Professional Attire,” Tive Attributes Mentioned Above, the Specialties

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

500 Years of Filipina Fashion

500 YEARS OF FILIPINA FASHION 2020 Asian Pacific Heritage Month 500 Years of Filipina Fashion By: Charity Bagatsing Doyl Research for this presentation includes: The Boxer Codex Emma Helen Blair’s The Philippine Islands 1493-1898 William Henry Scott’s Barangay Philippine Folklife Museum Foundation The Henry Otley Beyer Library Collection Thank You Dean Cameron, DaShond Bedford and Spokane Public Library. They do not however on this account go naked, they wear well made collarless robes which reach the ankles and are of cotton bordered with colors. When they are mourning, these robes are white. They take off this robes in their houses, and in places where garments are unnecessary. But everywhere and always they are very attentive to cover their persons with great care and modesty. Wherein they are superior to other nations, especially to the Chinese.” Father Chirino - Relacion de las Islas Filipinas 1602 One of the earliest records of Philippine fashions comes from the 16th century manuscript known as the Boxer Codex. 15th century Filipinos were described to wear stylish and lavishly beaded clothing from only the best and most expensive materials available at that time. In 1591, the Chinese merchants sold over 200,000 robes of cotton and silk up and down the islands. This shopping spree caused such an alarm to the Spanish regime because chiefs and slaves wore the same extravagant silk and lavishly beaded outfits, making it impossible to judge their rank from their dress. Another concern was the exorbitant amount of money Filipinos spent on their clothes, which the colonizers maintained should go to the Spanish treasury instead of the pockets of the Chinese traders. -

BELT RAILWAY of CHICAGO Special Instructions

BELT RAILWAY OF CHICAGO Special Instructions General Code Operating Rules 5th Edition Applies Maximum Speed A “Dimensional Load” is any load with a width of 11 Maximum speed permitted on BRC is 25 MPH feet 0 inches to 11 feet 6 inches as noted on the unless otherwise restricted. train consist. If a train has a dimensional load, the Conductor must advise the Dispatcher prior to Maximum speed must be maintained to the extent moving the train. possible, consistent with safety and efficiency. Crew members are responsible for knowing, maintaining, If a conductor has a dimensional load and has and not exceeding maximum speed for their train. received “pink message” notification of an Unnecessary delays must be avoided. excessive dimension load on another train that their Chicago Operating Rules Association (CORA) train may meet or pass, the conductor must notify Operating Guide the train dispatcher before moving the train. Employees operating in the Chicago Terminal District are required to have a current copy of the The Conductor must notify other crew members of CORA guide available for reference while on duty. the presence of both excessive dimension loads BRC Rules govern except as modified in the and dimensional loads before movement. CORA. 1.37 Maximum Gross Weight Limit 1.36 Shipments of Excessive Height / Width Maximum gross weight limitation is 143 Tons. The following classes of equipment are covered by Work equipment, cars, or platforms (other than 6 instructions from the BRC Clearance Bureau via a axle passenger cars and 6 axle locomotive cranes) “Pink Message” authority: with a gross weight greater than the route’s approved limit must not be moved over structures • Excessive dimensional loads unless authorized by the Engineering Department • Shipments including idler cars or cleared by clearance Bureau. -

Fashion Outfit Generation for E-Commerce Elaine M

Fashion Outfit Generation for E-commerce Elaine M. Bettaney Stephen R. Hardwick ASOS.com ASOS.com London, UK London, UK [email protected] [email protected] Odysseas Zisimopoulos Benjamin Paul Chamberlain ASOS.com ASOS.com London, UK London, UK [email protected] [email protected] ABSTRACT Combining items of clothing into an outfit is a major task in fashion retail. Recommending sets of items that are compatible with a particular seed item is useful for providing users with guidance and inspiration, but is currently a manual process that requires expert stylists and is therefore not scalable or easy to personalise. We use a multilayer neural network fed by visual and textual features to learn embeddings of items in a latent style space such that compatible items of different types are embedded close to one another. We train our model using the ASOS outfits dataset, which consists of a large number of outfits created by professional stylists and which we release to the research community. Our model shows strong performance in an offline outfit compatibility prediction task. We use our model to generate outfits and for the first time in this field perform an AB test, comparing our generated outfits to those produced by a baseline model which matches appropriate product types but uses no information on style. Users approved of outfits generated by our model 21% and 34% more frequently than those generated by the baseline model for womenswear and menswear respectively. KEYWORDS Representation learning, fashion, multi-modal deep learning 1 INTRODUCTION User needs based around outfits include answering questions such as "What trousers will go with this shirt?", "What can I wear to a Figure 1: An ASOS fashion product together with associated party?" or "Which items should I add to my wardrobe for summer?". -

Dictionary of United States Army Terms (Short Title: AD)

Army Regulation 310–25 Military Publications Dictionary of United States Army Terms (Short Title: AD) Headquarters Department of the Army Washington, DC 15 October 1983 UNCLASSIFIED SUMMARY of CHANGE AR 310–25 Dictionary of United States Army Terms (Short Title: AD) This change-- o Adds new terms and definitions. o Updates terms appearing in the former edition. o Deletes terms that are obsolete or those that appear in the DOD Dictionary of Military and Associated Terms, JCS Pub 1. This regulation supplements JCS Pub 1, so terms that appear in that publication are available for Army-wide use. Headquarters *Army Regulation 310–25 Department of the Army Washington, DC 15 October 1983 Effective 15 October 1986 Military Publications Dictionary of United States Army Terms (Short Title: AD) in JCS Pub 1. This revision updates the au- will destroy interim changes on their expira- thority on international standardization of ter- tion dates unless sooner superseded or re- m i n o l o g y a n d i n t r o d u c e s n e w a n d r e v i s e d scinded. terms in paragraph 10. S u g g e s t e d I m p r o v e m e n t s . T h e p r o p o - Applicability. This regulation applies to the nent agency of this regulation is the Assistant Active Army, the Army National Guard, and Chief of Staff for Information Management. the U.S. Army Reserve. It applies to all pro- Users are invited to send comments and sug- ponent agencies and users of Army publica- g e s t e d i m p r o v e m e n t s o n D A F o r m 2 0 2 8 tions. -

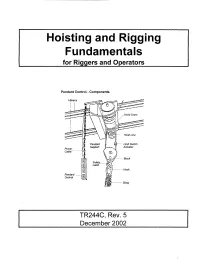

Hoisting & Rigging Fundamentals

Hoisting and Rigging Fundamentals for Riaaers and ODerators Pendant Control - Components TR244C, Rev. 5 December 2002 TR244C Rev . 5 TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ............................................................ ii HOISTING AND RIGGING OBJECTIVES ......................................... 1 WIRE ROPE SLINGS ......................................................... 2 SYNTHETIC WEBBING SLINGS ............................................... IO CHAINSLINGS ............................................................ 14 METAL MESH SLINGS ...................................................... 18 SPREADER BEAMS ........................................................ 19 RIGGING HARDWARE ...................................................... 22 INSPECTION TAG .......................................................... 39 CRITICAL LIFTS ........................................................... 40 GENERAL HOISTING AND RIGGING PRACTICES ................................ 44 HANDSIGNALS ............................................................ 64 INCIDENTAL HOISTING OPERATOR OBJECTIVES ............................... 68 HOISTS .................................................................. 69 OVERHEAD AND GANTRY CRANES ........................................... 71 MOBILECRANES .......................................................... 77 APPENDIX ................................................................ 81 TC:0007224.01 i TR244C Rev. 5 INTRODUCTION HOISTING AND RIGGING PROGRAM Safety should be the first priority when performing -

Complete Travel Packing Checklist

Complete Travel Packing Checklist Destination: ............................. Number of Days/Nights: ............................. Weather: ............................. Essentials: Toiletries: Clothing: Travel Documents: Toothbrush & Toothpaste Casual Tops Photo ID / Driver’s License Body Wash / Soap Dress Tops Passport / Visa Facewash T-shirts Boarding Passes Deodorant Jeans (printed or electronic) Eye drops / Contact Solution Casual Pants Confirmation Receipts Shampoo & Conditioner Dress Pants (printed or electronic) (hotel, train, Hand / Body Lotion Shorts bus, rental car, event tickets) Dresses Emergency Docs Health & Beauty: Skirts (health insurance card, allergy list, Blazers & Suit Coats emergency contact) Basic Medications Ties & Pocket Squares Funds: (headache, allergy, stomach upset, Sweaters motion sickness, sleep aid) Outerwear (Coat/Jacket) Wallet Basic First Aid Activewear Credit Cards (band-aids, antibiotic ointment) Cash Vitamins Swimwear & Cover-Ups Pajamas & Loungewear Other: Sunscreen Shaving Items Underwear Cell Phone + Charger Hair Product Socks Keys (gel, mousse, cream, paste) Bras Glasses / Contacts Hair Tools Tights / Hosiery Rx Medication (blowdryer, straightener) Brush, Hair Ties, Bobby Pins Shoes: Personal Comfort: Makeup Perfume / Cologne Tennis Shoes Neck Pillow Feminine Care Items Dress Shoes / Heels Warm Layer (shawl, sweater) Tweezers Flats Warm Socks Q-tips, Tissues, Cotton Sandals Eye Mask Rounds Boots Headphones / Earplugs Nail Polish Specialty Book / Magazines (water shoes, cycling shoes, hiking Water -

Mining Fashion Outfit Composition Using an End-To-End Deep Learning Approach on Set Data

1 Mining Fashion Outfit Composition Using An End-to-End Deep Learning Approach on Set Data Yuncheng Li, LiangLiang Cao, Jiang Zhu, Jiebo Luo, Fellow, IEEE Abstract—Composing fashion outfits involves deep under- standing of fashion standards while incorporating creativity for choosing multiple fashion items (e.g., Jewelry, Bag, Pants, Dress). In fashion websites, popular or high-quality fashion outfits are usually designed by fashion experts and followed by large audiences. In this paper, we propose a machine learning system to compose fashion outfits automatically. The core of the proposed automatic composition system is to score fashion outfit candidates based on the appearances and meta-data. We propose to leverage outfit popularity on fashion oriented websites to supervise the scoring component. The scoring component is a multi-modal multi-instance deep learning system that evaluates instance aesthetics and set compatibility simultaneously. In order to train and evaluate the proposed composition system, we have collected a large scale fashion outfit dataset with 195K outfits and 368K fashion items from Polyvore. Although the fashion outfit scoring and composition is rather challenging, we have achieved an AUC of 85% for the scoring component, and an accuracy of 77% for a constrained composition task. Fig. 1: An example showing the challenging of fashion outfit Index Terms—Multimedia computing, Multi-layer neural net- composition. Normally one would not pair a fancy dress (as in work, Big data applications, Multi-layer neural network the left) with the casual backpack (as in the bottom right) but once you add in the shoes (as in the top right), it completes I. -

Dress of the Oregon Trail Emigrants: 1843 to 1855 Maria Barbara Mcmartin Iowa State University

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Retrospective Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 1977 Dress of the Oregon Trail emigrants: 1843 to 1855 Maria Barbara McMartin Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd Part of the American Material Culture Commons, Fashion Design Commons, Home Economics Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation McMartin, Maria Barbara, "Dress of the Oregon Trail emigrants: 1843 to 1855" (1977). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 16715. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/16715 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Dress of the Oregon Trail emigrants: 1843 to 1855 by Maria Barbara McMartin A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Partial Fulfillment of The Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE Major: Textiles and Clothing Signatures have been redacted for privacy Iowa State University Ames, Iowa 1977 ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page INTRODUCTION 1 FACTORS CONTRIBUTING TO THE MIGRATION TO OREGON 5 THE OREGON TRAIL 13 PREPARATIONS FOR THE JOURNEY TO OREGON 19 CLOTHING AND ACCESSORIES OF EMIGRATING FAMILIES 28 THE EFFECT OF TRAIL LIFE ON CLOTHING 57 CARING FOR CLOTHING ALONG THE TRAIL 61 CONCLUSIONS AND SUMMARY 65 SOURCES CITED 68 ADDITIONAL MANUSCRIPTS CONSULTED 73 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS 76 iii LIST OF FIGURES Page Figure 1. Model of Conestoga-type wagon on display in Oregon Historical Society exhibit 22 Figure 2. -

Victorian - Edwardian - WW I

Victorian - Edwardian - WW I AG 1124 $25.00 AG 1335 $36.50 1875 Plain & Plaid De Beget AG 1123 $28.50 1873 Blue Linen & Percale Dress 1875 Plain & Plaid Camel's Hair Dress Sizes: 34 Bust - 25 Waist Only Dress Sizes: 34 Bust - 24 Waist Only This brown De Beget dress Sizes: 38 Bust - 26 Waist Only Dress consists of an overskirt, consists of skirt, overskirt, and This dress consists of skirt, underskirt, vest, and Basque. waist. overskirt, and waist. AG 1132 $26.75 AG 1009 $19.50 1878 Scotch Plaid Dress 1878 Blue Gros Grain AG 1010 $19.50 1878 Black Faille House Dress Sizes: 38 Bust - 26 Waist Only Reception Dress Sizes: 36 Bust - 24 Waist Only This dress was made of blue and Sizes: 36 Bust - 22 Waist Only This dress was made of black green scotch plaid, and is The dress was made of light blue composed of a skirt, overskirt, gros grain and consists of a skirt faille and consists of a skirt and Basque. The skirt is and waist. The trimming is of and bodice. The sleeves are black velvet with piping on the trimmed with a border, bows, trimmed on the bottom a side pleated ruffle. jacket puffs, and ruffles of crepe plissé. AG 1021 $28.00 . 1878 Figured Bourette AG 1133 $24.00 Reception Dress 1878 Mousseline des Indies PA 303 $31.00 Sizes: 32 Bust - 22 Waist Only Wrapper 1882-1885 Wedding Gown This dress was made of fawn and Sizes: 38 Bust - 26 Waist Only Sizes: Multisized 10-16 brown colored figured bourette, This morning wrapper was made 1882-1885 Wedding Gown the skirt is trimmed with a side of blue Mousseline de Indies with Optional and cathedral train. -

Spring / Summer 2020 Belvest.Com

BELVEST.COM SPRING / SUMMER 2020 You are moving fast. You have a train to catch, another airport to get to. Backpack slung over your back; nothing can slow you down. The city is moving fast and you don’t want to be left behind. Once you reach your destination, you live every moment to the fullest, savoring each and every second until you prepare to leave again. Like any man that makes the world his dwelling, never stopping in one place, you refute past rules and labels. You conform only to the unique rhythm and language of your life. You are curious, and love discovering anything new and exclusive, because in the act of pursuit lies the true joy of every journey. And it is when you eschew the ordinary that we welcome you with open arms into our new showroom: a treasure trove in the heart of Milan, where you can discover the Spring/Summer 2020 collection, designed to accompany you wherever you decide to roam. Technical and ultranatural fabrics, relaxed shapes and oversize details follow your every move like a second skin. Because style isn’t a set of rules to be followed, rather a set of lines to be crossed. Diverge from the beaten track, trace your own path and pen your own story. BELVEST 4 BELVEST 6 7 SPRING / SUMMER 2020 BELVEST 8 BELVEST 10 11 SPRING / SUMMER 2020 BELVEST 13 SPRING / SUMMER 2020 14BELVEST 14 15 SPRING / SUMMER 2020 BELVEST 16 17 SPRING / SUMMER 2020 BELVEST 18 19 SPRING / SUMMER 2020 BELVEST 20 22 23 SPRING / SUMMER 2020 BELVEST 24 25 SPRING / SUMMER 2020 BELVEST 26 BELVEST 28 BELVEST 30 31 SPRING / SUMMER 2020 BELVEST 32 33 SPRING / SUMMER 2020 BELVEST 34 35 SPRING / SUMMER 2020 BELVEST 36 37 SPRING / SUMMER 2020 2 T0021630001 Single-breasted wool and polyamide jacket. -

Amtrak Service Standards Manual for Train Service and On-Board Service Employees, Version 6, 2011

Description of document: Amtrak Service Standards Manual for Train Service and On-Board Service Employees, Version 6, 2011 Requested date: 07-May-2011 Released date: 28-July-2011 Posted date: 01-August-2011 Date of document: Effective date: April 30, 2011 Source of document: Amtrak FOIA Office 60 Massachusetts Avenue, NE Washington, D.C. 20002 Fax: 202-906-3285 Email: [email protected] The governmentattic.org web site (“the site”) is noncommercial and free to the public. The site and materials made available on the site, such as this file, are for reference only. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals have made every effort to make this information as complete and as accurate as possible, however, there may be mistakes and omissions, both typographical and in content. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals shall have neither liability nor responsibility to any person or entity with respect to any loss or damage caused, or alleged to have been caused, directly or indirectly, by the information provided on the governmentattic.org web site or in this file. The public records published on the site were obtained from government agencies using proper legal channels. Each document is identified as to the source. Any concerns about the contents of the site should be directed to the agency originating the document in question. GovernmentAttic.org is not responsible for the contents of documents published on the website. NATIONAL RAilROAD PASSENGER CORPORATION GO Massachusetts Avenue, NE, Washington, DC 20002 VIAE-MAIL July 28, 20 II Re: Freedom oflnformation Act Request We are further responding to your May 7, 2011 request for information made under the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA), which was received by Amtrak's FOIA Office on May 13, 2011. -

Welcome to the Fashion Costume Gallery

Welcome to the Fashion Costume Gallery Costume History Timeline click on thumbnails for larger images and information 1890 1900 1910 1950 1960 1970 1980 Wedding Ensemble c. 1898 This dress was donated to CSUS by Professor Emeritus, Jeline Ware. Her grandmother wore the ensemble for her wedding in 1898. In 1924 the dress was worn by her mother for her wedding, and then by her mother's youngest sister for her wedding in 1940. The dress was worn again by Jeline Ware's mother for her 25 th wedding anniversary in 1949. This two piece ensemble contains a fitted, fully boned, bodice with a long full skirt with train. The ensemble is made out of light weight wool with silk ribbon accents. Silk pleated ribbon decorates the hem of the skirt. It also decorates the bodice and sleeves in beautiful scroll patterns. The bust insert, which is made of chiffon, was added in 1949. The ensemble is finished off by a wide silk belt with a bow. This piece embodies many of the characteristics of clothing from the era. During the 1890s, two piece dresses with boned detail bodices were popular. During this period skirts were full, but lacked the bustles that had been so popular in the previous decade. In the latter years of the 1890s sleeves became narrow compared to the large puffed sleeves that had been popular during the first part of the decade. -Rachel Young Lace Undergarment c. 1903 Undergarments such as this white lace combination bodice and drawers were worn by women and girls under a corset throughout the late 1890's and into the early twentieth century.