Annual Progress Report Year 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Election Process of the Regional Representatives to the Parliament of the Democratic Republic of Azerbaijan

№ 20 ♦ УДК 342 DOI https://doi.org/10.32782/2663-6170/2020.20.7 THE ELECTION PROCESS OF THE REGIONAL REPRESENTATIVES TO THE PARLIAMENT OF THE DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF AZERBAIJAN ВИБОРЧИЙ ПРОЦЕС РЕГІОНАЛЬНИХ ПРЕДСТАВНИКІВ У ПАРЛАМЕНТ АЗЕРБАЙДЖАНСЬКОЇ ДЕМОКРАТИЧНОЇ РЕСПУБЛІКИ Malikli Nurlana, PhD Student of the Lankaran State University The mine goal of this article is to investigate the history of the creation of the Democratic Republic of Azerbaijan par- liament, laws on parliamentary elections, and the regional election process in parliament. In addition, an analysis of the law on elections to the Azerbaijan Assembly of Enterprises. The article covers the periods of 1918–1920. The presented article analyzes historical processes, carefully studied and studied the process of elections of regional representatives to the Parliament of the Democratic Republic of Azerbaijan. Realities are reflected in an objective approach. A comparative historical study of the election of regional representatives was carried out in the context of the creation of the parliament of the Democratic Republic of Azerbaijan and the holding of parliamentary elections. The scientific novelty of the article is to summarize the actions of the parliament of the first democratic republic of the Muslim East. Here, attention is drawn to the fact that before the formation of the parliament, the National Assembly, in which the highest executive power, trans- ferred its powers to the legislative body and announced the termination of its activities. It is noted that the Declaration of Independence of Azerbaijan made the Republic of Azerbaijan a democratic state. It is from this point of view that attention is drawn to the fact that the government of the Azerbaijan Democratic Republic had to complete the formation of institutions capable of creating a solid legislative base in a short time. -

Title of the Paper

Nabiyev et al.: Formation characteristics of the mudflow process in Azerbaijan and the division into districts of territory based on risk level (on the example of the Greater Caucasus) - 5275 - FORMATION CHARACTERISTICS OF THE MUDFLOW PROCESS IN AZERBAIJAN AND THE DIVISION INTO DISTRICTS OF TERRITORY BASED ON RISK LEVEL (ON THE EXAMPLE OF THE GREATER CAUCASUS) NABIYEV, G. – TARIKHAZER, S.* – KULIYEVA, S. – MARDANOV, I. – ALIYEVA, S. Institute of Geography Named After Acad. H. Aliyev, Azerbaijan National Academy of Sciences 115, av. H. Cavid, Baku, Azerbaijan (phone: +994-50-386-8667; fax: +994-12-539-6966) *Corresponding author e-mail: [email protected] (Received 25th Jan 2019; accepted 6th Mar 2019) Abstract. In Azerbaijani part of the Greater Caucasus, which has been intensively developed in recent years in order to exploit recreational resources. Based on the interpretation of the ASP within the Azerbaijani part of the Greater Caucasus based on the derived from the effect of mudflow processes (the amount of material taken out, the erosive effect of the flow on the valley, the accounting of the mudflows and the basin as a whole, and the prevailing types and classes of mudflows, the geomorphological conditions of formation and passage mudflows, and statistical data on past mudflows) on the actual and possible damage affecting the population from mudflows a map-scheme was drawn up according to five- point scale. On the scale there are zones with a high (once in two-three years, one strong mudflow is possible) - V, with an average (possibility for one strong mudflow every three-five years) - IV, with a weak (every five-ten years is possible 1 strong mudflow) - III, with potential mudflow hazard - II and where no mudflow processes are observed - I. -

Four Days Incommunicado at Secret Police - So Far

FORUM 18 NEWS SERVICE, Oslo, Norway http://www.forum18.org/ The right to believe, to worship and witness The right to change one's belief or religion The right to join together and express one's belief 16 April 2014 AZERBAIJAN: Four days incommunicado at secret police - so far By Felix Corley, Forum 18 News Service The NSM secret police has been holding two Muslims incommunicado since 12 April, including a man who offered his Baku home for a Muslim study session, Muslims who know them told Forum 18 News Service. Eldeniz Hajiyev and fellow Nursi reader Ismayil Mammadov were seized after an armed police raid on the meeting. Forum 18 was unable to reach anyone at the NSM secret police in Baku to find out where the men are being held and why. Nine others present were fined more than three months' average wages each. Fined the same day by the same court was a Shia Muslim theologian who had been teaching his faith in the same Baku district. Azerbaijan has tight government controls on exercising the right to freedom of religion or belief. Meetings for worship or religious education, or selling religious literature without state permission are banned and punishable. Four days after a 12 April armed police raid on Muslims studying the writings of the late Turkish Sunni Muslim theologian Said Nursi, the home owner Eldeniz Hajiyev and another person present Ismayil Mammadov are still being held incommunicado by the National Security Ministry (NSM) secret police, fellow Nursi readers told Forum 18 News Service from Azerbaijan's capital Baku. -

3.1 Demographic Trends and Labor Market Assessment

Addressing skills mismatch and informal employment in Azerbaijan Aimee Hampel-Milagrosa 1 and Jasmin Sibal 2 In the aftermath of the oil price shock of 2014, Azerbaijan launched an ambitious reform agenda that embedded the critical role of human capital in increased labor productivity, higher competitive capacity and sustainable economic growth. While this new reform strategy reinforces and expands the numerous education-system reforms implemented in the country since it gained independence in 1991, many challenges remain. Azerbaijan is among the lowest in Eastern Europe and Central Asia in terms of government spending on education, quality of secondary and vocational education and training, and enrolment in primary and tertiary education. The country also suffers from a pronounced skills mismatch and high levels of informal employment. This paper presents the most recent and comprehensive demographic trends and labor market assessment for Azerbaijan. Using national data, it traces origins of the skills gap, reviews the challenges in skills development and discusses early gains in the latest education reform agenda. The paper ends with recommendations that would strengthen the institutional set-up for education and skills development, including specific policy areas where Azerbaijan education policy could be refined. JEL codes: E24, J21, J24, J46, 3.1 Demographic Trends and Labor Market Assessment Azerbaijan’s 2016 Strategic Road Maps on the National Economy Perspective and Main Sectors of the Economy recognize that human capital plays a key role in increasing labour productivity, sustainable economic growth, higher competitive capacity in manufacturing and services, and the country’s integration into global markets. Numerous education-system reforms have been undertaken since the country’s independence in 1991. -

Turkic Toponyms of Eurasia BUDAG BUDAGOV

BUDAG BUDAGOV Turkic Toponyms of Eurasia BUDAG BUDAGOV Turkic Toponyms of Eurasia © “Elm” Publishing House, 1997 Sponsored by VELIYEV RUSTAM SALEH oglu T ranslated by ZAHID MAHAMMAD oglu AHMADOV Edited by FARHAD MAHAMMAD oglu MUSTAFAYEV Budagov B.A. Turkic Toponyms of Eurasia. - Baku “Elm”, 1997, -1 7 4 p. ISBN 5-8066-0757-7 The geographical toponyms preserved in the immense territories of Turkic nations are considered in this work. The author speaks about the parallels, twins of Azerbaijani toponyms distributed in Uzbekistan, Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan, Altay, the Ural, Western Si beria, Armenia, Iran, Turkey, the Crimea, Chinese Turkistan, etc. Be sides, the geographical names concerned to other Turkic language nations are elucidated in this book. 4602000000-533 В ------------------------- 655(07)-97 © “Elm” Publishing House, 1997 A NOTED SCIENTIST Budag Abdulali oglu Budagov was bom in 1928 at the village o f Chobankere, Zangibasar district (now Masis), Armenia. He graduated from the Yerevan Pedagogical School in 1947, the Azerbaijan State Pedagogical Institute (Baku) in 1951. In 1955 he was awarded his candidate and in 1967 doctor’s degree. In 1976 he was elected the corresponding-member and in 1989 full-member o f the Azerbaijan Academy o f Sciences. Budag Abdulali oglu is the author o f more than 500 scientific articles and 30 books. Researches on a number o f problems o f the geographical science such as geomorphology, toponymies, history o f geography, school geography, conservation o f nature, ecology have been carried out by academician B.A.Budagov. He makes a valuable contribution for popularization o f science. -

ORGANIC AGRICULTURE in AZERBAIJAN Current Status and Potentials for Future Development

ORGANIC AGRICULTURE ISBN 978-92-5-130100-5 IN AZERBAIJAN 978 9251 301005 Current status and potentials XXXX/1/12.17 for future development ORGANIC AGRICULTURE IN AZERBAIJAN Current status and potentials for future development Uygun AKSOY, İsmet BOZ, Hezi EYNALOV, Yagub GULIYEV Food and Agriculture Organization United Nations Аnkara, 2017 The designations employed and the presentation of material in this information product do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) concerning the legal or development status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The mention of specific companies or products of manufacturers, whether or not these have been patented, does not imply that these have been endorsed or recommended by FAO in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. The views expressed in this information product are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of FAO. ISBN 978-92-5-13100-5 © FAO, 2017 FAO encourages the use, reproduction and dissemination of material in this infor- mation product. Except where otherwise indicated, material may be copied, down- loaded and printed for private study, research and teaching purposes, or for use in non-commercial products or services, provided that appropriate acknowledgement of FAO as the source and copyright holder is given and that FAO’s endorsement of users’ views, products or services is not implied in any way. All requests for translation and adaptation rights, and for resale and other commercial use rights should be made via www.fao.org/contact-us/licence-request or addressed to [email protected]. -

Republic of Azerbaijan Preparatory Survey on Yashma Gas Combined Cycle Power Plant Project Final Report

Republic of Azerbaijan Azerenerji JSC Republic of Azerbaijan Preparatory Survey on Yashma Gas Combined Cycle Power Plant Project Final Report August, 2014 Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) Tokyo Electric Power Services Co., LTD Republic of Azerbaijan Preparatory Survey on Yashma Gas Combined Cycle Power Plant Project Final Report Table of Contents Table of Contents Abbreviations Units Executive Summary Page Chapter 1 Preface ............................................................................................................................ 1-1 1.1 Background of Survey .......................................................................................................... 1-1 1.2 Purpose of Survey and Scope of Survey ............................................................................... 1-1 1.2.1 Purpose of Survey .................................................................................................................. 1-1 1.2.2 Scope of Survey ..................................................................................................................... 1-1 1.2.3 Duration of the Study ............................................................................................................ 1-4 1.3 Organization of the Team ...................................................................................................... 1-6 Chapter 2 General Overview of Azerbaijan .................................................................................. 2-1 2.1 Overview of the Republic of Azerbaijan -

Azərbaycan Folkloru Və Milli-Mədəni Müxtəliflik AZƏRBAYCAN RESPUBLİKASININ PREZİDENTİ YANINDA BİLİK FONDU

Azərbaycan folkloru və milli-mədəni müxtəliflik AZƏRBAYCAN RESPUBLİKASININ PREZİDENTİ YANINDA BİLİK FONDU AZƏRBAYCAN MİLLİ ELMLƏR AKADEMİYASININ FOLKLOR İNSTİTUTU BAKI BEYNƏLXALQ MULTİKULTURALİZM MƏRKƏZİ AZƏRBAYCAN RESPUBLİKASI DİNİ QURUMLARLA İŞ ÜZRƏ DÖVLƏT KOMİTƏSİ ZAQATALA RAYON İCRA HAKİMİYYƏTİ AZƏRBAYCAN FOLKLORU VƏ MİLLİ-MƏDƏNİ MÜXTƏLİFLİK Beynəlxalq elmi-praktik konfransın MATERİALLARI Zaqatala, 19-20 may 2016-cı il Azərbaycan folkloru və milli-mədəni müxtəliflik KONFRANSIN TƏŞKİLAT ŞURASI Etibar Nəcəfov – Azərbaycan Respublikasının millətlərarası, multikulturalizm və dini məsələlər üzrə Dövlət müşaviri Xidmətinin baş məsləhətçisi, fəlsəfə üzrə elmlər doktoru, professor Mübariz Əhmədzadə – Zaqatala Rayon İcra Hakimiyyətinin başçısı Muxtar Kazımoğlu-İmanov – AMEA Folklor İnstitutunun direktoru, AMEA-nın müxbir üzvü Səyyad Salahlı – Dini Qurumlarla İş üzrə Dövlət Komitəsinin sədr müavini Oktay Səmədov – Azərbaycan Respublikasının Prezidenti yanında Bilik Fondunun icraçı direktoru, dosent İsaxan Vəliyev – Azərbaycan Respublikasının Prezidenti yanında Bilik Fondunun aparat rəhbəri, hüquq üzrə elmlər doktoru, professor TƏŞKİLAT KOMİTƏSİ Vidadi Rzayev – Azərbaycan Respublikasının Prezidenti yanında Bilik Fondunun Ölkədaxili layihələr sektorunun baş mütəxəssisi Atəş Əhmədli – AMEA Folklor İnstitutunun böyük elmi işçisi, filologiya üzrə fəlsəfə doktoru Ağaverdi Xəlil – AMEA Folklor İnstitutunun şöbə müdiri, filologiya üzrə fəlsəfə doktoru Elçin Abbasov – AMEA Folklor İnstitutunun elmi katibi, filologiya üzrə fəlsəfə doktoru Mətanət Yaqubqızı -

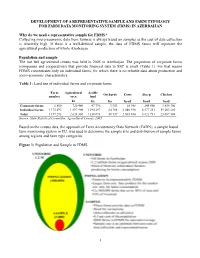

1 DEVELOPMENT of a REPRESENTATIVE SAMPLE and FARM TYPOLOGY for FARM DATA MONITORING SYSTEM (FDMS) in AZERBAIJAN Why Do We Need A

DEVELOPMENT OF A REPRESENTATIVE SAMPLE AND FARM TYPOLOGY FOR FARM DATA MONITORING SYSTEM (FDMS) IN AZERBAIJAN Why do we need a representative sample for FDMS? Collecting micro-economic data from farmers is always based on samples as the cost of data collection is relatively high. If there is a well-defined sample, the data of FDMS farms will represent the agricultural production of whole Azerbaijan. Population and sample The last full agricultural census was held in 2005 in Azerbaijan. The proportion of corporate farms (companies and cooperatives) that provide financial data to SSC is small (Table 1). For that reason FDMS concentrates only on individual farms, for which there is no reliable data about production and socio-economic characteristics. Table 1: Land use of individual farms and corporate farms Farm Agricultural Arable Orchards Cows Sheep Chicken number area land ha ha ha head head head Corporate farms 1 800 726 480 47 796 3 953 18 948 244 500 3 854 306 Individual farms 1 175 493 1 897 900 1 290 297 54 786 2 046 936 6 577 211 19 203 202 Total 1 177 293 2 624 380 1 338 093 58 739 2 065 884 6 821 711 23 057 508 Source: State Statistical Committee, Agricultural Census, 2005 Based on the census data, the approach of Farm Accountancy Data Network (FADN), a sample based farm monitoring system in EU, was used to determine the sample size and distribution of sample farms among regions and farm type categories. Figure 1: Population and Sample in FDMS 1 Most of the 1.2 million farmers in census are subsistence farmers who are not linked to the market. -

Administrative Territorial Divisions in Different Historical Periods

Administrative Department of the President of the Republic of Azerbaijan P R E S I D E N T I A L L I B R A R Y TERRITORIAL AND ADMINISTRATIVE UNITS C O N T E N T I. GENERAL INFORMATION ................................................................................................................. 3 II. BAKU ....................................................................................................................................................... 4 1. General background of Baku ............................................................................................................................ 5 2. History of the city of Baku ................................................................................................................................. 7 3. Museums ........................................................................................................................................................... 16 4. Historical Monuments ...................................................................................................................................... 20 The Maiden Tower ............................................................................................................................................ 20 The Shirvanshahs’ Palace ensemble ................................................................................................................ 22 The Sabael Castle ............................................................................................................................................. -

The State Statistical Committee of the Republic of Azerbaijan

The State Statistical Committee of the Republic of Azerbaijan RESULTS OF 2012 SAMPLE STATISTICAL SURVEY ON CONSUMPTION AND PRODUCTION OF TYPES OF ENERGY BY PRIVATE ENTERPRENEURS (NATURAL) ENTITIES BAKU – 2013 Content pag es. Introduction...................................................................................................... 65 General provisions .......................................................................................... 65 General plan of the statistical survey .............................................................. 65 Main purposes ................................................................................................. 66 Compilation of the sample design................................................................... 66 Questionnaire and methodologial guidelines on filling in.............................. 69 Data collection, analysis, input and processing .............................................. 70 Economic-statstical analysis of the results ..................................................... 70 Additions.......................................................................................................... 75 Draft of the report form 2-energy (private entrepreneur) on consumption and production of types of energy by private entrepreneurs (natural 114 persons)............................................................................................................ 64 Introduction For the purpose to execute “Plan of Actions on EC Energy Reform Support Programme for the Republic -

Agriculture in Azerbaijan and Its Development Prospects

Review article JOJ scin Volume 1 Issue 5 - August 2018 Copyright © All rights are reserved by RAE Aliyev ZH DOI: 10.19080/JOJS.2018.01.555572 Agriculture in Azerbaijan and its Development Prospects RAE Aliyev ZH* Institute for soil science and Agrochemistry of the NAS of Azerbaijan, Azerbaijan Submission: July 24, 2018; Published: August 27, 2018 *Corresponding author: RAE Aliyev ZH, Institute for soil science and Agrochemistry of the NAS of Azerbaijan, Azerbaijan, Email: Abstract This article discusses the issues of natural and economic conditions of climate, vegetation, hydrography, land cover issues of irrigated agriculture in the Republic; problems of salinity and soil erosion here. Studied agriculture in Azerbaijan state and its role in the economy of the country, where it was determined the situation of agriculture and its development, strategy and priorities of the agriculture Republic etc. Keywords: Sustainable erosion; Degradation of the environment wednesday; Resources; Arable lands Introduction processes, causing environmental degradation Wednesday, which Agriculture of the Republic of Azerbaijan is the second, after in turn covers the entire territory, which is at risk, but intensely the oil industry, the largest sector of the economy of this country. used in agricultural purposes. Further expected growth in So its sustainable, balanced development is the basis of improving agricultural production will entail strengthening the antropopresii the welfare of the people. Agricultural lands occupy 50% of the and the even greater threat of degradation of soil resources. total area of the country (including arable land-18.4%, meadows Hence the desire of the various methods (legal and economic and pastures-25.0%), agriculture employs about 18% (2005, mechanisms, education) to the balanced use and their protection 2011) the working-age population lives in rural areas and 48 per in agricultural areas.