Mpc – Migration Policy Centre

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

United Nations Interagency Health-Needs-Assessment Mission

United Nations interagency health-needs-assessment mission Southern Turkey, 4−5 December 2012 IOM • OIM Joint Mission of WHO, UNFPA, UNHCR, UNICEF and IOM 1 United Nations interagency health-needs-assessment mission Southern Turkey, 4−5 December 2012 Joint Mission of WHO, UNFPA, UNHCR, UNICEF and IOM Abstract On 4–5 December 2012, a United Nations interagency health-needs-assessment mission was conducted in four of the 14 Syrian refugee camps in southern Turkey: two in the Gaziantep province (İslahiye and Nizip camps), and one each in the provinces of Kahramanmaraş (Central camp) and Osmaniye (Cevdetiye camp). The mission, which was organized jointly with the World Health Organization (WHO), the Ministry of Health of Turkey and the Disaster and Emergency Management Presidency of the Prime Ministry of Turkey (AFAD), the United Nations Populations Fund (UNFPA), the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for refugees (UNHCR) and comprised representatives of the International Organization for Migration (IOM). It was coordinated by WHO. The primary goals of the mission were: to gain a better understanding of the capacities existing in the camps, including the health services provided, and the functioning of the referral system; and, on the basis of the findings, identify how the United Nations agencies could contribute to supporting activities related to safeguarding the health of the more than 138 000 Syrian citizens living in Turkey at the time of the mission. The mission team found that the high-level Turkish health-care services were accessible to and free of charge for all Syrian refugees, independent of whether they were living in or outside the camps. -

Sabiha Gökçen's 80-Year-Old Secret‖: Kemalist Nation

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO ―Sabiha Gökçen‘s 80-Year-Old Secret‖: Kemalist Nation Formation and the Ottoman Armenians A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Communication by Fatma Ulgen Committee in charge: Professor Robert Horwitz, Chair Professor Ivan Evans Professor Gary Fields Professor Daniel Hallin Professor Hasan Kayalı Copyright Fatma Ulgen, 2010 All rights reserved. The dissertation of Fatma Ulgen is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication on microfilm and electronically: _______________________________________________________________ _______________________________________________________________ _______________________________________________________________ _______________________________________________________________ _______________________________________________________________ _______________________________________________________________ Chair University of California, San Diego 2010 iii DEDICATION For my mother and father, without whom there would be no life, no love, no light, and for Hrant Dink (15 September 1954 - 19 January 2007 iv EPIGRAPH ―In the summertime, we would go on the roof…Sit there and look at the stars…You could reach the stars there…Over here, you can‘t.‖ Haydanus Peterson, a survivor of the Armenian Genocide, reminiscing about the old country [Moush, Turkey] in Fresno, California 72 years later. Courtesy of the Zoryan Institute Oral History Archive v TABLE OF CONTENTS Signature Page…………………………………………………………….... -

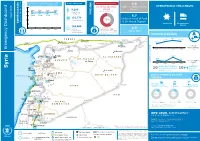

Syria External Dashboard April 2016 -Draft for May 19

3.89 million people assisted in April OTHER PROGRAMMES NET FUNDING REQUIREMENTS* 4.8 through General Food Distributions OPERATIONAL CHALLENGES Assisted 5 Emergency Operation million refugees in the 200339 4.0m 4.0m 4.0m 4.0m 8,200 Region MAY-OCTOBER 2016 4 Pregnant and Targeted 3.89m lactating women FUNDING 3 3.65m 3.79m 3.71m 8.7 April 2016 135,779 million in need of Food 2 Children-Nutrition 70% Emergency Operation 200339 Emergency Operation & Livelihood Support BENEFICIARIES 1 Insecurity Humanitarian 160,000 Access 0 Net Funding 6.5 JAN FEB MAR APR students Requirements: 230m Total Requirements: 331m million IDPs Snack Programme *does not include pledges made at the London Conference Source: WFP,12 May 2016 COMMON SERVICES Cizre- 7,100 T U R K E Y g! 6,071 Sanliurfa Kiziltepe-Ad Nusaybin-Al 5,809 ! Darbasiyah Qamishli ! Peshkabour Gaziantep Ayn al 3,870 Adana ! Ceylanpinar-Ras g! !! g! ! Arab dg" Islahiye Karkamis-Jarabulus Al Ayn g! Akcakale-Tall Qamishly Al Yaroubiya R CARGO "! g! Bab As ! Abiad g! Qamishli * - Rabiaa ! d g g! TE c *Salama Cobanbey TRANSPORTED Emergency Dashboard Dashboard Emergency 3 Mercin ! g! JAN FEB MAR APR (m ) ! ! g!! g LUS !! Manbij ! !Al-Hasakeh C ! ! Reyhanli! - S * ! C !!Bab !al Hawa I 1,700 ! ! !! T !Antioch !!! ! !!!!!Aleppo g! !!!!!! !!!!!!!! A L - H A S A K E H S !!!!!!!!! ! ! I !! !! ! 929 Karbeyaz !!! A R - R A Q Q A 840 Yayladagi ! !! OG 648 ! Id!leb! A L E P P O ! L RELIEF GOODS g! ! Ar-Raqqa g! !!!! ! ! ! ! !! !! !! STORED ! !! ! !! !!!!! JAN FEB MAR APR (m3) !!I D L E!!B!! ! !!!!!!! !!! !!!! -

Türkiye'de Turizm Ulaştirmasi 21

TÜRKİYE’DE TURİZM ULAŞTIRMASI (Tourism Transportation in Turkey) Dr. SUNA DOĞANER* ÖZET: Ulaşım seyehati mümkün kılar ve bu sebepten turizmin önemli bir parça sıdır. Ulaşım herşeyden önce turizmin gelişiminin sebebi ve sonucudur: Ula şım sistemlerinin gelişimi turizmi canlandırır, turizmin yayılması da ulaşımı geliştirir. Karayolu ulaşımı, Türkiye’de pekçok sayfiyenin, tarihi ve kültürel merkezin doğması ve gelişmesinde önemli bir rol oynamıştır. Türkiye’de pek çok şehire hava ulaşımının sağlanması uzak yerlere ulaşımı kolaylaştırmıştır. Organize turların gelişmesi aynı zamanda hava ulaşımını canlandırmıştır. De nizde seyehat oldukça zevklidir ve gemi seyehatlerine olan ilgi artmaktadır. Uluslararası hatlarda feribot seferleri Adriyatik (İzmir-Venedik ve Antalya- Venedik arasında) ve Kıbrıs hatlarında yapılmaktadır ayrıca iç hatlarda feri bot seferleri vardır. Buharlı Tren Turları Türkiye’de demiryolu ile seyehatin gelişmesinde önemli bir rol oynamıştır. Sonuç olarak Türkiye’de ulaşım iç ve dış turizmde önemli bir rol oynamaktadır. ABSTRACT: Transport, which makes travel possible, is therefore an integral part of to urism. Transport has been at once a cause an effect of the growth of tourism: improved transport facilities have stimulated tourism, the expansion of tou- ırsm has stimulated transport. Road transport has been a very important fac tor affecting the rise and growth of many seaside resorts, historic and cultural centers in Turkey. The inception of air transport to many cities made easy long distance transport posible in Turkey. The development of package tours has also stimulated air transport. Sea travel is in itself a pleasure and cruising ho lidays have grown in importance. Ferry -boat cruises on international lines are Adriatic (between İzmir-Venice and Antalya-venice) and Cyprus services. -

(Kızıldağ, Hatay and Islahiye, Antep) and Tauric Ophiolite Belt (Pozantı-Karsantı, Adana), Turkey

The Mineralogy and Chemistry of the Chromite Deposits of Southern (Kızıldağ, Hatay and Islahiye, Antep) and Tauric Ophiolite Belt (Pozantı-Karsantı, Adana), Turkey M. Zeki Billor1 and Fergus Gibb2 1 Visiting researcher, Department of Geoscience The University of Iowa Iowa City, IA 52242, USA (Permanent address: Çukurova University, Department of Geology, 01330 Adana, Turkey) 2 Department of Engineering Materials, University of Sheffield, Sheffield, S1 3JD, UK e-mail: [email protected] Introduction recognized in Turkey are: a) the southern (peri- The Tethyan ophiolite belt is one of the Arabic) ophiolite belt, b) the Tauric (median) longest ophiolite belts in the world, extending from ophiolite belt, and c) the northern ophiolite belt. Spain to the Himalayas. The geochemistry, genesis In this study, chromite deposits from the and geological time scale of the ophiolite belt southern and Tauric ophiolite belts have been varies from west to east. It shows its maximum studied. In the study area, the Southern and Tauric development in Turkey. The tectonic setting of the ophiolites have more than 2000 individual chromite Turkish ophiolite belt is a direct result of the deposits throughout the ophiolite; geographically, closure of the Tethyan Sea. the chromite pods are clustered in four locations: Ophiolites in Turkey are widespread from the Karsantı and Gerdibi-Cataltepe districts in the west to east and show tectonically complex Tauric ophiolite belt and the Hatay and Islahiye structures and relationships with other formations area in -

Syrian Refugee Health Profile

SYRIAN REFUGEE HEALTH PROFILE U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Centers for Disease Control and Prevention National Center for Emerging and Zoonotic Infectious Diseases Division of Global Migration and Quarantine December 22, 2016 Syrian Refugees • Priority Health Conditions • Background • Population Movements and Refugee Services in Countries of Asylum • Healthcare and Conditions in Camps or Urban Settings • Medical Screening of U.S.-Bound Refugees • Post-Arrival Medical Screening • Health Information Priority Health Conditions The following health conditions are considered priority conditions that constitute a distinct health burden for the Syrian refugee population: • Anemia • Diabetes • Hypertension • Mental Illness Background The Syrian conflict, which began in 2011, has resulted in the largest refugee crisis since World War II, with millions of Syrian refugees fleeing to neighboring countries including Lebanon, Jordan, and Turkey [1]. Syrian refugees have also fled to Europe, with many crossing the Mediterranean Sea in order to reach European Union-member nations, mainly Greece, then traveling north to countries such as Germany and Sweden. Syria’s pre-war population of 22 million people has been reduced to approximately 17 million, with an estimated 5 million having fled the country [2, 3], and more than 6.5 million displaced within Syria [4]. As fighting has continued across the country, an increasing number of health facilities have been heavily damaged or destroyed by attacks, leaving thousands of Syrians without access to urgent and essential healthcare services [5]. Geography The Syrian Arab Republic (Syria) is located in the Middle East, bordering Lebanon, Turkey, Iraq, Jordan, and Israel; it is also bordered by the Mediterranean Sea to the west (Figure 1). -

Kuva-Yı Islahiye'nin Musul Ve Kerkük'teki Faaliyetleri Activity Of

GÜ, Gazi Eğitim Fakültesi Dergisi, Cilt 27, Sayı 1(2007) 237-248 Kuva-yı Islahiye’nin Musul ve Kerkük’teki Faaliyetleri Activity of Kuva-yı Islahiye in Mousul and Kerkukh Nuri YAVUZ G,Ü, Gazi Eğitim Fakültesi Tarih Eğitimi ABD, Ankara -TÜRKİYE ÖZET Osmanlılar devrinde Musul ve Kerkük’teki başlıca sorunlar aşiret kavgaları, dini farklılık taşıyan grupların çıkardıkları olaylardan ibaret olmuştur. Osmanlı Devleti 19. yüzyılın ikinci yarısında bölgedeki problemleri çözerek düzeni sağlamayı son bir defa daha denemiştir. Kuva-yı İslahiye bu işte en önemli vazifeyi üstlenmiştir. Fırka-i Islahiye’nin Çukurova ve Güneydoğu Anadolu’daki başarılı iskân ve askeri faaliyetlerinin dışında Musul ve Kerkük’teki faaliyetleri de günümüzde daha da önemli bir hale gelmiş bulunmaktadır. Anahtar Kelimeler: Kuva-yı ıslahiye, Fırka-i ıslahiye, Musul, Kerkük ABSTRACT The major problems in Mousul and Kerkukh in Ottoman era were clashes between clans and skirmishes caused by the groups coming from different religions . The Ottomans made one final attempt to solve the problems and reestablished the harmony in the second half of the 19th century . Kuva-yı İslahiye assumed an important role in this process . As well as the successful settlement and military activities in Çukurova and Southeast Anatolia the activities of Fırka-i Islahiye in Mousul and Kerkukh have become important today . Key words: Kuva-yı ıslahiye, Fırka-i ıslahiye, Mousul, Kerkukh 238 GÜ, Gazi Eğitim Fakültesi Dergisi, Cilt 27, Sayı 1(2007) 237-248 1. Giriş Musul ve Kerkük civarına Türklerin gelmesi IX. yüzyılda Abbasi halifeleri Memun ve Mutasım devrinde olmuştur. 1055 yılında büyük Selçuklu sultanı Tuğrul Bey’in Bağdat’a gelmesiyle Irak coğrafyasının içinde bulunan Kerkük ve Musul da Türklerin hakimiyetine geçmiştir.1 Öyle ki, IX. -

EUROPEAN AGREEMENT on IMPORTANT INTERNATIONAL COMBINED TRANSPORT LINES and RELATED INSTALLATIONS (AGTC) United Nations

ECE/TRANS/88/Rev.6 ECONOMIC COMMISSION FOR EUROPE EUROPEAN AGREEMENT ON IMPORTANT INTERNATIONAL COMBINED TRANSPORT LINES AND RELATED INSTALLATIONS (AGTC) DONE AT GENEVA ON 1 FEBRUARY 1991 __________________ United Nations 2010 Note: This document contains the text of the AGTC Agreement including the procès-verbal of rectification as notified in Depositary Notification C.N.347.1992.TREATIES-7 dated 30 December 1992. It also contains the following amendments to the AGTC Agreement: (1) Depositary Notifications C.N.345.1997.TREATIES-2 and C.N.91.1998.TREATIES-1. Entry into force on 25 June 1998. (2) Depositary Notification C.N.230.2000.TREATIES-1 and C.N.983.2000.TREATIES-2. Entry into force on 1 February 2001. (3) Depositary Notification C.N.18.2001.TREATIES-1 and C.N.877.2001.TREATIES-2. Entry into force on 18 December 2001. (4) Depositary Notification C.N.749.2003.TREATIES-1 and C.N.39.2004.TREATIES-1. Entry into force on 16 April 2004. (5) Depositary Notification C.N.724.2004.TREATIES-1 and C.N.6.2005.TREATIES-1. Entry into force on 7 April 2005. (6) Depositary Notification C.N. 646.2005.TREATIES-1 and C.N.153.2006.TREATIES-1. Entry into force on 20 May 2006. (7) Depositary Notification C.N.594.2008.TREATIES-3 and C.N. 76.2009.TREATIES-1. Entry into force on 23 May 2009. (8) Depositary Notification C.N.623.2008.TREATIES-4 and C.N 544.2009.TREATIES-2. Entry into force on 10 December 2009. The present document contains in a single, non-official document the consolidated text of the AGTC Agreement including the basic instrument, its amendments and corrections that have come into force by the dates indicated. -

Il Ilçe Nüfus Sayisi Mevcut Eczane Sayisi Max

MEVCUT MAX. NÜFUS KONTENJAN İL İLÇE ECZANE AÇILABİLECEK KATSAYI SAYISI SAYISI SAYISI ECZANE SAYISI ADANA ALADAĞ 17221 3 4 1 5 ADANA CEYHAN 159243 49 45 -4 3 ADANA ÇUKUROVA 346505 103 99 -4 0 ADANA FEKE 18534 3 5 2 6 ADANA İMAMOĞLU 29748 11 8 -3 3 ADANA KARAİSALI 22230 7 6 -1 5 ADANA KARATAŞ 21862 4 6 2 3 ADANA KOZAN 128153 44 36 -8 3 ADANA POZANTI 20954 7 5 -2 3 ADANA SAİMBEYLİ 16572 3 4 1 5 ADANA SARIÇAM 138139 30 39 9 0 ADANA SEYHAN 771947 273 220 -53 1 ADANA TUFANBEYLİ 18234 3 5 2 5 ADANA YUMURTALIK 18463 2 5 3 3 ADANA YÜREĞİR 421455 112 120 8 1 ADIYAMAN BESNİ 77404 14 22 8 4 ADIYAMAN ÇELİKHAN 15387 2 4 2 4 ADIYAMAN GERGER 21458 2 6 4 6 ADIYAMAN GÖLBAŞI 47406 13 13 0 3 ADIYAMAN KAHTA 117865 25 33 8 5 ADIYAMAN MERKEZ 279037 79 79 0 3 ADIYAMAN SAMSAT 9180 1 2 1 4 ADIYAMAN SİNCİK 18750 1 5 4 6 ADIYAMAN TUT 10697 2 3 1 5 AFYONKARAHİSAR BAŞMAKÇI 10541 3 3 0 3 AFYONKARAHİSAR BAYAT 8280 2 2 0 4 AFYONKARAHİSAR BOLVADİN 45710 14 13 -1 3 AFYONKARAHİSAR ÇAY 33354 11 9 -2 3 AFYONKARAHİSAR ÇOBANLAR 14105 3 4 1 4 AFYONKARAHİSAR DAZKIRI 11193 3 3 0 3 AFYONKARAHİSAR DİNAR 48687 21 13 -8 3 AFYONKARAHİSAR EMİRDAĞ 38991 9 11 2 3 AFYONKARAHİSAR EVCİLER 7842 3 2 -1 3 AFYONKARAHİSAR HOCALAR 10520 1 3 2 5 AFYONKARAHİSAR İHSANİYE 28767 6 8 2 4 AFYONKARAHİSAR İSCEHİSAR 24363 4 6 2 3 AFYONKARAHİSAR KIZILÖREN 2643 1 0 -1 4 AFYONKARAHİSAR MERKEZ 268461 97 76 -21 2 AFYONKARAHİSAR SANDIKLI 57211 19 16 -3 3 AFYONKARAHİSAR SİNANPAŞA 41914 8 11 3 4 AFYONKARAHİSAR SULTANDAĞI 16480 9 4 -5 3 AFYONKARAHİSAR ŞUHUT 38061 7 10 3 4 AĞRI DİYADİN 45395 4 12 8 6 AĞRI DOĞUBAYAZIT -

The Pesticide Using Habits of Red Pepper Breeders in Islahiye and Nurdaği Districts of Gaziantep Province and Attitudes Among the Environment

Turkish Journal of Agricultural and Natural Sciences Special Issue: 1, 2014 TÜRK TURKISH TARIM ve DOĞA BİLİMLERİ JOURNAL of AGRICULTURAL DERGİSİ and NATURAL SCIENCES www.turkjans.com The Pesticide Using Habits Of Red Pepper Breeders In Islahiye And Nurdaği Districts Of Gaziantep Province And Attitudes Among The Environment Zekeriya KANTARCI, Serhan CANDEMİR East Mediterranean Transitional Zone Agricultural Research of Station Kahramanmaraş/TURKEY Abstract Until the early 80s, all around the world and especially in the developed countries increasing yield per unit area and thus lowering the expenses has been the major policy objective. However, the direct and indirect effects of intensive usage of inputs on natural resources became a major concern for both the environment and public health by 80s. Conscious and proper usage of pesticides enables the user to destroy the pests and weeds whereas the unconscious usage harms beneficial insects, microorganisms, plants, water supplies and even public health. The aim of this study is to identify the pesticides usage habits of chili pepper breeding farmers of Islahiye and Nurdağı, where the all chili pepper planting area is located and meanwhile investigating the attitudes among the environment. To do so, a survey is constructed and applied via interviews and data obtained is analyzed via the use of proper statistical package programs and the results are interpreted. Key Words: Red Pepper, Pesticide, Environment, Gaziantep Özet Dünyada özellikle gelişmiş ülkeler başta olmak üzere, bütün ülkelerde 1980'li yılların başlarına kadar tarımsal üretimi, birim alan verimini yükselterek artırmak ve bu yolla üretim maliyetini azaltmak, başlıca tarım politikası hedefi olmuştur. Ancak yoğun girdi kullanımının doğal kaynaklar ve insan sağlığı üzerindeki doğrudan ve dolaylı olumsuz etkileri, 1980'li yıllardan sonra gelişmiş ülkelerden başlayarak bütün dünyada en önemli kalkınma ve çevre sorunu olarak ortaya çıkmıştır. -

SYRIA Dashboard

4.16 million people assisted in August OTHER PROGRAMMES NET FUNDING REQUIREMENTS through General Food Distributions 4.8 August 2016 EMOP 200339 5 million refugees in the Assisted 4.16m 4.2m Region 4.0m 4.16m* 11,376 $0m**(0%) Humanitarian 2016 4 Pregnant and Net Funding 4.0m 4.0m 4.0m Requirements Access 4.04m Nursing Women 3 FUNDING 8.7 Four Month Outlook* equirements 196,514 R million in need of Food 2 ational Planned ational Children-Nutrition r otal & Livelihood Support T CHALLENGES Ope OPERATIONAL m: Emergency Operation 200339 September BENEFICIARIES 1 Insecurity Students-Fortied $228 m 228 0 School Snack is on-hold $ Resourced 6.1 MAY June July Aug within the school *EMOP will be terminated end of 2016, a new operation million IDPs summer break will start in 2017 *figures are being reconciled **Including pledges and solid forecasts COMMON SERVICES As of 14 September 2016 9,238 Cizre- 8,014 T U R K E Y g! 6,632 Sanliurfa Kiziltepe-Ad Nusaybin-Al ! Darbasiyah Qamishli ! Peshkabour Gaziantep Ayn al 3,073 Adana ! Ceylanpinar-Ras g! g!! g! ! Arab d" CARGO Islahiye Karkamis-Jarabulus Al Ayn Akcakale-Tall Al Yaroubiya g! QamiQamishlishly * TRANSPORTED Bab As g! 3 ! d"! g! * g! Abiad g! - Rabiaa MAY JUN JUL AUG (m ) Emergency Dashboard Emergency Dashboard c Salama Cobanbey g! Mercin ! g!!! g! !! !Manbij Al-Hasakeh ! !! 3,982 Reyhanli - 1,595 * !! 1,192 !!Bab !al Hawa Antioch !! !! !!!!Aleppo ! g!!!!!!! !!!!!!! ! !!!!!!!! !! !! A L - H A S A K E H 725 !!!!!!! LOGISTICS CLUSTER LOGISTICS RELIEF GOODS Karbeyaz !!! ! A R - R A Q Q A Yayladagi -

Eadrcc Urgent Disaster Assistance Request

NATO OTAN Euro-Atlantic Disaster Response Centre Euro-Atlantique de Coordination Centre coordination des réactions (EADRCC) en cas de catastrophe Fax : +32-2-707.2677 (EADRCC) [email protected] Télécopie : +32-2-707.2677 [email protected] NON - CLASSIFIED EADRCC Situation Report Nº5 Syrian refugees camps in TURKEY (latest update in BOLD) Message Nº. : OPS(EADRCC)(2012)0118 Dtg : 04 June 2012, 10:30 UTC From: : Euro-Atlantic Disaster Response Coordination Centre To : Points of Contact for International Disaster Response in NATO and partner Countries Precedence : Priority Originator : Duty Officer Tel: +32-2-707.2670 Approved by : Head EADRCC Tel: +32-2-707.2673 Reference : OPS(EADRCC)(2012)0046 This report consists of : - 6 - pages 1. In accordance with the procedures at reference, EADRCC has received on 13 April 2012 a disaster assistance request from Turkey dated 13 April 2012 19:09 UTC. 2. United Nations Organisations and the European Union have also received a formal request from Turkey. 3. General Situation 3.1. Recent events in Syria have resulted in a flow of Syrian refugees into Turkey and refugee camps have been set up on the Turkish side of the Syrian border. Turkey is putting every effort to meet the needs of the Syrian refugees to the extent possible making full use of its means and capabilities. 3.2. On 31 May – 01 June 2012, 135 Syrian citizens voluntarily returned home and 395 Syrian citizens arrived in Turkey. 3.3. The number of refugees arriving from Syria is 45.197 and the number that have returned to Syria is 20.764.