Resources Created for Lesson Two

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Louisville Family ; Mary Married Wm. Smith, of Madison County, Ky., and Was the Mother of Colonel John Speed Smith and Grandmother of General Green Clay Smith

— CAPT. JAMES SPEED AND MARY SPENCER SECOND BRANCH. 61 that they we're 'named for their father's sisters. Neither of them survived childhood : Martha, born 1784, died the year following. Sarah, born 1786, died the same year. He also had a son born in Virginia, before the removal to Kentucky, named after his brother, Joseph. This child also died in infancy. An account willbe given of each one of the six surviving children and their descendants. Thomas was the ancestor of the Bardstown family ; John was the ancestor of the Louisville family ; Mary married Wm. Smith, of Madison county, Ky., and was the mother of Colonel John Speed Smith and grandmother of General Green Clay Smith. Her daughter married Tom Fry, and was the mother of General Speed S. Fry and others, all of which willbe particularly named. Elizabeth married Dr. Adam Rankin, whose descendants are in Henderson, Ky. James and Henry have no descend- ants now living. MAJOR THOMAS SPEED. A sketch of the life and times of Major Thomas Speed, first son of Captain James Speed and MarySpencer, would present a history of Kentucky through its most interest- ing period. He was in Kentucky from 1782 until his death in 1842. He was connected with the earliest politi- cal movements, was a Representative in the State Legis- lature and in Congress, and participated in the war of 1812. He was born in Virginia, October 25, 1768, and moved to Kentucky with his father, Captain James Speed, in the fall of 1782. He was then fourteen years of age, and was the eldest of the children The removal of this family to Kentucky was from Charlotte county, Va., which county adjoined Mecklenburg county, where Captain James Speed was born. -

To the William H. Harrison Papers

THE LIB R :\ R Y () F C () N G R E ~ ~ • PRE ~ IDE ~ T S' PAP E R S I ~ D E X ~ E R I E ~ INDEX TO THE William H. Harrison Papers I I I I I I I I I I I I THE LIBRARY OF CONGRESS • PRESIDENTS' PAPERS INDEX SERIES INDEX TO THE William H. Harrison Papers MANUSCRIPT DIVISION • REFERENCE DEPARTMENT LIBRARY OF CONGRESS WASHINGTON : 1960 Library of Congress Cat~log Card Number 60-60012 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, u.s. Government Printing Office Washington 25, D.C.• Price 20 cents Preface THIS INDEX to the William Henry Harrison Papers is a direct result of the wish of the Congress and the President as expressed by Public Law 85-147 dated August 16, 1957, to inspire inforrr..ed patriotism, to provide greater security for the original manuscripts, and to make the Harrison Papers more accessible and useful to scholars and other interested persons. The law authorizes and directs the Librarian of Congress to arrange, microfilm, and index the Papers of the 23 Presidents whose manuscripts are in the Library. An appropriation to carry out the provisions of the law was approved on July 31, 1958, and actual operations began on August 25. The microfilm of the Harrison Papers became available in the summer of 1959. The microfilm of the Harrison Papers and this index are the third micrcfilm and index to be issued in this series. Positive copies of the microfilm may be purchased from the Chief, Photoduplication Service, Library of Congress, Washington 25, D.C. -

'!Baptist Lil[;~ 1Ttr~ - "'1__ R; ~-Filf: L- ,~ ,, Jlplr'.,Jl ~ !

1{tntuc,(y '!Baptist lil[;~_ 1ttr~_- "'1__ r; ~-filf: L- ,~ ,, JlPlr'.,Jl ~ ! . ,~ L, -~-~.J- ""' .,~- •=·· .,. .- " •... -.. ..• ~ 'Vo{ume X'Vl II 'J{gvemher 1993 :!{umber 1 HISTORICAL COMMISSION 1993-1994 Chainnan Tenns Ending 1993 Southwestern Region: Mrs. Pauline Stegall, P.O. Box 78, Salem 42078 (unex) Central Region: Thomas Wayne Hayes, 4574 South Third Street, Louisville 40214 State-at-Large: Larry D. Smith, 2218 Wadsworth Avenue, Louisville 40204 Tenns Ending 1994 Southern Region: Ronnie R. Forrest, 612 Stacker Street, Lewisburg 42256 South Central Region: Mrs. Jesse Sebastian, 3945 Somerset Road, Stanford40484 Northeastern Region: Stanley R. Williams, Cannonsburg First Baptist Church, 11512 Midland Trail, Ashland41102 (unex) Tenns Ending 1995 Western Region: Carson Bevil, 114 North Third Street, Central City 42330 Southeastern Region: Chester R. Young, 758 Becks Creek Alsile Road, Williamsburg 40769-1805 North Central Region: Terry Wilder, P.O. Box 48, Burlington 41005 (unex) Pennanent Members President of Society: Ronnie Forrest, 612 Stacker Street, Lewisburg 42256 Treasurer: Barry G. Allen, Business Manager, KBC, P.O. Box 43433, Louisville 40253-0433 Kentucky Member of SBC Historical Commission: Doris Yeiser, 245 Salisbury Square, Louisville 40207 Curator & Archivist: Doris Yeiser, P.O. Box 43433, Louisville 40253-0433 Librarian, Southern Baptist Theological Seminary: Ronald F. Deering, 2825 Lexington Road, Louisville 40280 Ex Officio Members William W. Marshall, Executive Secretary-Treasurer, Kentucky Baptist Convention, P.O. Box 43433, Louisville 40253-0433 Marv Knox, Editor, Western Recorder, Kentucky Baptist Convention, P.O. Box 43433, Louisville 40253-0433 Editor Doris B. Yeiser, Archivist, Kentucky Baptist Convention, P.O. Box 43433, Louisville 40253-0433 Newsletter published by Kentucky Baptist Historical Commission & Archives, 10701 Shelbyville Road, Louisville, Kentucky 40243. -

Biography from History of Clay Co., Indiana, Vol. II

<CENTER> <P> Biography from History of Clay Co., Indiana, Vol. II, <BR> au: William Travis, publ. 1909 <P></CENTER><CENTER><H3>Isaac Shelby HARGER</H3></CENTER> <PRE> Prominent among the representatives of industrial interests in Brazil is numbered Isaac Shelby Harger, a painter and a decorator with an extensive and growing business. His careful management, combined with his unwearied industry, constitute important elements in the success which he is now enjoying and have won for him a place among the substantial residents of his adopted city. He was in Bardstown, Nelson county, Kentucky, January 11, 1846, his birthplace being one of the historic points of the south and especially identified with the early founding of the Catholic church in that section of the country. In the earlier portion of the nineteenth century Bardstown had acquired such a standing as a center of education and culture as to he christened by Henry Clay the “Athens of the West.” In 1774 Bardstown was first settled as Salem, but when it was incorporated by the Virginia legislature four years later it adopted its present name. Its original settlers were English Catholics, and one explanation of its name is that among the earliest and most prominent were the Bairds. Later came the Jesuit missionaries, and the Sisters of Nazareth founded a seminary for the higher education of gentlemen’s daughters.” The town also became a large manufacturing center, and its importance as a center of industry and culture induced the pope to create it an episcopal see, the first west of the Alleghany mountains. -

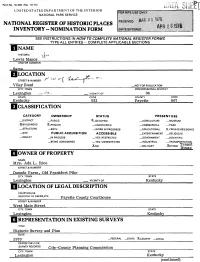

Nomination Form Location

Form No. 10-300 (Rev. 10-74) UfV UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY -- NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOWTO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS ______________TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS______ BNAME HISTORIC k LK^ Lewis Manor__________________________________________ AND/OR COMMON SflTOPi__________________________________ ________________________ LOCATION .&f^ ^ STREET & NUMBER ^ 1 Viley Road____ NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY, TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Lexington VICINITY OF 06 STATE CODE COUNTY CODE Kentucky 021 Fayette 067 CLASSIFICATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE —DISTRICT —PUBLIC ^-OCCUPIED _AGRICULTURE —MUSEUM X_BUILDING(S) X-PRIVATE —UNOCCUPIED —COMMERCIAL _PARK —STRUCTURE BOTH —WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL X-PRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS _OBJECT _IN PROCESS —YES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED — YES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION X.NQ —MILITARY XOTHER: ^^ OWNER OF PROPERTY NAME Mrs. Ada L, Rice STREET & NUMBER Panada Farm, Old Frankfort Pike CITY, TOWN STATE Lexington VICINITY OF Kentucky LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE, REGISTRY OF DEEDS,ETC, Fayette County Courthouse STREET & NUMBER West Main Street CITY. TOWN STATE Lexington Kentucky TITLE Historic Survey and Plan DATE 1970 .FEDERAL STATE X.COUNTY LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS City-County Planning Commission CITY, TOWN STATE Lexington Kentucky (continued) DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE —EXCELLENT _DETERIORATED —UNALTERED X.ORIGINALSITE —GOOD —RUINS X.ALTERED —MOVED DATE_____ JCFAIR _UNEXPOSED DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE The house known as Lewis Manor is situated on a gentle knoll on Viley Pike off Leestown Pike, a major thoroughfare into Lexington (see photo 1). Rolling hills characterize the countryside and the area viewed from the house is presently all in farmland. -

1 CONTENTS the REGISTER Listed Below Are the Contents of the Register from the First Issue in 1903 to the Current Issue in A

CONTENTS THE REGISTER OF THE KENTUCKY HISTORICAL SOCIETY Listed below are the contents of the Register from the first issue in 1903 to the current issue in a searchable PDF format. VOLUME 1 Number One, January 1903 A New Light on Daniel Boone‘s Ancestry Mrs. Jennie C. Morton ...................................................................... 11 Kentucky‘s First Railroad, which was the First One West of the Allegheny Mountains ........................................................................ 18 Fort Hill ........................................................................................... 26 Address of Hon. John A. Steele, Vice President, before Kentucky Historical Society, February 11, 1899 ............................... 27 The Seal of Kentucky ........................................................................ 31 Before Unpublished Copy of a Letter from Gen. Ben Logan to Governor Isaac Shelby Benjamin Logan ............................................................................... 33 Counties in Kentucky and Origin of their Names Published by Courtesy of the Geographer of the Smithsonian Institute ........................................................................................... 34 Paragraphs ....................................................................................... 38 The Kentucky River and Its Islands Resident of Frankfort, Kentucky ....................................................... 40 Department of Genealogy and History Averill.............................................................................................. -

Download a PDF Version of the Guide to African American Manuscripts

Guide to African American Manuscripts In the Collection of the Virginia Historical Society A [Abner, C?], letter, 1859. 1 p. Mss2Ab722a1. Written at Charleston, S.C., to E. Kingsland, this letter of 18 November 1859 describes a visit to the slave pens in Richmond. The traveler had stopped there on the way to Charleston from Washington, D.C. He describes in particular the treatment of young African American girls at the slave pen. Accomack County, commissioner of revenue, personal property tax book, ca. 1840. 42 pp. Mss4AC2753a1. Contains a list of residents’ taxable property, including slaves by age groups, horses, cattle, clocks, watches, carriages, buggies, and gigs. Free African Americans are listed separately, and notes about age and occupation sometimes accompany the names. Adams family papers, 1698–1792. 222 items. Mss1Ad198a. Microfilm reels C001 and C321. Primarily the papers of Thomas Adams (1730–1788), merchant of Richmond, Va., and London, Eng. Section 15 contains a letter dated 14 January 1768 from John Mercer to his son James. The writer wanted to send several slaves to James but was delayed because of poor weather conditions. Adams family papers, 1792–1862. 41 items. Mss1Ad198b. Concerns Adams and related Withers family members of the Petersburg area. Section 4 includes an account dated 23 February 1860 of John Thomas, a free African American, with Ursila Ruffin for boarding and nursing services in 1859. Also, contains an 1801 inventory and appraisal of the estate of Baldwin Pearce, including a listing of 14 male and female slaves. Albemarle Parish, Sussex County, register, 1721–1787. 1 vol. -

Green Clay Smith

University of Oklahoma College of Law University of Oklahoma College of Law Digital Commons American Indian and Alaskan Native Documents in the Congressional Serial Set: 1817-1899 6-4-1880 Green Clay Smith. Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.ou.edu/indianserialset Part of the Indian and Aboriginal Law Commons Recommended Citation H.R. Rep. No. 1624, 46th Cong., 2nd Sess. (1880) This House Report is brought to you for free and open access by University of Oklahoma College of Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in American Indian and Alaskan Native Documents in the Congressional Serial Set: 1817-1899 by an authorized administrator of University of Oklahoma College of Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 46TH CONGREss, } HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES. J REPORT 2d Session. ~ N o.1624. GREEN CLAY SMITH. JosE 4, 1880.-Laid on the table and orderetl to be printed. 1\fr. RoBINSON, from the Committee on the Judiciary, submitted the fol lowing REPORT· [To accompany bill H. R. 4069.] The Committee on the J~tdiciary, to whom was referred the bill (H. R. 4069) providing for the relief of Green Clay Smith, and for other purposes, have had the sanw ~tnder consideration, and now sub'mit the following report: Green Clay Smith was appointed superintendent of Indian affairs in Montana Territory, and as such officer gave a bond with sureties, on the 30th day of April, 1867, in a penalty of $50,000, to the United States. Upon settlement of his accounts he was found to be in default to the government in the sum of $28,854.58. -

Robert A. Genheimer

BANDING, CABLE, AND CAT’S-EYE: AN ARCHAEOLOGICAL AND HISTORICAL EXAMINA- TION OF NINETEENTH CENTURY FACTORY-MADE CINCINNATI-AREA YELLOW WARE Robert A. Genheimer Abstract Cincinnati’s contribution to the nineteenth century American yellow ware market has received little attention in the literature. Like East Liverpool, Ohio, Cincinnati in the 1840s attracted a significant number of British-born, and Staffordshire-trained potters. Between ca. 1842 and ca. 1870, at least a half-dozen Cincinnati potteries pro- duced large quantities of yellow ware and Rockingham in factory settings. In an effort to better understand this production, an assemblage of 289 discrete yellow ware vessels recovered from six major urban archaeology pro- jects in Cincinnati, Ohio and Covington, Kentucky is carefully examined. The majority of vessels originate from nineteenth century privy shafts, many of which exhibit well-dated depositional horizons beginning in the 1840s. A broad range of vessel types is identified including chamber pots, bowls, pitchers, spittoons, plates, and unspeci- fied hollow ware. While a significant proportion of the vessels are undecorated, numerous slip decorations, including common cable, cat’s eye, annular banding, slip trailing, dendrites, and broad slip bands are identified. Only a very small number of sample vessels are marked (with a maker’s mark), however at least six-dozen un- marked vessels from Covington Pottery wasters allow for attribution to William Bromley. Although a number of privy shafts producing yellow ware are well dated, a broad range of sample vessels recovered from the lowest levels of those features indicates that much of the full range of decoration was already present by the time of dep- osition. -

History of Kentucky

A HISTORY OF KENTUCKY ELIZABETH SHELBY KINKEAD MARS HILL PRESS Lexington, KY (859) 271-3646 ORIGINALLY PUBLISHED BY: AMERICAN BOOK COMPANY COPYRIGHT, 1896, 1909, 1919 A History of Kentucky was first published in many stories of civil rights and suffrage that can 1896. It is reproduced here to give the modern supplement a later history, this volume was written teacher the option of a text with a “fresh, new before those themes were introduced to Kentucky approach.” Compared to the revisionist histories and is not “improved” by weaving modern themes that have been popular for the last 20 years, this old into earlier periods. volume tells history through the eyes of one who The 20th century created a completely lived it and told it just as she saw it and had it told to different Kentucky. The themes from those years her by her parents. are more complicated and, therefore, difficult to To the extent that personality and style affect teach on a Jr. High level. This history is best used to the volume, Mrs. Kinkead brings the late 19th tell the simple story of Kentucky’s birth and her early century (New Kentucky at the time of the writing) years through the Civil War. love of the state, patriotism and altruism to the story. May God use this reprint to create a love of Absent from this volume is the attempt to the Commonwealth in her future citizens and include all races and gender equally. While there are leaders. - Billy Henderson THIS PRINTING BASED ON THE REVISED EDITION PUBLISHED IN 1919. -

To the Southern Baptists

TO THE SOUTHERN BAPTISTS. In order to increase our circulation, we will send specimen copies of KIND WORDS, or of THE GEM, or of the QUARTERLIES or LEAFLETS, to those desiring to use or introduce them. Wo solicit the patronage of all Baptist Sunday Schools and families, feeling sure that the lessons of KIND WORDS are well adapted to the capacity of children, and that its reading matter will be advantageous to them. THE LESSONS will be decidedly improved, and will include THREE QRADES: 1. EXPLANATIONS AND QUESTIONS WITHOUT ANSWERS for the elder scholars. 2. QUESTIONS AND*ANSWERS, for intermediate scholars. 3. LESSON STORY AND QUESTIONS AND ANSWERS for the youngest scholars. These lessons will have all the other usual departments also, and will be unexcelled by any lessons for Sunday School scholars published. The reading matter, pictures, paper and printing will be unsurpassed. The Mission, Denom inational and'Sunday School Instruction features of the paper will be maintained. Its missionary correspondence, and contributions from distinguished correspond ents, will be a marked feature. It will continue its advocacy of missions, perance, and the interests of the Southern Baptist Convention and its Boi * . But its chief aim will be TO LEAD THE YOUNG TO JESUS and train them fo uis service. The price of these publications has been reduced, and the Weekly may now be had, in clubs, tor fifty cents a year, and the Semi-Monthly for twenty-five cents a year. THE QUARTERLY—Containing the lessons for each quarter of the year, with other helps for teachers and scholars, per annum, twenty cents. -

Clay Lancaster's Kentucky: Architectural Photographs of a Preservation Pioneer

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Architecture University Press of Kentucky 3-30-2007 Clay Lancaster's Kentucky: Architectural Photographs of a Preservation Pioneer James D. Birchfield University of Kentucky, [email protected] Click here to let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Thanks to the University of Kentucky Libraries and the University Press of Kentucky, this book is freely available to current faculty, students, and staff at the University of Kentucky. Find other University of Kentucky Books at uknowledge.uky.edu/upk. For more information, please contact UKnowledge at [email protected]. Recommended Citation Birchfield, James .,D "Clay Lancaster's Kentucky: Architectural Photographs of a Preservation Pioneer" (2007). Architecture. 6. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/upk_architecture/6 CLAY LANCASTER'S KENTUCKY This page intentionally left blank CLAY LANCASTER'S KENTUCKY Architectural Photographs of a Preservation Pioneer , James D. Birchfield Foreword by Roger W. Moss The University Press of Kentucky Publication ofthis volume was made possible in part by a Library ofCongress Cataloging-in-Publication Data grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities. Birchfield,]ames D. Clay Lancaster's Kentucky: architectural photographs ofa Photograph on p. II by Lisa Basch, courtesy ofWarwick Foundation. preservation pioneer / James D. Birchfield; foreword by All other photographs courtesy ofthe University of Kentucky Roger W. Moss. Library's Special Collections. p.cm. ISBN-IJ: 978-0-8131-2421-6 (hardcover: alk. paper) Copyright