El Big Bang I L'univers Primitiu

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Infrared Spectroscopy of Nearby Radio Active Elliptical Galaxies

The Astrophysical Journal Supplement Series, 203:14 (11pp), 2012 November doi:10.1088/0067-0049/203/1/14 C 2012. The American Astronomical Society. All rights reserved. Printed in the U.S.A. INFRARED SPECTROSCOPY OF NEARBY RADIO ACTIVE ELLIPTICAL GALAXIES Jeremy Mould1,2,9, Tristan Reynolds3, Tony Readhead4, David Floyd5, Buell Jannuzi6, Garret Cotter7, Laura Ferrarese8, Keith Matthews4, David Atlee6, and Michael Brown5 1 Centre for Astrophysics and Supercomputing Swinburne University, Hawthorn, Vic 3122, Australia; [email protected] 2 ARC Centre of Excellence for All-sky Astrophysics (CAASTRO) 3 School of Physics, University of Melbourne, Melbourne, Vic 3100, Australia 4 Palomar Observatory, California Institute of Technology 249-17, Pasadena, CA 91125 5 School of Physics, Monash University, Clayton, Vic 3800, Australia 6 Steward Observatory, University of Arizona (formerly at NOAO), Tucson, AZ 85719 7 Department of Physics, University of Oxford, Denys, Oxford, Keble Road, OX13RH, UK 8 Herzberg Institute of Astrophysics Herzberg, Saanich Road, Victoria V8X4M6, Canada Received 2012 June 6; accepted 2012 September 26; published 2012 November 1 ABSTRACT In preparation for a study of their circumnuclear gas we have surveyed 60% of a complete sample of elliptical galaxies within 75 Mpc that are radio sources. Some 20% of our nuclear spectra have infrared emission lines, mostly Paschen lines, Brackett γ , and [Fe ii]. We consider the influence of radio power and black hole mass in relation to the spectra. Access to the spectra is provided here as a community resource. Key words: galaxies: elliptical and lenticular, cD – galaxies: nuclei – infrared: general – radio continuum: galaxies ∼ 1. INTRODUCTION 30% of the most massive galaxies are radio continuum sources (e.g., Fabbiano et al. -

The Herschel Sprint PHOTO ILLUSTRATION: PATRICIA GILLIS-COPPOLA, HERSCHEL IMAGE: WIKIMEDIA S&T

The Herschel Sprint PHOTO ILLUSTRATION: PATRICIA GILLIS-COPPOLA, HERSCHEL IMAGE: WIKIMEDIA S&T 34 April 2015 sky & telescope William Herschel’s Extraordinary Night of DiscoveryMark Bratton Recreating the legendary sweep of April 11, 1785 There’s little doubt that William Herschel was the most clearly with his instruments. As we will see, he did make signifi cant astronomer of the 18th century. His accom- occasional errors in interpretation, despite the superior plishments included the discovery of Uranus, infrared optics; for instance, he thought that the planetary nebula radiation, and four planetary satellites, as well as the M57 was a ring of stars. compilation of two extensive catalogues of double and The other factor contributing to Herschel’s interest multiple stars. His most lasting achievement, however, was the success of his sister, Caroline, in her study of the was his exhaustive search for undiscovered star clusters sky. He had built her a small telescope, encouraging her and nebulae, a key component in his quest to understand to search for double stars and comets. She located Messier what he called “the construction of the heavens.” In Her- objects and more, occasionally fi nding star clusters and schel’s time, astronomers were concerned principally with nebulae that had escaped the French astronomer’s eye. the study of solar system objects. The search for clusters Over the course of a year of observing, she discovered and nebulae was, up to that point, a haphazard aff air, with about a dozen star clusters and galaxies, occasionally not- a total of only 138 recorded by all the observers in history. -

A Search For" Dwarf" Seyfert Nuclei. VII. a Catalog of Central Stellar

TO APPEAR IN The Astrophysical Journal Supplement Series. Preprint typeset using LATEX style emulateapj v. 26/01/00 A SEARCH FOR “DWARF” SEYFERT NUCLEI. VII. A CATALOG OF CENTRAL STELLAR VELOCITY DISPERSIONS OF NEARBY GALAXIES LUIS C. HO The Observatories of the Carnegie Institution of Washington, 813 Santa Barbara St., Pasadena, CA 91101 JENNY E. GREENE1 Department of Astrophysical Sciences, Princeton University, Princeton, NJ ALEXEI V. FILIPPENKO Department of Astronomy, University of California, Berkeley, CA 94720-3411 AND WALLACE L. W. SARGENT Palomar Observatory, California Institute of Technology, MS 105-24, Pasadena, CA 91125 To appear in The Astrophysical Journal Supplement Series. ABSTRACT We present new central stellar velocity dispersion measurements for 428 galaxies in the Palomar spectroscopic survey of bright, northern galaxies. Of these, 142 have no previously published measurements, most being rela- −1 tively late-type systems with low velocity dispersions (∼<100kms ). We provide updates to a number of literature dispersions with large uncertainties. Our measurements are based on a direct pixel-fitting technique that can ac- commodate composite stellar populations by calculating an optimal linear combination of input stellar templates. The original Palomar survey data were taken under conditions that are not ideally suited for deriving stellar veloc- ity dispersions for galaxies with a wide range of Hubble types. We describe an effective strategy to circumvent this complication and demonstrate that we can still obtain reliable velocity dispersions for this sample of well-studied nearby galaxies. Subject headings: galaxies: active — galaxies: kinematics and dynamics — galaxies: nuclei — galaxies: Seyfert — galaxies: starburst — surveys 1. INTRODUCTION tors, apertures, observing strategies, and analysis techniques. -

DGSAT: Dwarf Galaxy Survey with Amateur Telescopes

Astronomy & Astrophysics manuscript no. arxiv30539 c ESO 2017 March 21, 2017 DGSAT: Dwarf Galaxy Survey with Amateur Telescopes II. A catalogue of isolated nearby edge-on disk galaxies and the discovery of new low surface brightness systems C. Henkel1;2, B. Javanmardi3, D. Mart´ınez-Delgado4, P. Kroupa5;6, and K. Teuwen7 1 Max-Planck-Institut f¨urRadioastronomie, Auf dem H¨ugel69, 53121 Bonn, Germany 2 Astronomy Department, Faculty of Science, King Abdulaziz University, P.O. Box 80203, Jeddah 21589, Saudi Arabia 3 Argelander Institut f¨urAstronomie, Universit¨atBonn, Auf dem H¨ugel71, 53121 Bonn, Germany 4 Astronomisches Rechen-Institut, Zentrum f¨urAstronomie, Universit¨atHeidelberg, M¨onchhofstr. 12{14, 69120 Heidelberg, Germany 5 Helmholtz Institut f¨ur Strahlen- und Kernphysik (HISKP), Universit¨at Bonn, Nussallee 14{16, D-53121 Bonn, Germany 6 Charles University, Faculty of Mathematics and Physics, Astronomical Institute, V Holeˇsoviˇck´ach 2, CZ-18000 Praha 8, Czech Republic 7 Remote Observatories Southern Alps, Verclause, France Received date ; accepted date ABSTRACT The connection between the bulge mass or bulge luminosity in disk galaxies and the number, spatial and phase space distribution of associated dwarf galaxies is a dis- criminator between cosmological simulations related to galaxy formation in cold dark matter and generalised gravity models. Here, a nearby sample of isolated Milky Way- class edge-on galaxies is introduced, to facilitate observational campaigns to detect the associated families of dwarf galaxies at low surface brightness. Three galaxy pairs with at least one of the targets being edge-on are also introduced. Approximately 60% of the arXiv:1703.05356v2 [astro-ph.GA] 19 Mar 2017 catalogued isolated galaxies contain bulges of different size, while the remaining objects appear to be bulgeless. -

Making a Sky Atlas

Appendix A Making a Sky Atlas Although a number of very advanced sky atlases are now available in print, none is likely to be ideal for any given task. Published atlases will probably have too few or too many guide stars, too few or too many deep-sky objects plotted in them, wrong- size charts, etc. I found that with MegaStar I could design and make, specifically for my survey, a “just right” personalized atlas. My atlas consists of 108 charts, each about twenty square degrees in size, with guide stars down to magnitude 8.9. I used only the northernmost 78 charts, since I observed the sky only down to –35°. On the charts I plotted only the objects I wanted to observe. In addition I made enlargements of small, overcrowded areas (“quad charts”) as well as separate large-scale charts for the Virgo Galaxy Cluster, the latter with guide stars down to magnitude 11.4. I put the charts in plastic sheet protectors in a three-ring binder, taking them out and plac- ing them on my telescope mount’s clipboard as needed. To find an object I would use the 35 mm finder (except in the Virgo Cluster, where I used the 60 mm as the finder) to point the ensemble of telescopes at the indicated spot among the guide stars. If the object was not seen in the 35 mm, as it usually was not, I would then look in the larger telescopes. If the object was not immediately visible even in the primary telescope – a not uncommon occur- rence due to inexact initial pointing – I would then scan around for it. -

Ngc Catalogue Ngc Catalogue

NGC CATALOGUE NGC CATALOGUE 1 NGC CATALOGUE Object # Common Name Type Constellation Magnitude RA Dec NGC 1 - Galaxy Pegasus 12.9 00:07:16 27:42:32 NGC 2 - Galaxy Pegasus 14.2 00:07:17 27:40:43 NGC 3 - Galaxy Pisces 13.3 00:07:17 08:18:05 NGC 4 - Galaxy Pisces 15.8 00:07:24 08:22:26 NGC 5 - Galaxy Andromeda 13.3 00:07:49 35:21:46 NGC 6 NGC 20 Galaxy Andromeda 13.1 00:09:33 33:18:32 NGC 7 - Galaxy Sculptor 13.9 00:08:21 -29:54:59 NGC 8 - Double Star Pegasus - 00:08:45 23:50:19 NGC 9 - Galaxy Pegasus 13.5 00:08:54 23:49:04 NGC 10 - Galaxy Sculptor 12.5 00:08:34 -33:51:28 NGC 11 - Galaxy Andromeda 13.7 00:08:42 37:26:53 NGC 12 - Galaxy Pisces 13.1 00:08:45 04:36:44 NGC 13 - Galaxy Andromeda 13.2 00:08:48 33:25:59 NGC 14 - Galaxy Pegasus 12.1 00:08:46 15:48:57 NGC 15 - Galaxy Pegasus 13.8 00:09:02 21:37:30 NGC 16 - Galaxy Pegasus 12.0 00:09:04 27:43:48 NGC 17 NGC 34 Galaxy Cetus 14.4 00:11:07 -12:06:28 NGC 18 - Double Star Pegasus - 00:09:23 27:43:56 NGC 19 - Galaxy Andromeda 13.3 00:10:41 32:58:58 NGC 20 See NGC 6 Galaxy Andromeda 13.1 00:09:33 33:18:32 NGC 21 NGC 29 Galaxy Andromeda 12.7 00:10:47 33:21:07 NGC 22 - Galaxy Pegasus 13.6 00:09:48 27:49:58 NGC 23 - Galaxy Pegasus 12.0 00:09:53 25:55:26 NGC 24 - Galaxy Sculptor 11.6 00:09:56 -24:57:52 NGC 25 - Galaxy Phoenix 13.0 00:09:59 -57:01:13 NGC 26 - Galaxy Pegasus 12.9 00:10:26 25:49:56 NGC 27 - Galaxy Andromeda 13.5 00:10:33 28:59:49 NGC 28 - Galaxy Phoenix 13.8 00:10:25 -56:59:20 NGC 29 See NGC 21 Galaxy Andromeda 12.7 00:10:47 33:21:07 NGC 30 - Double Star Pegasus - 00:10:51 21:58:39 -

Towards a Library of Synthetic Galaxy Spectra and Preliminary Results of Classification and Parametrization of Unresolved Galaxies for Gaia

A&A 504, 1071–1084 (2009) Astronomy DOI: 10.1051/0004-6361/200912014 & c ESO 2009 Astrophysics Towards a library of synthetic galaxy spectra and preliminary results of classification and parametrization of unresolved galaxies for Gaia. II P. Tsalmantza1,2, M. Kontizas2, B. Rocca-Volmerange3,4 ,C.A.L.Bailer-Jones1, E. Kontizas5, I. Bellas-Velidis5, E. Livanou2, R. Korakitis6, A. Dapergolas5, A. Vallenari7, and M. Fioc3,8 1 Max-Planck-Institut für Astronomie, Königstuhl 17, 69117 Heidelberg, Germany e-mail: [email protected] 2 Department of Astrophysics Astronomy & Mechanics, Faculty of Physics, University of Athens, 15783 Athens, Greece 3 Institut d’Astrophysique de Paris, 98bis Bd Arago, 75014 Paris, France 4 Université de Paris-Sud XI, IAS, 91405 Orsay Cedex, France 5 IAA, National Observatory of Athens, PO Box 20048, 118 10 Athens, Greece 6 Dionysos Satellite Observatory, National Technical University of Athens, 15780 Athens, Greece 7 INAF, Padova Observatory, Vicolo dell’Osservatorio 5, 35122 Padova, Italy 8 Université Pierre et Marie Curie, 4 place Jussieu, 75005 Paris, France Received 9 March 2009 / Accepted 8 June 2009 ABSTRACT Aims. This paper is the second in a series, implementing a classification system for Gaia observations of unresolved galaxies. Our goals are to determine spectral classes and estimate intrinsic astrophysical parameters via synthetic templates. Here we describe (1) a new extended library of synthetic galaxy spectra; (2) its comparison with various observations; and (3) first results of classification and parametrization experiments using simulated Gaia spectrophotometry of this library. Methods. Using the PÉGASE.2 code, based on galaxy evolution models that take account of metallicity evolution, extinction correc- tion, and emission lines (with stellar spectra based on the BaSeL library), we improved our first library and extended it to cover the domain of most of the SDSS catalogue. -

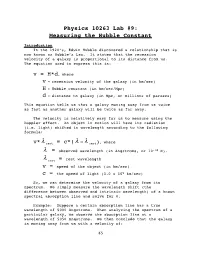

P10263v1.2 Lab 9 Text

Physics 10263 Lab #9: Measuring the Hubble Constant Introduction In the 1920’s, Edwin Hubble discovered a relationship that is now known as Hubble’s Law. It states that the recession velocity of a galaxy is proportional to its distance from us. The equation used to express this is: v = H*d, where v = recession velocity of the galaxy (in km/sec) H = Hubble constant (in km/sec/Mpc) d = distance to galaxy (in Mpc, or millions of parsecs) This equation tells us that a galaxy moving away from us twice as fast as another galaxy will be twice as far away. The velocity is relatively easy for us to measure using the Doppler effect. An object in motion will have its radiation (i.e. light) shifted in wavelength according to the following formula: v* λ rest = c*( λ - λ rest), where λ = observed wavelength (in Angstroms, or 10-10 m). λ rest = rest wavelength v = speed of the object (in km/sec) c = the speed of light (3.0 x 105 km/sec) So, we can determine the velocity of a galaxy from its spectrum. We simply measure the wavelength shift (the difference between observed and intrinsic wavelength) of a known spectral absorption line and solve for v. Example: Suppose a certain absorption line has a true wavelength of 5000 Angstroms. When analyzing the spectrum of a particular galaxy, we observe the absorption line at a wavelength of 5050 Angstroms. We then conclude that the galaxy is moving away from us with a velocity of: !65 (5050-5000) v = [ /5000] * 300,000 = 3000 km/sec In order to estimate the distances to galaxies, we’re going to use a distance determination technique known as the “standard ruler”. -

The SAGA Survey. II. Building a Statistical Sample of Satellite Systems Around Milky Way-Like Galaxies

The SAGA Survey. II. Building a Statistical Sample of Satellite Systems around Milky Way-like Galaxies Item Type Article; text Authors Mao, Y.-Y.; Geha, M.; Wechsler, R.H.; Weiner, B.; Tollerud, E.J.; Nadler, E.O.; Kallivayalil, N. Citation Mao, Y. Y., Geha, M., Wechsler, R. H., Weiner, B., Tollerud, E. J., Nadler, E. O., & Kallivayalil, N. (2021). The SAGA Survey. II. Building a Statistical Sample of Satellite Systems around Milky Way–like Galaxies. The Astrophysical Journal, 907(2), 85 DOI 10.3847/1538-4357/abce58 Publisher IOP Publishing Ltd Journal Astrophysical Journal Rights Copyright © 2021 The American Astronomical Society. All rights reserved. Download date 07/10/2021 10:20:37 Item License http://rightsstatements.org/vocab/InC/1.0/ Version Final published version Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/660488 The Astrophysical Journal, 907:85 (35pp), 2021 February 1 https://doi.org/10.3847/1538-4357/abce58 © 2021. The American Astronomical Society. All rights reserved. The SAGA Survey. II. Building a Statistical Sample of Satellite Systems around Milky Way–like Galaxies Yao-Yuan Mao1,8 , Marla Geha2 , Risa H. Wechsler3,4 , Benjamin Weiner5 , Erik J. Tollerud6 , Ethan O. Nadler3 , and Nitya Kallivayalil7 1 Department of Physics and Astronomy, Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey, Piscataway, NJ 08854, USA 2 Department of Astronomy, Yale University, New Haven, CT 06520, USA 3 Kavli Institute for Particle Astrophysics and Cosmology and Department of Physics, Stanford University, Stanford, CA 94305, USA 4 SLAC National Accelerator -

On the Observational Diagnostics to Separate Classical and Disk-Like Bulges

MNRAS 000,1–15 (2018) Preprint 3 July 2018 Compiled using MNRAS LATEX style file v3.0 On the observational diagnostics to separate classical and disk-like bulges Luca Costantin,1? E. M. Corsini,1;2 J. Méndez-Abreu,3;4 L. Morelli,1;2;5 E. Dalla Bontà,1;2 and A. Pizzella1;2 1Dipartimento di Fisica e Astronomia ‘G. Galilei’, Università di Padova, vicolo dell’Osservatorio 3, I-35122 Padova, Italy 2INAF - Osservatorio Astronomico di Padova, vicolo dell’Osservatorio 5, I-35122 Padova, Italy 3Instituto de Astrofísica de Canarias, Calle Vía Láctea s/n, E-38200 La Laguna, Tenerife, Spain 4Departamento de Astrofísica, Universidad de La Laguna, Calle Astrofísico Francisco Sánchez s/n, E-38205 La Laguna, Tenerife, Spain 5Instituto de Astronomía y Ciencias Planetarias, Universidad de Atacama, Copiapó, Chile Accepted version on 2018 June 27 ABSTRACT Flattened bulges with disk-like properties are considered to be the end product of secular evolution processes at work in the inner regions of galaxies. On the contrary, classical bulges are characterized by rounder shapes and thought to be similar to low- luminosity elliptical galaxies. We aim at testing the variety of observational diagnos- tics which are commonly adopted to separate classical from disk-like bulges in nearby galaxies. We select a sample of eight unbarred lenticular galaxies to be morphologi- cally and kinematically undisturbed with no evidence of other components than bulge and disk. We analyze archival data of broad-band imaging from SDSS and integral- field spectroscopy from the ATLAS3D survey to derive the photometric and kinematic properties, line-strength indices, and intrinsic shape of the sample bulges. -

Inner Rings in Disc Galaxies: Dead Or Alive�,

A&A 555, L4 (2013) Astronomy DOI: 10.1051/0004-6361/201321983 & c ESO 2013 Astrophysics Letter to the Editor Inner rings in disc galaxies: dead or alive, S. Comerón1,2 1 University of Oulu, Astronomy Division, Department of Physics, PO Box 3000, 90014 Oulu, Finland e-mail: [email protected] 2 Finnish Centre of Astronomy with ESO (FINCA), University of Turku, Väisäläntie 20, 21500 Piikkiö, Finland Received 28 May 2013 / Accepted 17 June 2013 ABSTRACT In this Letter, I distinguish “passive” inner rings as those with no current star formation as distinct from “active” inner rings that have undergone recent star formation. I built a sample of nearby galaxies with inner rings observed in the near- and mid-infrared from the NIRS0S and the S4G surveys. I used archival far-ultraviolet (FUV) and Hα imaging of 319 galaxies to diagnose whether their inner rings are passive or active. I found that passive rings are found only in early-type disc galaxies (−3 ≤ T ≤ 2). In this range of stages, 21 ± 3% and 28 ± 5% of the rings are passive according to the FUV and Hα indicators, respectively. A ring that is passive according to the FUV is always passive according to Hα, but the reverse is not always true. Ring-lenses form 30–40% of passive rings, which is four times more than the fraction of ring-lenses found in active rings in the stage range −3 ≤ T ≤ 2. This is consistent with both a resonance and a manifold origin for the rings because both models predict purely stellar rings to be wider than their star-forming counterparts. -

Marketing Fragment 8.5 X 12.T65

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-85893-9 - Steve O’Meara’s Herschel 400 Observing Guide Steve O’Meara Index More information Index Ancient City Astronomy Club (ACAC), ix , Aquila NGC 5195 (H I-186), 194 4 , 5 specific objects in NGC 5273 (H I-98), 193 asterisms NGC 6755 (H VII-19), 248 Canis Major Coathanger, 252 NGC 6756 (H VII-62), 249 specific objects in Kemble’s Cascade, 35 , 36 NGC 6781 (H III-743), 249 NGC 2204 (H VII-13), 48 M73, 267 Aries NGC 2354 (H VII-16), 48 Astronomical League (AL), ix specific objects in NGC 2360 (H VII-12), 49 Herschel 400 certificates, ix NGC 772 (H I-112), 309 NGC 2362 (H VII-17), 49 Auriga Cassiopeia Barbuy, B., 240 specific objects in specific objects in Bayer, Johann NGC 1644 (H VIII-59), 22 NGC 129 (H VIII-79), 292 and Greek letters for stars, 10 NGC 1857 (H VII-33), 24 NGC 136 (H VI-35), 292 Bernoulli, J., 141 , 181 , 216 NGC 1907 (H VII-39), 24 NGC 185 (H II-707), 287 Bica, E., 240 NGC 1931 (H I-261), 25 NGC 225 (H VIII-78), 293 Blinking Planetary Nebula (see NGC 2126 (H VIII-68), 22 NGC 278 (H I-159), 288 NGC 6826) NGC 2281 (H VIII-71), 25 NGC 381 (H VIII-64), 293 Box Galaxy (see NGC 4449) Bootes NGC 436 (H VII-45), 295 bright nebulae specific objects in NGC 457 (H VII-42), 295 definition of, 5 NGC 5248 (H I-34), 197 NGC 559 (H VII-48), 296 specific objects NGC 5466 (H VI-9), 212 NGC 637 (H VII-49), 296 M8, 241 NGC 5557 (H I-99), 212 NGC 654 (H VII-46), 298 M27, 252 NGC 5676 (H I-189), 209 NGC 659 (H VIII-65), 297 NGC 1788 (H V-32), 30 NGC 5689 (H I-188), 209 NGC 663 (H VI-31), 298 NGC 1931