Expanding Jack Kerouac's “America”: Canadian

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Importance of Mobilty in Jack Kerouac's on the Road And

SOBİAD Mart 2015 Onur KAYA IMPORTANCE OF MOBILTY IN JACK KEROUAC’S ON THE ROAD AND DENNIS HOPPER’S EASY RIDER Arş. Gör. Onur KAYA Abstract Journey as a mobility in 1950s and 1960s of the United States of America showed itself in the works of authors and directors of the films. Among them, Jack Kerouack’s On The Road (1955) and Dennis Hopper’s Easy Rider (1969) are significant works. Analysing both works will put forth representation of mobility in America and the period. For the method, mobility notion will be emphasized. The mobility notion in works and representation of its effects on people, period will be analyzed. Comparison of representation of mobility in two works will be done. Finally, the study will reveal the importance of mobility in the American society. Key Words: Beats, 50s, 60s, Mobility, Road JACK KEROUAC’IN ON THE ROAD VE DENNIS HOPPER’IN EASY RIDER YAPITLARINDA HAREKETLİLİĞİN ÖNEMİ Öz Yolculuk bir hareketlilik olarak Amerika Birleşik Devletlerinin 1950ler ve 1960larında yazarlarla film yönetmenlerinin eserlerinde kendisini göstermiştir. Bunlar içerisinde Jack Kerouack’ın On The Road (1955) ve Dennis Hopper’ın Easy Rider (1969) eserleri önemli yapıtlardır. Her iki eserin incelenmesi o dönemde ve Amerika’da hareketliliğin temsilini ortaya koyacaktır. Metot olarak hareketlilik kavramı irdelenecektir. Eserlerdeki hareketlilik kavramı ve onun insanlarla dönem üzerindeki etkileri analiz edilecektir. Her iki eserdeki hareketlililiğin temsilinin karşılaştırılması yapılacaktır. Sonuç olarak çalışma Amerikan toplumundaki hareketliliğin -

Canada's Public Space

CBC/Radio-Canada: Canada’s Public Space Where we’re going At CBC/Radio-Canada, we have been transforming the way we engage with Canadians. In June 2014, we launched Strategy 2020: A Space for Us All, a plan to make the public broadcaster more local, more digital, and financially sustainable. We’ve come a long way since then, and Canadians are seeing the difference. Many are engaging with us, and with each other, in ways they could not have imagined a few years ago. Our connection with the people we serve can be more personal, more relevant, more vibrant. Our commitment to Canadians is that by 2020, CBC/Radio-Canada will be Canada’s public space where these conversations live. Digital is here Last October 19, Canadians showed us that their future is already digital. On that election night, almost 9 million Canadians followed the election results on our CBC.ca and Radio-Canada.ca digital sites. More precisely, they engaged with us and with each other, posting comments, tweeting our content, holding digital conversations. CBC/Radio-Canada already reaches more than 50% of all online millennials in Canada every month. We must move fast enough to stay relevant to them, while making sure we don’t leave behind those Canadians who depend on our traditional services. It’s a challenge every public broadcaster in the world is facing, and CBC/Radio-Canada is further ahead than many. Our Goal The goal of our strategy is to double our digital reach so that 18 million Canadians, one out of two, will be using our digital services each month by 2020. -

Cbc Radio One, Today

Stratégies gagnantes Auditoires et positionnement Effective strategies Audiences and positioning Barrera, Lilian; MacKinnon, Emily; Sauvé, Martin 6509619; 5944927; 6374185 [email protected]; [email protected]; [email protected] Rapport remis au professeur Pierre C. Bélanger dans le cadre du cours CMN 4515 – Médias et radiodiffusion publique 14 juin 2014 TABLE OF CONTENT ABSTRACT ......................................................................................... 2 INTRODUCTION .................................................................................. 3 CBC RADIO ONE, TODAY ...................................................................... 4 Podcasting the CBC Radio One Channel ............................................... 6 The Mobile App for CBC Radio One ...................................................... 7 Engaging with Audiences, Attracting New Listeners ............................... 9 CBC RADIO ONE, TOMORROW ............................................................. 11 Tomorrow’s Audience: Millennials ...................................................... 11 Fishing for Generation Y ................................................................... 14 Strengthening Market-Share among the Middle-aged ............................ 16 Favouring CBC Radio One in Institutional Settings ................................ 19 CONCLUSION .................................................................................... 21 REFERENCES .................................................................................... -

“Howl”—Allen Ginsberg (1959) Added to the National Registry: 2006 Essay by David Wills (Guest Post)*

“Howl”—Allen Ginsberg (1959) Added to the National Registry: 2006 Essay by David Wills (guest post)* Allen Ginsberg, c. 1959 The Poem That Changed America It is hard nowadays to imagine a poem having the sort of impact that Allen Ginsberg’s “Howl” had after its publication in 1956. It was a seismic event on the landscape of Western culture, shaping the counterculture and influencing artists for generations to come. Even now, more than 60 years later, its opening line is perhaps the most recognizable in American literature: “I saw the best minds of my generation destroyed by madness…” Certainly, in the 20h century, only T.S. Eliot’s “The Waste Land” can rival Ginsberg’s masterpiece in terms of literary significance, and even then, it is less frequently imitated. If imitation is the highest form of flattery, then Allen Ginsberg must be the most revered writer since Hemingway. He was certainly the most recognizable poet on the planet until his death in 1997. His bushy black beard and shining bald head were frequently seen at protests, on posters, in newspapers, and on television, as he told anyone who would listen his views on poetry and politics. Alongside Jack Kerouac’s 1957 novel, “On the Road,” “Howl” helped launch the Beat Generation into the public consciousness. It was the first major post-WWII cultural movement in the United States and it later spawned the hippies of the 1960s, and influenced everyone from Bob Dylan to John Lennon. Later, Ginsberg and his Beat friends remained an influence on the punk and grunge movements, along with most other musical genres. -

Jack Kerouac and the Influence Of

JACK KEROUAC AND THE INFLUENCE OF BEBOP by David Kastin* _________________________________________________________ [This is an excerpt from David Kastin’s book Nica’s Dream: The Life and Legend of the Jazz Baroness, pages 58-62.] ike many members of his generation, Jack Kerouac had been enthralled by the dynamic rhythms of the swing era big bands he listened to on the radio as a L teenager. Of course, what he heard was the result of the same racial segregation that was imposed on most areas of American life. The national radio networks, as well as most of the independent local stations, were vigilant in protecting the homes of the dominant culture against the intrusion of any and all soundwaves of African American origin. That left a lineup of all-white big bands, ranging from "sweet" orchestras playing lush arrangements of popular songs to "hot" bands who provided a propulsive soundtrack for even the most fervent jitterbugs. Jack Kerouac: guided to the riches of African American culture… ________________________________________________________ *David Kastin is a music historian and educator who in 2011 was living in Brooklyn, New York. He was the author of the book I Hear America Singing: An Introduction to Popular Music, and a contributor to DownBeat, the Village Voice and the Da Capo Best Writing series. 1 After graduating from Lowell High School in 1939, Kerouac left the red-brick Massachusetts mill town for New York City, where he had been awarded a football scholarship to Columbia University. In order to bolster his academic credentials and put on a few pounds before his freshman season, Jack was encouraged to spend a year at Horace Mann, a Columbia-affiliated prep school popular with New York's middle-class intellectual elite. -

Song and Nationalism in Quebec

Song and Nationalism in Quebec [originally published in Contemporary French Civilization, Volume XXIV, No. 1, Spring /Summer 2000] The québécois national mythology is dependent on oral culture for sustenance. This orality, while allowing a popular transmission of central concepts, also leaves the foundations of a national francophone culture exposed to influence by the anglophone forces that dominate world popular culture. A primary example is song, which has been linked to a nationalist impulse in Quebec for over thirty years. What remains of that linkage today? Economic, cultural, political and linguistic pressures have made the role of song as an ethnic and national unifier increasingly ambiguous, and reflect uncertainties about the Quebec national project itself, as the Quebec economy becomes reflective of global trends toward supranational control. A discussion of nationalism must be based on a shared understanding of the term. Anthony Smith distinguishes between territorial and ethnic definitions: territorially defined nations can point to a specific territory and rule by law; ethnies, on the other hand, add a collective name, a myth of descent, a shared history, a distinctive culture and a sense of solidarity to the territorial foundation. If any element among these is missing, it must be invented. This “invention” should not be seen as a negative or devious attempt to distort the present or the past; it is part of the necessary constitution of a “story” which can become the foundation for a national myth-structure. As Smith notes: "What matters[...] is not the authenticity of the historical record, much less any attempt at 'objective' methods of historicizing, but the poetic, didactic and integrative purposes which that record is felt to disclose" (25). -

Cahiers-Papers 53-1

The Giller Prize (1994–2004) and Scotiabank Giller Prize (2005–2014): A Bibliography Andrew David Irvine* For the price of a meal in this town you can buy all the books. Eat at home and buy the books. Jack Rabinovitch1 Founded in 1994 by Jack Rabinovitch, the Giller Prize was established to honour Rabinovitch’s late wife, the journalist Doris Giller, who had died from cancer a year earlier.2 Since its inception, the prize has served to recognize excellence in Canadian English-language fiction, including both novels and short stories. Initially the award was endowed to provide an annual cash prize of $25,000.3 In 2005, the Giller Prize partnered with Scotiabank to create the Scotiabank Giller Prize. Under the new arrangement, the annual purse doubled in size to $50,000, with $40,000 going to the winner and $2,500 going to each of four additional finalists.4 Beginning in 2008, $50,000 was given to the winner and $5,000 * Andrew Irvine holds the position of Professor and Head of Economics, Philosophy and Political Science at the University of British Columbia, Okanagan. Errata may be sent to the author at [email protected]. 1 Quoted in Deborah Dundas, “Giller Prize shortlist ‘so good,’ it expands to six,” 6 October 2014, accessed 17 September 2015, www.thestar.com/entertainment/ books/2014/10/06/giller_prize_2014_shortlist_announced.html. 2 “The Giller Prize Story: An Oral History: Part One,” 8 October 2013, accessed 11 November 2014, www.quillandquire.com/awards/2013/10/08/the-giller- prize-story-an-oral-history-part-one; cf. -

„As Always the Lunch Is Naked‟ Jack Kerouac‟S

Universiteit Gent Academiejaar 2006-2007 „AS ALWAYS THE LUNCH IS NAKED‟ FORMAL EXPERIMENTS OF THE BEAT GENERATION FOCUSSING ON JACK KEROUAC‟S SPONTANEOUS PROSE AND WILLIAM BURROUGHS‟S CUT-UPS Promotor: Gert Buelens Verhandeling voorgelegd aan de faculteit Letteren en Wijsbegeerte voor het verkrijgen van de graad licenciaat in de taal- en letterkunde: Germaanse Talen door Lien De Coster 2 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I‟d like to thank Gert Buelens, my promoter, Ishrat Lindblad, Olga Putilina, and Rickey Mantley for their revisions, useful comments, enthusiasm and interest. 3 DEDICATION Last year, when I lived in Sweden, I caught a lung inflammation after I went swimming in the ice. One day during my long recovery, a friend of mine brought me a book. It was The Dharma Bums by Jack Kerouac. When I finally got better we talked about it, and for the first time I heard about the Beats. Back then my friend had a hard time defining who they were and my understanding did not come that evening – it came gradually through frequenting Wirströms, the wonderful jazz bar where the musicians made „IT‟ happen every week during the Tuesday jam session, through a lot of walking and talking in the everchanging everlasting woods, through travelling by myself, with my backpack as my only companion. Gradually it came - till the day the friend who had given me the book sent me a letter. When I read it, I knew I understood; 4 Monday, March 6, 2006, 4:53 AM last night i meet a old man(60 i think) spanish man in that party where i invite you... -

The Impact of World War Ii on Personal and Social Life As Portrayed in Jack Kerouac’S on the Road and Kim Won-Il’S the Wind and the River: a Comparative Literature

THE IMPACT OF WORLD WAR II ON PERSONAL AND SOCIAL LIFE AS PORTRAYED IN JACK KEROUAC’S ON THE ROAD AND KIM WON-IL’S THE WIND AND THE RIVER: A COMPARATIVE LITERATURE A THESIS BY MIRA APRIANTI REG. NO. 130705093 DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH FACULTY OF CULTURAL STUDIES UNIVERSITY OF SUMATERA UTARA MEDAN 2017 Universitas Sumatera Utara Universitas Sumatera Utara Universitas Sumatera Utara Universitas Sumatera Utara AUTHOR’S DECLARATION I, MIRA APRIANTI DECLARE THAT I AM THE SOLE AUTHOR OF THIS THESIS EXCEPT WHERE REFERENCE IS MADE IN THE TEXT OF THIS THESIS. THIS THESIS CONTAINS NO MATERIAL PUBLISHED ELSEWHERE OR EXTRACTED IN WHOLE OR IN PART FROM A THESIS BY WHICH I HAVE QUALIFIED FOR OR AWARDED ANOTHER DEGREE. NO OTHER PERSON’S WORK HAS BEEN USED WITHOUT DUE ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS IN THE MAIN TEXT OF THIS THESIS. THIS THESIS HAS NOT BEEN SUBMITTED FOR THE AWARD OF ANOTHER DEGREE IN ANY TERTIARY EDUCATION. Signed : Date : August 22nd, 2017 v Universitas Sumatera Utara COPYRIGHT DECLARATION NAME : MIRA APRIANTI TITLE OF THESIS : THE IMPACT OF WORLD WAR II ON PERSONAL AND SOCIAL LIFE AS PORTRAYED IN JACK KEROUAC’S ON THE ROAD AND KIM WON-IL’S THE WIND AND THE RIVER: A COMPARATIVE LITERATURE QUALIFICATION : S-1/ SARJANA SASTRA DEPARTMENT : ENGLISH I AM WILLING THAT MY THESIS SHOULD BE AVAILABLE FOR REPRODUCTION AT THE DISCRETION OF THE LIBRARIAN OF DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH, FACULTY OF CULTURAL STUDIES, UNIVERSITY OF SUMATERA UTARA ON THE UNDERSTANDING THAT USERS ARE MADE AWARE OF THEIR OBLIGATION UNDER THE LAW OF THE REPUBLIC OF INDONESIA. Signed : Date : August 22nd, 2017 vi Universitas Sumatera Utara ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Bismillahirrahmanirrahim. -

December 2013 VOL XXI, Issue 12, Number 248

December 2013 VOL XXI, Issue 12, Number 248 Editor: Klaus J. Gerken European Editor: Mois Benarroch Contributing Editors: Michael Collings; Jack R. Wesdorp; Heather Ferguson; Patrick White Previous Associate Editors: Igal Koshevoy; Evan Light; Pedro Sena; ; Oswald Le Winter ISSN 1480-6401 Selected Works by Ron Whitehead with Photographs by Jinn INTRODUCTION The Emperor Has No Clothes (Poem by Jinn) PHOTO 1 by jinn PHOTO 2 by jinn Section 1 Tapping My Own Phone I WILL NOT BOW DOWN The Dance Kentucky Blues Mama Sex Education Music Saved My Life and Bob Dylan Saved My Soul listen dog, sky Jasper Joyce San Francisco, May 1993 Oh Nameless Section 2 PHOTO by Jinn Secrets Thousands of Shrieking Devils Ritual Night the black talent dark conceit the grinding of her bones ghost lover my final farewell Trance Mission Section 3 PHOTO by Jinn How Many More Times No More Fingers Pointing to The Moon You Grow Wild in My Heart samurai sword go down all night listening treasure our flowered home Section 4 PHOTO by Jinn Moxley and Eirene Moonshine King Burgoo Queen the loneliest picture i've ever seen without blinking plowed earth the shape of water purple orchid dawn endless river sail on Section 5 PHOTO by Jinn westward into the canyoned night a ruin i new mexico Naked Interview: Conversations with William S. Burroughs CALLING THE TOADS Can Art Matter? For as Long as Space Endures Section 6 PHOTO by Jinn The Storm Generation Manifesto i refuse POST SCRIPTUM Section 7 PHOTO by Jinn NEVER GIVE UP (in English/Icelandic/Spanish) back cover (end of Journal) -

Approche Du Poétique Dans La Chanson Francophone Québécoise

UNIVERSITÉ DU QUÉBEC À MONTRÉAL APPROCHE DU POÉTIQUE DANS LA CHANSON FRANCOPHONE QUÉBÉCOTSE MÉMOIRE PRÉSENTÉ COMME EXIGENCE PARTIELLE DE LA MAÎTRISE EN ÉTUDES LITTÉRAfRES PAR VÉRONIQUE BTSSON FÉVRIER 2011 UNIVERSITÉ DU QUÉBEC À MONTRÉAL Service des bibliothèques Avertissement La diffusion de ce mémoire se fait dans le respect des droits de son auteur, qui a signé le formulaire Autorisation de reproduire et de diffuser un travail de recherche de cycles supérieurs (SDU-522 - Rév.01-2006). Cette autorisation stipule que «conformément à l'article 11 du Règlement no 8 des études de cycles supérieurs, [l'auteur] concède à l'Université du Québec à Montréal une licence non exclusive d'utilisation et de publication de la totalité ou d'une partie importante de [son] travail de recherche pour des fins pédagogiques et non commerciales. Plus précisément, [l'auteur] autorise l'Université du Québec à Montréal à reproduire, diffuser, prêter, distribuer ou vendre des copies de [son] travail de recherche à des fins non commerciales sur quelque support que ce soit, y compris l'Internet. Cette licence et cette autorisation n'entraînent pas une renonciation de [la] part [de l'auteur] à [ses] droits moraux ni à [ses] droits de propriété intellectuelle. Sauf entente contraire, [l'auteur] conserve la liberté de diffuser et de commercialiser ou non ce travail dont [il] possède un exemplaire.» REMERCIEMENTS Je désire remercier monsieur Dominique Garand de l'Université du Québec à Montréal d'avoir accepté de diriger la rédaction de mon mémoire. Je le remercie pour sa patience, sa passion réelle de la chanson et de tous les aspects qui l'entourent. -

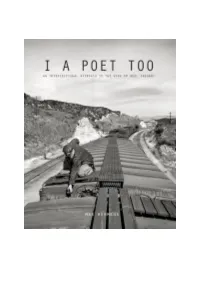

An Intersectional Approach to the Work of Neal Cassady

“I a poet too”: An Intersectional Approach to the Work of Neal Cassady “Look, my boy, see how I write on several confused levels at once, so do I think, so do I live, so what, so let me act out my part at the same time I’m straightening it out.” Max Hermens (4046242) Radboud University Nijmegen 17-11-2016 Supervisor: Dr Mathilde Roza Second Reader: Prof Dr Frank Mehring Table of Contents Acknowledgements 3 Abstract 4 Introduction 5 Chapter I: Thinking Along the Same Lines: Intersectional Theory and the Cassady Figure 10 Marginalization in Beat Writing: An Emblematic Example 10 “My feminism will be intersectional or it will be bullshit”: Towards a Theoretical Framework 13 Intersectionality, Identity, and the “Other” 16 The Critical Reception of the Cassady Figure 21 “No Profane History”: Envisioning Dean Moriarty 23 Critiques of On the Road and the Dean Moriarty Figure 27 Chapter II: Words Are Not For Me: Class, Language, Writing, and the Body 30 How Matter Comes to Matter: Pragmatic Struggles Determine Poetics 30 “Neal Lived, Jack Wrote”: Language and its Discontents 32 Developing the Oral Prose Style 36 Authorship and Class Fluctuations 38 Chapter III: Bodily Poetics: Class, Gender, Capitalism, and the Body 42 A poetics of Speed, Mobility, and Self-Control 42 Consumer Capitalism and Exclusion 45 Gender and Confinement 48 Commodification and Social Exclusion 52 Chapter IV: Writing Home: The Vocabulary of Home, Family, and (Homo)sexuality 55 Conceptions of Home 55 Intimacy and the Lack 57 “By their fruits ye shall know them” 59 1 Conclusion 64 Assemblage versus Intersectionality, Assemblage and Intersectionality 66 Suggestions for Future Research 67 Final Remarks 68 Bibliography 70 2 Acknowledgements First off, I would like to thank Mathilde Roza for her assistance with writing this thesis.