Emergent Nationalism in European Maps of the Eighteenth Century

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Longitude of the Mediterranean Throughout History: Facts, Myths and Surprises Luis Robles Macías

The longitude of the Mediterranean throughout history: facts, myths and surprises Luis Robles Macías To cite this version: Luis Robles Macías. The longitude of the Mediterranean throughout history: facts, myths and sur- prises. E-Perimetron, National Centre for Maps and Cartographic Heritage, 2014, 9 (1), pp.1-29. hal-01528114 HAL Id: hal-01528114 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01528114 Submitted on 27 May 2017 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. e-Perimetron, Vol. 9, No. 1, 2014 [1-29] www.e-perimetron.org | ISSN 1790-3769 Luis A. Robles Macías* The longitude of the Mediterranean throughout history: facts, myths and surprises Keywords: History of longitude; cartographic errors; comparative studies of maps; tables of geographical coordinates; old maps of the Mediterranean Summary: Our survey of pre-1750 cartographic works reveals a rich and complex evolution of the longitude of the Mediterranean (LongMed). While confirming several previously docu- mented trends − e.g. the adoption of erroneous Ptolemaic longitudes by 15th and 16th-century European cartographers, or the striking accuracy of Arabic-language tables of coordinates−, we have observed accurate LongMed values largely unnoticed by historians in 16th-century maps and noted that widely diverging LongMed values coexisted up to 1750, sometimes even within the works of one same author. -

Apocryphal Voyages to the Northwest Coast of America by Henry R

1931.] Apocryphal Voyages to Coast of America 179 APOCRYPHAL VOYAGES TO THE NORTHWEST COAST OF AMERICA BY HENRY R. WAGNER FOREWORD The opportunity afforded me to publish the present article, whieh might appropriately be called More Imaginary California Geography, allows me to make a few corrections and amplifica- tions to Some Imaginary California Geography, published in the PROCEEDINGS for April, 1926. On page 21 of that article in referring to Juan de Fuca a statement is made about the abortive expedition of 1589 or 1590 financed by Hernando de Sanctotis in which Fuca perhaps took part. There was an expedition of about 1589 or 1590 financed by Sanctotis but it was not the abortive one to which Fuca refers. This took place in late 1593 or early 1594 and was financed by Sebastian Vizcaino's company. On page 48 the date of Father Benavides' memorial is incorrectly given as 1632 instead of 1630. Since 1926 a map of Guilleaume Bleau has been unearthed which is believed by Dr. F. A. Wieder to have been made in 1648. A reproduction of it was published in Vol. 3 of the Monumenta Cartographica. If the date assigned to the map by Dr. Wieder is correct it is probably the earliest one of Briggs' type with corrections. I have lately received from Mr. G. R. G. Conway in Mexico City a photograph of a manuscript map in Tomo X of the Muñoz documents in the Real Academia de la Historia, Madrid. It is not dated nor is the Derrotero which it precedes. The place names on the northwest coast are different from those on the Briggs map and the arrangement of them is also different. -

Recent Publications 1984 — 2017 Issues 1 — 100

RECENT PUBLICATIONS 1984 — 2017 ISSUES 1 — 100 Recent Publications is a compendium of books and articles on cartography and cartographic subjects that is included in almost every issue of The Portolan. It was compiled by the dedi- cated work of Eric Wolf from 1984-2007 and Joel Kovarsky from 2007-2017. The worldwide cartographic community thanks them greatly. Recent Publications is a resource for anyone interested in the subject matter. Given the dates of original publication, some of the materi- als cited may or may not be currently available. The information provided in this document starts with Portolan issue number 100 and pro- gresses to issue number 1 (in backwards order of publication, i.e. most recent first). To search for a name or a topic or a specific issue, type Ctrl-F for a Windows based device (Command-F for an Apple based device) which will open a small window. Then type in your search query. For a specific issue, type in the symbol # before the number, and for issues 1— 9, insert a zero before the digit. For a specific year, instead of typing in that year, type in a Portolan issue in that year (a more efficient approach). The next page provides a listing of the Portolan issues and their dates of publication. PORTOLAN ISSUE NUMBERS AND PUBLICATIONS DATES Issue # Publication Date Issue # Publication Date 100 Winter 2017 050 Spring 2001 099 Fall 2017 049 Winter 2000-2001 098 Spring 2017 048 Fall 2000 097 Winter 2016 047 Srping 2000 096 Fall 2016 046 Winter 1999-2000 095 Spring 2016 045 Fall 1999 094 Winter 2015 044 Spring -

The Travels of Anacharsis the Younger in Greece

e-Perimetron , Vol. 3, No. 3, 2008 [101-119] www.e-perimetron.org | ISSN 1790-3769 George Tolias * Antiquarianism, Patriotism and Empire. Transfer of the cartography of the Travels of Anacharsis the Younger , 1788-1811 Keywords : Late Enlightenment; Antiquarian cartography of Greece; Abbé Barthélemy; Anacharsis; Barbié du Bocage ; Guillaume Delisle; Rigas Velestinlis Charta. Summary The aim of this paper is to present an instance of cultural transfer within the field of late Enlightenment antiquarian cartography of Greece, examining a series of maps printed in French and Greek, in Paris and Vienna, between 1788 and 1811 and related to Abbé Barthé- lemy’s Travels of Anacharsis the Younger in Greece . The case-study allows analysing the al- terations of the content of the work and the changes of its symbolic functions, alterations due first to the transferral of medium (from a textual description to a cartographic representation) and next, to the successive transfers of the work in diverse cultural environments. The trans- fer process makes it possible to investigate some aspects of the interplay of classical studies, antiquarian erudition and politics as a form of interaction between the French and the Greek culture of the period. ‘The eye of History’ The Travels of Anacharsis the Younger in Greece , by Abbé Jean-Jacques Barthélemy (1716- 1795) 1, was published on the eve of the French Revolution (1788) and had a manifest effect on its public. “In those days”, the Perpetual Secretary of the Académie des Inscriptions et Belles Lettres, Bon-Joseph Dacier (1742-1833) was to recall in 1826, “an unexpected sight came to impress and surprise our spirit. -

ٌ³إكïلُأغ³ف ف»ٌد³غ³َلَُامف»ٌاَ »فھ ². λ

Ապագա Հանդես (75) 1 Apaga Periodical(75) Armenia in the ancient geographical sources Ed. Baghdasarian Relatively a lot of findings were discovered during excavations in Babylonia and other countries of Mesopotamia, where clay tiles or tablets served as a material for writing, and acquired incomparable durability after backing. The oldest finds, dating back to 2400-2200 BC, with a schematic picture of Mesopotamia represent the river, flowing along the valley, between two mountain countries; before emptying into the sea, the river forms a delta, the situation of the countries is indicated by means of circles. Among engineering maps saved, there is a piece plate with plan Nippura city in Mesopotamia, which represents the walls and gates of the city, the most important buildings, canals and other facilities. There are also isolated images, reproducing speculative presentation of ancient people about structure and boundaries of the world. Among them there is a Babylonian tablet of 6th century BC, accompanied by the text. It depicts the Earth as a flat circle, washed by Ocean, named “Bitter River”. Mountains, which descend to the river Euphrates, are situated in the north. Gulf (Persian) extends deep into the land. Babylon is placed in the center of the Earth. Assyria is represented to the north-east of Babylon, in the north adjoining with the country Urartu (Armenia). In addition to Babylon several other cities are also indicated on the map by oval mark. Behind the Ocean lie seven islands, symbolizing the unknown world. The concept of the world in the form of disk, surrounded by ocean, with the public or religious center of the country, was widespread and even appeared on maps of the early Middle Ages1. -

The Portal to Texas History: Building a Partnership Model for a Statewide Digital Library

The Portal to Texas History: Building a Partnership Model for a Statewide Digital Library Dreanna Belden University of North Texas, USA Mark Phillips University of North Texas, USA Tara Carlisle University of Oklahoma, USA Cathy Nelson Hartman University of North Texas, USA ABSTRACT The Portal to Texas History serves as a gateway to Texas history materials. The Portal consists of collections hosted by the University of North Texas (UNT) Libraries in partnership and collaboration with over 280 Texas libraries, museums, archives, historical societies, genealogical societies, state agencies, corporations, and private family collections. With a continuously growing collection of over half a million digital resources, The Portal to Texas History stands as an example of a highly successful collaborative digital library which relies heavily on partnerships in order to function at the high level. The proposed book chapter will describe all aspects of establishing the collaborations to create the Portal including the background of the project, marketing the initiative to potential partners, partnership roles and agreements, preservation of all digital master files, technical infrastructure to support partnership models, promoting standards and good practice, funding issues and development, research studies to understand partner benefits and user groups, sustainability issues, and future research directions. Keywords: Digital, Libraries, Collaborative, Partner, History, Collections, Online, Access, Materials, Project, UNT INTRODUCTION The Portal to Texas HistorySM serves as a gateway to Texas history materials in which users are able to discover anything from an ancestor's picture to a rare historical map. The Portal consists of collections hosted by the University of North Texas (UNT) Libraries in partnership and collaboration with over 280 Texas libraries, museums, archives, historical societies, genealogical societies, state agencies, corporations, and private family collections. -

Study-2L.Pdf

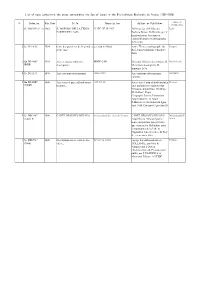

List of maps containing the areas surrounding the Sea of Japan in the Bibliotheque Nationale de France(1551-1600) Place of No Index.no Pub.Year Title Description Author or Publisher Publication 1 Ge DD 5105 (1-3) 1561 IL DISEGNO DELLA TERZA MARE DE MANGI All'il mo sigr il Sr Marcho Italy PARTE DELL'ASIA Fucharo Barone Di Kirchberg c' d' maifsen horen: Giacomo di caftaldi Piamatese Cofmographo in Venetia 2 Ge D 11830 1584 Carte des provinces de la grande et Le Sein de Manji Andre Thevet, cosmographe du France petite Asie Roy, Chez Guillaume Chardiere, Paris 3 Ge DD 2987 1595 Asia ex magna orbis terre MARE CJN Mercator (G) terre descriptione G. Netherlands (6456) descriptione... Mercatoris desumpta G.M. Iunionris 1595 4 Ge D 11833 1598 Asia. partium orbis maxima Mare Chin Asia. partium orbis maxima, Germany coloniae 5 Ge DD 2987 1600 Asia vetus et quae ad hodiernam ANUS ORI Asia vetus et quæ ad hodiernamLo France (10045) locorum... corŭ positionem respondet Aut N.Sanson Abbavillæo. Chriftian. Mi Galliarʔ Regis Geographa.Lutetiæ Paryiorium Apud Autorem Et Apud P.Mariette via Iacobæa fub figno Spei 1650. Cum privilegio Ann 20 6 Ge DD 2987 1600 CARTE DES ISLES DU IAPO. ocean oriental / Mer de Coreer CARTE DES ISLES DU IAPO. Netherlands/F (7445) B Esquelles est remarqvé par la rance route tant par mer que par terre, que tiennent les Hollandois pour se transporter de la Ville de Nagasaki a Iedo demeurre du Roy de ces mesmes isles. 7 Ge DD 2987 1600 Description exacte et fidele des la mer de coree voyage des ambassadeurs de France (7446) villes,.. -

Adriaan Reland Mapping Persia and Japan, 1705–1715

chapter 8 ‘Geleerdster der Landbeschryveren’? Adriaan Reland Mapping Persia and Japan, 1705–1715 Tobias Winnerling In 1764 the Amsterdam learned journal Maandelyke uittreksels, of Boekzaal der geleerde waerelt called Adriaan Reland ‘den geleerdsten der Landbeschryveren’, ‘the most learned of land-describers’.1 Reland had won such praise with his short treatise on the location of the earthly paradise.2 Yet contemporaries might have been tempted to extend this judgement to another strand of his geographical-historical studies too, to cartography proper. For cartography was indeed one of the many facets of Reland’s scholarly pursuits. He published standalone maps as well as geographically informed works which relied on maps as a central part of their argument. His last major work, the two-volume Palaestina ex monumentis veteribus illustrata of 1714,3 constantly mapped the features of ancient Palestine discussed in the text to thematic maps dispersed throughout the book. Of all of Reland’s works this would be the one best suited to the heading of ‘land-description’, as it clearly illustrates his method of com- bining maps with further research on the topic on the one hand and of relying on contemporary indigenous sources in drafting these maps on the other. In the case of the Holy Land these were Biblical sources as well as ancient authors writing on Palestine, above all Flavius Josephus. Reland had projected an edi- tion of this work but was not able to carry it out before his death. The question I am going to ask in this chapter is whether this twofold approach to cartogra- phy can also be found in Reland’s standalone maps. -

The Roots of Nationalism

HERITAGE AND MEMORY STUDIES 1 HERITAGE AND MEMORY STUDIES Did nations and nation states exist in the early modern period? In the Jensen (ed.) field of nationalism studies, this question has created a rift between the so-called ‘modernists’, who regard the nation as a quintessentially modern political phenomenon, and the ‘traditionalists’, who believe that nations already began to take shape before the advent of modernity. While the modernist paradigm has been dominant, it has been challenged in recent years by a growing number of case studies that situate the origins of nationalism and nationhood in earlier times. Furthermore, scholars from various disciplines, including anthropology, political history and literary studies, have tried to move beyond this historiographical dichotomy by introducing new approaches. The Roots of Nationalism: National Identity Formation in Early Modern Europe, 1600-1815 challenges current international scholarly views on the formation of national identities, by offering a wide range of contributions which deal with early modern national identity formation from various European perspectives – especially in its cultural manifestations. The Roots of Nationalism Lotte Jensen is Associate Professor of Dutch Literary History at Radboud University, Nijmegen. She has published widely on Dutch historical literature, cultural history and national identity. Edited by Lotte Jensen The Roots of Nationalism National Identity Formation in Early Modern Europe, 1600-1815 ISBN: 978-94-6298-107-2 AUP.nl 9 7 8 9 4 6 2 9 8 1 0 7 2 The Roots of Nationalism Heritage and Memory Studies This ground-breaking series examines the dynamics of heritage and memory from a transnational, interdisciplinary and integrated approaches. -

A Study on the East Sea (Donghae) in the Werstern Old Map

A Study on the East Sea (Donghae) in the Werstern Old Map Lee Sang-tae (Office Directer, National Institute of Korean History) Mountains, rivers, and seas did not have any names in the ancient times. However, with the development of culture, people began to name these areas. The names of each mountain, river, and sea reflect a cultural heritage as well as the values of the people who lived around them. It is noted that due to the fact that Korea was a peninsula, surrounded with three sides water, the people of Korea were interested in the sea, and they named the coastal waters based on directions such as east, west, south, north and center. They called the seas the East Sea (Donghae in Korean), the West Sea (Seohae in Korean), and the South Sea (Namhae in Korean). The name "East Sea" first appeared during the reign of King Dongmyeong in the "History of the Koguryo Kingdom" in the History of the Three Kingdoms. The three Kingdoms - Silla, Koguryo, and Baekje - were established in BC 57, 37, and 18 respectively, while the East Sea was recognized since BC 59 before the establishment of the three Kingdoms. The East Sea has a long history in Korea. The name of the East Sea was changed into the Japan Sea, because of Japanese rule in Korea. Japan alterated it into the Japan Sea. To show this historical fact, I have analyzed the Western old maps. Regarding these maps, the Univ. of Southern California holds 146, the National Library of France 127, History Museum of Seoul 82, and individuals 52 respectively. -

Russian Cartography to Ca. 1700 L

62 • Russian Cartography to ca. 1700 L. A. Goldenberg the Sources of the Cartography of Russia,” Imago Mundi 16 (1962): The perception of a “foreign beginning” to Russian car- 33– 48. 1 tography is deeply rooted. It has been fostered by the 2. In al-Idrı¯sı¯’s large world map, Eastern Europe is placed on eight irretrievable loss of indigenous Russian maps of pre- sheets (nos. 54 –57, 64 –67), which show the Caspian lands, Bashkiria, seventeenth-century date, along with the unfamiliarity Volga Bulgaria, the upper reaches of the Severny (Severskiy) Donets, the with other sources. Thus the traditional cartographic im- Black Sea area, the lower Dniester area, the upper Dnieper area, the Carpathians, the Danube area, and the Baltic area, whereas the north- age of Russia was that provided by the Western European ern Caucasus and the lower Volga area are more distorted. In al-Idrı¯sı¯’s mapmakers. The name “Russia” first appeared in this map, sources for the ancient centers of ninth-century Rus are combined foreign cartographic record in the twelfth century. For ex- with more precise data on the well-traveled trade routes of the twelfth ample, on the Henry of Mainz mappamundi (ca. 1110), century. For al-Idrı¯sı¯ and the map of 1154, see S. Maqbul Ahmad, “Car- it is placed north of the mouth of the Danube; on the map tography of al-Sharı¯f al-Idı¯sı¯,” in HC 2.1:156 –74; Konrad Miller, Map- 2 pae arabicae: Arabische Welt- und Länderkarten des 9.–13. Jahrhun- of the cartographer al-Idrı¯sı¯ (1154), interesting geo- derts, 6 vols. -

Of 6 SPANISH MAPPING of TEXAS. Early in 1520 the Pilots Who Had

Page 1 of 6 SPANISH MAPPING OF TEXAS. Early in 1520 the pilots who had sailed the previous year with Alonso Álvarez de Pinedaqv laid before the Spanish crown an outline sketch of the Gulf of Mexico.qv This crude rendering, which survives in the Archivo General de Indias in Seville, represents the beginning of the Spanish mapping of Texas. A true cartographic landmark, it was the first European map portrayal of the Gulf based on actual exploration, as well as the first to show any part of what is now the state of Texas—hypothetical concepts of the Gulf of Mexico before its actual discovery notwithstanding. The Álvarez de Pineda sketch gave representation to the Mississippi River (called Río del Espíritu Santo) and to the Río Pánuco, which enters the Gulf at the site of present-day Tampico, dividing the Mexican states of Tamaulipas and Vera Cruz. While showing several river mouths along the Texas coast, it names none of them. Yet, before there was another known voyage to the northern Gulf, mapsqv began appearing with names attached to the Texas features, descriptive of what Álvarez de Pineda's crew had observed, or imagined. Virtually the only record of what the explorers reported after the voyage is a summary contained in a royal patent granting Francisco de Garayqv (governor of Jamaica and Álvarez de Pineda's patron) authority to settle the area of the discovery, which was named Amichel.qv The patent relates that the voyagers had seen gold-bearing rivers and natives wearing gold ornaments on their noses and earlobes; some were giants almost eight feet tall, others like pygmies.