To See a Rabbit Storey Clayton

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Aeneid with Rabbits

The Aeneid with Rabbits: Children's Fantasy as Modern Epic by Hannah Parry A thesis submitted to the Victoria University of Wellington in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Victoria University of Wellington 2016 Acknowledgements Sincere thanks are owed to Geoff Miles and Harry Ricketts, for their insightful supervision of this thesis. Thanks to Geoff also for his previous supervision of my MA thesis and of the 489 Research Paper which began my academic interest in tracking modern fantasy back to classical epic. He must be thoroughly sick of reading drafts of my writing by now, but has never once showed it, and has always been helpful, enthusiastic and kind. For talking to me about Tolkien, Old English and Old Norse, lending me a whole box of books, and inviting me to spend countless Wednesday evenings at their house with the Norse Reading Group, I would like to thank Christine Franzen and Robert Easting. I'd also like to thank the English department staff and postgraduates of Victoria University of Wellington, for their interest and support throughout, and for being some of the nicest people it has been my privilege to meet. Victoria University of Wellington provided financial support for this thesis through the Victoria University Doctoral Scholarship, for which I am very grateful. For access to letters, notebooks and manuscripts pertaining to Rosemary Sutcliff, Philip Pullman, and C.S. Lewis, I would like to thank the Seven Stories National Centre for Children's Books in Newcastle-upon-Tyne, and Oxford University. Finally, thanks to my parents, William and Lynette Parry, for fostering my love of books, and to my sister, Sarah Parry, for her patience, intelligence, insight, and many terrific conversations about all things literary and fantastical. -

A Symphonic Discussion of the Animal in Richard Adams' Watership Down

Centre for Languages and Literature English Studies A Symphonic Discussion of the Animal in Richard Adams’ Watership Down Elisabeth Kynaston ENGX54 Degree project in English Literature Spring 2020 Centre for Languages and Literature Lund University Supervisor: Cecilia Wadsö-Lecaros Abstract The purpose of this essay is to suggest a new reading of Richard Adams’ Watership Down (1972) by adopting the recently new discipline of Animal Studies. Adams follows a long tradition of talking animals in literature, which still to this day, is an important part of the English literary canon. Throughout this essay, I shall focus on several aspects of the novel. I will look at the anthropomorphized animals and examine how the animals are portrayed in the text. I will seek to offer a structural analysis of Adams’ novel using the structure of the symphony. The essay offers a background discussion of Animal Studies as a theoretical discipline. In addition, the background will provide the reader with a description of how and why the structure of the symphony can function as a method to analyse Adams’ novel. The analysis has been divided into five parts where Jakob von Uexküll’s and Mario Ortiz-Robles’ research will serve as a basis for my discussion as I seek to provide a deeper understanding of how our perception of the animal in literature affects our idea of the animal in our human society. Table of Contents 1. Introduction 2. Background 3. First Movement – The Journey 1. Theme One – “Nature/Rabbit” 2. Theme Two – The Human 3. The Rabbit as a Subject 4. -

FANTASY GAMES and SOCIAL WORLDS Simulation As Leisure

>> Version of Record - Sep 1, 1981 What is This? Downloaded from sag.sagepub.com at SAGE Publications on December 8, 2012 FANTASY GAMES AND SOCIAL WORLDS Simulation as Leisure GARY ALAN FINE University of Minnesota As the longevity and success of this journal attest, simulation games have had a considerable impact on the scholarly commun- ity, spawning cottage industries and academic specialties. Simu- lation gaming is now well established as a legitimate academic pursuit and teaching tool. Simultaneous with the growth of educational games, the 1970s witnessed the development and popularity of other role-playing games, essentially simulations, which have enjoyment and fantasy as their major goals. These games are known generically as fantasy role-playing games. My intent in this article is to describe the games, discuss the relationship of these games to similar activities (including educational simulations), describe the players, and examine their reasons for participating in this social world. By studying these play forms, researchers who specialize in educational simulations can observe parallels in this leisure activity. AUTHOR’S NOTE: The author would like to thank Sherryl Kleinman and Linda Hughes for comments on previous drafts of this article. SIMULATION ~c GAMES, Vol. 12 No. 3, September I981 251-279 @ 1981 Sage Pubhcations, Inc. 251 Downloaded from sag.sagepub.com at SAGE Publications on December 8, 2012 252 WHAT IS FANTASY ROLE-PLAY GAMING? A &dquo;[fantasy] role-playing game&dquo; has been defined as &dquo;any game which allows a number of players to assume the roles of imaginary characters and operate with some degree of freedom in an imaginary environment&dquo; (Lortz, 1979b: 36). -

Tales from the Wood

Tales from The Wood Role playing Game Simon Washbourne CREDITS Initial concept © 2005 by Simon Washbourne & Mark George All rights reserved. Game design, development, editing, & layout Simon Washbourne Artwork Cover: Gill Pearce Interior: Simon Washbourne, Gill Pearce, Helen Roberts & Val Bertin Thanks to all the play testers Annette Washbourne, Nigel Uzzell, Janine Uzzell, Alyson George, Robert Watkins, Rob- ert Irwin, Gary Collett, Leigh Wakefield, Phil Chivers, Phil Ratcliffe and members of Innsworth Wargames and Role Playing United Kingdom (IWARPUK) Recommended Fiction William Horwood; Duncton Wood, Duncton Quest, Duncton Found, Duncton Tales, Duncton Rising, Duncton Stone (moles) Gerry Kilworth; Frost Dancers (hares), Hunters Moon (foxes) A.R. Lloyd; Marshworld, Witchwood, Dragon Pond (weasels) Denys Watkins Pitchford (B.B); Little Grey Men, Down the Bright Stream (gnomes) Chris Freddi; Pork & other tales (several different types of animal) Michael Tod; The Silver Tide, The Second Wave, The Golden Flight (squirrels) Richard Adams; Watership Down (rabbits) Aeron Clement; The Cold Moons (badgers) Brian Carter; Night World (badgers) Colin Dann; The Animals of Farthing Wood, In the Grip of Winter, Fox's Feud, Fox Cub Bold, The Siege of White Deer Park, In the Path of Storm, Battle for the Park, Farthing Wood - The Adventure Begins (several different types of animal) Recommended Non-Fiction Any good natural history books would be highly useful, but these are some of those con- sulted when designing Tales from The Wood. Ron Freethy; Man -

Enrichment Reading (Pdf)

1 Enrichment Reading 2015 Adams, Douglas. The Ultimate Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy. In this collection of novels, Arthur Dent is introduced to the galaxy at large when he is rescued by an alien friend seconds before Earth's destruction and embarks on a series of amazing adventures. Adams, Richard. Watership Down. “Set in England's Downs, a once idyllic rural landscape, this stirring tale of adventure, courage, and survival follows a band of very special creatures on their flight from the intrusion of man and the certain destruction of their home. Led by a stouthearted pair of brothers, they journey forth from their native Sandleford Warren through the harrowing trials posed by predators and adversaries, to a mysterious promised land and a more perfect society.” Alexander, Kwame. The Crossover. Fourteen-year-old twin basketball stars Josh and Jordan wrestle with highs and lows on and off the court as their father ignores his declining health. Austen, Jane. Pride and Prejudice. “One of the most universally loved and admired English novels, Pride and Prejudice was penned as a popular entertainment, but the consummate artistry of Jane Austen (1775–1817) transformed this effervescent tale of rural romance into a witty, shrewdly observed satire of English country life that is now regarded as one of the principal treasures of English language. In a remote Hertfordshire village, far off the good coach roads of George III's England, a country squire of no great means must marry off his five vivacious daughters. At the heart of this all- consuming enterprise are his headstrong second daughter Elizabeth Bennet and her aristocratic suitor Fitzwilliam Darcy — two lovers whose pride must be humbled and prejudices dissolved before the novel can come to its splendid conclusion.” Barrow, Randi. -

Richard Adams 6.2 the Lion, the Witch & the Wardrobe

AR How did it make you feel? Star Rating Watership Down - Richard Adams 6.2 The Lion, the Witch & the Wardrobe - CS Lewis 5.7 The Secret Garden - Frances Hodgson-Burnett 3.6 Treasure Island - Robert Louis Stevenson 8.3 Black Beauty - Anna Sewell 7.7 AR How did it make you feel? Star Rating Kensuke’s Kingdom - Michael Morpurgo 4.7 Lord of the Flies - William Golding 5.0 How to Train Your Dragon - Cressida Cowell 6.7 AR How did it make you feel? Star Rating Keeper - Mal Peet 5.1 The Kick Off - Dan Freedman 4.9 AR How did it make you feel? Star Rating The Hound of the Baskervilles - Arthur Conan Doyle 8.3 Murder on the Orient Express - Agatha Christie 6.2 Thief Lord - Cornelia Funke 4.8 AR How did it make you feel? Star Rating The Woman in Black - Susan Hill 7.2 Twilight - Stephanie Meyer 4.9 AR How did it make you feel? Star Rating The Owl Service - Alan Garner 3.7 King of the Middle March - Kevin Crossley-Holland 4.2 AR How did it make you feel? Star Rating Wonder - RJ Palacio 4.8 Holes - Louis Sachar (pronounced ‘sacker’) 4.6 The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night Time - Mark Haddon 5.4 AR How did it make you feel? Star Rating Noughts & Crosses - Malorie Blackman 4.0 AR How did it make you feel? Star Rating The Boy in the Striped Pyjamas - John Boyne 5.8 War Horse - Michael Morpurgo 5.9 Goodnight Mr Tom - Michelle Magorian 5.1 AR How did it make you feel? Star Rating Mr Stink - David Walliams 4.7 The Secret Diary of Adrian Mole - Sue Townsend 5.1 AR How did it make you feel? Star Rating Matilda - Roald Dahl 5.0 Northern Lights - -

Where Will Books Take You?

What We’re Reading UPPER SCHOOL Where will books take you? Kent Denver School | 4000 E. Quincy Ave., Englewood, CO 80113 Table of Contents Upper School Reading Program Statement 5 Upper School Recommendations 6 The Reader’s Bill of Rights 108 3 Thank you to the students, faculty, and staff of Kent Denver School for taking the time to submit the thoughtful recommendations you will find in this guide. Use it to look for adventure, to challenge your mind, to go on a journey. Come get lost in a book. “It is what you read when you don’t have to that determines what you will be when you can’t help it.” Oscar Wilde 4 The Upper School Program: The Freedom and Pleasure of Choice Everyone is encouraged to read at least three texts of his or her choice, and the faculty acknowledges an expansive view of what constitutes a text. Books, of course, are texts but consider also newspapers, magazines and blogs. Read anything, as long as you care about it, you enjoy it and it makes you think. Guidance is readily available by reviewing this booklet. When you come back from the summer, the faculty hope you will be rested and recharged. Be prepared to share in advisory and in your classes, your own reading experiences and recommenda- tions. A note to students and parents: Students and faculty have sub- mitted the following Kent Denver recommendations; these titles are suggested as a way of offering choice for students. The titles offer a wide variety of reading interests, levels and content. -

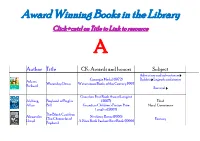

Award Winning Books in the Library Click+Cntrl on Title to Link to Resource A

Award Winning Books in the Library Click+cntrl on Title to Link to resource A Author Title CK: Awards and honors Subject Adventure and adventurers › Carnegie Medal (1972) Rabbits › Legends and stories Adams, Watership Down Waterstones Books of the Century 1997 Richard Survival › Guardian First Book Award Longlist Ahlberg, Boyhood of Buglar (2007) Thief Allan Bill Guardian Children's Fiction Prize Moral Conscience Longlist (2007) The Black Cauldron Alexander, Newbery Honor (1966) (The Chronicles of Fantasy Lloyd A Horn Book Fanfare Best Book (1966) Prydain) Author Title CK: Awards and honors Subject The Book of Three Alexander, A Horn Book Fanfare Best Book (1965) (The Chronicles of Fantasy Lloyd Prydain Book 1) A Horn Book Fanfare Best Book (1967) Alexander, Castle of Llyr Fantasy Lloyd Princesses › A Horn Book Fanfare Best Book (1968) Taran Wanderer (The Alexander, Fairy tales Chronicles of Lloyd Fantasy Prydain) Carnegie Medal Shortlist (2003) Whitbread (Children's Book, 2003) Boston Globe–Horn Book Award Almond, Cuban Missile Crisis, 1962 › The Fire-eaters (Fiction, 2004) David Great Britain › History Nestlé Smarties Book Prize (Gold Award, 9-11 years category, 2003) Whitbread Shortlist (Children's Book, Adventure and adventurers › Almond, 2000) Heaven Eyes Orphans › David Zilveren Zoen (2002) Runaway children › Carnegie Medal Shortlist (2000) Amateau, Chancey of the SIBA Book Award Nominee courage, Gigi Maury River Perseverance Author Title CK: Awards and honors Subject Angeli, Newbery Medal (1950) Great Britain › Fiction. › Edward III, Marguerite The Door in the Wall Lewis Carroll Shelf Award (1961) 1327-1377 De A Horn Book Fanfare Best Book (1950) Physically handicapped › Armstrong, Newbery Honor (2006) Whittington Cats › Alan Newbery Honor (1939) Humorous stories Atwater, Lewis Carroll Shelf Award (1958) Mr. -

Richard Adams Watership Down

Recommended Reading List – Year 6 This list is intended to be a guide to books suitable for children in Year 6. The list, covering a range of genres, is drawn from a number of sources including teachers own recommendations; the National Literacy Strategy’s recommended texts; reading lists suggested by other schools and the National Literacy Trust’s website. Some of the texts are more difficult to read than others and care should be taken when choosing those which your child might enjoy. Please discuss the book your child reads with him/her and remember it is important to keep reading to your child as they move through the school. Richard Adams Watership Down Joan Aiken The James III Sequence The Wolves of Willoughby Chase David Almond Skellig Kit’s Wilderness Neil Arksey Playing on the Edge Linda Aronson Kelp Bernard Ashley Johnny’s Blitz Little Soldier Rapid Sherry Ashworth What’s Your Problem? Joyce Annette Barnes Amistad Junior Novelization Joan Bauer Squashed Nina Bawden Carrie’s War The Outside Child The Real Plato Jones Leslie Beake Song of Be Tom Becker Darkside Gerard Benson This Poem Doesn’t Rhyme James Berry Classic Poems to Read Aloud Malorie Blackman Hacker Noughts and Crosses Thomas Bloor The Memory Prisoner Judy Blume Are you there God? It’s Me, Margaret Martin Booth Music on the Bamboo Radio Tim Bowler River Boy Midget Elinor M Brent-Dyer The Chalet School Series Linda Buckley- Archer Gideon the Cutpurse Melvin Burgess Billy Elliot Junk The Baby and Fly Pie Betsy Byars The Pinballs Cracker Jackson The Midnight Fox The Summer of the Swans Peter Carey The Big Bazoohley Lewis Carroll Alice’s Adventure in Wonderland G K Chesterton The Puffin Father Brown Stories Agatha Christie And then there were none John Christopher The Guardians Ann Coburn Worm Songs Peter Collington The Coming of the Surfman (Picture Book) Sir Arthur Conan Doyle The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes Susan Cooper Over Sea. -

Science Fiction & Fantasy Book Group List 2010 to 2020.Xlsx

Science Fiction & Fantasy Book List 2010-2020 Date discussed Title Author Pub Date Genre Tuesday, August 17, 2010 Eyes of the Overworld Jack Vance 1966 Fantasy Tuesday, September 21, 2010 Boneshaker Cherie Priest 2009 Science Fiction/Steampunk Tuesday, October 19, 2010 Hood (King Raven #1) Steve Lawhead 2006 Fantasy/Historical Fiction Tuesday, November 16, 2010 Hyperion (Hyperion Cantos #1) Dan Simmons 1989 Science Fiction Tuesday, December 21, 2010 Swords and Deviltry (Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser #1) Fritz Leiber 1970 Fantasy/Sword and Sorcery Tuesday, January 18, 2011 Brave New World Aldous Huxley 1931 Science Fiction/Dystopia Tuesday, February 15, 2011 A Game of Thrones (A Song of Ice and Fire, Book 1) George R.R. Martin 1996 Fantasy Tuesday, March 15, 2011 Hull Zero Three Greg Bear 2010 Science Fiction Tuesday, April 19, 2011 The Lies of Locke Lamora (Gentleman Bastard, #1) Scott Lynch 2006 Fantasy Tuesday, May 17, 2011 Never Let Me Go Kazuo Ishiguro 2005 Science Fiction/Dystopia Tuesday, June 21, 2011 The Name of the Wind (The Kingkiller Chronicle #1) Patrick Rothfuss 2007 Fantasy Tuesday, July 19, 2011 Old Man's War (Old Man's War, #1) John Scalzi 2005 Science Fiction NO MEETING Tuesday, August 16, 2011 Wednesday, September 07, 2011 Something Wicked This Way Comes (Green Town #2) Ray Bradbury 1962 Fantasy Wednesday, October 05, 2011 Altered Carbon (Takeshi Kovacs #1) Richard Morgan 2002 Science Fiction Wednesday, November 02, 2011 Prospero's Children Jan Siegel 1999 Fantasy Wednesday, December 07, 2011 Replay Ken Grimwood 1986 Science Fiction/Time Travel Wednesday, January 04, 2012 Raising Stony Mayhall Daryl Gregory 2011 Fantasy/Horror/Zombies Wednesday, February 01, 2012 The Moon Is a Harsh Mistress Heinlein, Robert 1966 Science Fiction Wednesday, March 07, 2012 Talion: Revenant Michael A. -

Season Seven: Animal Kingdom

SEASON SEVEN: ANIMAL KINGDOM The relationships humanity has with the living creatures of our world are as varied as the ones we have with each other. We have fought to keep from being eaten by the predatory, we have nurtured and raised domestics as companions and partners in labor, we have driven some to extinction, we have studied all to increase our understanding of life. Explore the wonders, rewards, and tragedies of the animal kingdom this season. Remember: This is a reference sheet only; check the Season Themes page on GoHavok.com to verify which months are open for submissions and which are closed. PARTNERS & PREDATORS (DEADLINE: November 7, 2021) Animals can be many things to humans: trusted mounts and fellow warriors, comfortable lap pets, sources of food, manual laborers, lie detectors, trained trackers and rescuers, formidable foes, and pernicious garden pests. What emotions do animals provoke in these relationships? Show us! (Publishes in January.) SWIMMERS & SOARERS (DEADLINE: December 5, 2021) There’s something about the blue expanse above that draws the human eye. Treat us to a closer look at flying creatures, their view from above and their eyrie homes. What if humans lived in the crags, riding the giant eagles? Delve into the sea, where life is broad and deep, mysterious, and rich with resources. What if we lived on islands and had trained water creatures who retrieved treasures from the depths? Or what if we lived under the sea ourselves? (Publishes in February.) DISCOVERIES & EXTINCTIONS (DEADLINE: January 3, 2021) There’s nothing like the thrill of discovery and the tragedy of permanent loss. -

The Tolkien Tradition

Volume 11 Number 1 Article 5 Summer 7-15-1984 The Tolkien Tradition Diana Paxson Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.swosu.edu/mythlore Part of the Children's and Young Adult Literature Commons Recommended Citation Paxson, Diana (1984) "The Tolkien Tradition," Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Charles Williams, and Mythopoeic Literature: Vol. 11 : No. 1 , Article 5. Available at: https://dc.swosu.edu/mythlore/vol11/iss1/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Mythopoeic Society at SWOSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Charles Williams, and Mythopoeic Literature by an authorized editor of SWOSU Digital Commons. An ADA compliant document is available upon request. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To join the Mythopoeic Society go to: http://www.mythsoc.org/join.htm Mythcon 51: A VIRTUAL “HALFLING” MYTHCON July 31 - August 1, 2021 (Saturday and Sunday) http://www.mythsoc.org/mythcon/mythcon-51.htm Mythcon 52: The Mythic, the Fantastic, and the Alien Albuquerque, New Mexico; July 29 - August 1, 2022 http://www.mythsoc.org/mythcon/mythcon-52.htm Abstract Analyzes what makes a fantasy “in the Tolkien tradition” and applies this definition ot a number of contemporary fantasy authors, including Ursula Le Guin, Richard Adams, Lloyd Alexander, and Stephen R. Donaldson. Additional Keywords Fantasy—Characteristics; Fantasy literature—Influence of J.R.R. olkien;T Tolkien, J.R.R.—Influence on fantasy literature This article is available in Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R.