Grant Morrison Interview

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Myth, Metatext, Continuity and Cataclysm in Dc Comics’ Crisis on Infinite Earths

WORLDS WILL LIVE, WORLDS WILL DIE: MYTH, METATEXT, CONTINUITY AND CATACLYSM IN DC COMICS’ CRISIS ON INFINITE EARTHS Adam C. Murdough A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS August 2006 Committee: Angela Nelson, Advisor Marilyn Motz Jeremy Wallach ii ABSTRACT Angela Nelson, Advisor In 1985-86, DC Comics launched an extensive campaign to revamp and revise its most important superhero characters for a new era. In many cases, this involved streamlining, retouching, or completely overhauling the characters’ fictional back-stories, while similarly renovating the shared fictional context in which their adventures take place, “the DC Universe.” To accomplish this act of revisionist history, DC resorted to a text-based performative gesture, Crisis on Infinite Earths. This thesis analyzes the impact of this singular text and the phenomena it inspired on the comic-book industry and the DC Comics fan community. The first chapter explains the nature and importance of the convention of “continuity” (i.e., intertextual diegetic storytelling, unfolding progressively over time) in superhero comics, identifying superhero fans’ attachment to continuity as a source of reading pleasure and cultural expressivity as the key factor informing the creation of the Crisis on Infinite Earths text. The second chapter consists of an eschatological reading of the text itself, in which it is argued that Crisis on Infinite Earths combines self-reflexive metafiction with the ideologically inflected symbolic language of apocalypse myth to provide DC Comics fans with a textual "rite of transition," to win their acceptance for DC’s mid-1980s project of self- rehistoricization and renewal. -

741.5 Batman..The Joker

Darwyn Cooke Timm Paul Dini OF..THE FLASH..SUPERBOY Kaley BATMAN..THE JOKER 741.5 GREEN LANTERN..AND THE JUSTICE LEAGUE OF AMERICA! MARCH 2021 - NO. 52 PLUS...KITTENPLUS...DC TV VS. ON CONAN DVD Cuoco Bruce TImm MEANWHILE Marv Wolfman Steve Englehart Marv Wolfman Englehart Wolfman Marshall Rogers. Jim Aparo Dave Cockrum Matt Wagner The Comics & Graphic Novel Bulletin of In celebration of its eighty- queror to the Justice League plus year history, DC has of Detroit to the grim’n’gritty released a slew of compila- throwdowns of the last two tions covering their iconic decades, the Justice League characters in all their mani- has been through it. So has festations. 80 Years of the the Green Lantern, whether Fastest Man Alive focuses in the guise of Alan Scott, The company’s name was Na- on the career of that Flash Hal Jordan, Guy Gardner or the futuristic Legion of Super- tional Periodical Publications, whose 1958 debut began any of the thousands of other heroes and the contemporary but the readers knew it as DC. the Silver Age of Comics. members of the Green Lan- Teen Titans. There’s not one But it also includes stories tern Corps. Space opera, badly drawn story in this Cele- Named after its breakout title featuring his Golden Age streetwise relevance, emo- Detective Comics, DC created predecessor, whose appear- tional epics—all these and bration of 75 Years. Not many the American comics industry ance in “The Flash of Two more fill the pages of 80 villains become as iconic as when it introduced Superman Worlds” (right) initiated the Years of the Emerald Knight. -

2020 Chain Bridge District Life to Eagle Guidelines

2020 CHAIN BRIDGE DISTRICT LIFE TO EAGLE GUIDELINES 2020 Edition: This edition of the CBD Life to Eagle Guidelines reflects relevant BSA policies and publications in effect as of January 15, 2020. It also contains explanations, interpretive information and suggestions intended to help Scouts avoid common errors that could delay their progress along the path to Eagle rank. Because BSA policies can change, Scouts should work closely with a Unit Eagle Advisor who will be knowledgeable concerning future policy changes that could affect the Life-to-Eagle process. On February 1, 2019, BSA started admitting girls to "Scouts BSA". Advancement requirements for girls are the same as for boys, but there are some "Temporary Transition Rules" for new Scouts (boys and girls) who joined Scouts BSA for the first time in 2019. The Temporary Transition Rules are not available for new Scouts BSA members who joined after December 31, 2019. Many Scouters support the Life to Eagle process in the Chain Bridge District. Special recognition is given to: Richard Meyers, Chain Bridge District Eagle Chair The Chain Bridge District Eagle Board Eagle Advisers and Project Coaches in CBD troops, crews, and ship These dedicated adult leaders contribute their valuable time and patient assistance to help Life Scouts attain the highest rank in Scouting. Charge to the Eagle Scout I charge you to undertake your citizenship with a solemn dedication. Be a leader, but only toward the best. Lift up every task you do and every office. You hold to the high level of service to God and your fellow man. -

Superman Unchained: the New 52 Free

FREE SUPERMAN UNCHAINED: THE NEW 52 PDF Scott Snyder,Jim Lee | 240 pages | 14 Jan 2015 | DC Comics | 9781401245221 | English | United States The New 52 - Wikipedia Uh-oh, it looks like your Internet Explorer is out of date. For a better shopping experience, please upgrade now. Javascript is not enabled in your browser. Enabling JavaScript in your browser will allow you to experience all the features of our site. Learn how to enable JavaScript on your browser. Home 1 Books 2. Add to Wishlist. Sign in to Purchase Instantly. Members save with free shipping everyday! See details. Overview Decades before the Last Son of Krypton became Earth's champion, another being of incredible power fell from the sky. His role in humanity's deadliest conflict became America's darkest secret. Now the secret is out. And this super soldier has been unchained once more. The Man of Steel. His arch-enemy, Lex Luthor. His close confidant, Lois Lane. Her Superman Unchained: The New 52 father, General Sam Lane. Techno-terrorists with a Superman Unchained: The New 52 link to the past. All of them will vie for control of this hidden engine of destruction. Product Details About the Author. About the Author. He is a dedicated and un-ironic fan of Elvis Presley. Related Searches. View Product. In this final team-up issue, all-out war has broken out in the streets of Shamba-La! The worlds of Batman and the legendary vigilante the Shadow collide in this crossover for The worlds of Batman and the legendary vigilante the Shadow collide in this crossover for the ages, now available in paperback! From the incredible minds of iconic authors Scott Snyder and Steve Orlando comes the resurgence of a classic noir character. -

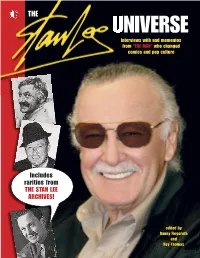

Includes Rarities from the STAN LEE ARCHIVES!

THE UNIVERSE Interviews with and mementos from “THE MAN” who changed comics and pop culture Includes rarities from THE STAN LEE ARCHIVES! edited by Danny Fingeroth and Roy Thomas CONTENTS About the material that makes up THE STAN LEE UNIVERSE Some of this book’s contents originally appeared in TwoMorrows’ Write Now! #18 and Alter Ego #74, as well as various other sources. This material has been redesigned and much of it is accompanied by different illustrations than when it first appeared. Some material is from Roy Thomas’s personal archives. Some was created especially for this book. Approximately one-third of the material in the SLU was found by Danny Fingeroth in June 2010 at the Stan Lee Collection (aka “ The Stan Lee Archives ”) of the American Heritage Center at the University of Wyoming in Laramie, and is material that has rarely, if ever, been seen by the general public. The transcriptions—done especially for this book—of audiotapes of 1960s radio programs featuring Stan with other notable personalities, should be of special interest to fans and scholars alike. INTRODUCTION A COMEBACK FOR COMIC BOOKS by Danny Fingeroth and Roy Thomas, editors ..................................5 1966 MidWest Magazine article by Roger Ebert ............71 CUB SCOUTS STRIP RATES EAGLE AWARD LEGEND MEETS LEGEND 1957 interview with Stan Lee and Joe Maneely, Stan interviewed in 1969 by Jud Hurd of from Editor & Publisher magazine, by James L. Collings ................7 Cartoonist PROfiles magazine ............................................................77 -

Please Continue on Back If Needed!

DARK HORSE DC: VERTIGO MARVEL CONT. ANGEL AMERICAN VAMPIRE DEADPOOL BPRD ASTRO CITY FANTASTIC FOUR BUFFY FABLES GHOST RIDER CONAN THE BARBARIAN FAIREST GUARDIANS OF THE GALAXY HELLBOY FBP HAWKEYE MASSIVE SANDMAN INDESTRUCTIBLE HULK "THE" STAR WARS TRILLIUM IRON MAN STAR WARS - Brian Wood Classic UNWRITTEN IRON PATRIOT STAR WARS LEGACY WAKE LOKI STAR WARS DARK TIMES IDW MAGNETO DC COMICS BLACK DYNAMITE MIGHTY AVENGERS ACTION COMICS DOCTOR WHO MIRACLEMAN ADVENTURES OF SUPERMAN G.I. JOE MOON KNIGHT ALL-STAR WESTERN G.I. JOE REAL AMERICAN HERO MS MARVEL ANIMAL MAN G.I. JOE SPECIAL MISSIONS NEW AVENGERS AQUAMAN GHOSTBUSTERS NEW WARRIORS BATGIRL GODZILLA NOVA BATMAN JUDGE DREDD ORIGIN II BATMAN / SUPERMAN MY LITTLE PONY PUNISHER BATMAN / SUPERMAN POWERPUFF GIRLS SAVAGE WOLVERINE BATMAN & ---- SAMURAI JACK SECRET AVENGERS BATMAN 66 STAR TREK SHE HULK BATMAN BEYOND UNIVERSE TEENAGE MNT CLASSICS SILVER SURFER BATMAN LIL GOTHAM TEENAGE MUTANT NINJA TURTLES SUPERIOR FOES OF SPIDERMAN BATMAN: THE DARK KNIGHT TRANSFORMERS More Than Meets Eye SUPERIOR SPIDERMAN BATWING TRANSFORMERS Regeneration One SUPERIOR SPIDERMAN TEAM-UP BATWOMAN TRANSFORMERS Robots in Disguise THOR GOD OF THUNDER BIRDS OF PREY IMAGE THUNDERBOLTS CATWOMAN ALEX & ADA UNCANNY AVENGERS CONSTANTINE BEDLAM UNCANNY X-MEN DETECTIVE COMICS BLACK SCIENCE WOLVERINE EARTH 2 BOUNCE WOLVERINE & THE X-MEN FLASH CHEW X-FORCE GREEN ARROW EAST OF WEST X-MEN GREEN LANTERN ELEPHANTMENT X-MEN LEGACY -

30Th ANNIVERSARY 30Th ANNIVERSARY

July 2019 No.113 COMICS’ BRONZE AGE AND BEYOND! $8.95 ™ Movie 30th ANNIVERSARY ISSUE 7 with special guests MICHAEL USLAN • 7 7 3 SAM HAMM • BILLY DEE WILLIAMS 0 0 8 5 6 1989: DC Comics’ Year of the Bat • DENNY O’NEIL & JERRY ORDWAY’s Batman Adaptation • 2 8 MINDY NEWELL’s Catwoman • GRANT MORRISON & DAVE McKEAN’s Arkham Asylum • 1 Batman TM & © DC Comics. All Rights Reserved. JOEY CAVALIERI & JOE STATON’S Huntress • MAX ALLAN COLLINS’ Batman Newspaper Strip Volume 1, Number 113 July 2019 EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Comics’ Bronze Age and Beyond! Michael Eury TM PUBLISHER John Morrow DESIGNER Rich Fowlks COVER ARTIST José Luis García-López COVER COLORIST Glenn Whitmore COVER DESIGNER Michael Kronenberg PROOFREADER Rob Smentek IN MEMORIAM: Norm Breyfogle . 2 SPECIAL THANKS BACK SEAT DRIVER: Editorial by Michael Eury . 3 Karen Berger Arthur Nowrot Keith Birdsong Dennis O’Neil OFF MY CHEST: Guest column by Michael Uslan . 4 Brian Bolland Jerry Ordway It’s the 40th anniversary of the Batman movie that’s turning 30?? Dr. Uslan explains Marc Buxton Jon Pinto Greg Carpenter Janina Scarlet INTERVIEW: Michael Uslan, The Boy Who Loved Batman . 6 Dewey Cassell Jim Starlin A look back at Batman’s path to a multiplex near you Michał Chudolinski Joe Staton Max Allan Collins Joe Stuber INTERVIEW: Sam Hamm, The Man Who Made Bruce Wayne Sane . 11 DC Comics John Trumbull A candid conversation with the Batman screenwriter-turned-comic scribe Kevin Dooley Michael Uslan Mike Gold Warner Bros. INTERVIEW: Billy Dee Williams, The Man Who Would be Two-Face . -

DC Event Timeline

Serie Titel No. Enthält US Hefte Crisis on Infinite Earth / Zero Hour JLA Sonderband (Dino) Crisis on Infinite Earths I 12 Crisis on Infinite Earths 1‐6 Dino JLA Sonderband (Dino) Crisis on Infinite Earths II 13 Crisis on Infinite Earths 7‐12 Dino Superman (Carlsen) Der Tag an dem Superman starb 1 Adventures of SM 497 / SM Man of Steel 18‐19 / Justice League 69 / Superman 74‐75 Carlsen Superman (Carlsen) Eine Welt ohne Superman I 2 Adventures of SM 498‐499 / Action Comics 685 / SM Man of Steel 20 / Superman 76 Carlsen Superman (Carlsen) Eine Welt ohne Superman II 3 Adventures of SM 500 / Action Comics 686 / SM Man of Steel 21 / Superman 77 Carlsen Superman (Carlsen) Supermans Rückkehr I 4 Adventures of SM 501 / Action Comics 687‐688 / SM Man of Steel 22 / Superman 78 Carlsen Superman (Carlsen) Supermans Rückkehr II 5 Action Comics 689 / SM Man of Steel 23‐24 / Superman 79 / Adventures of SM 502 Carlsen Superman (Carlsen) Supermans Rückkehr III 6 SM Man of Steel 25 / Superman 80‐81 / Adventures of SM 503 / Action Comics 690 Carlsen Superman (Carlsen) Supermans Rückkehr IV 7 Action Comics 691 / SM Man of Steel 26 / Green Lantern 46 / Superman 82 / Adventures of SM 504 Carlsen JLA Special Green Lantern: Emerald Twilight 1 Green Lantern 48‐50 Dino Superman (Carlsen) Superman/Doomsday: Hunter/Prey 1‐3 8 Superman/Doomsday: Hunter/Prey 1‐3 Carlsen JLA Sonderband (Dino) Zero Hour 3 Zero Hour: Crisis in Time 4‐0 Dino Zero Hour Aftermath / Lead-In to Crisis JLA Sonderband (Dino) Underworld 2 Underworld Unleashed 1‐3 Dino JLA Sonderband (Dino) Final -

Transatlantica, 1 | 2010 “How ‘Ya Gonna Keep’Em Down at the Farm Now That They’Ve Seen Paree?”: France

Transatlantica Revue d’études américaines. American Studies Journal 1 | 2010 American Shakespeare / Comic Books “How ‘ya gonna keep’em down at the farm now that they’ve seen Paree?”: France in Super Hero Comics Nicolas Labarre Electronic version URL: https://journals.openedition.org/transatlantica/4943 DOI: 10.4000/transatlantica.4943 ISSN: 1765-2766 Publisher Association française d'Etudes Américaines (AFEA) Electronic reference Nicolas Labarre, ““How ‘ya gonna keep’em down at the farm now that they’ve seen Paree?”: France in Super Hero Comics”, Transatlantica [Online], 1 | 2010, Online since 02 September 2010, connection on 22 September 2021. URL: http://journals.openedition.org/transatlantica/4943 ; DOI: https://doi.org/ 10.4000/transatlantica.4943 This text was automatically generated on 22 September 2021. Transatlantica – Revue d'études américaines est mise à disposition selon les termes de la licence Creative Commons Attribution - Pas d'Utilisation Commerciale - Pas de Modification 4.0 International. “How ‘ya gonna keep’em down at the farm now that they’ve seen Paree?”: France... 1 “How ‘ya gonna keep’em down at the farm now that they’ve seen Paree?”: France in Super Hero Comics Nicolas Labarre 1 Super hero comics are a North-American narrative form. Although their ascendency points towards European ancestors, and although non-American heroes have been sharing their characteristics for a long time, among them Obelix, Diabolik and many manga characters, the cape and costume genre remains firmly grounded in the United States. It is thus unsurprising that, with a brief exception during the Second World War, super hero narratives should have taken place mostly in the United States (although Metropolis, Superman’s headquarter, was notoriously based on Toronto) or in outer space. -

Relationality and Masculinity in Superhero Narratives Kevin Lee Chiat Bachelor of Arts (Communication Studies) with Second Class Honours

i Being a Superhero is Amazing, Everyone Should Try It: Relationality and Masculinity in Superhero Narratives Kevin Lee Chiat Bachelor of Arts (Communication Studies) with Second Class Honours This thesis is presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of The University of Western Australia School of Humanities 2021 ii THESIS DECLARATION I, Kevin Chiat, certify that: This thesis has been substantially accomplished during enrolment in this degree. This thesis does not contain material which has been submitted for the award of any other degree or diploma in my name, in any university or other tertiary institution. In the future, no part of this thesis will be used in a submission in my name, for any other degree or diploma in any university or other tertiary institution without the prior approval of The University of Western Australia and where applicable, any partner institution responsible for the joint-award of this degree. This thesis does not contain any material previously published or written by another person, except where due reference has been made in the text. This thesis does not violate or infringe any copyright, trademark, patent, or other rights whatsoever of any person. This thesis does not contain work that I have published, nor work under review for publication. Signature Date: 17/12/2020 ii iii ABSTRACT Since the development of the superhero genre in the late 1930s it has been a contentious area of cultural discourse, particularly concerning its depictions of gender politics. A major critique of the genre is that it simply represents an adolescent male power fantasy; and presents a world view that valorises masculinist individualism. -

1 in Our Culture, the Decisive Political Conflict, Which Governs Every

THE GRAPHIC NOVEL SOPHIST: GRANT MORRISON’S ANIMAL MAN IAN HORNSBY In our culture, the decisive political conflict, which governs every conflict, is that between the animality and the humanity of man. (Agamben) The Italian philosopher Giorgio Agamben, in his book The Open: Man and Animal (2004), argues that while in early modern western philosophy, at least since Descartes, the human has been consistently described as the separation of body and mind, we would do better to re-describe the human, as that which results from the practical and political division of humanity from animality. After beginning with a brief outline of Agamben’s concept of ‘Bare Life’, as the empty interval between human and animal, which is neither “human life” nor “animal life,” but a life separated and excluded from itself; I will closely examine these ideas in relation to Grant Morrison’s DC Vertigo comic Animal Man (1988-90) to disclose aspects of sophist logic displaced in Agamben’s text. 1 § 1 Bare Life The concept of ‘bare life’ (2004, 38) is central to the philosophy of Agamben, not least, because he sees this empty interval between the animal and the human as the site for rethinking the future of politics and philosophy and preventing the onward progress of the ‘anthropological machine’ (2004, 37). A term he uses to describe the mechanism that has and continues to produces our recognition of what it means to be human. As Agamben states ‘It is an optical Machine constructed of a series of mirrors in which man, looking at himself, sees his own image always already deformed in the features of an ape. -

How Superman Developed Into a Jesus Figure

HOW SUPERMAN DEVELOPED INTO A JESUS FIGURE CRISIS ON INFINITE TEXTS: HOW SUPERMAN DEVELOPED INTO A JESUS FIGURE By ROBERT REVINGTON, B.A., M.A. A Thesis Submitted to the School of Graduate Studies in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts McMaster University © Copyright by Robert Revington, September 2018 MA Thesis—Robert Revington; McMaster University, Religious Studies McMaster University MASTER OF ARTS (2018) Hamilton, Ontario, Religious Studies TITLE: Crisis on Infinite Texts: How Superman Developed into a Jesus Figure AUTHOR: Robert Revington, B.A., M.A (McMaster University) SUPERVISOR: Professor Travis Kroeker NUMBER OF PAGES: vi, 143 ii MA Thesis—Robert Revington; McMaster University, Religious Studies LAY ABSTRACT This thesis examines the historical trajectory of how the comic book character of Superman came to be identified as a Christ figure in popular consciousness. It argues that this connection was not integral to the character as he was originally created, but was imposed by later writers over time and mainly for cinematic adaptations. This thesis also tracks the history of how Christians and churches viewed Superman, as the film studios began to exploit marketing opportunities by comparing Superman and Jesus. This thesis uses the methodological framework of intertextuality to ground its treatment of the sources, but does not follow all of the assumptions of intertextual theorists. iii MA Thesis—Robert Revington; McMaster University, Religious Studies ABSTRACT This thesis examines the historical trajectory of how the comic book character of Superman came to be identified as a Christ figure in popular consciousness. Superman was created in 1938, but the character developed significantly from his earliest incarnations.