Williamson Umn 0130E 13794.Pdf (773.8Kb Application/Pdf)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Social and Cultural Changes That Affected the Music of Motown Records from 1959-1972

Columbus State University CSU ePress Theses and Dissertations Student Publications 2015 The Social and Cultural Changes that Affected the Music of Motown Records From 1959-1972 Lindsey Baker Follow this and additional works at: https://csuepress.columbusstate.edu/theses_dissertations Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Baker, Lindsey, "The Social and Cultural Changes that Affected the Music of Motown Records From 1959-1972" (2015). Theses and Dissertations. 195. https://csuepress.columbusstate.edu/theses_dissertations/195 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Publications at CSU ePress. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of CSU ePress. The Social and Cultural Changes that Affected the Music of Motown Records From 1959-1972 by Lindsey Baker A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of Requirements of the CSU Honors Program for Honors in the degree of Bachelor of Music in Performance Schwob School of Music Columbus State University Thesis Advisor Date Dr. Kevin Whalen Honors Committee Member ^ VM-AQ^A-- l(?Yy\JcuLuJ< Date 2,jbl\5 —x'Dr. Susan Tomkiewicz Dean of the Honors College ((3?7?fy/L-Asy/C/7^ ' Date Dr. Cindy Ticknor Motown Records produced many of the greatest musicians from the 1960s and 1970s. During this time, songs like "Dancing in the Street" and "What's Going On?" targeted social issues in America and created a voice for African-American people through their messages. Events like the Mississippi Freedom Summer and Bloody Thursday inspired the artists at Motown to create these songs. Influenced by the cultural and social circumstances of the Civil Rights Movement, the musical output of Motown Records between 1959 and 1972 evolved from a sole focus on entertainment in popular culture to a focus on motivating social change through music. -

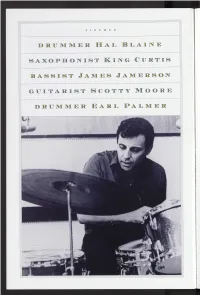

James Jamerson 2000.Pdf

able to conjure up the one lick, fill or effect that perfected albums. Live at Fillmore West exhibits Curtis the bandleader the sound. Some of his best work is found on those records. at his absolute best on a night when his extraordinary players There’s little else to say about Hal Blaine that the music included Bernard Purdie, Jerry Jemmott and Cornell Dupree. itself doesn’t communicate. But I’ll tell you one experience I His 1962 “Soul Twist” single MfclNumber One on the R&B had that showed me just how widespread his influence has charts and the Top Twenty on the pop charts, and made such been. Hal was famous for rubber-stamping his name upon an impression on Sam Cooke that he referred to it in “Having all the charts to which he contributed. In 1981, after one of a Party:” But nothing King Curtis did on his own ever scaled our concerts at Wembley Arena, Bruce asked me into his the Promethean heights of his sax work as a sideman, where dressing room. He pointed to the wall and said, “Look at he mastered the ability to be an individual within a group, that.” I looked at the wall but didn’t see anything except peel standing out but never overshadowing the artists he was sup ing wallpaper. “Look closer,” he said. Finally, I kneeled down porting and mastering the little nuances that made winners to the spot he was pointing to, and - to my great surprise - of the records on which he played. His was a rare voice j a rare in a crack in the paper, rubber-stamped on the w a ll, there it sensibility, a rare soul; and that sound - whether it be caress was: HAL BLAINE STRIKES AGAIN. -

The 50 Greatest Rhythm Guitarists 12/25/11 9:25 AM

GuitarPlayer: The 50 Greatest Rhythm Guitarists 12/25/11 9:25 AM | Sign-In | GO HOME NEWS ARTISTS LESSONS GEAR VIDEO COMMUNITY SUBSCRIBE The 50 Greatest Rhythm Guitarists Darrin Fox Tweet 1 Share Like 21 print ShareThis rss It’s pretty simple really: Whatever style of music you play— if your rhythm stinks, you stink. And deserving or not, guitarists have a reputation for having less-than-perfect time. But it’s not as if perfect meter makes you a perfect rhythm player. There’s something else. Something elusive. A swing, a feel, or a groove—you know it when you hear it, or feel it. Each player on this list has “it,” regardless of genre, and if there’s one lesson all of these players espouse it’s never take rhythm for granted. Ever. Deciding who made the list was not easy, however. In fact, at times it seemed downright impossible. What was eventually agreed upon was Hey Jazz Guy, October that the players included had to have a visceral impact on the music via 2011 their rhythm chops. Good riffs alone weren’t enough. An artist’s influence The Bluesy Beauty of Bent was also factored in, as many players on this list single-handedly Unisons changed the course of music with their guitar and a groove. As this list David Grissom’s Badass proves, rhythm guitar encompasses a multitude of musical disciplines. Bends There isn’t one “right” way to play rhythm, but there is one truism: If it feels good, it is good. The Fabulous Fretwork of Jon Herington David Grissom’s Awesome Open Strings Chuck Berry I don"t believe it A little trick for guitar chords on mandolin MERRY, MERRY Steve Howe is having a Chuck Berry changed the rhythmic landscape of popular music forever. -

Scotty Moore 2000.Pdf

Following the company to the West Coast, Jamerson spent the last ten years of his life trying to recapture the glory he had experienced in Detroit. But as much as he tried, the scene was foreign to him, and without the emotional support of Hitsville’s Funk Brothers, Jamerson faltered. Alco holism and emotional prob lems diminished his talents, eventually ending his life in 1983. At Jamerson’s funeral, Stevie Wonder eulogized how James had changed the fabric of his and all of our lives. Certainly, the leg endary bassist’s imprint has been indelibly etched onto our popular culture: Every time you’ve ever partied to a Motown record, that seis mic event making your feet move was James Jamerson’s bass. When backseat Romeos across America made their best moves to the soundtrack of Smoke/s silky thing else and was real keen to succeed.” smooth voice crooning through the dashboard speaker, In that nutshell, Phillips (who was speaking to Colin Escott Jamerson was right there. And as G.I.S shivered with fear in and Martin Hawkins for their book Good Rockin’ Tonight) some God-forsaken Southeast Asia foxhole and found a few summarized everything that was and is special about Winfield moments of solace in Marvin Gaye’s “What’s Going On,” “Scotty” Moore, one of the architects of rock & roll guitar. Even Jamerson was there too. the muted criticism regarding Atkins’s influence speaks to By the time his Motown tenure ended, Jamerson had Moore’s strengths. Like Atkins, Moore plays with precision, played on a staggering total of fifty-six Number One R&B hits hitting every note cleanly, but still manages to convey a loose- and twenty-three Number One pop hits. -

Director Francis Ford Coppola Once Remarked of His Place in Modem

NON PERFORMER “I’M NOT THE OLDEST OF ognized a truth that would soon transform the the young guys,” director record business: Underground, album-oriented Francis Ford Coppola once rock was giving birth to artists whose creativity, remarked of his place in longevity and widespread commercial appeal modem Hollywood. “I’m would at least equal that of established main the youngest of the bid stream performers and, indeed, ultimately guys.” That surprising - and surprisingly apt - become the mainstream. His belief in the assessment can be applied with even greater artistic legitimacy and commercial efficacy of illumination to the extraordinarily wide- the new music scene became an evolving ranging career and contributions of record epiphany for CBS as Davis bet the record com executive Clive Davis. pany’s future on rock. The presence of Bob Dylan and the Byrds on During his tenure as president, Davis and its roster notwithstanding, Columbia Records company created and nurtured a far-reaching was hardly a rock powerhouse in 1967when its and well-balanced rock roster. Aside from new president, Clive Davis, ventured west to Joplin, the list of performers he signed or the Monterey Pop Festival. A Brooklyn-bred, whose careers he would champion came to Harvard-educated lawyer with a taste for include Laura Nyro, Donovan, Sly and the Broadway show tunes and a reputation as a Family Stone, Blood, Sweat and Tears, hard worker and a good deal maker, Davis Santana, Loggins and Messina, Bruce hardly seemed uniquely suited to lead the Springsteen, Aerosmith, Chicago, Pink Floyd, company through a burgeoning musical and the Mahavishnu Orchestra and Billy Joel. -

Billboard 1976-02-21

February 21, 1976 Section 2 m.,.., 'ti42 CONTEMPORARY GORDON LIGHTFOOT LOGGINS & MESSINA KIP ADDOTA MAZING RHYTHM ACES MAHAVISHNU ORCHESTRA ANNA MARIA ALBERGHETTI M'3ROSIA TAJ MAHAL THE ALLEN FAMILY AMERICA MAHOGANY RUSH AB CALLOWAY LYNN ANDERSON ROGER MILLER ICK CAPRI RTFUL DODGER TIM MOORE ETULA CLARK HE ASSOCIATION MARIA MULDAUR AT COOPER BURT BACHARACH ANNE MURRAY ORM CROSBY EACH BOYS JUICE NEWTON AND ILLY DANIELS SILVERSPUR EFF BECK OHN DAVIDSON BLOOD, SWEAT & TEARS OLIVIA NEWTON -JOHN HILLIS DILLER TONY ORLANDO & DAWN PAT BOONE LIFTON DAVIS GILBERT O'SULLIVAN DAVID BOWIE BILLY ECKSTINE PARIS CAMEL BARBARA EDEN BILLY PAUL CAPTAIN & TENNILE KELLY GARRETT POINTER SISTERS ARAVAN THE GOLDDIGGERS PRELUDE ERIC CARMEN BUDDY GRECO PRETTY THINGS CARPENTERS KATHE GREEN ALAN PRICE CLIMAX BLUES BAND OEL GREY LOU RAWLS BILLY COBHAM ICK GREGORY RENAISSANCE NATALIE COLE LORENCE HENDERSON RETURN TO FOREVER LINT HOLMES GENE COTTEN Featuring COREA, B.J. COULSON CLARKE, DIMEOLA. UDSON BROTHERS CROWN HEIGHTS AFFAIR WHITE ALLY KELLERMAN MAC DAVIS LINDA RONSTADT EORGE KIRBY DE FRANCO FAMILY DAVID RUFFIN RANKIE LAINE THE 5TH DIMENSION FRED SMOOT HARI LEWIS BO DONALDSON PHOEBE SNOW AL LINDEN & THE HEYWOODS TOM SNOW HIRLEY MACLAINE KENNY ROGERS STAPLE SINGERS McMAHON AND THE FIRST EDITI STATUS QUO ONY MARTIN & FLEETWOOD MAC RAY STEVENS CYD CHARISSE FLO & EDDIE AND AL STEWART ARILYN MICHAELS THE TURTLES ILLS BROTHERS RORY GALLAGHER STEPHEN STILLS SWEET IM NABORS BOBBY GOLDSBORO JAMES TAYLOR OB NEWHART GRAND FUNK RAILROAD LILY TOMLIN NTHONY NEWLEY AL GREEN -

Standing in the Shadows of Motown (2002) You Can't Hurry Fame: Motown's Unsung Heroes

Standing in the Shadows of Motown (2002) You Can't Hurry Fame: Motown's Unsung Heroes Cast & Crew Director : Paul Justman Producer : Paul Justman , Sandford Passman , Alan Slutsky Screenwriter : Walter Dallas , Ntozake Shange Starring : Richard 'Pistol' Allen, Jack Ashford , Bob Babbitt , Benny 'Papa Zita' Benjamin, Eddie 'Bongo' Brown, Bootsy Collins , Johnny Griffith , Ben Harper , Joe Hunter , James Jamerson , Uriel Jones , Montell Jordan , Chaka Khan , Gerald Levert ,Joe Messina , Me'Shell NdegéOcello, Joan Osborne Director: Paul Justman Writers: Ntozake Shange (Narration), Alan Slutsky (book),and 1 more credit » Stars: Joe Hunter , Jack Ashford and Uriel Jones By ELVIS MITCHELL Published: November 15, 2002 ''Forty-one years after they played their first note on a Motown record and three decades since they were all together, the Funk Brothers reunited in Detroit to play their music and tell their story,'' reads a title early in the director Paul Justman's documentary ''Standing in the Shadows of Motown.'' It is a simple premise that this movie more than lives up to, falling back on the serene power of the Funk Brothers, the squadron of elite musicians heard laying down the rhythm -- and the law -- on Motown's greatest hits. This salute to the literally unsung and underrecognized studio heroes of Motown is so good because it is one of those rare documentaries that combine information with smashing entertainment. And it is one of the few nonfiction films that will have you walking out humming the score, if you're not running to the nearest store to buy Motown CD's. The movie, which opens nationwide today, shifts among four components: performers lining up to offer heartfelt but uninvolving tributes to the Funk Brothers; the musicians talking about performances that turned sheet music into legendary recordings; new renditions of Motown classics with the Funk Brothers backing up guest vocalists like Ben Harper; and dramatic re-creations of Funk Brother anecdotes. -

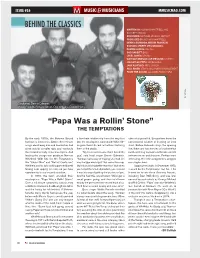

Behind the Classics

ISSUE #36 MMUSICMAG.COM BEHIND THE CLASSICS WRITTEN BY: NORMAN WHITFIELD AND BARRETT STRONG RECORDED: MOTOWN STUDIOS, DETROIT PRODUCED BY: NORMAN WHITFIELD DENNIS EDWARDS, MELVIN FRANKLIN, RICHARD STREET, OTIS WILLIAMS, DAMON HARRIS: VOCALS BOB BABBITT: BASS URIEL JONES: DRUMS WAH-WAH WATSON, JOE MESSINA: GUITARS JOHNNY GRIFFITH: KEYBOARDS JACK ASHFORD: PERCUSSION PAUL RISER: STRING AND HORN ARRANGEMENT FROM THE ALBUM: ALL DIRECTIONS (1972) Richard Street Richard Clockwise: Dennis Edwards, Melvin Franklin, Richard Street, Otis Williams, Damon Harris “Papa Was a Rollin’ Stone” THE TEMPTATIONS By the early 1970s, the Motown Sound a love-hate relationship from the very first rules of a typical hit. Songwriters know the had lost its innocence. Simple three-minute time the vocal quintet worked with Whitfield— conventional wisdom of keeping an intro songs about baby love and heartaches had he gave them hits, but not without torturing short. Before Edwards sings the opening given way to complex epic soul workouts them in the studio. line, there are two minutes of instrumental that tackled socially conscious topics. And “My first reaction was that I hated the build—and long instrumental breaks stretch leading the charge was producer Norman guy,” said lead singer Dennis Edwards. between verses and choruses. Perhaps most Whitfield. With hits for the Temptations “Norman had a way of making you mad. He interesting, the entire song motors along on like “Cloud Nine” and “Ball of Confusion,” was the type who’d yell, ‘You sound like crap. one single chord. Whitfield and his lyric-writing partner Barrett My kid could sing better than this!’ But when Topping the charts in December 1972, Strong kept upping the ante on just how you heard the finished product, you realized it would be the Temptations’ last No. -

Motown: the Sound of Young America: This Course Covers the Golden Age of Motown 1960-73

Motown: The Sound of Young America: This course covers the golden age of Motown 1960-73. It will concentrate on the people who started, nurtured, and established the label as the driving force behind American popular music in that period. The course will do this through several media: lectures, photographs, recorded music, film clips, question and answer sessions, and the use of live music. The instructor will play piano, guitar and sing, and will choose appropriate examples from each genre. Week-by-Week Course Outline and Syllabus Suggested reading and viewing for the course, suggested listening by week, plus audio playlist and video clips for each week which represent songs and performances specific to that week. Reading: To Be Loved: The Music, the Magic, the Memories of Motown : An Autobiography by Berry Gordy, 1994 Where Did Our Love Go, by Nelson George (1986) Motown: Music, Money, Sex, and Power by Gerald Posner (2005) Smokey: Inside My Life by Smokey Robinson, David Ritz (1989) Nowhere to Run, The Story of Soul Music, by Gerri Hershey (1985) The Original Marvelettes: Motown's Mystery Girl Group, by Marc Taylor, The Supremes: A Saga of Motown Dreams, Success, and Betrayal Ain't Too Proud to Beg: The Troubled Lives and Enduring Soul of the Temptations by Mark Ribowsky 2010 Mary Wells: The Tumultuous Life of Motown's First Superstar Between Each Line of Pain and Glory: My Life Story, by Gladys Knight, 1998 Standing in the Shadows of Motown, an autobiography. The Life and Music of Legendary Bassist James Jamerson (1989) with CD, transcriptions of his bass parts Viewing: Motown 25: Yesterday, Today, Forever, TV documentary 1983 The TAMI Show, 1964: the iconic, historic rock and roll TV special. -

Standing in the Shadows of Motown: the Life and Music of Legendary Bassist James Jamerson Pdf, Epub, Ebook

STANDING IN THE SHADOWS OF MOTOWN: THE LIFE AND MUSIC OF LEGENDARY BASSIST JAMES JAMERSON PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Allan Slutsky | 194 pages | 01 Jul 1996 | Hal Leonard Corporation | 9780881888829 | English | Milwaukee, United States James Jamerson | Biography & History | AllMusic Estimated between Fri. Delivery times may vary, especially during peak periods and will depend on when your payment clears - opens in a new window or tab. International postage and import charges paid to Pitney Bowes Inc. Learn More - opens in a new window or tab International postage and import charges paid to Pitney Bowes Inc. Learn More - opens in a new window or tab Any international postage and import charges are paid in part to Pitney Bowes Inc. Learn More - opens in a new window or tab Any international postage is paid in part to Pitney Bowes Inc. Learn More - opens in a new window or tab. Related sponsored items Feedback on our suggestions - Related sponsored items. Slade - Cum On Feel the Hitz. Report item - opens in a new window or tab. Description Postage and payments. Seller assumes all responsibility for this listing. Item specifics Condition: New: A new, unread, unused book in perfect condition with no missing or damaged pages. See the seller's listing for full details. See all condition definitions — opens in a new window or tab Read more about the condition. Sheet Music Station musicianshouse Music Theory Books etc. Business seller information. Complete information. Returns policy. Take a look at our Returning an item help page for more details. You're covered by the eBay Money Back Guarantee if you receive an item that is not as described in the listing. -

Gold Thunder

Gold Thunder 1 Gold Thunder 2 Gold Thunder Accolades for Tony Tony Newton has always been on the leading edge of music. His style and precision has long been recognized by real players in the industry. – Clarence McDonald Grammy Winning Keyboardist TonyNewton, one of the most talented entities I have ever had the plea- sure to hear and get to know, Truly a diamond that will not be hidden-. Jauqo III-X,Bassist/Producer I met Tony at a Motown session, I had heard through the vine as well as hearing his playing how great he was, he was Smokey Robinson's musi- cal director and played with Tony Williams, whom I admired what a great musician talent as well as a great person Tony. James Gadson – World Renowned Drummer/Producer Mean Streets Rock Magazine of Los Angeles states, “Tony Newton is a monumental master and true music visionary!” I have never met anybody in my life that has given me the truth in so dif- ferent many forms -- Life long lessons that inspire, guide, teach, follow through, and just totally give it all. Tony is not only one of the greatest musicians I've ever heard or worked with, but through him, I have been given the opportunity to see music and life through the eyes of a true genius! Tony, we love you, Mike, Marcia, and Dalton. – MMM Music Tony Newton, is one of the best creative minds I come across in my life- time and he is also a real musical genius dating back to Motown as a mu- sician known as the baby funk brother – Lou Nathan, CEO Nexxus Ent. -

Earl Palmer 2000.Pdf

unbearable intensity - so much so that historians are still try Earl’s beat is simple, dignified and reinforces the song’s sen ing to make sense of what happened during those years in the timents, “I got no time for talkin’/I got to keep a-walkin’.” Sun studio. Parading is a way of life in New Orleans, and its street But what happened and what it all means is right there on rhythm was captured on those early records. Nurtured by that the records. Listen to the tender, single-string fills on “I Love heritage, Earl’s rock & roll drumming contains all the vitality You Because,” evoking Big Bill Broonzy; the aggressive chord- and drive of a handful of street musicians who inspired the ing and deft double-string-curling-into-single-string solos second-line march. that launched “Good Rockin’ Tonight” into the ozone; the As Hal Blaine related to the 1960s West Coast style, so Earl amazing textures Moore conjured from chortlal vamping and Palmer did to the development and success of the 1950s New double- and single-string fills, rendering the heartbreak pal Orleans sound. The musicians on these New Orleans classics - pable in “You’re a Heartbreaker.” Then there’s “Mystery Earl, Salvador Doucette on piano, Lee Allen and “Red” Tyler Train ” pure and simple a work of art by all involved, and from on saxes, Frank Fields on bass, Ernest McLean and Justin a guitarist’s standpoint, still something of a rock & roll Adams on guitars and Dave Bartholomew on trumpet - were Rosetta stone.