Wednesday, August 27, 1975 ., ', "\ 12:45 p.m. (15 minutes) ''· The Oval Office FROM: RON NESSEN I. PURPOSE To give Thomas Vail, Publisher, The Cleveland Plain Dealer, who is generally sympathetic to Republican policies and candidates, an opportunity for a courtesy call. II. BACKGROUND, PARTICIPANTS, PRESS PLAN A. Background: Thomas Vail has been anxious for sometime to have an opportunity to make a courtesy call on you to discuss some issues on his mind and to generally size you up in person. He originally was scheduled to fly with you on Air Force One from Cincinnati to Cleveland during your recent visit but was not able to keep this appointment. Senator Taft, Jim Lynn, Bill Greener and Jerry Warren have all recommended this meeting with Vail.