Robert A. Genheimer

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Louisville Family ; Mary Married Wm. Smith, of Madison County, Ky., and Was the Mother of Colonel John Speed Smith and Grandmother of General Green Clay Smith

— CAPT. JAMES SPEED AND MARY SPENCER SECOND BRANCH. 61 that they we're 'named for their father's sisters. Neither of them survived childhood : Martha, born 1784, died the year following. Sarah, born 1786, died the same year. He also had a son born in Virginia, before the removal to Kentucky, named after his brother, Joseph. This child also died in infancy. An account willbe given of each one of the six surviving children and their descendants. Thomas was the ancestor of the Bardstown family ; John was the ancestor of the Louisville family ; Mary married Wm. Smith, of Madison county, Ky., and was the mother of Colonel John Speed Smith and grandmother of General Green Clay Smith. Her daughter married Tom Fry, and was the mother of General Speed S. Fry and others, all of which willbe particularly named. Elizabeth married Dr. Adam Rankin, whose descendants are in Henderson, Ky. James and Henry have no descend- ants now living. MAJOR THOMAS SPEED. A sketch of the life and times of Major Thomas Speed, first son of Captain James Speed and MarySpencer, would present a history of Kentucky through its most interest- ing period. He was in Kentucky from 1782 until his death in 1842. He was connected with the earliest politi- cal movements, was a Representative in the State Legis- lature and in Congress, and participated in the war of 1812. He was born in Virginia, October 25, 1768, and moved to Kentucky with his father, Captain James Speed, in the fall of 1782. He was then fourteen years of age, and was the eldest of the children The removal of this family to Kentucky was from Charlotte county, Va., which county adjoined Mecklenburg county, where Captain James Speed was born. -

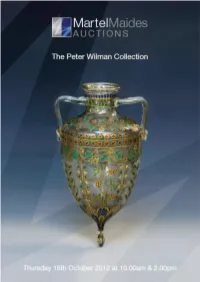

The Wilman Collection

The Wilman Collection Martel Maides Auctions The Wilman Collection Martel Maides Auctions The Wilman Collection Martel Maides Auctions The Wilman Collection Lot 1 Lot 4 1. A Meissen Ornithological part dessert service 4. A Derby botanical plate late 19th / early 20th century, comprising twenty plates c.1790, painted with a central flower specimen within with slightly lobed, ozier moulded rims and three a shaped border and a gilt line rim, painted blue marks square shallow serving dishes with serpentine rims and and inscribed Large Flowerd St. John's Wort, Derby rounded incuse corners, each decorated with a garden mark 141, 8½in. (22cm.) diameter. or exotic bird on a branch, the rims within.ects gilt £150-180 edges, together with a pair of large square bowls, the interiors decorated within.ects and the four sides with 5. Two late 18th century English tea bowls a study of a bird, with underglaze blue crossed swords probably Caughley, c.1780, together with a matching and Pressnumern, the plates 8¼in. (21cm.) diameter, slop bowl, with floral and foliate decoration in the dishes 6½in. (16.5cm.) square and the bowls 10in. underglaze blue, overglaze iron red and gilt, the rims (25cm.) square. (25) with lobed blue rings, gilt lines and iron red pendant £1,000-1,500 arrow decoration, the tea bowls 33/8in. diameter, the slop bowl 2¼in. high. (3) £30-40 Lot 2 2. A set of four English cabinet plates late 19th century, painted centrally with exotic birds in Lot 6 landscapes, within a richly gilded foliate border 6. -

Here to See Ceramics in the U.S

www.ceramicsmonthly.org Editorial [email protected] telephone: (614) 895-4213 fax: (614) 891-8960 editor Sherman Hall assistant editor Renee Fairchild assistant editor Jennifer Poellot publisher Rich Guerrein Advertising/Classifieds [email protected] (614) 794-5809 fax: (614) 891-8960 [email protected] (614) 794-5866 advertising manager Steve Hecker advertising services Debbie Plummer Subscriptions/Circulation customer service: (614) 794-5890 [email protected] marketing manager Susan Enderle Design/Production design Paula John graphics David Houghton Editorial, advertising and circulation offices 735 Ceramic Place Westerville, Ohio 43081 USA Ceramics Monthly (ISSN 0009-0328) is published monthly, except July and August, by The American Ceramic Society, 735 Ceramic Place, Westerville, Ohio 43081; www.ceramics.org. Periodicals postage paid at Westerville, Ohio, and additional mailing offices. Opinions expressed are those of the contributors and do not necessarily represent those of the editors or The Ameri can Ceramic Society. subscription rates: One year $32, two years $60, three years $86. Add $25 per year for subscriptions outside North America. In Canada, add 7% GST (registration number R123994618). back issues: When available, back issues are $6 each, plus $3 shipping/ handling; $8 for expedited shipping (UPS 2-day air); and $6 for shipping outside North America. Allow 4-6 weeks for delivery. change of address: Please give us four weeks advance notice. Send the magazine address label as well as your new address to: Ceramics Monthly, Circulation De partment, PO Box 6136, Westerville, OH 43086-6136. contributors: Writing and photographic guidelines are available on request. Send manuscripts and visual sup port (slides, transparencies, etc.) to Ceramics Monthly, 735 Ceramic PI., Westerville, OH 43081. -

Oriental & European Ceramics & Glass

THIRD DAY’S SALE WEDNESDAY 24th JANUARY 2018 ORIENTAL & EUROPEAN CERAMICS & GLASS Commencing at 10.00am Oriental and European Ceramics and Glass will be on view on: Friday 19th January 9.00am to 5.15pm Saturday 20th January 9.00am to 1.00pm Sunday 21st January 2.00pm to 4.00pm Monday 22nd January 9.00am to 5.15pm Tuesday 23rd January 9.00am to 5.15pm Limited viewing on sale day Measurements are approximate guidelines only unless stated to the contrary Enquiries: Andrew Thomas Enquiries: Nic Saintey Tel: 01392 413100 Tel: 01392 413100 Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] 661 662 A large presentation wine glass and a pair of wine glasses Two late 18th century English wine glasses, one similar the former with bell shaped bowl engraved with the arms of and an early 19th century barrel-shaped tumbler the first Weston, set on a hollow knopped stem and domed fold over two with plain bowls and faceted stems, 13.5 cm; the third foot, 27 cm high, the pair each with rounded funnel shaped engraved with floral sprays and on faceted stem, 14 cm; the bowl engraved with an eagle’s head set on a double knopped tumbler engraved with urns, paterae and swags with the stem and conical foot, 23 cm high. initials ‘GS’,11 cm (4). *£200 - 250 *£120 - 180 663 A George Bacchus close pack glass paperweight set with various multi coloured canes and four Victoria Head silhouettes, circa 1850, 8 cm diameter, [top polished]. *£300 - 500 664 665 A Loetz Phanomen glass vase of A Moser amber crackled glass vase of twelve lobed form with waisted neck shaped globular form, enamelled with and flared rim, decorated overall with a a crab, a lobster and fish swimming trailed and combed wave design, circa amongst seaweed and seagrass, circa 1900-05, unmarked, 19 cm high. -

March 2007 Volume 8 Issue 1 T RENTON POTTERIES

March 2007 Volume 8 Issue 1 T RENTON POTTERIES Newsletter of the Potteries of Trenton Society Mayer’s Pottery and a Portneuf /Quebec Puzzle Jacqueline Beaudry Dion and Jean-Pierre Dion Spongeware sherds found in the dump site ENT PROCESS/FEB 1st 1887” and deco- of Mayer’s Arsenal Pottery in Trenton, rated with the cut sponge chain motif so New Jersey, revealed the use of several mo- popular in England and Scotland. Many tifs including the chain or rope border that of the sponge decorated ware found in was used later in Beaver Falls, Pennsyl- the Portneuf-Quebec area (and thus vania. Those cut sponge wares, when found called Portneuf wares) were actually in the Quebec area, are dubbed “Portneuf” made in Scotland, especially those de- and generally attributed to the United picting cows and birds. Finlayson Kingdom, in particular to Scotland. The (1972:97) naturally presumed the barrel mystery of the Portneuf chain design iron- had been produced in Scotland, al- stone barrel (Finlayson, 1972:97 ) is no though his research in England and more a puzzle: a final proof of its United Scotland failed to show any record of States origin is provided by a patent such a name or such a patent. “Could granted to J. S. Mayer in 1887. this J. S. Mayer,” he wrote, “have been associated with the John Thomson Ann- he small ironstone china barrel field Pottery [Glasgow, Scotland]? Per- T found in the Province of Quebec haps his process was used in the Thom- and illustrated here (Figure 1), is ap- son Pottery. -

To the William H. Harrison Papers

THE LIB R :\ R Y () F C () N G R E ~ ~ • PRE ~ IDE ~ T S' PAP E R S I ~ D E X ~ E R I E ~ INDEX TO THE William H. Harrison Papers I I I I I I I I I I I I THE LIBRARY OF CONGRESS • PRESIDENTS' PAPERS INDEX SERIES INDEX TO THE William H. Harrison Papers MANUSCRIPT DIVISION • REFERENCE DEPARTMENT LIBRARY OF CONGRESS WASHINGTON : 1960 Library of Congress Cat~log Card Number 60-60012 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, u.s. Government Printing Office Washington 25, D.C.• Price 20 cents Preface THIS INDEX to the William Henry Harrison Papers is a direct result of the wish of the Congress and the President as expressed by Public Law 85-147 dated August 16, 1957, to inspire inforrr..ed patriotism, to provide greater security for the original manuscripts, and to make the Harrison Papers more accessible and useful to scholars and other interested persons. The law authorizes and directs the Librarian of Congress to arrange, microfilm, and index the Papers of the 23 Presidents whose manuscripts are in the Library. An appropriation to carry out the provisions of the law was approved on July 31, 1958, and actual operations began on August 25. The microfilm of the Harrison Papers became available in the summer of 1959. The microfilm of the Harrison Papers and this index are the third micrcfilm and index to be issued in this series. Positive copies of the microfilm may be purchased from the Chief, Photoduplication Service, Library of Congress, Washington 25, D.C. -

'!Baptist Lil[;~ 1Ttr~ - "'1__ R; ~-Filf: L- ,~ ,, Jlplr'.,Jl ~ !

1{tntuc,(y '!Baptist lil[;~_ 1ttr~_- "'1__ r; ~-filf: L- ,~ ,, JlPlr'.,Jl ~ ! . ,~ L, -~-~.J- ""' .,~- •=·· .,. .- " •... -.. ..• ~ 'Vo{ume X'Vl II 'J{gvemher 1993 :!{umber 1 HISTORICAL COMMISSION 1993-1994 Chainnan Tenns Ending 1993 Southwestern Region: Mrs. Pauline Stegall, P.O. Box 78, Salem 42078 (unex) Central Region: Thomas Wayne Hayes, 4574 South Third Street, Louisville 40214 State-at-Large: Larry D. Smith, 2218 Wadsworth Avenue, Louisville 40204 Tenns Ending 1994 Southern Region: Ronnie R. Forrest, 612 Stacker Street, Lewisburg 42256 South Central Region: Mrs. Jesse Sebastian, 3945 Somerset Road, Stanford40484 Northeastern Region: Stanley R. Williams, Cannonsburg First Baptist Church, 11512 Midland Trail, Ashland41102 (unex) Tenns Ending 1995 Western Region: Carson Bevil, 114 North Third Street, Central City 42330 Southeastern Region: Chester R. Young, 758 Becks Creek Alsile Road, Williamsburg 40769-1805 North Central Region: Terry Wilder, P.O. Box 48, Burlington 41005 (unex) Pennanent Members President of Society: Ronnie Forrest, 612 Stacker Street, Lewisburg 42256 Treasurer: Barry G. Allen, Business Manager, KBC, P.O. Box 43433, Louisville 40253-0433 Kentucky Member of SBC Historical Commission: Doris Yeiser, 245 Salisbury Square, Louisville 40207 Curator & Archivist: Doris Yeiser, P.O. Box 43433, Louisville 40253-0433 Librarian, Southern Baptist Theological Seminary: Ronald F. Deering, 2825 Lexington Road, Louisville 40280 Ex Officio Members William W. Marshall, Executive Secretary-Treasurer, Kentucky Baptist Convention, P.O. Box 43433, Louisville 40253-0433 Marv Knox, Editor, Western Recorder, Kentucky Baptist Convention, P.O. Box 43433, Louisville 40253-0433 Editor Doris B. Yeiser, Archivist, Kentucky Baptist Convention, P.O. Box 43433, Louisville 40253-0433 Newsletter published by Kentucky Baptist Historical Commission & Archives, 10701 Shelbyville Road, Louisville, Kentucky 40243. -

Rockingham 1745-1842 Datasheet

TITLE INFORMATION Tel: +1 212 645 1111 Email: [email protected] Web: https://www.accartbooks.com/us Rockingham 1745-1842 Alwyn Cox Angela Cox ISBN 9781851493722 Publisher ACC Art Books Binding Hardback Territory USA & Canada Size 8.5 in x 10.98 in Pages 432 Pages Illustrations 146 color, 453 b&w Price $89.50 A new, detailed, comprehensive and fully illustrated account of the Rockingham Pottery's history and wares Illustrates the entire range of products, both pottery and porcelain, emphasising shapes, types of decoration and means of identification Many pieces shown for the first time, mainly from private collections Written by acknowledged authorities on the subject This new, comprehensive and well-illustrated account of the Rockingham Pottery, one of England's major nineteenth century porcelain manufactories, traces its unusual development and diverse wares from 1745, when it was founded, to its closure almost a century later. Archaeological evidence has been used to identify eighteenth century slip-decorated pottery, fine unmarked creamware, pearlware and the early products of the following century. Characteristic shapes and types of decoration are illustrated, including the complete range of transfer-printed designs on pottery. In porcelain, for which the Rockingham Works is justly renowned, its tea and dessert services, including those made for royalty and nobility, are described and illustrated, as are figures and the many ornamental items. All known factory marks are shown and guidance is given to help collectors avoid spurious wares. Many of the pieces illustrated are in private collections. They vary from items of extraordinary beauty and richness to more everyday wares. -

Mexborough's Rich Pottery History

A Town of Potters charged with “riot and assault” and John Wragg was charged Mexborough’s rich with stealing a teapot, ewer, jug, pottery history bowls, cups and saucers from Mexborough Old Pottery. The earliest documented pottery The Rock Pottery was owned in Mexborough dates from the by the industrialist John Reed. late 18th century. Mexborough In 1859 he commissioned Old Pottery, the Rock Pottery, emerging local sculptor Robert Emery’s Pottery and Alfred Glassby to produce a decorative Baguley’s Decorating Business arch for his garden. The arch can were all based in the town. now be seen in the grounds of Mexborough Almshouses. During the 19th century hundreds of potters lived and worked in This rich history is kept alive by Mexborough. They formed an collectors and enthusiasts. One active part of the community but of the leading local pottery occasionally found themselves in experts is Mexborough’s own trouble. In 1804 Ralph Whitaker, Graham Oliver, former guitarist a potter from Mexborough, was for heavy metal band Saxon. 1854 Ordnance Survey Map Site of Mexborough Rock Pottery Beyond Elsecar Colliery. The Don Pottery exported pots from Swinton Rockingham across the world. Joseph Green, The Don Pottery whose father owned the pottery, regularly visited Rio de Janeiro as a in Swinton merchant in the early 19th century. The Greens went bankrupt in Rockingham Pottery in Swinton 1834 and the Barkers then took is by far the best known of over the Don Pottery. Samuel all Yorkshire potteries and Barker, from Staffordshire, also ran the porcelain products made the Mexborough Old Pottery and there are amongst the finest made a great financial success ever produced. -

Site-22A-Arsenal-Pottery-With-Industrial-Census.Pdf

Arsenal Pottery # 22A Other Names Joseph Mayer's Arsenal Pottery; Mayer Brothers; Arsenal; Mayer Arsenal; Joseph Mayer; Mayer Company; Mayer Pottery Company; Mayer Manufacturing Company Present Day Municipality City of Trenton Historic Municipality City of Trenton Historic Location Third Street corner of Temple Street; Third Street and Schenck Street Years in Operation 1876- c.1905 Owners/Operators Joseph and James Mayer (1876-1893) [Mayer Pottery Company (1876-1889), Mayer Arsenal Pottery Company (1889-1893)]; Joseph Mayer, Isaac Davis and Michael Sewell (1893-c.1905) [Mayer Pottery Manufacturing Company (1893- c. 1905)] PRODUCTS Tableware Garden Ceramics Rockingham Other Hardware Art Ceramics Toilet Sets Sanitary ware Hotel China Electrical porcelain ADDITIONAL PRODUCT INFORMATION Rockingham and brown stoneware, fancy flower pots and hanging baskets, hanging logs, stumps and pedestals, stove collars, yellowware, majolica (Mains & Fitzgerald 1877); Rockingham and yellowware, including tea and coffee pots, jars, spittoons, dishes, bowls, pans, etc., also majolica ware (Industries of New Jersey 1882:178); white granite, decorated biscuit, painted and majolica ware … jugs, cuspidors and jardinieres a specialty (Potters National Union 1893) majolica jugs, Toby pitchers, teapots, plates, bowls, creamers, vases, jardinieres and spittoons (Snyder and Bockol 1994:139; Snyder 2005:42-43) REFERENCES Mains, Bishop W. and Thomas F. Fitzgerald. 1877-1879. "Mains and Fitzgerald's Trenton, Chambersburg and Millham Directory: Containing the Names of the Citizens, Statistical Business Report, Historical Sketches, a List of the Public and Private Institutions, Together with National, State, County, and City Government." Bishop W. Mains & Thomas F. Fitzgerald, Trenton, New Jersey. Wednesday, April 10, 2013 Arsenal Pottery # 22A Young, Jennie J. -

Resources Created for Lesson Two

Resources Created for Lesson Plan Two: • Biographies of Famous Kentuckians o Abraham Lincoln o Henry Clay o Cassius Clay o John G. Fee o Joshua Speed o Mary Todd Lincoln • Slavery Timeline • Lincoln’s Quotes on Slavery • Emancipation Proclamation Resource Document • Kentuckians Views on Slavery • Definitions of Slavery • “That All Mankind Should be Free” Article • Lincoln-Douglas Debates Web link North American Slavery Timeline • 1441 Portugal begins slave trade between Africa and Europe. • 1520 Disease decimates Native Americans, enslaved Africans imported as replacements. • 1581 First enslaved Africans arrive in Florida. • 1607 Jamestown settled. • 1619 First Africans arrive at Jamestown. • 1642 Virginia law makes it illegal to assist escaping slaves. • 1661-1700 slave codes become increasing prohibitive, eventually giving life/death to owners/state. • 1751 Christopher Gist and Dr. Thomas Walker, accompanied by an African American servant, explore Kentucky. • 1770 Crispus Attucks, freed/escaped slave: first casualty of the American Revolution • 1775 Daniel Boone accompanied by an African American servant who may have served as his guide, explores Kentucky African Americans fighting in the American Revolution: • 4/18/1775 Lexington and Concord • 6/16/1775 Bunker Hill • 7/9/1775 George Washington issues a command prohibiting further enlistment of African Americans. • 11/12/1775 Lord Dunmore offers freedom to escaped slaves willing to enlist in the British Army. • 12/30/1775 George Washington eases the ban. • Between 4,000 and 6,000 African Americans serve in the Revolutionary Army— mostly in integrated units • 14,000 African Americans leave with the British after their defeat • 100,000 (estimated) African Americans use the war as an opportunity to escape enslavement, many escape west to unsettled lands such as Kentucky. -

Albert Amor Ltd

ALBERT AMOR LTD. RECENT ACQUISITIONS AUTUMN 2019 37 BURY STREET, ST JAMES’S, LONDON SW1Y 6AU Opening Times Monday to Friday 10.00am - 5.30pm Saturday and Sunday by appointment Telephone: 0207 930 2444 www.ALBERTAMOR.co.uk Foreword I am delighted this autumn to present a catalogue of our recent acquisitions, the largest such catalogue we have issued for some time, and with a great variety of 18th and 19th century pieces. Amongst these, there are many items with an illustrious provenance, and many that have been widely illustrated over the years. We were fortunate to acquire a fine group of early Derby and important Rockingham from the collection of the late Dennis Rice, many pieces illustrated and discussed in his various books, including the rare mug, number 39, which he had acquired from us, and the unrecorded Rockingham horse, number 85. From a distinguished American collection we offer a superb pair of Bow models of Kestrels, a rare Chelsea group and two Chelsea figures, formerly in the celebrated collection of Irwin Untermyer at the Metropolitan Museum in New York. The rare early Chelsea beaker, number 7, was in the T D Barclay Collection, and the very unusual Chelsea vase, number 16, was formerly in the John Hewett Collection, and exhibited here in 1997. A great element of the history of Albert Amor Limited is our reputation for helping to form collections, and then in later years be called upon to help curate and disperse those collections again. For twenty five years I have been fortunate to work with Rt.