Dangerous Speech and Social Media Uncharted Strategies for Mitigating Harm Online

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2020

Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2020 Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2020 Nic Newman with Richard Fletcher, Anne Schulz, Simge Andı, and Rasmus Kleis Nielsen Supported by Surveyed by © Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism / Digital News Report 2020 4 Contents Foreword by Rasmus Kleis Nielsen 5 3.15 Netherlands 76 Methodology 6 3.16 Norway 77 Authorship and Research Acknowledgements 7 3.17 Poland 78 3.18 Portugal 79 SECTION 1 3.19 Romania 80 Executive Summary and Key Findings by Nic Newman 9 3.20 Slovakia 81 3.21 Spain 82 SECTION 2 3.22 Sweden 83 Further Analysis and International Comparison 33 3.23 Switzerland 84 2.1 How and Why People are Paying for Online News 34 3.24 Turkey 85 2.2 The Resurgence and Importance of Email Newsletters 38 AMERICAS 2.3 How Do People Want the Media to Cover Politics? 42 3.25 United States 88 2.4 Global Turmoil in the Neighbourhood: 3.26 Argentina 89 Problems Mount for Regional and Local News 47 3.27 Brazil 90 2.5 How People Access News about Climate Change 52 3.28 Canada 91 3.29 Chile 92 SECTION 3 3.30 Mexico 93 Country and Market Data 59 ASIA PACIFIC EUROPE 3.31 Australia 96 3.01 United Kingdom 62 3.32 Hong Kong 97 3.02 Austria 63 3.33 Japan 98 3.03 Belgium 64 3.34 Malaysia 99 3.04 Bulgaria 65 3.35 Philippines 100 3.05 Croatia 66 3.36 Singapore 101 3.06 Czech Republic 67 3.37 South Korea 102 3.07 Denmark 68 3.38 Taiwan 103 3.08 Finland 69 AFRICA 3.09 France 70 3.39 Kenya 106 3.10 Germany 71 3.40 South Africa 107 3.11 Greece 72 3.12 Hungary 73 SECTION 4 3.13 Ireland 74 References and Selected Publications 109 3.14 Italy 75 4 / 5 Foreword Professor Rasmus Kleis Nielsen Director, Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism (RISJ) The coronavirus crisis is having a profound impact not just on Our main survey this year covered respondents in 40 markets, our health and our communities, but also on the news media. -

![Consolidated Report]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0742/consolidated-report-310742.webp)

Consolidated Report]

2017 FELLOWSHIP FOR ORGANIZING ENDEAVORS INC. [CONSOLIDATED REPORT] 0 | P a g e Fellowship for Organizing Endeavors (FORGE), Inc. FORGE’s vision1 is essentially empowerment of the marginalized sector towards just and resilient communities. Crucial, therefore, to FORGE’s work is its contribution to the achievement of social justice and community resilience. SOCIAL JUSTICE2 Filipinos hold deep understanding of justice. Such appreciation and understanding can be derived from traditional Filipino words katarungan and karapatan. Katarungan, with a root word tarong, is a Visayan term which means straight, upright, appropriate or correct. For Filipinos, therefore, justice is rectitude, doing the morally right act, being upright, or doing what is appropriate. Given this understanding, the concept of equity is thus, encompassed. Karapatan, on the other hand, comes from the root word dapat, which means fitting, correct, appropriate. For Filipinos, therefore, the concepts of justice and right are intimately related. Differentiated, however, with the word “law,” the Filipino language uses batas, a command word. The distinction presents that the Filipino language “makes a clear distinction between justice and law; and recognizes that what is legal may not always be just.”3 These concepts are aptly captured in Sec. 1, Article XIII of the 1987 Constitution.4 Essentially, the Constitution commands Congress to give highest priority to the enactment of measures that: ● protect and enhance the right of all the people to human dignity, ● reduce social, economic, and political inequalities, and ● remove cultural inequities by equitably diffusing wealth and political power for the common good. Article XIII goes on to specify certain sectors to which Congress must give priority namely, labor, agrarian reform, urban land reform and housing, health system, protection of women, people’s organizations, and protection of human rights. -

20 MAY 2021, Thursday Headline STRATEGIC May 20, 2021 COMMUNICATION & Editorial Date INITIATIVES Column SERVICE Opinion

20 MAY 2021, Thursday Headline STRATEGIC May 20, 2021 COMMUNICATION & Editorial Date INITIATIVES Column SERVICE Opinion Page Feature Article DENR nabs two wildlife traffickers in Bulacan, rescues endangered cockatoos By DENRPublished on May 19, 2021 QUEZON CITY, MAy 19 -- In a spate of wildlife enforcement operations in the past weeks, the Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR) has successfully arrested two individuals who were selling umbrella cockatoos online. DENR Secretary Roy A. Cimatu said the arrest of the suspects is part of the department's renewed commitment to "conserve specific terrestrial and marine areas representative of the Philippine natural and cultural heritage for present and future generations" amid the pandemic. "We will continue to apprehend these illegal wildlife traders whether we have a pandemic or not. This is what the DENR can always assure the public," Cimatu said. He noted that illegal wildlife traders have become more brazen since the pandemic began, but assured that the DENR remains vigilant to protect the biodiversity. DENR’s Environmental Protection and Enforcement Task Force (EPETF) arrested Rendel Santos, 21, and Alvin Santos, 48, for illegal possession and selling of two (2) Umbrella cockatoos (Cacatua alba) at Barangay Pagala in Baliuag, Bulacan last May 2. The DENR-Community Environment and Natural Resources Office (CENRO) in Baliuag, Bulacan said the suspects were not issued a permit to transport the cockatoos. The Umbrella cockatoo is listed under Appendix II of the Convention of International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES), which means that the species is not necessarily now threatened with extinction but that may become so unless trade is closely controlled. -

Digital News Report 2018 Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism / Digital News Report 2018 2 2 / 3

1 Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2018 Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism / Digital News Report 2018 2 2 / 3 Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2018 Nic Newman with Richard Fletcher, Antonis Kalogeropoulos, David A. L. Levy and Rasmus Kleis Nielsen Supported by Surveyed by © Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism / Digital News Report 2018 4 Contents Foreword by David A. L. Levy 5 3.12 Hungary 84 Methodology 6 3.13 Ireland 86 Authorship and Research Acknowledgements 7 3.14 Italy 88 3.15 Netherlands 90 SECTION 1 3.16 Norway 92 Executive Summary and Key Findings by Nic Newman 8 3.17 Poland 94 3.18 Portugal 96 SECTION 2 3.19 Romania 98 Further Analysis and International Comparison 32 3.20 Slovakia 100 2.1 The Impact of Greater News Literacy 34 3.21 Spain 102 2.2 Misinformation and Disinformation Unpacked 38 3.22 Sweden 104 2.3 Which Brands do we Trust and Why? 42 3.23 Switzerland 106 2.4 Who Uses Alternative and Partisan News Brands? 45 3.24 Turkey 108 2.5 Donations & Crowdfunding: an Emerging Opportunity? 49 Americas 2.6 The Rise of Messaging Apps for News 52 3.25 United States 112 2.7 Podcasts and New Audio Strategies 55 3.26 Argentina 114 3.27 Brazil 116 SECTION 3 3.28 Canada 118 Analysis by Country 58 3.29 Chile 120 Europe 3.30 Mexico 122 3.01 United Kingdom 62 Asia Pacific 3.02 Austria 64 3.31 Australia 126 3.03 Belgium 66 3.32 Hong Kong 128 3.04 Bulgaria 68 3.33 Japan 130 3.05 Croatia 70 3.34 Malaysia 132 3.06 Czech Republic 72 3.35 Singapore 134 3.07 Denmark 74 3.36 South Korea 136 3.08 Finland 76 3.37 Taiwan 138 3.09 France 78 3.10 Germany 80 SECTION 4 3.11 Greece 82 Postscript and Further Reading 140 4 / 5 Foreword Dr David A. -

Marine Litter Legislation: a Toolkit for Policymakers

Marine Litter Legislation: A Toolkit for Policymakers The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the United Nations Environment Programme. No use of this publication may be made for resale or any other commercial purpose whatsoever without prior permission in writing from the United Nations Environment Programme. Applications for such permission, with a statement of the purpose and extent of the reproduction, should be addressed to the Director, DCPI, UNEP, P.O. Box 30552, Nairobi, Kenya. Acknowledgments This report was developed by the Environmental Law Institute (ELI) for the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP). It was researched, drafted, and produced by Carl Bruch, Kathryn Mengerink, Elana Harrison, Davonne Flanagan, Isabel Carey, Thomas Casey, Meggan Davis, Elizabeth Hessami, Joyce Lombardi, Norka Michel- en, Colin Parts, Lucas Rhodes, Nikita West, and Sofia Yazykova. Within UNEP, Heidi Savelli, Arnold Kreilhuber, and Petter Malvik oversaw the development of the report. The authors express their appreciation to the peer reviewers, including Catherine Ayres, Patricia Beneke, Angela Howe, Ileana Lopez, Lara Ognibene, David Vander Zwaag, and Judith Wehrli. Cover photo: Plastics floating in the ocean The views expressed in this report do not necessarily reflect those of the United Nations Environment Programme. © 2016. United Nations Environment Programme. Marine Litter Legislation: A Toolkit for Policymakers Contents Foreword .................................................................................................. -

3 — February 7, 2019

Pahayagan ng Partido Komunista ng Pilipinas ANG Pinapatnubayan ng Marxismo-Leninismo-Maoismo Vol. L No. 3 February 7, 2019 www.philippinerevolution.info EDITORIAL NPA-NEMR mounts Justice for all victims 6 counter-attacks of the US-Duterte fascist THE NEW PEOPLE'S Army (NPA) in Northeast Mindanao frustrated the fascist troops of the Armed regime Forces of the Philippines (AFP) which have been on a 25-day rampage in Agusan del Sur and he revolutionary forces hold the US-Duterte fascist regime Surigao del Sur. The said operati- fully responsible for the brazen murder of NDFP peace on was the AFP's reaction to two consultant Randy Felix Malayao last January 30. Malayao's successful tactical offensives of Tmurder follows public pronouncements by Duterte himself just a the NPA in the last quarter of month ago endorsing mass killings and ordering his death squads to 2018. The relentless military carry out the liquidation of revolutionary forces and supporters of operations were accompanied by the Party and revolutionary movement. aerial bombing and strafing by the Malayao's murder signals the activists as well as all other oppo- Philippine Air Force. escalation of state terrorism and sition forces. According to Ka Maria Mala- armed suppression against activis- Frustrated over its continuing ya, spokesperson of the National ts who are at the forefront of the failure to defeat the revolutionary Democratic Front of the Philippi- broad united opposition against armed movement, the Duterte re- nes (NDFP)-Northeast Mindanao Duterte's tyranny. Malayao is the gime has vented its fascist ire Region, the NPA mounted six co- first high-profile national perso- against the legal democratic for- unter attacks against 4th ID tro- nality killed by state security for- ces employing assassination squ- ops operating in the communities ces after many years. -

The Philippine Center for Investigative Journalism

Social Ethics Society Journal of Applied Philosophy Special Issue, December 2018, pp. 181-206 The Philippine Center for Investigative Journalism (PCIJ) and ABS-CBN through the Prisms of Herman and Chomsky’s “Propaganda Model”: Duterte’s Tirade against the Media and vice versa Menelito P. Mansueto Colegio de San Juan de Letran [email protected] Jeresa May C. Ochave Ateneo de Davao University [email protected] Abstract This paper is an attempt to localize Herman and Chomsky’s analysis of the commercial media and use this concept to fit in the Philippine media climate. Through the propaganda model, they introduced the five interrelated media filters which made possible the “manufacture of consent.” By consent, Herman and Chomsky meant that the mass communication media can be a powerful tool to manufacture ideology and to influence a wider public to believe in a capitalistic propaganda. Thus, they call their theory the “propaganda model” referring to the capitalist media structure and its underlying political function. Herman and Chomsky’s analysis has been centered upon the US media, however, they also believed that the model is also true in other parts of the world as the media conglomeration is also found all around the globe. In the Philippines, media conglomeration is not an alien concept especially in the presence of a giant media outlet, such as, ABS-CBN. In this essay, the authors claim that the propaganda model is also observed even in the less obvious corporate media in the country, disguised as an independent media entity but like a chameleon, it © 2018 Menelito P. -

Appendix .Pdf

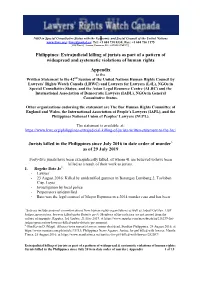

NGO in Special Consultative Status with the Economic and Social Council of the United Nations www.lrwc.org; [email protected]; Tel: +1 604 738 0338; Fax: +1 604 736 1175 3220 West 13th Avenue, Vancouver, B.C. CANADA V6K 2V5 Philippines: Extrajudicial killing of jurists as part of a pattern of widespread and systematic violations of human rights Appendix to the Written Statement to the 42nd Session of the United Nations Human Rights Council by Lawyers’ Rights Watch Canada (LRWC) and Lawyers for Lawyers (L4L), NGOs in Special Consultative Status; and the Asian Legal Resource Centre (ALRC) and the International Association of Democratic Lawyers (IADL), NGOs in General Consultative Status. Other organizations endorsing the statement are The Bar Human Rights Committee of England and Wales, the International Association of People’s Lawyers (IAPL), and the Philippines National Union of Peoples’ Lawyers (NUPL). The statement is available at: https://www.lrwc.org/philippines-extrajudicial-killing-of-jurists-written-statement-to-the-hrc/ __________________________________________________________________________ Jurists killed in the Philippines since July 2016 in date order of murder1 as of 29 July 2019 Forty-five jurists have been extrajudicially killed, of whom 41 are believed to have been killed as a result of their work as jurists. 1. Rogelio Bato Jr2 - Lawyer - 23 August 2016: Killed by unidentified gunmen in Barangay Lumbang 2, Tacloban City, Leyte - Investigation by local police - Perpetrators unidentified - Bato was the legal counsel of Mayor Espinosa in a 2014 murder case and has been 1 Sources include personal communications from human rights organizations as well as Jodesz Gavilan. -

(LGBT) in Brazil: a Spatial Analysis

DOI: 10.1590/1413-81232020255.33672019 1709 A Homicídios da População de Lésbicas, Gays, Bissexuais, Travestis, rt I G Transexuais ou Transgêneros (LGBT) no Brasil: A O uma Análise Espacial rt IC Homicide of Lesbians, Gays, Bisexuals, Travestis, Transexuals, and LE Transgender people (LGBT) in Brazil: a Spatial Analysis Wallace Góes Mendes (https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7852-7334) 1 Cosme Marcelo Furtado Passos da Silva (https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7789-1671) 1 Abstract Violence against LGBT people has Resumo A violência contra Lésbicas, Gays, Bis- always been present in our society. Brazil is the sexuais, Travestis, Transexuais ou Transgêneros country with the highest number of lethal cri- (LGBT) sempre foi presente em nossa sociedade, mes against LGBT people in the world. The aim sendo o Brasil “o país que mais registra crimes le- of this study was to describe the characteristics of tais contra essa população no mundo”. O objetivo homicides of LGBT people in Brazil using spatial foi descrever as características dos homicídios de analysis. The LGBT homicide rate was used to fa- LGBT ocorridos no Brasil por meio de uma aná- cilitate the visualization of the geographical dis- lise espacial. Utilizou-se a taxa de homicídios de tribution of homicides. Public thoroughfares and LGBT para facilitar a visualização da distribuição the victim’s home were the most common places geográfica dos homicídios. As vias públicas e as re- of occurrence. The most commonly used methods sidências das vítimas são os lugares mais comuns for killing male homosexuals and transgender pe- das ocorrências dos crimes. As armas brancas são ople were cold weapons and firearms, respectively; as mais usadas no acometimento contra homosse- however, homicides frequently involved beatings, xuais masculinos e as armas de fogo para trans- suffocation, and other cruelties. -

Pablo Picasso Perhaps a Closer Examination of What the Renowned

1 Chapter 1 INTRODUCTION “Everything you can imagine is real”- Pablo Picasso Perhaps a closer examination of what the renowned painter actually means is that if a human being can imagine something in the scope of the natural laws of reality and physics, then it exists. This rings true for visual art. Whatever a person can conjure in his mind, whether a creature of imagination or an event, the fact that he thought about it means it exists in the realm of reality—not necessarily the realm of physical reality but in the realm of cognitive and mental reality. Pablo Picasso’s quote has been proven by the dominance of visual culture at the present. Today, fascination and enhancement of what people can do and what people can appreciate in the visual realm has seen a significant rise among the people of this generation. With the rise of virtual reality and the Internet in the West, combined with the global popularity of television, videotape and film, this trend seems set to continue (Mirzoeff 1999). In a book titled An Introduction to Visual Culture by Nicholas Mirzoeff, he explained that visual culture, very different from it’s status today, suffered hostility in the West: “a hostility to visual culture in Western thought, originating in the philosophy of Plato. Plato believed that the objects encountered in everyday life, including people, are simply bad copies of the perfect ideal of those objects” (1999, 9). Plato had the idea that what artists do are mere copies of the original, which makes it lose significance because copying what already exists, for Plato, is pointless: 2 In other words, everything we see in the “real” world is already a copy. -

Exploring Networks and Communities: a Case Study of the Supporters and Critics Facebook Pages of the Philippine President

PEOPLE: International Journal of Social Sciences ISSN 2454-5899 Tamanal & Lim, 2019 Volume 4 Issue 3, pp.1485-1502 Date of Publication: 4th February, 2019 DOI-https://dx.doi.org/10.20319/pijss.2019.43.14851502 This paper can be cited as: Tamanal, J. L., & Lim, J. (2019). Exploring Networks and Communities: A Case Study of the Supporters and Critics Facebook Pages of the Philippine President. PEOPLE: International Journal of Social Sciences, 4(3), 1485-1502. This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ or send a letter to Creative Commons, PO Box 1866, Mountain View, CA 94042, USA. EXPLORING NETWORKS AND COMMUNITIES: A CASE STUDY OF THE SUPPORTERS AND CRITICS FACEBOOK PAGES OF THE PHILIPPINE PRESIDENT Juvy Lou Tamanal Department of Media and Communication, Sejong University, Seoul, South Korea [email protected] Jongsoo Lim Department of Media and Communication, Sejong University, Seoul, South Korea [email protected] Abstract This paper provides the current Philippine president’s supporters and critics Facebook pages on social media networks’ description and analyses of their SNSs dataset using NodeXL program. There are three main focuses of the study: (1) implications of the demographic differences of both page networks in terms of age, location and political affiliation, (2) comparative data analyses of the difference in the connected vertices/nodes (e.g., density, diameter, and connected components) of the two opposing networks, and finally, (3) identifying the network actors, the “who” play the roles of the main speakers, mediators and influencers in a social network structure. -

2013 CCG Philippines

Doing Business in the Philippines: 2013 Country Commercial Guide for U.S. Companies INTERNATIONAL COPYRIGHT, U.S. & FOREIGN COMMERCIAL SERVICE AND U.S. DEPARTMENT OF STATE, 2010. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED OUTSIDE OF THE UNITED STATES. • Chapter 1: Doing Business in the Philippines • Chapter 2: Political and Economic Environment • Chapter 3: Selling U.S. Products and Services • Chapter 4: Leading Sectors for U.S. Export and Investment • Chapter 5: Trade Regulations, Customs and Standards • Chapter 6: Investment Climate • Chapter 7: Trade and Project Financing • Chapter 8: Business Travel • Chapter 9: Contacts, Market Research and Trade Events • Chapter 10: Guide to Our Services Return to table of contents Chapter 1: Doing Business In the Philippines • Market Overview • Market Challenges • Market Opportunities • Market Entry Strategy • Market Fact Sheet link Market Overview Return to top Key Economic Indicators and Trade Statistics • The Philippines was one of the strongest economic performers in the region last year, enjoying a 6.6 percent growth rate in 2012, second only to China. That growth continued into the first quarter of 2013, with a 7.8 percent year-on-year increase. The growth rate is projected to stay at about six percent or higher in 2013. • Government and consumer spending fueled the growth. On the production side, the service sector drove the acceleration, with the industrial sector (primarily construction and electricity/gas/water supply) also contributing to growth. Remittances by Overseas Foreign Workers (OFW) continue to be a major economic force in the country’s economy. GDP-per-capita has risen to about $2,600. • The national government’s fiscal deficit ended 2012 at 2.3 percent of GDP, below the programmed 2.6 percent-to-GDP ratio but up from two percent in 2011.