The Provhet Muhammad in Christian Theological Perspective

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Course Syllabus EMT 3101/6101HF Biography and Thought: the Life of Muhammad Emmanuel College Toronto School of Theology Fall 2017

Course Syllabus EMT 3101/6101HF Biography and Thought: The Life of Muhammad Emmanuel College Toronto School of Theology Fall 2017 Instructor Information Instructor: Nevin Reda Office Location: EM 215 Telephone: Office – (416) 978-000 E-mail: [email protected] Office Hours: Wednesdays, 11:00 am – 12:00 pm or by appointment Course Identification Course Number: EMT3101/6101HF Course Format: In-class Course Name: Biography and Thought: The Life of Muhammad Course Location: EM 302 Class Times: Tuesdays 14:00 pm – 16:00 pm Prerequisites: None Course Description This seminar studies the life of the Prophet Muhammad as it is presented in the earliest biographical and historical Muslim accounts. It introduces the sira and hadith literatures, in addition to classical and modern critical methods used to determine their authenticity and historical reliability. Topics include the first revelations, emigration from Mecca, the Constitution of Medina, and succession to Muhammad’s leadership. Students will learn about Muslim concepts of prophethood, the significance of the prophet in the legal-ethical and mystical traditions, and women in hadith scholarship. They will study the life of Muhammad and relate it to his spiritual as well as temporal experience to explore modern-day concerns. Class participation: 15%, Minor Research Paper: 35 %, Major research paper: 50 %. Course Resources Required Course Texts/Bibliography ‘Abd al-Malik ibn Hisham, The life of Muhammad: a translation of Ishāq's Sīrat rasūl Allāh, with introduction and notes by A. Guillaume (London: Oxford University Press, 1955). Jonathan Brown, Hadith: Muhammad's Legacy in the Medieval and Modern World (Richmond: Oneworld, 2009). -

An Analytical Study of Women-Related Verses of S¯Ura An-Nisa

Gunawan Adnan Women and The Glorious QurÞÁn: An Analytical Study of Women-RelatedVerses of SÙra An-NisaÞ erschienen in der Reihe der Universitätsdrucke des Universitätsverlages Göttingen 2004 Gunawan Adnan Women and The Glorious QurÞÁn: An Analytical Study of Women- RelatedVerses of SÙra An-NisaÞ Universitätsdrucke Göttingen 2004 Die Deutsche Bibliothek – CIP-Einheitsaufnahme Ein Titelsatz für diese Publikation ist bei der Deutschen Bibliothek erhältlich. © Alle Rechte vorbehalten, Universitätsverlag Göttingen 2004 ISBN 3-930457-50-4 Respectfully dedicated to My honorable parents ...who gave me a wonderful world. To my beloved wife, son and daughter ...who make my world beautiful and meaningful as well. i Acknowledgements All praises be to AllÁh for His blessing and granting me the health, strength, ability and time to finish the Doctoral Program leading to this book on the right time. I am indebted to several persons and institutions that made it possible for this study to be undertaken. My greatest intellectual debt goes to my academic supervisor, Doktorvater, Prof. Tilman Nagel for his invaluable advice, guidance, patience and constructive criticism throughout the various stages in the preparation of this dissertation. My special thanks go to Prof. Brigitta Benzing and Prof. Heide Inhetveen whose interests, comments and guidance were of invaluable assistance. The Seminar for Arabic of Georg-August University of Göttingen with its international reputation has enabled me to enjoy a very favorable environment to expand my insights and experiences especially in the themes of Islamic studies, literature, phylosophy, philology and other oriental studies. My thanks are due to Dr. Abdul RazzÁq Weiss who provided substantial advice and constructive criticism for the perfection of this dissertation. -

RSOC 154. Winter 2016 Jesus in Islam and Christianity

RSOC 154. Winter 2016 Jesus in Islam and Christianity: A Comparison of Christologies Instructor: Professor D. Pinault Tuesday-Thursday 2.00-3.40pm Classroom: Kenna 310 Prof. Pinault’s Office: Kenna 323 I Telephone: 408-554-6987 Email: [email protected] Office hours: Tuesday & Thursday 4.15- 5.15pm & by appointment NB: This is an RTC level 3 course. Course prerequisites: Introductory- and intermediate-level courses in Religious Studies. RSOC 154. Winter 2016. Jesus in Islam & Christianity. Syllabus. 1 | Page Course description. A prefatory comment: Too often, in my experience, Muslim-Christian dialogue, motivated by a praiseworthy and entirely understandable desire to minimize violence and destructive prejudice, tends to emphasize whatever the two religions share in common. Interfaith gatherings motivated by such concerns sometimes neglect points of substantive difference between the faiths, especially with regard to Islamic and Christian understandings of Jesus. This is regrettable, and certainly not the approach I propose to attempt as you and I undertake this course. Instead, while acknowledging certain similarities between Islam and Christianity, and giving attention to the highly important commonalities they share with Judaism (all three faiths, it should be noted, are given a special shared status in Islamic theology as al-adyan al- samawiyah, “the heavenly religions”), I nonetheless will emphasize the radical differences between Islam and Christianity in their understandings of Jesus. I do this for a specific reason. I believe that highlighting only the similarities between these traditions does a disservice to both, whereas a critical yet sympathetic comparison of Islamic and Christian Christologies allows us to appreciate the distinctive spiritual treasures available in each religion. -

Muhammad at the Museum: Or, Why the Prophet Is Not Present

religions Article Muhammad at the Museum: Or, Why the Prophet Is Not Present Klas Grinell Department of Literature, History of Ideas, and Religion, University of Gothenburg, SE405 30 Göteborg, Sweden; [email protected] Received: 30 October 2019; Accepted: 5 December 2019; Published: 10 December 2019 Abstract: This article analyses museum responses to the contemporary tensions and violence in response to images of Muhammad, from The Satanic Verses to Charlie Hebdo. How does this socio-political frame effect the Metropolitan Museum of Art in NY, the V&A and British Museum in London, and the Louvre in Paris? Different genres of museums and histories of collections in part explain differences in approaches to representations of Muhammad. The theological groundings for a possible ban on prophetic depictions is charted, as well as the widespread Islamic practices of making visual representations of the Prophet. It is argued that museological framings of the religiosity of Muslims become skewed when the veneration of the Prophet is not represented. Keywords: museums; Islam; Muhammad; Islamicate cultural heritage; images; exhibitions; Islamic art; collection management 1. Introduction One seldom comes across the Prophet Muhammad in museum exhibitions of Islamicate heritage. The aim of this article is to analyze the framings of this absence, and to discuss how it affects the representations of Islam given in museums. Critical frame analysis will be used to analyze empirical material consisting of the displays in museums with major exhibits of Islamicate material culture in the US, Germany, France, the UK, Turkey and Iran in 2015–2018. The contemporary socio-political frame will be uncovered from media coverage of conflicts around non-Muslim representations of Muhammad from the Rushdie affair to the present.1 To understand different possible Islamic framings of representations of the Prophet, Islamic theological and devotional traditions will be consulted. -

Boston College Encore Access Islam 101 Transcript of Part 2

Boston College SCHOOL OF THEOLOGY AND MINISTRY CONTINUING EDUCATION Encore Access Islam 101 Transcript of Part 2 What Muslims believe about the Prophet Muhammad presented on March 5, 2015 by Dr. Natana DeLong-Bas Who is Prophet Muhammad? Before anybody worries that anybody's going to be offended by the picture that's there, this is from a Persian miniature. And this is one of the ways in which the prophet has been depicted in artwork, historically. You'll notice that his face is not shown. He's shown wearing a veil so that we don't have to worry about anybody potentially worshipping Muhammad rather than God. Muslims will always tell you that Muhammad was strictly a human being. He was not a divine figure. Nevertheless, they believe that he is the most perfect human being who has ever lived, because he best represents what it means to live out the teachings of the Qur’an. As one of my Muslim friends has said, “Muslim reference is to Muhammad, Muslim reverence is to God.” Muslims spend a lot of time studying the prophet's example called the sunna, which are recorded in literature called the hadith. And these are records of sayings and doings of the prophet. Sometimes, you only have one hadith that will talk about in issue, but oftentimes, you'll have hundreds, if not thousands, about the same incident. And the reason for that is that Muhammad didn't spend a lot of time by himself. He always had an entourage of people with him. He had friends and companions, kind of like Jesus and his disciples, who would follow him around. -

NL-April-05Th-2019.Pdf

PRAYER TIMINGS Effective 04/06 MCA NOOR Fajr 5:40 5:50 Dhuhr 1:30 1:30 Asr 5:15 6:00 Maghrib Sunset Sunset Isha 9:10 9:10 Juma1 12:15 12:15 Juma2 1:30 1:30 Newsletter Published Weekly by the Muslim Community Association of San Francisco Bay Area Rajab 29, 1440 April 5, 2019 AL-QURAN Exalted is He who took His Servant by night from al-Masjid al-Haram to al-Masjid al- Aqsa, whose surroundings We have blessed, to show him of Our signs. Indeed, He is the Hearing, the Seeing. And We gave Moses the Scripture and made it a guidance for the Children of Israel that you not take other than Me as Disposer of affairs, O descendants of those We carried [in the ship] with Noah. Indeed, he was a grateful servant. QURAN 17:2-4 HADITH Abu Huraira reported Allah’s Messenger (peace be upon him) as saying: You would find people like those of mine, the good amongst you in the Days of Ignorance would be good amongst you in the days of Islam, provided they have an understanding of it and you will find good amongst people the persons who would be averse to position of authority until it is thrust upon them, and you will find the worst amongst persons one who has double face. He comes with one face to them and with the other face to the others. Sahih Muslim, Book 44, Hadith 283 Join the MCA Mailing List and Stay Connected MCA Board’s Corner Date: Tuesday March 26, 2019 The Executive Board met on March 26, 2019. -

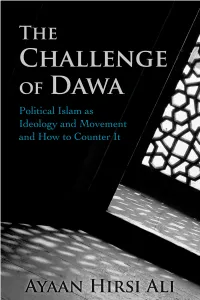

Ayaan Hirsi Ali Research Fellow, Hoover Institution, Stanford University

Testimony before the Committee on Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs Of the United States Senate On “Ideology and Terror: Understanding the Tools, Tactics, and Techniques of Violent Extremism” By Ayaan Hirsi Ali Research Fellow, Hoover Institution, Stanford University Wednesday, June 14, 2017 10 AM Dirksen Senate Office Building 342 P. 1 Thank you, Chairman Johnson and members of the Committee on Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs. I am Ayaan Hirsi Ali, a Research Fellow at the Hoover Institution, Stanford University, and founder of the AHA Foundation. It is a privilege to speak with you today about the ideology underlying Islamist terrorism, and the connection between non-violent Islamist extremism and violent Islamist extremism. My testimony is based, with slight modifications, on my recently published monograph The Challenge of Dawa: Political Islam as Ideology and Movement and How to Counter It (Hoover, 2017). In the time since my monograph was published earlier this year, a series of attacks in Manchester and London have led British Prime Minister Theresa May to call for tackling the ideology underlying Islamist terrorism.1 According to May, a series of “difficult and often embarrassing conversations” will be required in order to tackle extremism in the United Kingdom. In France, under the state of emergency imposed after the Charlie Hebdo massacre, authorities have closed twenty mosques and prayer halls for extremist preaching.2 In mid-November of 2016, German authorities in sixty cities searched more than 190 mosques, apartments, and of offices connected with “True Religion,” a radical Islamist group accused of radicalizing German Muslims and of recruiting for the Islamic State.3 These stringent measures follow years of relative inaction. -

ʿalī Ibn Abī Ṭālib: an Investigatory Reading In

International Journal of Asian History, Culture and Tradition Vol.4, No.3, pp.1-7, July 2017 ___Published by European Centre for Research Training and Development UK (www.eajournals.org) ʿALĪ IBN ABĪ ṬĀLIB: AN INVESTIGATORY READING IN THE EMPLOYMENT OF HIS CHILDHOOD IN THE MECCAN PERIOD IN THE SOURCES OF THE SHĪʿITE HERITAGE Sāleḥ ʿAbbūd Emek Yezreel College ABSTRACT: The classical Shīʿite sources employed ʿAlī bin Abī Ṭālib's childhood to the benefit of the Imāmiyya Shīʿite doctrine that depends on Ali's character to a great extent and looks at him as a focal imam with incomparable centrality and states that no one is equal to him except Prophet Moḥammad. The Shīʿite sources tried on several occasions to highlight certain events that are related to the personality of Alī bin Abī Ṭālib when he was still a child in Mecca in order to raise his position and status and distinction from other Moslems by attributing to him outstanding traits and virtues that justify their view about his being the legitimate Caliph and the most important imam in the series of the twelve imams in the Shīʿite doctrine. The Shīʿa exploited some events that are related to Ali's childhood in order to concentrate on his intimate relationship with Prophet Moḥammad and his proximity to him, which was intended to prepare for talking about his right to be the caliph after the Prophet's death. KEYWORDS: Meccan stage, Shīʿa heritage, imāmiyyah, caliph, Prophet, centrality, traits. INTRODUCTION The pages of Islamic history and the great heritage that Moslem scholars and classical classifiers left during the first five centuries of Hegira deal with lots of Islamic outstanding personalities who left prominent marks on the history of the Islamic world. -

The Challenge of Dawa Political Islam As Ideology and Movement and How to Counter It

The Challenge of Dawa Political Islam as Ideology and Movement and How to Counter It Ayaan Hirsi Ali HOOVER INSTITUTION PRESS STANFORD UNIVERSITY | STANFORD, CALIFORNIA With its eminent scholars and world-renowned library and archives, the Hoover Institution seeks to improve the human condition by advancing ideas that promote economic opportunity and prosperity, while securing and safeguarding peace for America and all mankind. The views expressed in its publications are entirely those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the staff, officers, or Board of Overseers of the Hoover Institution. www.hoover.org Hoover Institution Press Publication Hoover Institution at Leland Stanford Junior University, Stanford, California 94305-6010 Copyright © 2017 by the Board of Trustees of the Leland Stanford Junior University All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without written permission of the publisher and copyright holders. Efforts have been made to locate the original sources, determine the current rights holders, and, if needed, obtain reproduction permissions. On verification of any such claims to rights in the articles reproduced in this book, any required corrections or clarifications will be made in subsequent printings/editions. Hoover Institution Press assumes no responsibility for the persistence or accuracy of URLs for external or third-party Internet websites referred to in this publication, and does not guarantee that any content on such websites is, or will remain, accurate or appropriate. First printing 2017 23 22 21 20 19 18 17 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Manufactured in the United States of America The paper used in this publication meets the minimum Requirements of the American National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992. -

The Qur'anic Jesus: a Study of Parallels with Non-Biblical Texts

Western Michigan University ScholarWorks at WMU Dissertations Graduate College 8-2013 The Qur'anic Jesus: A Study of Parallels with Non-Biblical Texts Brian C. Bradford Western Michigan University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/dissertations Part of the History of Religion Commons, and the History of Religions of Western Origin Commons Recommended Citation Bradford, Brian C., "The Qur'anic Jesus: A Study of Parallels with Non-Biblical Texts" (2013). Dissertations. 190. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/dissertations/190 This Dissertation-Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate College at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE QUR’ANIC JESUS: A STUDY OF PARALLELS WITH NON-BIBLICAL TEXTS by Brian C. Bradford A dissertation submitted to the Graduate College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of History Western Michigan University August 2013 Doctoral Committee: Paul Maier, Ph.D., Chair Howard Dooley, Ph.D. Timothy McGrew, Ph.D. THE QUR’ANIC JESUS: A STUDY OF PARALLELS WITH NON-BIBLICAL TEXTS Brian C. Bradford, Ph.D. Western Michigan University, 2013 This study examines which texts and religious communities existed that could well have contributed to Muhammad’s understanding of Jesus. The most important finding is that the Qur’anic verses mentioning Jesus’ birth, certain miracles, and his crucifixion bear close resemblance to sectarian texts dating as early as the second century. -

Introductory Notes on the Religion Oflslam

Introductory Notes on the Religion oflslam Thomas F. Michel, S.J. Fr. Thomas Michel was born in St. Louis, Missouri, educated in Catholic schools and seminary, and ordained a priest for the Archdiocese ofSt. Louis in 1967. 1n 1969, after a year as a missionary in Indonesia, he entered.the Society ofJesus. He was sent to study Arabic and Islam to Lebanon and Egypt, completing a Ph.D at the University ofChicago in 1978. In 1981, he began serving at the Vatican's Pontifical Council for Interreligious Dialogue, and then from 1996 to 2008, he served as Secretary for Interreligious Dialogue for the Superior General ofthe Jesuits. He is currently on sabbatical as an international fellow at Woodstock Theological Center, Georgetown University. These notes are taken from a handbook for teaching Islam that Fr. Michel had developed for use in various institutes and courses that he has been called upon to teach. We are grateful for his generosity in allowing us to use this for our instruction. MUHAMMAD: THE PROPHET OF ISLAM Muhammad's early life before his prophetic call Muhammad was born about the year 570 in Mecca, near the west coast of central Arabia. Due to continuing wars between the Byzantine and Persian empires, the normal trade routes between India and the Mediterranean were disrupted, which proved to be a boon for towns like Mecca along the Arabian caravan route. Mecca was more prosperous than its neighbors because of the presence of the Ka'ba, a pagan shrine for all Arabian tribes, and hence a haram where killing was not permitted. -

The Life of Muhammad As Viewed by the Early Muslims

STUDIES IN LATE ANTIQUITY AND EARLY ISLAM 5 THE EYE OF THE BEHOLDER THE LIFE OF MUHAMMAD AS VIEWED BY THE EARLY MUSLIMS A T e x t u a l A n a l y s i s STUDIES IN LATE ANTIQUITY AND EARLY ISLAM 5 THE EYE OF THE BEHOLDER THE LIFE OF MUHAMMAD AS VIEWED BY THE EARLY MUSLIMS A T e x t u a l A n a l y s i s U R I R U B IN THE DARWIN PRESS, INC. PRINCETON, NEW JERSEY 1995 Copyright © 1995 by THE DARWIN PRESS, INC., Princeton, NJ 08543. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval sys tem, or transmitted, in any form, by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations in critical articles or reviews. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Rubin, Uri, 1944-. The eye of the beholder : the life of Muhammad as viewed by the early Muslims : a textual analysis / Uri Rubin. p. cm. - (Studies in late antiquity and early Islam : 5) Includes bibliographical references (to p. ) and index. ISBN 0-87850-110-X : $27.50 1. Muhammad, Prophet, d. 632-Biography-History and criticism. I. Title. II. Series. BP75.3.R83 1995 297’.63-dc20 94-49175 CIP The paper in this book is acid-free neutral pH stock and meets the guidelines for permanence and durability of the Committee on Production Guidelines for Book Longevity of the Council on Library Resources.