1 Theorizing Liminal Cinema

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Journal of Bengali Studies

ISSN 2277-9426 Journal of Bengali Studies Vol. 6 No. 1 The Age of Bhadralok: Bengal's Long Twentieth Century Dolpurnima 16 Phalgun 1424 1 March 2018 1 | Journal of Bengali Studies (ISSN 2277-9426) Vol. 6 No. 1 Journal of Bengali Studies (ISSN 2277-9426), Vol. 6 No. 1 Published on the Occasion of Dolpurnima, 16 Phalgun 1424 The Theme of this issue is The Age of Bhadralok: Bengal's Long Twentieth Century 2 | Journal of Bengali Studies (ISSN 2277-9426) Vol. 6 No. 1 ISSN 2277-9426 Journal of Bengali Studies Volume 6 Number 1 Dolpurnima 16 Phalgun 1424 1 March 2018 Spring Issue The Age of Bhadralok: Bengal's Long Twentieth Century Editorial Board: Tamal Dasgupta (Editor-in-Chief) Amit Shankar Saha (Editor) Mousumi Biswas Dasgupta (Editor) Sayantan Thakur (Editor) 3 | Journal of Bengali Studies (ISSN 2277-9426) Vol. 6 No. 1 Copyrights © Individual Contributors, while the Journal of Bengali Studies holds the publishing right for re-publishing the contents of the journal in future in any format, as per our terms and conditions and submission guidelines. Editorial©Tamal Dasgupta. Cover design©Tamal Dasgupta. Further, Journal of Bengali Studies is an open access, free for all e-journal and we promise to go by an Open Access Policy for readers, students, researchers and organizations as long as it remains for non-commercial purpose. However, any act of reproduction or redistribution (in any format) of this journal, or any part thereof, for commercial purpose and/or paid subscription must accompany prior written permission from the Editor, Journal of Bengali Studies. -

Profile Profile

MARWAR INDIA I MARCH-APRIL 2018 20 PROFILE 21 WITCHING OVER FROM THE BUSINESS OF MAKING rakhis (an ornamental thread that serves as an amulet which sisters ritualistically tie around the wrists of their brothers on Raksha Bandhan) to something as glamorous as producing films may seem hard to conceive, but for Shrikant Mohta and Mahendra Soni it happened as if by divine intervention. Not only did the cousins’ foray into filmdom happen against all odds, but success greeted them from the get-go. The growth has continued SHOOTING unabated for over two decades since and today their company, SVF Entertainment, is the largest film production and distribution TO FAME house in Eastern India. College kids to film distributors The Mohtas originally belong to Bikaner in Rajasthan, but have been living in Kolkata for the last three generations, where they own one of the country’s biggest rakhi manufacturing companies. Rather than pick up the baton, as is the usual practice among Marwaris, Shrikant Mohta and cousin Mahendra Soni decided to turn their efforts in another direction, which led to the foundation of Shree Venkatesh Films (now renamed SVF Entertainment), which has grown phenomenally over the years, earning the sobriquet ‘Yashraj Films of the East’. So how did it all begin? “We started way back in 1995,” says Shrikant Mohta, who is 43 now and the creative muscle of SVF Entertainment. “We were two young energetic boys still in college pursuing a bachelor’s degree in commerce when we thought we can become dream merchants, but with no idea on how to sell dreams, as till then we were only involved in our family For Shrikant Mohta and Mahendra Soni, there is no business like Many of SVF's films went on show business. -

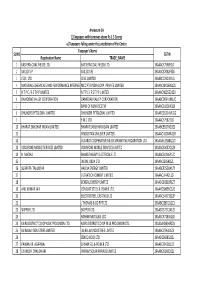

Uttar Dinajpur District Court List of Eligible Candidates Staff Recruitment 2018

UTTAR DINAJPUR DISTRICT COURT LIST OF ELIGIBLE CANDIDATES STAFF RECRUITMENT 2018 APPLICATION SRL NO POST APPLICANT'S NAME FATHER'S/MOTHER'S/SPOUSE'S NAME NO 1 ENGLISH STENOGRAPHER 10000016 SUJIT SARKAR LATE SATISH CHANDRA SARKAR 2 ENGLISH STENOGRAPHER 10000022 RIA MITRA LATE ANJAN MITRA 3 ENGLISH STENOGRAPHER 10000036 RAMKRISHNA PAL KANAN CHANDRA PAL 4 ENGLISH STENOGRAPHER 10000049 CHIRANTAN CHAKRABORTY LT. GIRIDHARI CHAKRABORTY 5 ENGLISH STENOGRAPHER 10000057 BINAY KISPOTTA LT- RENGHU KISPOTTA 6 ENGLISH STENOGRAPHER 10000075 RAKTIMA SAHA GAUTAM SAHA 7 ENGLISH STENOGRAPHER 10000097 SANU LAMA MAN BAHADUR LAMA 8 ENGLISH STENOGRAPHER 10000161 RAJDEEP DAS CHHABI DAS 9 ENGLISH STENOGRAPHER 10000182 SHUBHAM KARMAKAR BISNU PADA KARMAKAR 10 ENGLISH STENOGRAPHER 10000274 ARKA BISWAS LATE TAPAN CHANDRA BISWAS 11 ENGLISH STENOGRAPHER 10000362 GOBINDA SANTRA ANANDA MOHAN SANTRA 12 ENGLISH STENOGRAPHER 10000467 DOLA SHARMA DEBAPRASAD SHARMA 13 ENGLISH STENOGRAPHER 10000471 AMAR MONDAL AMBIKA CH MONDAL 14 ENGLISH STENOGRAPHER 10000483 ROBINA KHATOON MD MANSOOR 15 ENGLISH STENOGRAPHER 10000516 MANASA SASMAL KASHINATH SASMAL 16 ENGLISH STENOGRAPHER 10000540 TANMAY GHOSH TAPAN KUMAR GHOSH 17 ENGLISH STENOGRAPHER 10000605 SHYAMAL MONDAL NALINI CHANDRA MONDAL 18 ENGLISH STENOGRAPHER 10000691 KOUSHIK THOKDAR SHIB SHANKAR THOKDAR 19 ENGLISH STENOGRAPHER 10000752 BHAIRAB SINGHA LATE AJOY KUMAR SINGHA 20 ENGLISH STENOGRAPHER 10000791 SIMA MONDAL LATE SUSANTA MONDAL 21 ENGLISH STENOGRAPHER 10000909 JAWAID AHMED WAJIHUDDIN AHMED 22 ENGLISH STENOGRAPHER 10000933 -

A Study on Promotional Strategies of Selected Bengali Movies in 2014

IJMSS Vol.03 Issue-12 (December, 2015) ISSN: 2321-1784 International Journal in Management and Social Science (Impact Factor- 4.358) A STUDY ON PROMOTIONAL STRATEGIES OF SELECTED BENGALI MOVIES IN 2014 Dr. Dev Malya Dutta, Professor of Marketing, Department of Business Administration, The University of Burdwan, Burdwan, West Bengal, India Jyotirmoy Mazumder, Head of BBA(H), Tarakeswar Degree College, Tarakeswar, Hooghly, West Bengal, India ABSTRACT Like other film industries, Bengali film industry or Tollywood started applying marketing tools keeping in view on various genre films that have been produced in recent times with shorter release window. Distribution has been transformed through digitization along with increase of multiplexes. Bengali cinema raised its budget & marketing expenditure to boost the business, increasing the gross income to some limited number of films but lags far behind the success of even South Indian films. Hence, film promotion techniques are used with the growth in audience research area, where Word of Mouth & Viral Marketing play an important role across most demographic and socio-economic levels, to enhance the size of the market and to help the business in its expansion across larger regions in order to earn higher gross income per film, as the number of film releases are more in recent years. Keyword: social media, marketing strategy, film production & promotion, revenue, film industry, single screen, multiplex, audience research, digitization. Introduction 2014 has shown a sharp decrease in revenue in all film markets viz. Indian Regional, Bollywood & Hollywood. Number of successful films has been far less than the previous two years globally. Only the second half of the year garnered some good revenue through few hits, where the last quarter of the year was the brightest one (according to different media reports of the period). -

Bachchan 2014 Bengali Movie Release Date

Bachchan 2014 bengali movie release date click here to download Release date. 26 September (). Running time. Country, India. Language, Bengali. Bachchan is an Bengali comedy thriller directed by Raja Chanda and produced under the Plot · Production · Casting · Soundtrack. Action · Bachchan is an upcoming Bengali Action-Comedy-Thriller film directed by Raja Photos. Bachchan () Add Image Director: Baba Yadav. Bachchan () cast and crew credits, including actors, actresses, directors, writers and more. Film Editing by Second Unit Director or Assistant Director. Bachchan is an Bengali Action-Comedy-Thriller film. The film feature actors Jeet and Aindrita Ray in. of "Bachchan - Bengali Movie", an upcoming bengali film starring Jeet, (Official) - Jeet, Aindrita. Watch All Bangla Natok,Movies Only on Truebanglatv subscribe for more. Bachchan is an Bengali. The film stars Jeet, Aindrita Ray, Payel Sarkar, Mukul Dev, Ashish Vidyarthi, Kharaj Mu BACHCHAN. Bachchan (Bengali) (), thriller released in Bengali language in theatre near you in Kolkata. Know about Film reviews, lead cast & crew. Check out actor, actress, director and other cast and crew members of Bachchan bengali movie online on www.doorway.ru The two September 26 releases — Bachchan and Chotushkone — have made producer Reliance Entertainment proud. Today's Edition, | Thursday, November 13, | When can you say a Bengali film is a hit? When a film's first-run. Even when making an out and out entertainer, the director could have spent some time on the New Bengali Movie Bachchan Review By. Movie: Buddha Mil Gaya Music Director: R D Burman Singers: Kishore Kumar Director: Hrishikesh Mukherjee Lyrics: Majrooh Sultanpuri Enjoy this super hit. -

Films 2018.Xlsx

List of feature films certified in 2018 Certified Type Of Film Certificate No. Title Language Certificate No. Certificate Date Duration/Le (Video/Digita Producer Name Production House Type ngth l/Celluloid) ARABIC ARABIC WITH 1 LITTLE GANDHI VFL/1/68/2018-MUM 13 June 2018 91.38 Video HOUSE OF FILM - U ENGLISH SUBTITLE Assamese SVF 1 AMAZON ADVENTURE Assamese DIL/2/5/2018-KOL 02 January 2018 140 Digital Ravi Sharma ENTERTAINMENT UA PVT. LTD. TRILOKINATH India Stories Media XHOIXOBOTE 2 Assamese DIL/2/20/2018-MUM 18 January 2018 93.04 Digital CHANDRABHAN & Entertainment Pvt UA DHEMALITE. MALHOTRA Ltd AM TELEVISION 3 LILAR PORA LEILALOI Assamese DIL/2/1/2018-GUW 30 January 2018 97.09 Digital Sanjive Narain UA PVT LTD. A.R. 4 NIJANOR GAAN Assamese DIL/1/1/2018-GUW 12 March 2018 155.1 Digital Haider Alam Azad U INTERNATIONAL Ravindra Singh ANHAD STUDIO 5 RAKTABEEZ Assamese DIL/2/3/2018-GUW 08 May 2018 127.23 Digital UA Rajawat PVT.LTD. ASSAMESE WITH Gopendra Mohan SHIVAM 6 KAANEEN DIL/1/3/2018-GUW 09 May 2018 135 Digital U ENGLISH SUBTITLES Das CREATION Ankita Das 7 TANDAB OF PANDAB Assamese DIL/1/4/2018-GUW 15 May 2018 150.41 Digital Arian Entertainment U Choudhury 8 KRODH Assamese DIL/3/1/2018-GUW 25 May 2018 100.36 Digital Manoj Baishya - A Ajay Vishnu Children's Film 9 HAPPY MOTHER'S DAY Assamese DIL/1/5/2018-GUW 08 June 2018 108.08 Digital U Chavan Society, India Ajay Vishnu Children's Film 10 GILLI GILLI ATTA Assamese DIL/1/6/2018-GUW 08 June 2018 85.17 Digital U Chavan Society, India SEEMA- THE UNTOLD ASSAMESE WITH AM TELEVISION 11 DIL/1/17/2018-GUW 25 June 2018 94.1 Digital Sanjive Narain U STORY ENGLISH SUBTITLES PVT LTD. -

Festival Catalogue 2015

Jio MAMI 17th MUMBAI FILM FESTIVAL with 29 OCTOBER–5 NOVEMBER 2015 1 2 3 4 5 12 October 2015 MESSAGE I am pleased to know that the 17th Jio MAMI Mumbai Film Festival is being organised by the Mumbai Academy of Moving Image (MAMI) in Mumbai from 29th October to 5th November 2015. Mumbai is the undisputed capital of Indian cinema. This festival celebrates Mumbai’s long and fruitful relationship with cinema. For the past sixteen years, the festival has continued promoting cultural and MRXIPPIGXYEP I\GLERKI FIX[IIR ½PQ MRHYWXV]QIHME TVSJIWWMSREPW ERH GMRIQE IRXLYWMEWXW%W E QYGL awaited annual culktural event, this festival directs international focus to Mumbai and its continued success highlights the prominence of the city as a global cultural capital. I am also happy to note that the 5th Mumbai Film Mart will also be held as part of the 17th Mumbai Film Festival, ensuring wider distribution for our cinema. I congratulate the Mumbai Academy of Moving Image for its continued good work and renewed vision and wish the 17th Jio MAMI Mumbai Film Festival and Mumbai Film Mart grand success. (CH Vidyasagar Rao) 6 MESSAGE Mumbai, with its legacy, vibrancy and cultural milieu, is globally recognised as a Financial, Commercial and Cultural hub. Driven by spirited Mumbaikars with an indomitable spirit and great affection for the city, it has always promoted inclusion and progress whilst maintaining its social fabric. ,SQIXSXLI,MRHMERH1EVEXLM½PQMRHYWXV]1YQFEMMWXLIYRHMWTYXIH*MPQ'ETMXEPSJXLIGSYRXV] +MZIRXLEX&SPP][SSHMWXLIQSWXTVSPM½GMRHYWXV]MRXLI[SVPHMXMWSRP]FI½XXMRKXLEXE*MPQ*IWXMZEP that celebrates world cinema in its various genres is hosted in Mumbai. -

FINAL DISTRIBUTION.Xlsx

Annexure-1A 1)Taxpayers with turnover above Rs 1.5 Crores a) Taxpayers falling under the jurisdiction of the Centre Taxpayer's Name SL NO GSTIN Registration Name TRADE_NAME 1 EASTERN COAL FIELDS LTD. EASTERN COAL FIELDS LTD. 19AAACE7590E1ZI 2 SAIL (D.S.P) SAIL (D.S.P) 19AAACS7062F6Z6 3 CESC LTD. CESC LIMITED 19AABCC2903N1ZL 4 MATERIALS CHEMICALS AND PERFORMANCE INTERMEDIARIESMCC PTA PRIVATE INDIA CORP.LIMITED PRIVATE LIMITED 19AAACM9169K1ZU 5 N T P C / F S T P P LIMITED N T P C / F S T P P LIMITED 19AAACN0255D1ZV 6 DAMODAR VALLEY CORPORATION DAMODAR VALLEY CORPORATION 19AABCD0541M1ZO 7 BANK OF NOVA SCOTIA 19AAACB1536H1ZX 8 DHUNSERI PETGLOBAL LIMITED DHUNSERI PETGLOBAL LIMITED 19AAFCD5214M1ZG 9 E M C LTD 19AAACE7582J1Z7 10 BHARAT SANCHAR NIGAM LIMITED BHARAT SANCHAR NIGAM LIMITED 19AABCB5576G3ZG 11 HINDUSTAN UNILEVER LIMITED 19AAACH1004N1ZR 12 GUJARAT COOPERATIVE MILKS MARKETING FEDARATION LTD 19AAAAG5588Q1ZT 13 VODAFONE MOBILE SERVICES LIMITED VODAFONE MOBILE SERVICES LIMITED 19AAACS4457Q1ZN 14 N MADHU BHARAT HEAVY ELECTRICALS LTD 19AAACB4146P1ZC 15 JINDAL INDIA LTD 19AAACJ2054J1ZL 16 SUBRATA TALUKDAR HALDIA ENERGY LIMITED 19AABCR2530A1ZY 17 ULTRATECH CEMENT LIMITED 19AAACL6442L1Z7 18 BENGAL ENERGY LIMITED 19AADCB1581F1ZT 19 ANIL KUMAR JAIN CONCAST STEEL & POWER LTD.. 19AAHCS8656C1Z0 20 ELECTROSTEEL CASTINGS LTD 19AAACE4975B1ZP 21 J THOMAS & CO PVT LTD 19AABCJ2851Q1Z1 22 SKIPPER LTD. SKIPPER LTD. 19AADCS7272A1ZE 23 RASHMI METALIKS LTD 19AACCR7183E1Z6 24 KAIRA DISTRICT CO-OP MILK PRO.UNION LTD. KAIRA DISTRICT CO-OP MILK PRO.UNION LTD. 19AAAAK8694F2Z6 25 JAI BALAJI INDUSTRIES LIMITED JAI BALAJI INDUSTRIES LIMITED 19AAACJ7961J1Z3 26 SENCO GOLD LTD. 19AADCS6985J1ZL 27 PAWAN KR. AGARWAL SHYAM SEL & POWER LTD. 19AAECS9421J1ZZ 28 GYANESH CHAUDHARY VIKRAM SOLAR PRIVATE LIMITED 19AABCI5168D1ZL 29 KARUNA MANAGEMENT SERVICES LIMITED 19AABCK1666L1Z7 30 SHIVANANDAN TOSHNIWAL AMBUJA CEMENTS LIMITED 19AAACG0569P1Z4 31 SHALIMAR HATCHERIES LIMITED SHALIMAR HATCHERIES LTD 19AADCS6537J1ZX 32 FIDDLE IRON & STEEL PVT. -

FINAL DISTRIBUTION.Xlsx

Annexure-1B 1)Taxpayers with turnover above Rs 1.5 Crores b) Taxpayers falling under the jurisdiction of the State Taxpayer's Name SL NO GSTIN Registration Name TRADE_NAME 1 NATIONAL INSURANCE COMPANY LIMITED NATIONAL INSURANCE COMPANY LTD 19AAACN9967E1Z0 2 WEST BENGAL STATE ELECTRICITY DISTRIBUTION CO. LTD WEST BENGAL STATE ELECTRICITY DISTRIBUTION CO. LTD 19AAACW6953H1ZX 3 INDIAN OIL CORPORATION LTD.(ASSAM OIL DIVN.) INDIAN OIL CORPORATION LTD.(ASSAM OIL DIVN.) 19AAACI1681G1ZM 4 THE W.B.P.D.C.L. THE W.B.P.D.C.L. 19AABCT3027C1ZQ 5 ITC LIMITED ITC LIMITED 19AAACI5950L1Z7 6 TATA STEEL LIMITED TATA STEEL LIMITED 19AAACT2803M1Z8 7 LARSEN & TOUBRO LIMITED LARSEN & TOUBRO LIMITED 19AAACL0140P1ZG 8 SAMSUNG INDIA ELECTRONICS PVT. LTD. 19AAACS5123K1ZA 9 EMAMI AGROTECH LIMITED EMAMI AGROTECH LIMITED 19AABCN7953M1ZS 10 KOLKATA PORT TRUST 19AAAJK0361L1Z3 11 TATA MOTORS LTD 19AAACT2727Q1ZT 12 ASHUTOSH BOSE BENGAL CRACKER COMPLEX LIMITED 19AAGCB2001F1Z9 13 HINDUSTAN PETROLEUM CORPORATION LIMITED. 19AAACH1118B1Z9 14 SIMPLEX INFRASTRUCTURES LIMITED. SIMPLEX INFRASTRUCTURES LIMITED. 19AAECS0765R1ZM 15 J.J. HOUSE PVT. LTD J.J. HOUSE PVT. LTD 19AABCJ5928J2Z6 16 PARIMAL KUMAR RAY ITD CEMENTATION INDIA LIMITED 19AAACT1426A1ZW 17 NATIONAL STEEL AND AGRO INDUSTRIES LTD 19AAACN1500B1Z9 18 BHARATIYA RESERVE BANK NOTE MUDRAN LTD. BHARATIYA RESERVE BANK NOTE MUDRAN LTD. 19AAACB8111E1Z2 19 BHANDARI AUTOMOBILES PVT LTD 19AABCB5407E1Z0 20 MCNALLY BHARAT ENGGINEERING COMPANY LIMITED MCNALLY BHARAT ENGGINEERING COMPANY LIMITED 19AABCM9443R1ZM 21 BHARAT PETROLEUM CORPORATION LIMITED 19AAACB2902M1ZQ 22 ALLAHABAD BANK ALLAHABAD BANK KOLKATA MAIN BRANCH 19AACCA8464F1ZJ 23 ADITYA BIRLA NUVO LTD. 19AAACI1747H1ZL 24 LAFARGE INDIA PVT. LTD. 19AAACL4159L1Z5 25 EXIDE INDUSTRIES LIMITED EXIDE INDUSTRIES LIMITED 19AAACE6641E1ZS 26 SHREE RENUKA SUGAR LTD. 19AADCS1728B1ZN 27 ADANI WILMAR LIMITED ADANI WILMAR LIMITED 19AABCA8056G1ZM 28 AJAY KUMAR GARG OM COMMODITY TRADING CO. -

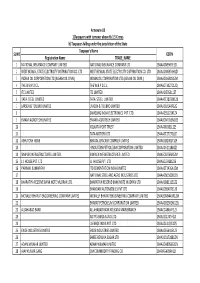

Tapasi Das 20150003 Ba(English Honours)

Name Code Number Course Name RUKAIYA FARZANA RESHMI 20150001 B.A.(ENGLISH HONOURS) TAPASI DAS 20150003 B.A.(ENGLISH HONOURS) DELOWAR HUSSAN 20150005 B.A.(ENGLISH HONOURS) AVISHEK SARKAR 20150006 B.A.(ENGLISH HONOURS) BAPPA PAUL 20150009 B.A.(ENGLISH HONOURS) SUSMITA SARKAR 20150011 B.A.(ENGLISH HONOURS) ABU BAKKAR SIDDIK 20150012 B.A.(ENGLISH HONOURS) BARSHA DAS 20150013 B.A.(ENGLISH HONOURS) SANDIP MAJUMDAR 20150014 B.A.(ENGLISH HONOURS) PANCHAMI ROY 20150015 B.A.(ENGLISH HONOURS) AKLEMA KHATUN 20150016 B.A.(ENGLISH HONOURS) SUDIPTA SARKAR 20150017 B.A.(ENGLISH HONOURS) DEEPA MALLICK 20150018 B.A.(ENGLISH HONOURS) ABDUR RAKIB 20150019 B.A.(ENGLISH HONOURS) JAHANGIR ALAM 20150020 B.A.(ENGLISH HONOURS) NIRUPAM BARMAN 20150021 B.A.(ENGLISH HONOURS) BHAGYASRI SARKAR 20150023 B.A.(ENGLISH HONOURS) HANGSHA PATI SIKDAR 20150024 B.A.(ENGLISH HONOURS) TIYAS BHATTACHARYA 20150025 B.A.(ENGLISH HONOURS) KOYEL GUHA 20150027 B.A.(ENGLISH HONOURS) RIMA DAS 20150028 B.A.(ENGLISH HONOURS) TANIMA GUHA 20150029 B.A.(ENGLISH HONOURS) SOURAV BISWAS 20150031 B.A.(ENGLISH HONOURS) BIPASHA PARVIN 20150033 B.A.(ENGLISH HONOURS) HADISA KHATUN 20150034 B.A.(ENGLISH HONOURS) SAMPA ROY 20150035 B.A.(ENGLISH HONOURS) INDRANI SARKAR 20150036 B.A.(ENGLISH HONOURS) ISHITA TALUKDAR 20150037 B.A.(ENGLISH HONOURS) BARNALI MONDAL 20150038 B.A.(ENGLISH HONOURS) RAMA ROY 20150039 B.A.(ENGLISH HONOURS) SUBRATA ROY 20150040 B.A.(ENGLISH HONOURS) MURSHID ALAM 20150041 B.A.(ENGLISH HONOURS) DIPANKAR CHANDRA ROY 20150042 B.A.(ENGLISH HONOURS) ISRAIL ALAM 20150043 B.A.(ENGLISH -

ODU MOVIES SRL PORTFOLIO.Pages

! PORTFOLIO | FEATURE MOVIES 1. March 2017 Movie Katamarayudu, North Star Entertainment & Pawan Kalyan (Hyderabad, India) Shot in Trentino (Castel Thun, Castel Beseno, Monte Bondone, Riva del Garda) Crew Size: 75; Days of shoot: 6 2. December 2016 Short Film Far East (Italy) Shot in Lucca Coproduction: ODU Movies and Ass. Effetto Cinema Crew Size: 40; Days of shoot: 7 3. November 2016 Movie Haripada Bandwala, Shree Venkatesh Films (Kolkata, India) Shot in Aosta Valley, Como & Milan Crew Size: 30; Days of shoot: 4 4. August 2016 Movie Abhimaan, Grassroot Entertainent & Reliance Industries (Kolkata, India) Shot in Rome, Vada (White Beaches), Genova, Zermatt & Locarno (Swiss) and Milan Crew Size: 45; Days of shoot: 9 5. August 2016 Movie FU - Friendship Unlimited, Cut 2 Cut Movie & Mahesh Manjrekar (Mumbai, India) Shot in Milan, Lecco, Como, Varenna, Pavia, Locarno (Swiss) Crew Size: 45; Days of shoot: 7 6. August 2016 Movie Rubik’s Cube, Ahaley’s Movie Magic & Mahesh Manjrekar (Mumbai, India) Shot in Cervinia and Aosta Crew Size: 45; Days of shoot: 5 7. November 2015 Movie Despicable You, Shanghai Maimeng Film and Television Media (Shanghai, China) Shot in Verona Crew Size: 75; Days of shoot: 3 8. November 2015 Movie One Way Ticket, KNC Media & Entertainment (Mumbai, India) Shot on the Costa Cruise, between Savona, Rome, Barcelona, Marseille and Genova. Crew Size: 40; Days of shoot: 15 ! !1 / !10 ! 9. July 2015 Movie Thala 56, Shri Saai Raam Creations – A M Rathnam (Chennai, India) Shot in Milan, Aosta Valley, Viareggio (Tuscany) and Cuneo (Piedmont) Crew Size: 65; Days of shoot: 10 10. -

Le Halua Le Full Bengali Movie Download

Le Halua Le Full Bengali Movie Download Le Halua Le Full Bengali Movie Download 1 / 3 2 / 3 13 Jun 2012 . Le Halua Le (2012) DVD Rip Bengali Movie Download. Posted by Bibhuti . Click Here To View Screen Shoot Full Size. Note: Download.. 5 Jul 2012 . Le Halua Le (2012) Bengali full Movie HD dow. Download This Software through Downloader (Fast Instalation). Le Halua Le Today i want to.. Where to Watch Le Halua Le Full Movie Streaming. Le Halua Le is a 2012 Bengali-language Indian feature comedy film directed by Raja Chanda, starring.. 30 Mar 2012 - 2 min - Uploaded by SVFProducer : Shree Venkatesh Films & Surinder Films Presenter : Shrikant Mohta & Nispal Singh .. Bengali Movies I Have Seen Ever . Rajatabha Dutta in Le Halua Le (2012) Mithun Chakraborty and Payel . See full summary . Trending Indian Movies.. 1 Feb 2016 - 4 minWatch Darling O Amar Darling - Le Halua Le - full 720p HD by KIds Zone on .. Laptop Bangla Full Movie Free HD Download In MP4 Bangla Film, Laptop Bangla Download Free Movie . Le Halua Le -Bengali Movie DVDRip [Pherarim].. Results 1 - 25 of 3909 . Studds helmet brand new ready for sale. 1400. Kasba (Kolkata). Studds ninja helmet full mask ISO CERTIFIED ready for sale. 21-Nov-.. 9 Dec 2017 - 1 min - Uploaded by Bolly ViewsLE HALUA LE 2012 Bengali Movie LifeTime WorldWide Box Office Collections Verdict .. Roommates Sonali and Subho don't get along well, but keep calm to adjust in the low-rent. Will they settle their scores? Watch the full movie on Hoichoi.. 13 Apr 2012 . Le Halua Le (Bengali) (2012), drama romance released in Bengali language in theatre near you in Kolkata.