Journal of Arts & Humanities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Public Perceptions of Mt. Merapi and Mt. Agung

SIT Graduate Institute/SIT Study Abroad SIT Digital Collections Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection SIT Study Abroad Spring 2019 There She Blows: Public Perceptions of Mt. Merapi and Mt. Agung Trey Atticus Spadone SIT Study Abroad Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcollections.sit.edu/isp_collection Part of the Asian Studies Commons, Civic and Community Engagement Commons, Emergency and Disaster Management Commons, Organizational Communication Commons, Pacific Islands Languages and Societies Commons, Place and Environment Commons, and the Volcanology Commons Recommended Citation Spadone, Trey Atticus, "There She Blows: Public Perceptions of Mt. Merapi and Mt. Agung" (2019). Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection. 3165. https://digitalcollections.sit.edu/isp_collection/3165 This Unpublished Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the SIT Study Abroad at SIT Digital Collections. It has been accepted for inclusion in Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection by an authorized administrator of SIT Digital Collections. For more information, please contact [email protected]. There She Blows: Public Perceptions of Mt. Merapi and Mt. Agung Trey Atticus Spadone Project Advisor: Rose Tirtalistyani SIT Study Abroad Indonesia: Arts, Religion, and Social Change Spring 2019 PUBLIC PERCEPTIONS OF MT. MERAPI AND MT. AGUNG 2 Table of Contents Acknowledgments ..................................................................................................................................................................... -

Philippine Music Instruments CORAZON CANAVE-DIOQUINO Music Instruments, Mechanisms That Produce Sounds, Have Been Used for Various Purposes

Philippine Music Instruments CORAZON CANAVE-DIOQUINO Music instruments, mechanisms that produce sounds, have been used for various purposes. In earlier times they were also used as an adjunct to dance or to labor. In later civilizations, instrumental music was used for entertainment. Present day musicological studies, following the Hornbostel-Sachs classification, divide instruments into the following categories: idiophones, aerophones, chordophones, and membranophones. Idiophones Instruments that produce sound from the substance of the instrument itself (wood or metal) are classified as idiophones. They are further subdivided into those that are struck, scraped, plucked, shaken, or rubbed. In the Philippines there are metal and wooden (principally bamboo) idiophones. Metal idiophonse are of two categories: flat gongs and bossed gongs. Flat gongs made of bronze, brass, or iron, are found principally in the north among the Isneg, Tingguian, Kalinga, Bontok, Ibaloi, Kankanai, Gaddang, Ifugao, and Ilonggot. They are most commonly referred to as gangsa . The gongs vary in sized, the average are struck with wooden sticks, padded wooden sticks, or slapped with the palm of the hand. Gong playing among the Cordillera highlanders is an integral part of peace pact gatherings, marriages, prestige ceremonies, feasts, or rituals. In southern Philippines, gongs have a central profusion or knot, hence the term bossed gongs. They are three of types: (1) sets of graduated gongs laid in a row called the kulintang ; (2) larger, deep-rimmed gongs with sides that are turned in called agung , and (3) gongs with narrower rims and less prominent bosses called gandingan . These gongs may be played alone but are often combined with other instruments to form various types of ensembles. -

Post-9/11 Brown and the Politics of Intercultural Improvisation A

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE “Sound Come-Unity”: Post-9/11 Brown and the Politics of Intercultural Improvisation A Dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Music by Dhirendra Mikhail Panikker September 2019 Dissertation Committee: Dr. Deborah Wong, Chairperson Dr. Robin D.G. Kelley Dr. René T.A. Lysloff Dr. Liz Przybylski Copyright by Dhirendra Mikhail Panikker 2019 The Dissertation of Dhirendra Mikhail Panikker is approved: Committee Chairperson University of California, Riverside Acknowledgments Writing can feel like a solitary pursuit. It is a form of intellectual labor that demands individual willpower and sheer mental grit. But like improvisation, it is also a fundamentally social act. Writing this dissertation has been a collaborative process emerging through countless interactions across musical, academic, and familial circles. This work exceeds my role as individual author. It is the creative product of many voices. First and foremost, I want to thank my advisor, Professor Deborah Wong. I can’t possibly express how much she has done for me. Deborah has helped deepen my critical and ethnographic chops through thoughtful guidance and collaborative study. She models the kind of engaged and political work we all should be doing as scholars. But it all of the unseen moments of selfless labor that defines her commitment as a mentor: countless letters of recommendations, conference paper coachings, last minute grant reminders. Deborah’s voice can be found across every page. I am indebted to the musicians without whom my dissertation would not be possible. Priya Gopal, Vijay Iyer, Amir ElSaffar, and Hafez Modirzadeh gave so much of their time and energy to this project. -

The Application of Bonang Gamelan Music Based on Mobile Application

International Journal of Recent Technology and Engineering (IJRTE) ISSN: 2277-3878, Volume-8 Issue-6, March 2020 The Application of Bonang Gamelan Music Based on Mobile Application Wan Hassan W A S., Rosli D.I., Ariffin A., Ahmad F., Jamin J learning which was practiced at local institutions of higher Abstract: The application of bonang gamelan music based on learning such as Malaysian Open University (OUM) (Zoraini, mobile application was developed with the aim of maintaining the 2010). This aspect will indirectly increase the productivity of tradition of traditional musical instruments in the society of this individual skills in daily life as well as foster continuous modern day. Users can recognise and learn how to play the traditional musical instruments, especially bonang gamelan by learning practices. Striking from the use of distance learning using mobile phone technology. This application provides and e-learning methods, the education world strives to convenience for users without spending time and money and they explore the dimensions of learning for users who want to learn can also access it anywhere. The development of this animated anytime and anywhere. Then, the term learning method is application is based on the ADDIE methodology and uses Adobe mobile or is called m-learning (Brown, 2005). This Flash software as a platform to develop this music app. The respondents involved in the development of this music app consist m-learning method is akin to self-learning using mobile of six (6) specialists in bonang gamelan music and IT devices such as mobile telephony, personal digital assistant professionals. The user respondents were ten (10) students of the (PDA), Palm Talk and others as learning tools (Wagner, Faculty of Technical and Vocational Education (FPTV). -

Korean March Defying Jnnta

"'v-'r—s V- '.- y'’- f >•'*,« V'‘V ; \- •. .. •■‘J' ■/ t C b s d a v , m a b c h m , 1 9 m A n n t. D dr Nri P i m m K m lilldftB'tW lLVB': The Weathet lEvpttfng F orth# Week Elided Foreeiaet ef H. 8. Wsothar nari— M a n iiU ,lM I Partial ’ cleaHiig and Mreeay to> chairman is Chester Andrew of Mid. give# them a sebss of Mystic Review Women’s Bene Hie Brtitlah American Club iVUl Ity and self estsem they need *t night with little drop la tempera fit Assn., will meet tonii^t at 8 have its aimiial meeting with elec 116 Ootemon Rd. Speaker Explains 1 3 ,9 6 6 About Town VSCG Band that age, ture. Lowest atronnd SO. Iw tty at Odd Fellows Hall. Guan& are tion of officers Saturday at 6 p.m. William L. Broodwell Is the softheAadlt cloudy, breesy and eoathraed eeoi at the cKibhouse. bandmaster. He has been with the Youth Prohlems ■ H ie Rev. James L. Ransom, New I Canter Churefa Mottien Ghib reminded to attend for guard I o f OirmUatioB lliursday^' HUgheet iUi to 40. work. band olnce 1946 and Its conductor pastor of the PrSebyterian Ohur^, M ancHe»ter-^A City of Village Charm ' i|40 xnaat tom om m nt 8 pjn. In The Rent. Clifford O. Simpson, To ploy f or since 1960. ’Hie band’s strength is Home environment,,1s extremely and Roger Cottle were hosts at the LOW Prie^st tita Mnderg^arten r o o m of the Disabled .^merican Veterans pastor of Center Congregational 47 men. -

East Java – Bali Power Distribution Strengthening Project

*OFFICIAL USE ONLY PT PLN (Persero) East Java – Bali Power Distribution Strengthening Project Environmental & Social Management Planning Framework (Version for Disclosure) January 2020 *OFFICIAL USE ONLY BASIC INFORMATION 1. Country and Project Name: Indonesia – East Java & Bali Power Distribution Strengthening Project 2. Project Development Objective: The expansion of the distribution network comprises erection of new poles, cable stringing, and installation of distribution transformers. 3. Expected Project Benefits: Construction of about 17,000 km distribution lines and installation of distribution transformers in East Java and Bali 4. Identified Project Environmental and Social Risks: Social Risks. It is envisaged that this project will require (i) use of no more than 0.2 m2 of land for installation of concrete poles and approximately 4m2 for installation of transformers (either in cabinet of between two concrete poles or on one pole); limited directional drilling (approx. 200-300m) to run cables under major roads and limited trenching (usually less than 500m) in urban environments, and (iii) possible removal of non-land assets (primarily trimming or felling of trees) for stringing of conductors. While restrictions on land use within the existing right of way apply, the land requirements for the distribution network (lines and transformers) are considered manageable with normal mitigation measures. Project activities will not (i) require land acquisition, (ii) cause physical or economic displacement; and/or (ii) result in adverse impacts to Indigenous Peoples groups and/or members of ethnic minorities. Environmental risks are principally induced by the establishment of the network across natural habitats and potential impact on fauna (in particular avifauna and terrestrial fauna susceptible to access the distribution lines or transformers such as monkeys or other tree dwelling scavenging animals that frequent semi urban environments), and the management of waste (e.g. -

Relationship with Percussion Instruments

Multimedia Figure X. Building a Relationship with Percussion Instruments Bill Matney, Kalani Das, & Michael Marcionetti Materials used with permission by Sarsen Publishing and Kalani Das, 2017 Building a relationship with percussion instruments Going somewhere new can be exciting; it might also be a little intimidating or cause some anxiety. If I go to a party where I don’t know anybody except the person who invited me, how do I get to know anyone else? My host will probably be gracious enough to introduce me to others at the party. I will get to know their name, where they are from, and what they commonly do for work and play. In turn, they will get to know the same about me. We may decide to continue our relationship by learning more about each other and doing things together. As music therapy students, we develop relationships with music instruments. We begin by learning instrument names, and by getting to know a little about the instrument. We continue our relationship by learning technique and by playing music with them! Through our experiences and growth, we will be able to help clients develop their own relationships with instruments and music, and therefore be able to 1 strengthen the therapeutic process. Building a relationship with percussion instruments Recognize the Know what the instrument is Know where the Learn about what the instrument by made out of (materials), and instrument instrument is or was common name. its shape. originated traditionally used for. We begin by learning instrument names, and by getting to know a little about the instrument. -

![HUMAN GAMELAN LESSON ONE ] May 26, 2011](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6837/human-gamelan-lesson-one-may-26-2011-1946837.webp)

HUMAN GAMELAN LESSON ONE ] May 26, 2011

[HUMAN GAMELAN LESSON ONE ] May 26, 2011 Lesson by: Vera H. Flaig B.Mus. B.Ed. Ph.D. Description: This lesson explores the concepts of Frequency (speed of a vibration commonly known as pitch) and Duration (length of vibration) through movement and sound. Curricular Outcomes: This lesson is best for older Primary and younger Junior students (grades 3-5). At the conclusion of this lesson, students will be able to understand the various layers that make up the texture of gamelan music. Given that these layers are based upon the duration and frequency of the vibration of each instrument, they will then be able to apply their knowledge to more complex problem solving related to the physics of sound production. Materials: large room with plenty of space for movement plus the following items: a frame-drum, a xylophone (with wooden bars) and a metalophone; a white board with different-colored dry-erase markers; and a CD or MP3 player. You will also need: the notation and a recording of “Bubaran Kembang Pacar,” and the Introduction to Javanese Gamelan power-point slides (in the resources folder), plus a projector. Getting Ready Write out the notation for “Bubaran Kembang Pacar” on the white board. Just write out the numbers for the balungan without any extra symbols for the structural parts; these will be added later. Set up the xylophone (the one with wooden bars) and the metalophone in the following manner: take off the E key, put the F key in its place and add an F# key. Put stickers on the instrument with number 1 being a B, 2 = C; 3 = D; 4 = F; 5 = F#; and 6 = G. -

Sunan Kali Jaga

Sunan Kali Jaga Sunan Kali Jaga is one of the Wali Sanga,1 and remains an important figure for Muslims in Java because of his work in spreading Islam and integrating its teachings into the Javanese tradition. Throughout his time proselytizing, he used art forms that, at the time, were both amenable to and treasured by the people of Java. Sunan Kali Jaga is thought to have been born in 1455, with the name Raden Syahid (Raden Sahid) or Raden Abdurrahman. He was the son of Aria Wilatikta, an official in Tuban,2 East Java, who was descended from Ranggalawe, an official of the Majapahit Kingdom during the time of Queen Tri Buwana Tungga Dewi and King Hayam Wuruk. Sunan Kali Jaga’s childhood coincided with the collapse of the Majapahit Kingdom recorded in the sengkalan “Sirna Ilang Kertaning Bhumi,”3 referring to the year 1400 Caka4 (1478). Seeing the desperate situation of the people of Majapahit, Raden Syahid decided to become a bandit who would rob the kingdom’s stores of crops and the rich people of Majapahit, and give his plunder to the poor. He became well known as Brandal5 Lokajaya. One day when Raden Syahid was in the forest, he accosted an old man with a cane, which he stole, thinking it was made from gold. He said that he would sell the cane and give the money to the poor. The old man was Sunan Bonang,6 and he did not approve of Raden Syahid’s actions. Sunan Bonang advised Raden Syahid that God would not accept such bad deeds; even though his intentions were good, his actions were wrong. -

Music 316: MUSIC CULTURES of the WORLD - ASIA

Music 316: MUSIC CULTURES OF THE WORLD - ASIA Prof. Ter Ellingson 28D Music 543-7211 [email protected] Class Website: http://faculty.washington.edu/ellingsn/Music_Cultures_of_the_World-Asia Su 2012.html CD 3: SOUTHEAST ASIA Laos 1. Khen "Nam phat khay", "In the Current of the Mekong", performed by Nouthong Phimvilayphone on khen, a free-reed bamboo mouth organ with varying numbers of pipes (16 in this example); melody accompanied by harmony and occasional counterpoint in 2-3 parts. (Laos 1 A: 1) Indonesia 2. Kecak (Bali) Ramayana epic performance by male chorus and soloists in gamelan svara or "vocal gamelan" style: some voices sing "trunk" melody and gong parts to punctuate rhythmic cycle, some sing solo parts of characters in story, while others Khen shout in interlocking rhythmic patterns. Kecak chorus of Teges village, Bali. (E/I Recording) 3. Legong (Bali) Music for dance by young girls depicting story of Prince Lasem and Princess Langkesari, played by Gamelan Legong orchestra consisting of metallophones (xylophones with metal keys instead of wood), flutes, and gong chimes (tuned sets of small kettle-shaped gongs with knobbed central bosses) playing "trunk" melody, faster elaborations, and slower extractions of it; larger gongs which punctuate key points in rhythmic cycle; and rhythmic elaborations by drums and cymbals. Performed by Gamelan orchestra of Teges village. (E/I Recording) Gamelan (Java) Music Cultures 316 - Asia CD 3 Prof. Ellingson 2 4. Udan Mas (Java) "Golden Rain", gamelan piece in Bubaran form (gongan cycle of sixteen beats with gong on beat 16; kenong on beats 4, 8, 12; kempul on 6, 10, 14; and kethuk on 1, 3, 5, 7, 9, 11, 13, 15). -

Through Music, FSU Professor Escapes to Brazil

4D » SUNDAY, JULY 30, 2017 » TALLAHASSEE DEMOCRAT Tallahassee Democrat - 07/30/2017 Copy Reduced to 60% from original to fit letter page Page : D04 TLH LOCAL Through music, FSU professor escapes to Brazil AMANDA SIERADZKI COUNCIL ON CULTURE & ARTS Music sits somewhere within the realms of escape and transcendence for Dr. Michael Bakan, a professor of ethnomusicology at Florida State University. When he sits to play, he feels himself go into a heightened state where the groove of the music moves his head in circles, lurching his body along with its rhythms, eyes closed, face turned upwards. “Sometimes I get teased about how funny I look, and I agree when I see it on video,” laughed Bakan, who’s become particularly transported by Brazilian music and artists. “It has this incredibly deep, rich rhythm and these lush harmonies that go on and on. Where western music revolves around three or four chords, Brazilian composers are able to make har- monic progressions that are ridiculously complex, but are put together in a way that touches you in a basic, emotional place.” Every Tuesday evening at The Blue Tavern, Bakan comes together with a cohort of musicians in the hopes of giving Tallahassee a similarly full experi- ence via their weekly performance: Roda Vibe! Roda, pronounced ‘hoda’ as per its Portuguese origins, translates to circle in the phrase “roda de choro.” Choro is the genre of Brazilian music, often heard in the bars, clubs, or late night venues in Rio de Janiero. As a drummer, Bakan plays a specific role, keeping the beat while letting the music unfold and the other musicians improvise around him. -

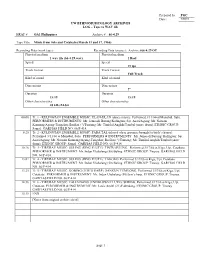

Tape to WAV File HRAF # OA1 Philippines Archive # 66-4

Prepared by PGC Date: 7/30/15 UW ETHNOMUSICOLOGY ARCHIVES LOG – Tape to WAV file HRAF # OA1 Philippines Archive # 66-4.29 Tape Title Music from Jolo and Cotabato (March 11 and 17, 1966) Recording Data (work tape): Recording Data (source): Archive #66-4.29 OT Physical medium Physical medium 1 wav file (66-4.29.wav) 1 Reel Speed Speed 15 ips Track Format Track Format Full Track Kind of sound Kind of sound Dimensions Dimensions 7” Duration Duration 15:19 15:19 Other characteristics Other characteristics 48 kHz/24-bit 00:00 Tr. 1 - KULINGTAN ENSEMBLE MUSIC: ULAN-ULAN (dance music). Performed 3/11/66 at Manubul, Sulu. PERFORMERS & INSTRUMENTS: Mr. Jamasali Burung/Kulingtan; Sqt. Asari/Agung; Mr. Nursam Kunnang/Agung-Tungalan; Basilan (?)/Tuntung; Mr. Timidul Angkih/Tambul (snare drum). ETHNIC GROUP: Samal. GARFIAS FIELD NO. 66/P-414. 8:25 Tr. 2 - KULINGTAN ENSEMBLE MUSIC: PABA TAL (played when groom is brought to bride’s house). Performed 3/11/66 at Manubul, Sulu. PERFORMERS & INSTRUMENTS: Mr. Jamasali Burung/ Kulingtan; Sqt. Asari/Agung; Mr. Nursam Kunnang/Agung-Tungalan; Basilan (?)/Tuntung; Mr. Timidul Angkih/Tambul (snare drum). ETHNIC GROUP: Samal. GARFIAS FIELD NO. 66/P-414. 10:26 Tr. 3 - TIRURAY MUSIC: SULING (RING FLUTE): TINTU SULING. Performed 3/17/66 at Kiga, Upi, Cotabato. PERFORMER & INSTRUMENT: Mr. Indun Ulubalang (50)/Suling. ETHNIC GROUP: Tiruray. GARFIAS FIELD NO. 66/P-414. 13:02 Tr. 4 - TIRURAY MUSIC: SULING (RING FLUTE): TAKOKO. Performed 3/17/66 at Kiga, Upi, Cotabato. PERFORMER & INSTRUMENT: Mr. Indun Ulubalang (50)/Suling. ETHNIC GROUP: Tiruray.