Mpofu Abongile 2016.Pdf (2.114Mb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Health Professions Act: List of Approved Facilities for the Purposes of Performing Community Service by Dentists in the Year

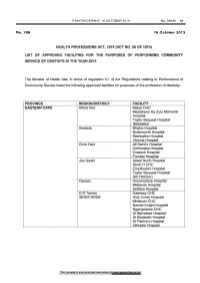

STAATSKOERANT, 16 OKTOBER 2013 No. 36936 13 No. 788 16 October 2013 HEALTH PROFESSIONS ACT, 1974 (ACT NO. 56 OF 1974) LIST OF APPROVED FACILITIES FOR THE PURPOSES OF PERFORMING COMMUNITY SERVICE BY DENTISTS IN THE YEAR 2014 The Minister of Health has, in terms of regulation 5.1 of the Regulations relating to Performance of Community Service listed the following approved facilities for purposes of the profession of dentistry. PROVINCE REGION/DISTRICT FACILITY EASTERN CAPE Alfred Nzo Maluti CHC Madzikane Ka Zulu Memorial Hospital Taylor Bequest Hospital (Matatiele) Amato le Bhisho Hospital Butterworth Hospital Madwaleni Hospital Victoria Hospital Chris Hani All Saint's Hospital Cofimvaba Hospital Cradock Hospital Frontier Hospital Joe Gqabi Aliwal North Hospital Block H CHC Empilisweni Hospital Taylor Bequest Hospital (Mt Fletcher) Cacadu Humansdorp Hospital Midlands Hospital Settlers Hospital O.R Tambo Gateway CHC ISRDS NODE Holy Cross Hospital Mhlakulo CHC Nessie Knight Hospital Ngangelizwe CHC St Barnabas Hospital St Elizabeth Hospital St Patrick's Hospital Zithulele Hospital This gazette is also available free online at www.gpwonline.co.za 14 No. 36936 GOVERNMENT GAZETTE, 16 OCTOBER 2013 FREE STATE Motheo District(DC17) National Dental Clinic Botshabelo District Hospital Fezile Dabi District(DC20) Kroonstad Dental Clinic MafubefTokollo Hospital Complex Metsimaholo/Parys Hospital Complex Lejweleputswa DistrictWelkom Clinic Area(DC18) Thabo Mofutsanyana District Elizabeth Ross District Hospital* (DC19) Itemoheng Hospital* ISRDS NODE Mantsopa -

Community Struggle from Kennedy Road Jacob Bryant SIT Study Abroad

SIT Graduate Institute/SIT Study Abroad SIT Digital Collections Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection SIT Study Abroad Fall 2005 Towards Delivery and Dignity: Community Struggle From Kennedy Road Jacob Bryant SIT Study Abroad Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcollections.sit.edu/isp_collection Part of the Politics and Social Change Commons, and the Race and Ethnicity Commons Recommended Citation Bryant, Jacob, "Towards Delivery and Dignity: Community Struggle From Kennedy Road" (2005). Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection. 404. https://digitalcollections.sit.edu/isp_collection/404 This Unpublished Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the SIT Study Abroad at SIT Digital Collections. It has been accepted for inclusion in Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection by an authorized administrator of SIT Digital Collections. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TOWARDS DELIVERY AND DIGNITY: COMMUNITY STRUGGLE FROM KENNEDY ROAD Jacob Bryant Richard Pithouse, Center for Civil Society School for International Training South Africa: Reconciliation and Development Fall 2005 “The struggle versus apartheid has been a little bit achieved, though not yet, not in the right way. That’s why we’re still in the struggle, to make sure things are done right. We’re still on the road, we’re still grieving for something to be achieved, we’re still struggling for more.” -- Sbusiso Vincent Mzimela “The ANC said ‘a better life for all,’ but I don’t know, it’s not a better life for all, especially if you live in the shacks. We waited for the promises from 1994, up to 2004, that’s 10 years of waiting for the promises from the government. -

History Workshop

UNIVERSITY OF THE WITWATERSRAND, JOHANNESBURG HISTORY WORKSHOP STRUCTURE AND EXPERIENCE IN THE MAKING OFAPARTHEID 6-10 February 1990 AUTHOR: Iain Edwards and Tim Nuttall TITLE: Seizing the moment : the January 1949 riots, proletarian populism and the structures of African urban life in Durban during the late 1940's 1 INTRODUCTION In January 1949 Durban experienced a weekend of public violence in which 142 people died and at least 1 087 were injured. Mobs of Africans rampaged through areas within the city attacking Indians and looting and destroying Indian-owned property. During the conflict 87 Africans, SO Indians, one white and four 'unidentified' people died. One factory, 58 stores and 247 dwellings were destroyed; two factories, 652 stores and 1 285 dwellings were damaged.1 What caused the violence? Why did it take an apparently racial form? What was the role of the state? There were those who made political mileage from the riots. Others grappled with the tragedy. The government commission of enquiry appointed to examine the causes of the violence concluded that there had been 'race riots'. A contradictory argument was made. The riots arose from primordial antagonism between Africans and Indians. Yet the state could not bear responsibility as the outbreak of the riots was 'unforeseen.' It was believed that a neutral state had intervened to restore control and keep the combatants apart.2 The apartheid state drew ideological ammunition from the riots. The 1950 Group Areas Act, in particular, was justified as necessary to prevent future endemic conflict between 'races'. For municipal officials the riots justified the future destruction of African shantytowns and the rezoning of Indian residential and trading property for use by whites. -

National Water

STAATSKOERANT, 7 DESEMBER 2018 No. 42092 69 DEPARTMENT OF WATER AND SANITATION NO. 1366 07 DECEMBER 2018 1366 National Water Act, 1998: Mzimvubu-Tsitsikamma Water Management Area (WMA7) in the Eastern Cape Province: Amending and Limiting the use of Water in terms of Item 6 of Schedule 3 of the Act, for Urban, Agricultural and Industrial (including Mining) purposes 42092 MZIMVUSU- TSIT$IKAMMA WATER MANAGEMENT AREA (WMA 7)IN THE EASTERN CAPE PROVINCE: AMENDING AND LIMITING THE USE OF WATER IN TERMSOF ITEM 6 OF SCHEDULE 3 OF THE NATIONAL WATER ACT OF 1998;FOR URBAN, AGRICULTURAL AND INDUSTRIAL (INCLUDING MINING) PURPOSES The Minister of Water and Sanitation has, in terms of item 6(1) of Schedule 3of the National Water Act of 1998 (Act 36 of 1998) (The Act), empowered to limit theuse of water in the area concerned if the Minister, on reasonable grounds, believes that a watershortage exists within the area concerned. This power has been delegated to me in terms of Section63 (1) (b) of the Act. Therefore,I,Deborah Mochotlhi, in my capacity as the Acting Director -Generalof the Department of Water and Sanitation hereby under delegated authority, interms of item 6 (1) of Schedule 3 read with section 72(1) of the Act, publish a notice in the gazetteto amend and limit the taking and storing of water in terms of section 21(a) and 21(b) byall users in the geographical areas listed and described below, as follows: 1. The Algoa Water Supply System (WSS) and associated primary catchments: Decrease the curtailment from 30% to 25% on all taking of waterfrom surface or groundwater resources for domestic and industrial water use from the Algoa WSS and the relevant parts of the catchments within which the Algoa WSSoccurs. -

Location in Africa the Durban Metropolitan Area

i Location in Africa The Durban Metropolitan area Mayor’s message Durban Tourism am delighted to welcome you to Durban, a vibrant city where the Tel: +27 31 322 4164 • Fax: +27 31 304 6196 blend of local cultures – African, Asian and European – is reected in Email: [email protected] www.durbanexperience.co.za I a montage of architectural styles, and a melting pot of traditions and colourful cuisine. Durban is conveniently situated and highly accessible Compiled on behalf of Durban Tourism by: to the world. Artworks Communications, Durban. Durban and South Africa are fast on their way to becoming leading Photography: John Ivins, Anton Kieck, Peter Bendheim, Roy Reed, global destinations in competition with the older, more established markets. Durban is a lifestyle Samora Chapman, Chris Chapman, Strategic Projects Unit, Phezulu Safari Park. destination that meets the requirements of modern consumers, be they international or local tourists, business travellers, conference attendees or holidaymakers. Durban is not only famous for its great While considerable effort has been made to ensure that the information in this weather and warm beaches, it is also a destination of choice for outdoor and adventure lovers, eco- publication was correct at the time of going to print, Durban Tourism will not accept any liability arising from the reliance by any person on the information tourists, nature lovers, and people who want a glimpse into the unique cultural mix of the city. contained herein. You are advised to verify all information with the service I welcome you and hope that you will have a wonderful stay in our city. -

DURBAN NORTH 957 Hillcrest Kwadabeka Earlsfield Kenville ^ 921 Everton S!Cteelcastle !C PINETOWN Kwadabeka S Kwadabeka B Riverhorse a !

!C !C^ !.ñ!C !C $ ^!C ^ ^ !C !C !C!C !C !C !C ^ ^ !C !C ^ !C !C !C !C !C ^ !C ñ !C !C !C !C !C ^ !C !C ^ !C !C $ !C ^ !C !C !C !C !C !C ^ !C ^ ñ !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !. !C ^ ñ ^ !C !C !C !C !C !C $ !C !C ^ !C ^ !C !C !C ñ !C !C !C ^ !C !.ñ ñ!C !C !C !C ^ !C ^ !C ^ !C ^ !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C ^ ñ !C !C !C !C !C !C ^ ñ !C !C ñ !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C ñ !C !C ^ ^ !C !C !. !C !C ñ ^ !C ^ !C ñ!C !C ^ ^ !C !C $ ^!C $ ^ !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !. !C !C !C ñ!.^ $ !C !C !C ^ !C !C !C !C $ !C ^ !C !C $ !C !C ñ $ !. !C !C !C !C !C !C !. ^ ñ!C ^ ^ !C $!. ^ !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !. !C !C !C !C !C ^ !C !. !C !C ñ!C !C !C !C ^ ñ !C !C ñ !C !C !. ^ !C !C !C !C !C !C !C ^ !C ñ ^ $ ^ !C ñ !C !C !. ñ ^ !C !. !C !C ^ ñ !. ^ ñ!C !C $^ ^ ^ !C ^ ñ ^ !C ^ !C !C !C !C !C !C ^ !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !. !C ^ !C $ !C !. ñ !C !C ^ !C ñ!. ^ !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C $!C !. !C ^ !. !. !C !C !. ^ !C !C !C ^ ^ !C !C ñ !C !. -

Best Practices Database: Cato Manor Development Project, Durban Page 1 of 6

Best Practices Database: Cato Manor Development Project, Durban Page 1 of 6 Subscriber: Vervoorn, IHS Subscription Expires: 01-AUG-04 Cato Manor Development Project, Durban South Africa Categories: Urban and Regional Planning: - community-based planning -urban renewal Poverty Eradication: - income generation -vocational training Social Services: - public safety Level of Activity: Neighbourhood Ecosystem: Tropical/Sub-Tropical Summary The purpose of the Cato Manor Development Project (CMDP) has been to reverse a legacy of apartheid-era planning 'worst practice', and subsequent unplanned settlement, poverty, internecine community conflict, and poor urban environmental quality. Cato Manor is strategically located near to the centre of South Africa's second largest metropolitan area, and it will soon house over 100 000 poorer people under neighbourhood conditions which external adjudicators now regard as exemplary in international context. Yet, prior to the intervention of the Cato Manor Development Association (CMDA), the area was nationally infamous for a history of forced racial removals (150 000 displaced) and, more recently, for land and home invasions, internecine political conflict and violence amongst poor communities, and an absence of urban services. In a context of a vacuum of planning authority and legitimacy in the area during the late 1980s and early 1990s, an NGO the Cato Manor Development Association (CMDA) was formed, and it initiated efforts to: Socially stabilize the area, introduce participatory planning and services upgrading, -

Following Is a Load Shedding Schedule That People Are Advised to Keep

Following is a load shedding schedule that people are advised to keep. STAND-BY LOAD SHEDDING SCHEDULE Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Saturday Sunday Block A 04:00-06:30 08:00-10:30 04:00-06:30 08:00-10:30 04:00-06:30 08:00-10:30 08:00-10:30 Block B 06:00-08:30 14:00-16:30 06:00-08:30 14:00-16:30 06:00-08:30 14:00-16:30 14:00-16:30 Block C 08:00-10:30 16:00-18:30 08:00-10:30 16:00-18:30 08:00-10:30 16:00-18:30 16:00-18:30 Block D 10:00-12:30 12:00-14:30 10:00-12:30 12:00-14:30 10:00-12:30 12:00-14:30 12:00-14:30 Block E 12:00-14:30 10:00-12:30 12:00-14:30 10:00-12:30 12:00-14:30 10:00-12:30 10:00-12:30 Block F 14:00-16:30 18:00-20:30 14:00-16:30 18:00-20:30 14:00-16:30 18:00-20:30 18:00-20:30 Block G 16:00-18:30 20:00-22:30 16:00-18:30 20:00-22:30 16:00-18:30 20:00-22:30 20:00-22:30 Block H 18:00-20:30 04:00-06:30 18:00-20:30 04:00-06:30 18:00-20:30 04:00-06:30 04:00-06:30 Block J 20:00-22:30 06:00-08:30 20:00-22:30 06:00-08:30 20:00-22:30 06:00-08:30 06:00-08:30 Area Block Albert Park Block D Amanzimtoti Central Block B Amanzimtoti North Block B Amanzimtoti South Block B Asherville Block H Ashley Block J Assagai Block F Athlone Block G Atholl Heights Block J Avoca Block G Avoca Hills Block C Bakerville Gardens Block G Bayview Block B Bellair Block A Bellgate Block F Belvedere Block F Berea Block F Berea West Block F Berkshire Downs Block E Besters Camp Block F Beverly Hills Block C Blair Atholl Block J Blue Lagoon Block D Bluff Block E Bonela Block E Booth Road Industrial Block E Bothas Hill Block F Briardene Block G Briardene -

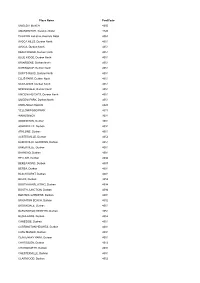

Place Name Postcode UMDLOTI BEACH 4350 AMANZIMTOTI

Place Name PostCode UMDLOTI BEACH 4350 AMANZIMTOTI, Kwazulu Natal 4126 PHOENIX Industria, Kwazulu Natal 4068 AVOCA HILLS, Durban North 4051 AVOCA, Durban North 4051 BEACHWOOD, Durban North 4051 BLUE RIDGE, Durban North 4051 BRIARDENE, Durban North 4051 DORINGKOP, Durban North 4051 DUFF'S ROAD, Durban North 4051 ELLIS PARK, Durban North 4051 NEWLANDS, Durban North 4051 SPRINGVALE, Durban North 4051 UMGENI HEIGHTS, Durban North 4051 UMGENI PARK, Durban North 4051 UMHLANGA ROCKS 4320 YELLOWWOOD PARK 4011 WANDSBECK 3631 ADDINGTON, Durban 4001 ASHERVILLE, Durban 4091 ATHLONE, Durban 4051 AUSTERVILLE, Durban 4052 BAKERVILLE GARDENS, Durban 4051 BAKERVILLE, Durban 4051 BAYHEAD, Durban 4001 BELLAIR, Durban 4094 BEREA ROAD, Durban 4007 BEREA, Durban 4001 BLACKHURST, Durban 4001 BLUFF, Durban 4052 BOOTH AANSLUITING, Durban 4094 BOOTH JUNCTION, Durban 4094 BOTANIC GARDENS, Durban 4001 BRIGHTON BEACH, Durban 4052 BROOKDALE, Durban 4051 BURLINGTON HEIGHTS, Durban 4051 BUSHLANDS, Durban 4052 CANESIDE, Durban 4051 CARRINGTON HEIGHTS, Durban 4001 CATO MANOR, Durban 4091 CENTENARY PARK, Durban 4051 CHATSGLEN, Durban 4012 CHATSWORTH, Durban 4092 CHESTERVILLE, Durban 4001 CLAIRWOOD, Durban 4052 CLARE Est/Lgd, Durban 4091 CLAYFIELD, Durban 4051 CONGELLA, Durban 4001 DALBRIDGE, Durban 4001 DORMERTON, Durban 4091 DURBAN NORTH, Durban 4051 DURBAN-NOORD, Durban 4051 Durban International Airport, Durban 4029 EARLSFIELD, Durban 4051 EAST END, Durban 4018 EASTBURY, Durban 4051 EFFINGHAM HEIGHTS, Durban 4051 FALLODEN PARK, Durban 4094 FLORIDA ROAD, Durban 4019 FOREST -

Abstract Umlazi Is Part of the Townships That Form the New City Demarcation of Ethekwini Municipality (“Ethekwini ”) As They

The scourge of post-apartheid housing in Umlazi. Mthembu N. (2007) Abstract Umlazi is part of the townships that form the new city demarcation of eThekwini Municipality (“eThekwini ”) as they were redrawn after 2000 local government elections and implemented in terms of the Municipal Structures Act, when Durban Municipality started to unify different six local councils that were previously divided under apartheid state into as administrative entities. A transformation of the administrative component of eThekwini Unicity was initiated in 2002, with a specific focus on improving service delivery, and driving economic growth and employment within the region (Joffe, 2006). eThekwini is surrounded by the iLembe to the north, the Indian ocean to the east, Ugu to south and UMgungundlovu to the west. Its population is estimated at over 2.5 million. Umlazi township is the outcome of the 1845 British occupation of what was renamed Natal after land was stolen from the indigenous populace - Zulus. It is situated 17km south west of central Durban. The Umlazi Reserve was established in 1862 by the Church of England to provide for a progressive rural life for “natives” in pursuit of pastoral and agricultural occupation. It was proclaimed a township in 1962 to house residents of Cato Manor who were moved under the slums law. Today, Umlazi (situated 17km southwest of Durban) has a population of about 400 000. Some estimates indicate a higher population figure – up to 1 million people. There are shack settlements surrounding Umlazi as well as backyard shacks in the township (Mahomed, 2002). When the ANC came to power in 1994, 'homes for all' was a key election promise. -

The Sustainable Location of Low-Income Housing Development in South African Urban Areas

Sustainable Development and Planning II, Vol. 2 1165 The sustainable location of low-income housing development in South African urban areas S. Biermann CSIR Building and Construction Technology Abstract Underpinning much of the international and local urban development and form literature, and becoming increasingly entrenched in local development policy, legislation and practice, is the common assertion that our cities are characterised by patterns of sprawl resulting in excessively costly infrastructure, excessive transportation costs and energy consumption, and environmental damage. The solutions offered relate to curtailing outward expansion of the city using urban edges, increasing densities and promoting public transport with associated increasing densities along public transit routes. The South African government’s subsidised housing programme has accordingly been criticised for providing low-income housing on urban peripheries, far from urban economic and social opportunities, allowing quantity housing targets to be met but at the expense of quality targets in terms of good location. A sustainable housing development cost–benefit model was developed for measuring and comparing the costs and benefits of alternative low-income settlement locations. This model was tested for a number of subsidised housing locations to enable the empirical comparison of locations in terms of the identified sustainability cost-benefit criteria and also to enable further refinement of the model. It was found that there is significant diversity in low-income -

In Search of 1949

In Search of 1949 Vivek Narayanan Program In Historical Studies, UND Department of Anthropology, Stanford University **DRAFT COPY-- PLEASE DO NOT CITE WITHOUT PERMISSION** "Dis poem will not change things: dis poem needs to be changed." --Mutabaruka. The Power and Danger of Looking (From the Natal Daily News, January 14, 1949) Chronicle of Deaths Not Foretold (quotations taken from the testimony of Major George Bestford, District Commandant of Durban, to the Riot Commission) Thursday, January 13 approx. 5:15 p.m.: Harilal Basanth, a 40 year old Indian shop-owner, smashes 14 year old George Madondo's head into a shop window. A "minor disturbance" breaks out. The Police send a van to investigate. 5:25 p.m.: In the busy Victoria Street bus rank, the fight has begun to seriously escalate; Africans want to "hit the Indians whom they alleged had either seriously assaulted or killed a Native youth." A large crowd of Indians gathers in Victoria Street and are prevented from marching to the market by the police. The police send re-inforcements. 6:00 p.m.: Indian men and women throw bricks and other missiles at Africans below. 6:30 p.m.: Some shop windows have been smashed; there are "large numbers of both Europeans and non-Europeans about." The rioters on the street are mainly African, but include some Indians and Europeans. Still, there is not much damage to property at this point. 7 p.m.: Accounts of the event have been carried home to barracks and residential areas; in Cato Manor, buses are stoned. 8:30 p.m.: In Clairwood and the southern part of central Durban, Indian buses are stoned.