Revision Draft

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Deep-Water Bottom Dropping Page 6 FISHING

Doves usher in a new season * September 12, 2008 Texas’ Premier Outdoor Newspaper Volume 5, Issue 2 * Report on Page 6 www.lonestaroutdoornews.com INSIDE Flyway rivalry prompts HUNTING Texas’ dove research Timing of hunt causes stir among hunters BY CRAIG NYHUS on doves. A team was out two days prior to the hunting season to collect Dove hunters in Texas have long bird specimens for a study compar- feared a federal requirement for the ing the effectiveness of lead and non- use of nonlead shot to pursue their lead shot. But some outfitters and hunters were taken aback by the early Grayson County has become quarry. The state holds the same con- cerns, especially after other states in shooting. famous for its big bucks in the the Central Flyway tried to force Texas Parks and Wildlife biologists state’s lone archery-only Texas to require nonlead shot based are in the first year of a multi-year county. A petition to modify on their waterfowl studies, according study to determine the effectiveness the archery-only rule has many GUNNING FOR RESEARCH: Using volunteer hunters, TPW biologists are to officials. of different load types on wild hunters up in arms. conducting a three-year study of shot effectiveness on dove, but the early That was the genesis of Texas’ own mourning doves using trained Page 7 hunt caused a PR nightmare for officials. Photo by TPW. study on the effect of nonlead shot See DOVE, Page 16 Teal are arriving on schedule along the Texas coast in time for the early season. -

Marine Science

ICES Journal of Marine Science ICES Journal of Marine Science (2015), 72(3), 992–996. doi:10.1093/icesjms/fsu232 Contribution to the Themed Section: ‘Risk Assessment’ Introduction Risk assessment and risk management: a primer for marine scientists Mark T. Gibbs1,2 and Howard I. Browman3* 1Department of Mathematics and Physics, University of Queensland, St Lucia, QLD, Australia 2AECOM 540, Wickham Street, Fortitude Valley, QLD 4007, Australia 3Institute of Marine Research, Marine Ecosystem Acoustics Disciplinary Group, Austevoll Research Station, N-5392 Storebø, Norway *Corresponding author: e-mail: [email protected] Gibbs, M. T., and Browman, H. I. Risk assessment and risk management: a primer for marine scientists. – ICES Journal of Marine Science, 72: 992–996. Received 29 November 2014; accepted 30 November 2014. Risk assessment is the management approach or framework of choice in many disciplines, including health care and research, engineering design, and particularly the insurance sector which relies on the best available forward projections of natural hazards and accidents. The marine manage- ment community, which includes researchers, practitioners, and resource managers responsible for individual targeted stocks, aquaculture activ- ities, and the marine environment in general, has been slower to take up quantitative risk assessment approaches. Whilst there are prominent examples where risk assessment and management approaches have been applied, they are relatively few. This article theme set presents examples of such and identifies tools and approaches that can be applied to coastal and oceanic marine systems worldwide. The methods developed and the lessons learned from these studies can be used to guide researchers, practitioners, and resource managers. -

Revision Draft

MRAG-MSC-F13-v1.1 March 2020 Shark Bay Prawn Managed Fishery Public Certification Report Prepared for the Western Australian Fishing Industry Council Certificate Number: MSC-F-31208 10 December 2020 Conformity Assessment Body MRAG Americas, Inc. (CAB) Richard Banks (TL/P3), Kevin McLoughlin (P1) and Mihaela Zaharia Assessment team (P2) Fishery client Western Australian Fishing Industry Council Assessment Type First Reassessment 1 MRAG Americas – US2733 Shark Bay Prawn Managed Fishery PCR MRAG-MSC-F13-v1.1 March 2020 Document Control Record Document Draft Submitted By Date Reviewed By Date ACDR RB, MZ, KM 8 March 2020 ASP 9 March 2020 CDR/PRDR RB, MZ, KM 8 June 2020 RB 9 June 2020 PCDR RB, MZ,KM 10 July 2020 RB 13 July 2020 ASP 12 August 2020 FRD RB, MZ,KM 29 Sept 2020 RB and ASP 13 Nov 2020 PCR RB, MZ, KM 8 December 2020 EW 9 Dec 2020 2 MRAG Americas – US2733 Shark Bay Prawn Managed Fishery PCR MRAG-MSC-F13-v1.1 March 2020 1 Contents 1 Contents ..................................................................................................................... 3 2 Glossary ..................................................................................................................... 6 3 Executive summary .................................................................................................... 8 4 Report details ........................................................................................................... 10 4.1 Authorship and peer review details .............................................................. -

MARINE FISHERIES REGULATION SUMMARY As of June 1, 2020

MARINE FISHERIES REGULATION SUMMARY as of June 1, 2020 Updated by Jared Silva, Policy Analyst This is not an official copy of the Commonwealth’s marine fishery laws and regulations. The information in this document outlines the general laws and regulations governing recreational and commercial fishing in the waters under the jurisdiction of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts. It is not comprehensive. Although every attempt has been made to keep this document accurate and up to date, this is not an official copy of the Commonwealth’s marine fishery laws and regulations, and should not be consulted as such. The closure maps depicted in this document demonstrate certain specific closures but are not inclusive of all closures that may affect a certain fishing activity. Please review official copies of M.G.L. c. 130 and 322 CMR for full and accurate descriptions of marine fisheries laws and regulations. For comprehensive regulations contact the Secretary of State Division of Publications and Regulations and for the statutory text to M.G.L Ch. 130 visit the Massachusetts Legislature’s website (http://www.malegislature.gov). MASSACHUSETTS DIVISION OF MARINE FISHERIES RULES & REGULATIONS SUMMARY (as of June 1, 2020) Refer to Chapter 130 and 322 CMR for details. TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE FISHERY 3 RECENT REGULATORY CHANGES 7 RECREATIONAL FISHING 8 HOOK AND LINE (includes Rod & Reel) 10 LOBSTERING commercially with Traps in state waters 14 LOBSTERING commercially with Traps - using Student Lobster Permit 18 LOBSTERING commercially with SCUBA in state waters 20 LOBSTERING recreationally with Traps or SCUBA using the Non-Commercial Lobster Permit 23 POTTING for Sea Bass 25 POTTING for Scup 27 POTTING for Whelks 30 FISH WEIRS 31 SINK GILLNETTING (Fishing on or near bottom) 33 SURFACE GILLNETTING (Fishing on or near surface) 35 MOBILE GEAR: Trawls, Scottish/Danish Seines, and Pair Seines – no regulatory fishery endorsements or inshore net 38 MOBILE GEAR: Trawls, Scottish/Danish Seines, and Pair Seines - with small-mesh regulated fishery endorsements. -

The Arran Marine Regeneration Trial

Community of Arran Seabed Trust The Arran Marine Regeneration Trial Development of a Community-Based Marine Protected Area The Proposals February 2005 c/o The Secretary of COAST Claveron Lamlash Isle of Arran KA27 8NB Tele: 01770 600552 email: [email protected] web: www.arrancoast.co.uk “I‟m truly sorry man‟s dominion has broken Nature‟s social union.” Robert Burns 1 CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 3 1. BACKGROUND 5 1.1 Community of Arran Seabed Trust 5 1.2 Arran 6 1.3 Lamlash Bay 7 1.4 Maerl 7 1.5 Context 8 2. OBJECTIVES 9 3. PROGRESS TO DATE 10 3.1 A community lead approach to marine conservation 10 3.1.1. Clauchlands maerl No Take Zone 11 3.1.2 Lamlash Bay Marine Protected area 12 3.1.3 Fisheries regeneration 13 3.2 Baseline Biological Surveys 13 3.2.1 Seasearch 13 3.2.2 University Marine Biological Station Millport 14 3.3. Conservation significance of Lamlash Bay 15 3.3.1 Maerl 16 3.3.2 Sea Grass and wider area 19 3.3.3 Commercial and other species in NTZ and MPA 20 4 BENEFITS TO OTHER USERS 20 4.1 Fisheries 20 4.2 Tourism and associated socio-economic benefits 22 5 ACTION PLAN 22 5.1 Arran Marine Regeneration Trial 22 5.2 Monitoring 22 5.3 Funding 24 6 CONCLUSIONS 24 7 REFERENCES 25 8 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 27 APPENDIX 1 28 APPENDIX 2 ` 29 APPENDIX 3 30 APPENDIX 4 31 APPENDIX 5 1 APPENDIX 6 and APPENDIX 7 3 . -

T Own of Whiting, Maine Comprehensive Plan

T OWN OF WHITING, MAINE The Mill Pond at sunset COMPREHENSIVE PLAN 2018 The Town of Whiting 2018 Comprehensive Plan Prepared by the Whiting Comprehensive Plan Committee: James Burns Kenneth Smith Mary-Alice Look Robert Spencer Consultant: Washington County Council of Governments TABLE OF CONTENTS A - Vision and Executive Summary ________________________________________________________________ 1 Executive Summary _____________________________________________________________________________________ 1 Public Participation Summary ________________________________________________________________________________ 1 Town of Whiting Vision Statement ____________________________________________________________________________ 1 B - History and Archeological Resources ______________________________________________________ 10 Farming _______________________________________________________________________________________________________ 12 Industry _______________________________________________________________________________________________________ 13 Transportation ________________________________________________________________________________________________ 14 Historic Buildings _____________________________________________________________________________________________ 14 Cemeteries ____________________________________________________________________________________________________ 15 Archeological Sites ____________________________________________________________________________________________ 15 C - Population ______________________________________________________________________________________ -

NOAA Grant Number: NA08NMF4540664 (DMR#3312

NOAA Grant Number: NA08NMF4540664 (DMR#3312) Grantee: Maine Department of Marine Resources (ME DMR) Project Title: An Assessment of Sea Scallop Distribution and Abundance in Federal Waters of the Gulf of Maine Project Code: 08-SCA-03 Amount of Grant: Elephant Trunk Access Area: 70,000 lbs. and Days-At-Sea in Open Access Areas: 20 DAS (Research TAC Set Aside Scallop Exemption Program for 2008 Fishing Year) Award Start Date: 7/1/2008 Period Covered by Report: 7/1/2008 – 6/30/2011 Executive Summary The sea scallop fishery in the Northern Gulf of Maine (NGOM) occurs in federal waters and is managed by the New England Fishery Management Council. The NGOM resource and associated fishery are at times locally important but amount to a small portion of the total stock and landings. The fishery is managed by TAC independently of the rest of the EEZ sea scallop stock. The NGOM fishery does not use biological reference points as targets or thresholds. A cooperative survey was carried out by the Maine Department of Marine Resources and the University of Maine in June and July, 2009. Survey results indicate that the biomass of NGOM sea scallops targeted by the fishery (102+ mm or 4+ in shell height) was approximately 80-140 mt of meats during 2009. Landings during 2009 amounted to approximately 7 mt. The exploitation rate (reported landings in weight / estimated biomass) in the NGOM during 2009 was estimated at approximately 0.05 to 0.08. These estimates are based on density estimates from the survey assuming a range of 30-50% in dredge capture efficiency. -

Fish Fillets Atlantic Cod

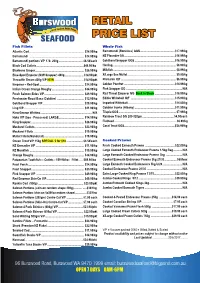

Fish Fillets Whole Fish Atlantic Cod ........................................................................ $24.90/kg Barramundi (Boneless) GGS ............................................. $17.99/kg Barramundi ....................................................................... $24.90/kg NZ Flounder GG .................................................................. $16.99/kg Barramundi portions V/P 170- 200g ............................... $6.50/each Goldband Snapper GGS .................................................... $16.99/kg Black Cod Cutlets..............................................................$49.90/kg Herring ................................................................................... $6.90/kg Bluebone Groper................................................................ $26.90/kg Milkfish .................................................................................. $8.99/kg Blue-Spot Emperor (N/W Snapper) 400g ........................ $14.90/pkt X/Large Sea Mullet ............................................................... $9.90/kg Threadfin Bream 400g V/P NEW ...................................... $14.90/pkt Pilchards IQF ........................................................................ $6.99/kg Emperor – Red-Spot .......................................................... $24.90/kg Golden Pomfret .................................................................. $14.99/kg Indian Ocean Orange Roughy .......................................... $34.90/kg Pink Snapper GG ........................................................................ -

Fisheries Victoria Assessment Report Series No

Victorian King George Whiting Bay and Inlet Stock Assessment 2010 Kemp J, Ryan KL, Brown L, Bruce TK, MacDonald M & Conron S May 2012 Fisheries Victoria Assessment Report Series No. 65 King George Whiting 2010 If you would like to receive this Author Contact Details: Dr. Jodie Kemp information/publication in an Fisheries Research Branch accessible format (such as large PO Box 114, Queenscliff, Victoria 3223 print or audio) please call the Authorised by the Victorian Government, Customer Service Centre on: 1 Spring Street, Melbourne 136 186, TTY: 1800 122 969, Printed by the Fisheries Research Branch, or email Victoria [email protected] Published by the Department of Primary Industries © The State of Victoria, Department of Primary Industries, 2012. Copies are available from the website: www.dpi.vic.gov.au/fishing This publication is copyright. No part may be reproduced by any process except in accordance General disclaimer with the provisions of the Copyright Act 1968. This publication may be of assistance to you but the State of Victoria and its employees do not Preferred way to cite this publication: guarantee that the publication is without flaw of Kemp J, Ryan KL, Brown L, Bruce TK, any kind or is wholly appropriate for your MacDonald, M Conron S (2012). Victorian King particular purposes and therefore disclaims all George Whiting Bay and Inlet Stock Assessment liability for any error, loss or other consequence 2010. Fisheries Victoria Assessment Report Series which may arise from you relying on any No. 65. information in this publication. ISSN 1329‐7287 ISBN 978‐1‐74326‐174‐3 (print) King George Whiting 2010 ii Executive Summary low. -

This Comprehensive Guide to Fishing on Kangaroo Island Has Been Kindly Supplied by Shane Mensforth, Editor of SA Angler Magazine

1 This comprehensive guide to fishing on Kangaroo Island has been kindly supplied by Shane Mensforth, Editor of SA Angler Magazine www.saangler.com.au KINGSCOTE/BAY OF SHOALS Kingscote, the Island’s “capital”, is situated between the Bay of Shoals and Nepean Bay and offers a good choice of boat, jetty and shore fishing. A long sand spit extends in an easterly direction some 5km from the western side of the Bay of Shoals. The waters on the south side of the spit provide good fishing for whiting, gar, salmon trout and big sand crabs. A deep channel runs along the southern side and is easily accessed from the boat ramp. Whiting hug the edges of the channel, along with good numbers of plump salmon trout which are great sport on trolled lures and light tackle. Tides run strongly through the channels, so sinker weight should be changed accordingly. Garfish are most common over the weed beds directly east of the boat ramp and these can be caught on light gear or dabbed at night with the aid of a spotlight and long handled net. Large sand crabs — considered by most to be the equal of blue swimmers to eat — can be drop netted over the Bay of Shoals sand patches or near the channel markers east of the boat ramp. At the eastern end of the spit are the north and south beacons that indicate the width of the spit at this point. Whiting can be caught in good numbers between the beacons in either the deeper areas or on the sandy patches in the shallows. -

Scottish Sanitary Survey Project

Scottish Sanitary Survey Project Sanitary Survey Report Arran: Lamlash Bay (NA007) & Arran: Whiting Bay (NA009) July 2010 Cefas SSS F0912 V1.0 20/08/10 Report Distribution – Arran: Lamlash Bay and Arran: Whiting Bay Date Name Agency* Linda Galbraith Scottish Government Mike Watson Scottish Government Ewan Gillespie SEPA Douglas Sinclair SEPA Sarah Gillman Scottish Water Alex Adrian Crown Estate Andrew Miller North Ayrshire Council William Murray North Ayrshire Council Billy Currie Harvester Hector Stewart Harvester * Distribution of both draft and final reports to relevant agency personnel is undertaken by FSAS. ** Distribution of draft and final reports to harvesters in undertaken by the relevant local authority. ii Cefas SSS F0912 V1.0 20/08/10 Table of Contents 1. General Description .................................................................................. 1 2. Fishery ...................................................................................................... 2 3. Human Population .................................................................................... 4 4. Sewage Discharges .................................................................................. 6 5. Geology and Soils ................................................................................... 13 6. Land Cover ............................................................................................. 15 7. Farm Animals .......................................................................................... 17 8. Wildlife ................................................................................................... -

Framework 23); and 4) New Management Measures Required in FW22 and FW23 That Reduce Impacts on Sea Turtles

DRAFT 1.0 AFFECTED ENVIRONMENT 1.1 ATLANTIC SEA SCALLOP RESOURCE The Atlantic sea scallop (Placopetcen magellanicus) is a bivalve mollusk that is distributed along the continental shelf, typically on sand and gravel bottoms from the Gulf of St. Lawrence to North Carolina (Hart and Chute, 2004). The species generally inhabit waters less than 20o C and depths that range from 30-110 m on Georges Bank, 20-80 m in the Mid-Atlantic, and less than 40 m in the near-shore waters of the Gulf of Maine. Although all sea scallops in the US EEZ are managed as a single stock per Amendment 10, assessments focus on two main parts of the stock and fishery that contain the largest concentrations of sea scallops: Georges Bank and the Mid-Atlantic, which are combined to evaluate the status of the whole stock. The scallop assessment is a very data rich assessment. The overall biomass and recruitment information are based on results from several surveys including: the NEFSC federal survey; SMAST video survey; VIMS paired tow dredge survey; and towed camera survey conducted by Arnie’s Fishery. These data sources are combined in the assessment of the resource and in models used by the Scallop PDT to set fishery allocations. 1.1.1 Benchmark Assessment The sea scallop resource just had a benchmark assessment in 2014 (SARC59, 2014). Therefore, all of the data and models used to assess the stock were reviewed. The final results from that assessment have been incorporated into this action, including updated reference points for status determination (See Section ???).