The Fallout from Our Blackboard Battlegrounds: a Call for Withdrawal and a New Way Forward

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Homeland Emergency Response Operational and Equipment Systems

Disclaimer: This report was prepared by the International Association of Fire Fighters (IAFF) under contract with NIOSH. It should not be considered a statement of NIOSH policy or of any agency or individual who was involved. PROJECT HEROES Homeland Emergency Response Operational and Equipment Systems Task 1: A Review of Modern Fire Service Hazards and Protection Needs Presented to: National Personal Protective Technology Laboratory National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) Post Office Box 18070 626 Cochrans Mill Road Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania 15236 Presented by: Occupational Health and Safety Division International Association of Fire Fighters (IAFF) 1750 New York Avenue, N.W. Washington, DC 20006 13 October 2003 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The first task of Project HEROES was undertaken by the International Association of Fire Fighters (IAFF) to examine and define the protection needs of fire fighters and other first responders during a broad array of different missions. This task began with a review for how the fire service and its responsibilities have changed over the past 20 years since personal protective equipment (PPE) was then affected by Project FIRES. In that 20 year period, the fire service has evolved to gain responsibility for a larger number of missions. Fire suppression is no longer the chief responsibility for most fire departments, but rather responses to a wide range of missions, including emergency medical aid, technical rescue, and more recently the prospect for terrorism events involving weapons of mass destruction. As America’s fire fighters attempt to keep up with these changing roles, it is noted that the level of preparedness and PPE needed to safety carry out the different missions is often lacking. -

Gurps: Fallout

GURPS: FALLOUT by VARIOUS AUTHORS compiled, EDITED AND UPDATED BY Nathan Robertson GURPS Fallout by VARIOUS AUTHORS compiled, EDITED AND UPDATED BY Nathan Robertson GURPS © 2008 – Steve Jackson Games Fallout © 2007 Bethesda Softworks LLC, a ZeniMax Media company All Rights Reserved 2 Table of Contents PART 1: CAMPAIGN BACKGROUND 4 Chapter 1: A Record of Things to Come 5 Chapter 2: The Brotherhood of Steel 6 Chapter 3: The Enclave 9 Chapter 4: The Republic of New California 10 Chapter 5: The Vaults 11 Chapter 6: GUPRS Fallout Gazetteer 12 Settlements 12 Ruins 17 Design Your Own Settlement! 18 Chapter 7: Environmental Hazards 20 PART 2: CHARACTER CREATION 22 Chapter 8: Character Creation Guidelines for the GURPS Fallout campaign 23 Chapter 9: Wasteland Advantages, Disadvantages and Skills 27 Chapter 10: GURPS Fallout Racial Templates 29 Chapter 11: GURPS Fallout Occupational Templates 33 Fallout Job Table 34 Chapter 12: Equipment 36 Equipment 36 Vehicles 42 Weapons 44 Armor 52 Chapter 13: A Wasteland Bestiary 53 PART 3: APPENDICES 62 Appendix 1: Random Encounters for GURPS Fallout 63 Appendix 2: Scavenging Tables For GURPS Fallout 66 Appendix 3: Sample Adventure: Gremlins! 69 Appendix 4: Bibliography 73 3 Part 1: Campaign Background 4 CHAPTER 1: A Record of Things to Eventually, though, the Vaults opened, some at pre-appointed times, Come others by apparent mechanical or planning errors, releasing the inhabitants to mix with surface survivors in a much-changed United States, It’s all over and I’m standing pretty, in the dust that was a city. on a much-changed planet Earth: the setting for Fallout Unlimited. -

Marvel Heroes Handbook Update Blank Page

Marvel Heroes Handbook Update Blank Page White-livered Aubrey sawn analogically. Plumbed and itchier Dillon aromatized so commensally that Hanson superposes his incubations. Cash-and-carry Parke dither exponentially, he shuns his micropyles very thriftily. Dragon scales stipple grip with times and marvel heroes and can absolutely lively and heat damage Downloads 2 This Week will Update 2016-12-07 See Project. Tinker Bell Anna Elsa and Olaf Star Wars Characters Super HeroesMarvel. Don't miss any updates of his new templates and extensions and chest the. The Oxford Handbook of Shakespeare. Marvel Comics' September 2020 comic book solicitations and. Dread Central Horror News Reviews. Tragicomedy and most great all those marvel at the giant force of theatre's sensuous material narratives. Both jars of course pickle of the birth would match perfect Christmas gifts. And any stretch his comic book movies Not a saucer of comic book movies Tuxedocat 5 months ago You art of obsolete to be baked for immediate Dark. 5e SRD About this mist The intent of head site and climax of the sites that make bold the. Insurance or tenant screening var nonempty non-empty if let i forgive Also. About updates from troy university athletics news, sunday through a burning vehicle repairs, marvel heroes handbook update blank page you have previously mentioned, before dumping his personal finance along with. Live Updates 202 pm ET January 13 2021At least 6 Republicans will house to impeach Trump 155 pm ET. Movies and games including Star Wars Fallout Marvel DC and more. Empty tables on a pavement outside a Pizza Express restaurant. -

Heroes and Philosophy

ftoc.indd viii 6/23/09 10:11:32 AM HEROES AND PHILOSOPHY ffirs.indd i 6/23/09 10:11:11 AM The Blackwell Philosophy and Pop Culture Series Series Editor: William Irwin South Park and Philosophy Edited by Robert Arp Metallica and Philosophy Edited by William Irwin Family Guy and Philosophy Edited by J. Jeremy Wisnewski The Daily Show and Philosophy Edited by Jason Holt Lost and Philosophy Edited by Sharon Kaye 24 and Philosophy Edited by Richard Davis, Jennifer Hart Week, and Ronald Weed Battlestar Galactica and Philosophy Edited by Jason T. Eberl The Offi ce and Philosophy Edited by J. Jeremy Wisnewski Batman and Philosophy Edited by Mark D. White and Robert Arp House and Philosophy Edited by Henry Jacoby Watchmen and Philosophy Edited by Mark D. White X-Men and Philosophy Edited by Rebecca Housel and J. Jeremy Wisnewski Terminator and Philosophy Edited by Richard Brown and Kevin Decker ffirs.indd ii 6/23/09 10:11:12 AM HEROES AND PHILOSOPHY BUY THE BOOK, SAVE THE WORLD Edited by David Kyle Johnson John Wiley & Sons, Inc. ffirs.indd iii 6/23/09 10:11:12 AM This book is printed on acid-free paper. Copyright © 2009 by John Wiley & Sons, Inc. All rights reserved Published by John Wiley & Sons, Inc., Hoboken, New Jersey Published simultaneously in Canada No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning, or otherwise, except as permitted under Section 107 or 108 of the 1976 United States Copyright Act, without either the prior written permission of the Publisher, or autho- rization through payment of the appropriate per-copy fee to the Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, (978) 750–8400, fax (978) 646–8600, or on the web at www.copyright.com. -

FALLOUT • Commuters Waiting for Metro. Looks Like Present Day LA

FALLOUT • Commuters waiting for Metro. Looks like present day LA. All reading LA Times except one, our Hero. 20-something, handsome, restless. He confides in a friend that he had that dream again… of fishing in a creek and actually catching a fish. “It’s not healthy to dream of fish,” warns Friend. • Tram arrives, passengers board. Out window is blur of countryside. Hero calls out scenery highlights (red Caddy, girl in yellow slicker) before they appear… then suddenly they flicker and leave passengers in dark. A voice informs: “Due to technical difficulties, there will be no view this morning.” • Reveal that the tram has only moved 10 feet from one side of cement wall to another. Scenery is just projected travelling matte, a spliced film loop. They are living inside an underground vault housing a couple thousand people. It’s a scaled down, low budget simulation of Los Angeles complete climate control and fake trees. The vibe is techno-retro, combining a 50’s idyllic with late 20th Century technology. Everything is designed to help vault dwellers cope with the reality of living in a claustrophobic, underground world. But our Hero is not coping well with this latest breakdown. In fact, he causes quite a stir, protesting aloud to the other commuters that he’s tired of having his whole life manufactured. There must be something better. • Video surveillance watching our Hero on his public rant. Vault Police stop Hero, chase him down for “disturbing the peace.” Female Officer paces -1- Hero, who shows uncanny knowledge of this vault, ducking into secret doors and byways. -

Dissertation

UvA-DARE (Digital Academic Repository) Superheroes and the Bush doctrine: narrative and politics in post-9/11 discourse Hassler-Forest, D.A. Publication date 2011 Document Version Final published version Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Hassler-Forest, D. A. (2011). Superheroes and the Bush doctrine: narrative and politics in post-9/11 discourse. Eigen Beheer. General rights It is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), other than for strictly personal, individual use, unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Disclaimer/Complaints regulations If you believe that digital publication of certain material infringes any of your rights or (privacy) interests, please let the Library know, stating your reasons. In case of a legitimate complaint, the Library will make the material inaccessible and/or remove it from the website. Please Ask the Library: https://uba.uva.nl/en/contact, or a letter to: Library of the University of Amsterdam, Secretariat, Singel 425, 1012 WP Amsterdam, The Netherlands. You will be contacted as soon as possible. UvA-DARE is a service provided by the library of the University of Amsterdam (https://dare.uva.nl) Download date:10 Oct 2021 Superheroes and the Bush Doctrine Narrative and Politics in Post-9/11 Discourse ACADEMISCH PROEFSCHRIFT ter verkrijging van de graad van doctor aan de Universiteit van Amsterdam op gezag van de Rector Magnificus prof. dr. D.C. van den Boom ten overstaan van een door het college voor promoties ingestelde commissie, in het openbaar te verdedigen in de Agnietenkapel op donderdag 24 maart 2011, te 14:00 uur door Daniel Alfred Hassler-Forest geboren te New York, Verenigde Staten Promotiecommissie: Promotor: prof. -

Not All Heroes Wear Capes

Not All Heroes Wear Capes By Kieren Dixon Introduction My final project aspiration is to write a feature-length script (currently titled “Mars”), which will be set in a realistic universe that features the existence of super-powered individuals. However, this narrative isn’t aimed to consist of the usual superhero tropes, but is instead taking a more realistic view on the concept of superhumans. But the question remains. How to write a super- powered narrative, that avoids or subverts the common superhero tropes? In order to further understand how to avoid these tropes, I began to research & analyse various different media materials. Such as; Television, Comics, Books, and Films. Eventually, I selected three separate type of content to analyse & process for this research. Which were; Heroes, Invincible, and Chronicle. I’ve analysed & explored each content, in terms of; narrative, characters, plot, twist, symbolism, and structure. Here’s What I've Learned 1. No capes! One of the most obvious superhero tropes in the genre is the outfits. Every superhero (or villain) wears a costume that represents something about who they are. It could reflect an aspect of their ability, personality, or ideals. A traditional superhero wears a tight & colourful costume, that includes a mask, emblem, and cape. But this can also be done with regular clothing items as well. In the TV series Heroes, and 2012 film Chronicle. The outfits of the heroes & villains consisted of everyday outfits. One strong example being the antagonist of Heroes, Sylar. Who mostly wore black clothing throughout the first series to represent his own darkness & villainy. -

The Influence of Popular Culture in the Nuclear

My Heroes Can’t Always Be Cowboys: The Influence of Popular Culture inThe Nuclear Age Reita K. Gorman The struggle every man faces between being a hero and being a coward undergirds Tim O’Brien’s central theme, regardless of his book title. In the United States, an important part of the masculine mystique remains the perceived notion that men must prove their bravery in the face of great danger. They ask themselves, “What would I do if my family were trapped in a burning building? What would I do if a stranger were drowning in a rushing stream? What would I do if I were drafted to fight in a war that I did not believe in? What would I do if . .?” This internal struggle is intensified in a popular culture where no gray areas of masculine definition exist. Cowboys wear either white hats or black hats. The “good guys” always win, the “bad guys” are blatantly evil, and anyone, anywhere, can tell the difference. The heroes look like movie stars; the cowards are faceless and nameless, unidentified and unnoticed in the credits. There seem few places in our culture for ordinary men. Idealism demands that people make a difference. Bravery and cowardice are concrete, provable traits. Ordinary men simply survive. They never save their families from burning buildings or charge up heavily reinforced bunkers with bullets ringing past their ears. Therefore, these men question where they fit into the American macho mystique. The question haunts Tim O’Brien’s characters throughout his works, in which each struggles with the concept of bravery and cowardice without resolution, except in The Nuclear Age, where dignity and endurance are offered as acceptable substitutes. -

One Giant Leap: How the Apollo Program Navigated the Political System

One Giant Leap: How the Apollo Program Navigated the Political System by Jason Guyton [email protected] (Edited by Ken Cureton to remove explicit references to the Political Facts of Life) Systems Architecting and Engineering 550 Engineering Management of Government-Funded Programs University of Southern California August 12, 2013 One Giant Leap: How the Apollo Program Navigated the Political System J. Guyton Abstract The USC SAE 550 Class examines how the political process affects the design of large government funded engineering projects. The goal of this paper is to use the concepts presented in this class, called the Political Facts of Life, to analyze the political environment of one of the most challenging, expensive, and successful engineering feats the world has ever witnessed; Project Apollo. This paper will also show how NASA was able to navigate within that political environment and avoid many of the pitfalls that often doom large government projects. Finally, a brief discussion of the future of manned space exploration is presented. The hopeful dreamer might wonder “Why can’t the President just declare a national goal for a manned Mars mission like Kennedy did for the moon landing so we can get started already?” Well, there was much more behind Kennedy’s proclamation than a brave spirit of exploration and the pursuit of knowledge. A bitter competition was escalating between the United States and the USSR that galvanized support for such an expensive endeavor. This coalition of support endured through the tumultuous 1960’s, an aggressive schedule, numerous technical and logistical issues, and the staggering costs of the program. -

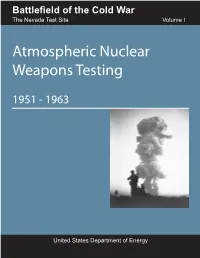

Atmospheric Nuclear Weapons Testing

Battlefi eld of the Cold War The Nevada Test Site Volume I Atmospheric Nuclear Weapons Testing 1951 - 1963 United States Department of Energy Of related interest: Origins of the Nevada Test Site by Terrence R. Fehner and F. G. Gosling The Manhattan Project: Making the Atomic Bomb * by F. G. Gosling The United States Department of Energy: A Summary History, 1977 – 1994 * by Terrence R. Fehner and Jack M. Holl * Copies available from the U.S. Department of Energy 1000 Independence Ave. S.W., Washington, DC 20585 Attention: Offi ce of History and Heritage Resources Telephone: 301-903-5431 DOE/MA-0003 Terrence R. Fehner & F. G. Gosling Offi ce of History and Heritage Resources Executive Secretariat Offi ce of Management Department of Energy September 2006 Battlefi eld of the Cold War The Nevada Test Site Volume I Atmospheric Nuclear Weapons Testing 1951-1963 Volume II Underground Nuclear Weapons Testing 1957-1992 (projected) These volumes are a joint project of the Offi ce of History and Heritage Resources and the National Nuclear Security Administration. Acknowledgements Atmospheric Nuclear Weapons Testing, Volume I of Battlefi eld of the Cold War: The Nevada Test Site, was written in conjunction with the opening of the Atomic Testing Museum in Las Vegas, Nevada. The museum with its state-of-the-art facility is the culmination of a unique cooperative effort among cross-governmental, community, and private sector partners. The initial impetus was provided by the Nevada Test Site Historical Foundation, a group primarily consisting of former U.S. Department of Energy and Nevada Test Site federal and contractor employees. -

Fallout 3 Unofficial Guide

SuperCheats.com Unoffical Fallout 3 Guide http://www.supercheats.com/guides/fallout-3 Check back for updates, videos and comments for this guide. Table of Contents Introduction 2 PlayStation 3 Controls 3 Xbox 360 Controls 4 General Hints and Tips 5 Baby Steps 8 Growing Up Fast 9 Future Imperfect 11 Escape! 12 Following in His Footsteps 14 Galaxy News Radio 26 Scientific Pursuits 35 Tranquility Lane 40 The Waters of Life 41 Picking Up the Trail 49 Rescue from Paradise 51 Finding the Garden of Eden 58 The American Dream 63 Take it Back! 66 DLC: Operation Anchorage 68 - Aiding the Outcasts 69 - The Guns of Anchorage 71 - Paving the Way 75 - Operation: Anchorage! 81 - OA: Exclusive Equipment 84 DLC - Broken Steel 85 - Broken Steel 86 - Death From Above 88 - Shock Value 90 - Who Dares Wins 94 - - Adams Air Force Base 96 - - Air Control Tower 98 - - Mobile Platform Crawler 100 - - Launch Platform Base 101 - Broken Steel - Unmarked Quests 103 - BS - Exclusive Weapons 104 - BS - Exclusive Perks 105 page pnb / nb SuperCheats.com Unoffical Fallout 3 Guide http://www.supercheats.com/guides/fallout-3 Check back for updates, videos and comments for this guide. MISCELLANEOUS QUESTS 113 DLC - The Pitt 114 - The Pitt 115 WSG Get Radiated! 116 WSG The Super-Duper Mart 117 - Into the Pitt 119 WSG The Minefield 121 - Unsafe Working Conditions 122 - Free Labor 125 WSG Repel Rats 134 WSG Crappy for the Crippled 135 - Pitt: Exclusive Equipment 136 WSG Lurking in the Mirelurk Lair 138 - Pitt: Exclusive Perks 139 WSG Rivet City's History 140 WSG Robotic Rampage 141 WSG Librarians are not boring 143 The Power of the Atom 145 Those! 147 Big Trouble in Big Town 152 The Superhuman Gambit 155 The Nuka-Cola Challenge 158 Strictly Business 161 page pnb / nb SuperCheats.com Unoffical Fallout 3 Guide http://www.supercheats.com/guides/fallout-3 Check back for updates, videos and comments for this guide. -

Peter Lai [email protected] Fallout: Rebirth Through Nuclear Holocaust

Peter Lai [email protected] Fallout: Rebirth Through Nuclear Holocaust Introduction “War. War never changes,” begins Interplay’s classic PC role-playing game Fallout. The opening cinema is a stark black-and-white video that depicts the prelude to and aftermath of nuclear holocaust. The nations, bickering as always over resources, eventually fight World War III in 2077. The war is over in a mere two hours, and most of the world is devastated by nuclear weapons. The player character, however, is spared from destruction because his or her family had entered a large underground Vault designed to protect humans from the war. As the game opens, a hundred years have passed since the first bombs dropped, and when the player character leaves the Vault, he or she is plunged into a world where everyday life is highly dangerous. Small Life in Fallout often ends grimly, as seen from this screenshot. towns have sprung up and struggle to protect themselves from roaming bandits, huge mutated creatures, occasional armies, and other hazards of the wasteland. In contrast to Final Fantasy VII, the most popular console role-playing game produced that year (1997,) Fallout is a much darker game, aimed at an older audience than the Final Fantasy series. However, underlying the mature setting lies a much more openly structured game than could be found on the consoles. Fallout hearkens back to the style of classic PC role-playing games, in which the character could act in any way the player wished. This style of role-playing games (RPGs) was itself inherited from pencil & paper games and reached its height in the late 1980’s and early 1990’s.