Indianapolis Women's Oral History Project

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Flooding the Border: Development, Politics, and Environmental Controversy in the Canadian-U.S

FLOODING THE BORDER: DEVELOPMENT, POLITICS, AND ENVIRONMENTAL CONTROVERSY IN THE CANADIAN-U.S. SKAGIT VALLEY by Philip Van Huizen A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in The Faculty of Graduate Studies (History) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Vancouver) June 2013 © Philip Van Huizen, 2013 Abstract This dissertation is a case study of the 1926 to 1984 High Ross Dam Controversy, one of the longest cross-border disputes between Canada and the United States. The controversy can be divided into two parts. The first, which lasted until the early 1960s, revolved around Seattle’s attempts to build the High Ross Dam and flood nearly twenty kilometres into British Columbia’s Skagit River Valley. British Columbia favoured Seattle’s plan but competing priorities repeatedly delayed the province’s agreement. The city was forced to build a lower, 540-foot version of the Ross Dam instead, to the immense frustration of Seattle officials. British Columbia eventually agreed to let Seattle raise the Ross Dam by 122.5 feet in 1967. Following the agreement, however, activists from Vancouver and Seattle, joined later by the Upper Skagit, Sauk-Suiattle, and Swinomish Tribal Communities in Washington, organized a massive environmental protest against the plan, causing a second phase of controversy that lasted into the 1980s. Canadian and U.S. diplomats and politicians finally resolved the dispute with the 1984 Skagit River Treaty. British Columbia agreed to sell Seattle power produced in other areas of the province, which, ironically, required raising a different dam on the Pend d’Oreille River in exchange for not raising the Ross Dam. -

'08 Primary Forgery Brings Probe

V17, N8 Sunday, Oct. 9, 2011 ‘08 primary forgery brings probe Fake signatures on Clinton, Obama petitions in St. Joe By RYAN NEES Howey Politics Indiana ERIN BLASKO and KEVIN ALLEN South Bend Tribune SOUTH BEND — The signatures of dozens, if not hundreds, of northern Indiana residents were faked on petitions used to place presidential candidates on the state pri- mary ballot in 2008, The Tribune and Howey Politics Indiana have revealed in an investigation. Several pag- es from petitions used to qualify Hillary Clinton and Barack Obama Then U.S. Sen. Hillary Clinton signs an autograph while touring Allison Transmis- for the state’s sion in Speedway. She almost didn’t qualify for the Indiana ballot for the 2008 pri- Democratic mary, which she won by less than 1 percent over Barack Obama. President Obama primary contain is shown here at Concord HS in Elkhart. (HPI Photos by Brian A. Howey and Ryan names and signa- Nees) tures that appear to have been candidate Jim Schellinger. The petitions were filed with the copied by hand from a petition for Democratic gubernatorial Continued on page 3 Romney by default? By CHRIS SAUTTER WASHINGTON - Barack Obama has often been described as lucky on his path to the presidency. But Mitt Romney is giving new meaning to the term “political luck,” as one Re- “A campaign is too shackley for publican heavyweight after another someone like me who’s a has decided against joining the current field of GOP candidates for maverick, you know, I do go president. Yet, the constant clamor rogue and I call it like I see it.” for a dream GOP candidate has ex- - Half-term Gov. -

Politics Indiana

Politics Indiana V15 N15 Thursday, Nov. 13, 2008 The Obama ‘landslide’ impact entire GOP ticket like a car bomb that created the environ- Bulen Symposium weighs the ment for Bulen, Bill Ruckleshaus, Larry Borst, Noble Pearcy, shifts in demographics, media Beurt SerVaas and others to form the Republican Action Committee the next year in preparation for seizing control By BRIAN A. HOWEY of the Marion County party. It became the footing for the INDIANAPOLIS - In late 1998 I asked L. Keith Indiana Republican machine from 1966 to 1988 that would Bulen what he thought dominate the state. about President Clinton Out of the RAC would and he responded, come names that still “Best candidate I’ve reverberate today: ever thought, heard or Danny Burton, John dreamed of.” Mutz, Richard Lugar, As you read Charlie Bosma, Rex the data and impres- Early and eventually, sions emanating last Mitch Daniels. Monday from the As our analysis re- Bulen Symposium on vealed last week, Dan- American Politics as iels and Obama domi- well as some of our nated 2008 in what own, ponder what the may be seen as one of legendary Republican the transformational operative might have elections in Indiana thought about Barack history. What we don’t Obama. The last time a Democrat carried Indiana was 1964 know is whether this and it was that LBJ blowout of Barry Goldwater that hit the signals a new, broad swing state era, See Page 3 As GM goes .... By BRIAN A. HOWEY CARMEL - The lease on my Ford F-150 is just about up, so I’ve been doing my research. -

Politics: Reports

, VOL. IX, No. 19 OCTOBER 15, 1973 FORUM 25 CENTS ship. Senate Majority Leader Ray John POLITICS: REPORTS son may run for the State Supreme Court next spring, but if he loses that battle, he may contest Steinhilber for the special convention "will provide the nomination to succeed Warren. • WISCONSIN another occasion for Republicans to get together and hate one another." Despite the party's admitteJ internal COLORADO MAD ISO N - With both a problems, a number of possible can senatorial and gubernatorial election didates have already surfaced for next DENVER - Colorado Gov. John coming up in 1974, the Wisconsin Re year's nominations - many of them Vanderhoof (R) looks like a man publican Party is in difficult straits. from the State Senate. caught between a rock and a hard If a $500,000 debt wasn't adequate With former Defense Secretary Mel place . as he resists calling a special affiiction, the GOP also faces two for vin Laird out of the gubernatorial pic session of the Colorado Legislature to midable opponents in Sen. Gaylord ture in Washington, Attorney General deal with the Denver's annexation Nelson (D) and Gov: Patrick Lucey. Robert W. Warren is the leading can powers. (See the September 1973 Nelson won re-election in 1968 against didate for governor. However, Warren FORUM.) If Vanderhoof calls the Jerris Leonard, later a top Justice De is also interested in a federal judge session, he loses the support of Denver partment official, with 62 percent of ship (assuming the post does not go Republicans; if he does not, he loses the vote. -

INDIANA's 1988 GUBERNATORIAL RESIDENCY CHALLENGE Joseph

INDIANA’S 1988 GUBERNATORIAL RESIDENCY CHALLENGE Joseph Hadden Hogsett Submitted to the faculty of the University Graduate School in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts in the Department of History Indiana University June 2007 Accepted by the Faculty, Indiana University, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts. Robert G. Barrows, Ph.D., Chair Elizabeth Brand Monroe, Ph.D. Master’s Thesis Committee William A. Blomquist, Ph.D. ii Dedicated to the memory of my colleague and friend, Jon D. Krahulik iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I take this opportunity to thank the people who helped make this paper possible. Dr. Robert G. Barrows served as my seminar professor, my mentor and the Chair of this thesis committee. Many other graduate students have acknowledged his sound advice, his guidance, his editing and his sense of humor. All of those also apply here. In my case, however, above all, I owe him a debt of gratitude for patience. This paper began as a concept in his seminar in the spring of 2002, but was not finished for five years. Even if Dr. Barrows had known then how flawed and distracted the author would prove to be, I am convinced he still would have agreed to chair the project. His patience is a gift. I also acknowledge the advice offered unconditionally by the committee’s other members, Dr. Elizabeth Brand Monroe and Dr. William A. Blomquist. Though they, like Dr. Barrows, possessed sufficient probable cause to notify authorities of a “missing person”, both exercised incredible restraint and, in so doing, no doubt violated some antiquainted canon of academic protocol. -

AVONDALE THEATER AUGUST 30—SEPTEMBER 4 'Look for the Authentic Label

- AVONDALE THEATER AUGUST 30—SEPTEMBER 4 'look for the authentic label STOLES • JACKETS • COATS $1500 to $8500 "Terms as Desired" HERBERT FRED DAVIDSON DAVIDSON glendale center 62nd & keys/one /&6 RAY HENDRICKS announces a change of name and expansion of... AMMOND ORGAN STUDIOS o HOW RENAMED music INC. THE HOME OF HAMMOND NOW ALSO OFFERING A LARGE SELECTION OF PIANOS BUILT BY LEADING PIANO COMPANIES 34th AND MERIDIAN SOUTHERN PLAZA Why settle for less when there's DELLEN Indiana's largest Oldsmobile dealer— with over 500 new cars to choose from! 'turnrunt CORNER 52nd & KEYSTONE Your Rocket Service Center Open Daily 7 A.M. to 6 P.M., Thursday till 9 P.M. Closed Saturday & Sunday IN THE MEADOWS LUNCHEON AND DINNERS DANCE TO, BE ENTERTAINED NIGHTLY BY THE The SHADES 3900 N. RURAL • PHONE 547-6526 1930 E. 46th Street 111 I AO ' - ' 100% Humon Hair A Wig is a ^U I IK V . , . Specialists in Wig Styling Must for Carefree WW lUv ' • • Men's Hairpieces Summer Fun I' instante beaute MARCIA ANDREWS, Manager » 251-3606 AVONDALE in-the-meadows THEATER One of the Nation's Foremost Summer Stock Theaters Now in its Thirteenth Season presents TOM MARVIN HELEN MALA DRAKE MILLER O'CONNELL POWERS IN "AFFAIRS OF STATE" by Louis Verneuil with GEORGE WILLEFORD PAUL LENNON Directed By TOM ADKINS Produced by LEWIS A. BREINER Scenic Design Lighting Design LINDA BREWER HERMAN TEEPE, Jr. Play Produced by Special Arrangement of Samuel French, Inc. PROFESSIONAL CAR WASH Stoc&o GAS N' WASH Look at Your Car . Everyone Else Does 1219 N. -

Dr. Otis R. Bowen Papers SPEC.042

Dr. Otis R. Bowen papers SPEC.042 This finding aid was produced using the Archivists' Toolkit February 16, 2015 Describing Archives: A Content Standard Ball State University Archives and Special Collections Alexander M. Bracken Library 2000 W. University Avenue Muncie, Indiana, 47306 765-285-5078 [email protected] Dr. Otis R. Bowen papers SPEC.042 Table of Contents Summary Information ................................................................................................................................. 4 Biographical Note.......................................................................................................................................... 5 Scope and Contents....................................................................................................................................... 6 Arrangement...................................................................................................................................................6 Administrative Information .........................................................................................................................9 Controlled Access Headings........................................................................................................................10 Collection Inventory.................................................................................................................................... 11 Series 1: Indiana University Medical School Papers, 1907-1967.........................................................11 -

Sagamore of the Wabash Award Was Created During the Term of Governor Ralph Gates, Who Served from 1945 to 1949

Sagamore of the Wabash by Jeffrey Graf Reference Services Department Herman B Wells Library Indiana University Libraries - Bloomington The French Republic rewards merit most notably with grades of membership in the Legion of Honor, originally created by Napoleon for worthies of his empire. In Britain the sovereign can choose from a range of honors to acknowledge service or accomplishment. Although the Most Noble Order of the Garter is reserved for the happy few, a simple knighthood might be an appropriate reward. Within the royal gift, too, is recognition in the form of a life peerage or even av hereditary title. On the other side of the Atlantic the American president has available the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the United States’ highest civilian honor. In case a potential honoree does not quite measure up to that distinction, there is a second-highest civilian honor, the Presidential Citizen’s Medal. Not to be outdone by the executive branch, the Congress created the Congressional Gold Medal, its highest award. Like nations, professional societies, institutes, universities, associations, businesses, museums, clubs, fraternal groups, and other organizations pay tribute to the meritorious. Such entities, devoted to all kinds of endeavor from the fine arts to professional sports, present scrolls, plaques, medals, trophies, certificates, keys to the city and other tokens of esteem to their laureates. County fairs award blue ribbons; the Kennel Club chooses Best in Show. Athletes compete for the gold and silver and bronze or the Stanley and Davis and Ryder cups. For mathematicians there is the Fields Medal; in the same intellectual realm, there are the Nobel Prizes. -

R Ichard Lugar

Editor’s Note: Here’s how a “Leader of the Year” article normally works: The writer tells the story of the honoree, focusing on why the person is being recognized. Included is a sampling of quotes from others describing the winner’s impact. Without diminishing the accomplishments of any honorees, past or present, the 2013 Government Leader of the Year (who also earned the Chamber’s inaugural honor in 1990) is no typical award winner. Richard Lugar’s story and accomplishments are so well-known that he is one of the recipients of this year’s Presidential Medal of Freedom. The nation’s highest civilian honor is presented to those who have made especially meritorious contributions to the security or national interests of the United States. He is being honored at the White House this month. Richard Lugar accepts the 1990 Government Leader of the Year award State, national and global leaders have outlined Lugar’s contributions from Chamber chairman Lee Cross. throughout his nearly 50 years of public service. But a 50-minute interview with Lugar is too priceless not to share as many of his comments as possible. Enjoy the Richard Lugar story – in his own words. BizVoice®: What sparked your interest in politics? Richard Lugar: “It began with my dad letting me (then eight years old) sit up with him until 3 a.m. as Wendell Willkie was nominated in 1940 as the Republican candidate for president. This led me to be intensely interested in political conventions long before they appeared on television. Subsequently, I began to think conceivably that I might be walking across the stage at one of them and that happened in Miami Beach (in 1972) when I was a keynote speaker at the Republican National Convention. -

President Nixon's Favorite Mayor: Richard G. Lugar's Mayoral Years

President Nixon’s Favorite Mayor: Richard G. Lugar’s Mayoral Years and Rise to National Politics By Kelsey Green University of Indianapolis Undergraduate History Program, Spring 2021 Undergraduate Status: Senior [email protected] Green 1 A WARM HOOSIER WELCOME On February 5th, 1970 at 12:20 in the afternoon, President Richard Milhous Nixon landed in Indianapolis, Indiana. Nixon was accompanied in Air Force One by First Lady Pat Nixon, Secretary Donald Rumsfeld, Secretary George W. Romney, and his top aides H. R. Haldeman and John Ehrlichman among others. His other advisor, Daniel P. Moynihan, would rendezvous with the presidential entourage later that day.i Awaiting his arrival on the tarmac, Governor Edgar Whitcomb and Mayor Richard Lugar led the local reception committee. Donning winter overcoats, the president and Mayor Lugar are seen cordially greeting one another in a striking black and white photo. On the left, the young Lugar extends his hand to a much older and harried Nixon. Both men are smiling and framed by a large camera and microphone to record this historic moment.ii Nixon would later remark that he was received with a “warm Hoosier welcome on a rather cold day.”iii This was the first time Nixon had visited Indianapolis as president and was his first publicized meeting with Mayor Lugar, the up-and-coming politician who now represented the revitalized Republican Party in Indianapolis. After exchanging pleasantries and traveling to Indianapolis City Hall, Nixon and Lugar spoke to the crowd of approximately 1,000 Hoosiers before -

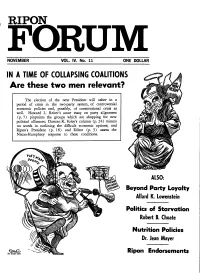

Are These Two Men Relevant?

RIPON NOVEMBER VOL. IV. No. 11 ONE DOLLAR IN A TIME OF COLLAPSING COALITIONS Are these two men relevant? The election of the next President will usher in a period of crisis in the two-party system, of controversial economic policies and, possibly, of constitutional crisis as well. Howard 1. Reiter's acute essay on party alignment (p.7) pinpoints the groups which are shopping for new political alliances; Duncan K. Foley's column (p. 24) minces no words in outlining the difficult economic options; and Ripon's President (p. 16) and Editor (p. 3) assess the Nixon-Humphrey response to these conditions. ALSO: Beyond Party Loyalty Allard K. Lowenstein Politics of Starvation Robert B. Choate Nutrition Policies Dr. Jean Mayer Ripon Endorsements SUMMARY OF CONTENTS EDITORIALS STATE BY STATE These include Ripon's 19GB list of endorsements in ~ixon sho~d take Indiana, but the race getting at state-wide and Congressional races. -S tention there lS the contest between Democratic incum bent Birch Bayh and the GOP golden boy William D. MUTINY IN THE RANKS Ruckleshaus. -17 Walter Meany and his cohorts have a dream - inher Ohio may find itself with a liberal Republican sena- iting control of the collapsing Democratic Party - and tor. -17 they are pulling out all the stops for their man Hubert Every vote will count in Oregon, particularly in the Humphrey. But politically rebellious workers and a ban Bob Packwood-Wayne Morse bruiser. -18 tam-sized oversight are torpedoing these grand designs, Texas could have its first Republican governor since says Wnuam J. -

Preserving Doc's Image Extent

Otis R. Bowen, William Du Bois Jr.. Doc: Memories from a Life in Public Service. Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 2000. x + 232 $24.95, cloth, ISBN 978-0-253-33767-2. Reviewed by John M. Glen Published on H-Indiana (February, 2001) Preserving Doc's Image extent. Yet it sheds little light on Indiana's history Otis R. Bowen ranks among the most power‐ during a time when Bowen wielded considerable ful and admired politicians in modern Indiana influence over the state's public affairs. history. The power was gained through winning Indeed, what is most striking about this ac‐ twenty of twenty-one primary and general elec‐ count of a life in public service is its general lack tions between 1952 and 1976. During that period of thoroughness about that career. Instead, Bowen won election to the Indiana House of Rep‐ Bowen devotes an extensive amount of space to resentatives in 1956 and worked there for four‐ his personal history. At least one-third of the en‐ teen years, capped by a six-year reign as speaker tire book is consumed by it; widowed twice, of that chamber. He became governor in 1972 and Bowen's longest chapter extols the three women was subsequently the frst in that office to serve who have been married to him. In these passages consecutive four-year terms since the adoption of Bowen provides a cliched, anecdotal account of the state's 1851 constitution. He concluded his his poor-but-proud upbringing, when family public career as President Ronald Reagan's Secre‐ members and schoolteachers taught him to work tary of Health and Human Services between 1985 hard and be honest, thrifty, and persistent.