Estimation of Turbulence Kinetic Energy Dissipation Rate in a Bora Event

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Estimation of the Dissipation Rate of Turbulent Kinetic Energy: a Review

Chemical Engineering Science 229 (2021) 116133 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Chemical Engineering Science journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/ces Review Estimation of the dissipation rate of turbulent kinetic energy: A review ⇑ Guichao Wang a, , Fan Yang a,KeWua, Yongfeng Ma b, Cheng Peng c, Tianshu Liu d, ⇑ Lian-Ping Wang b,c, a SUSTech Academy for Advanced Interdisciplinary Studies, Southern University of Science and Technology, Shenzhen 518055, PR China b Guangdong Provincial Key Laboratory of Turbulence Research and Applications, Center for Complex Flows and Soft Matter Research and Department of Mechanics and Aerospace Engineering, Southern University of Science and Technology, Shenzhen 518055, Guangdong, China c Department of Mechanical Engineering, 126 Spencer Laboratory, University of Delaware, Newark, DE 19716-3140, USA d Department of Mechanical and Aeronautical Engineering, Western Michigan University, Kalamazoo, MI 49008, USA highlights Estimate of turbulent dissipation rate is reviewed. Experimental works are summarized in highlight of spatial/temporal resolution. Data processing methods are compared. Future directions in estimating turbulent dissipation rate are discussed. article info abstract Article history: A comprehensive literature review on the estimation of the dissipation rate of turbulent kinetic energy is Received 8 July 2020 presented to assess the current state of knowledge available in this area. Experimental techniques (hot Received in revised form 27 August 2020 wires, LDV, PIV and PTV) reported on the measurements of turbulent dissipation rate have been critically Accepted 8 September 2020 analyzed with respect to the velocity processing methods. Traditional hot wires and LDV are both a point- Available online 12 September 2020 based measurement technique with high temporal resolution and Taylor’s frozen hypothesis is generally required to transfer temporal velocity fluctuations into spatial velocity fluctuations in turbulent flows. -

Turbulence Kinetic Energy Budgets and Dissipation Rates in Disturbed Stable Boundary Layers

4.9 TURBULENCE KINETIC ENERGY BUDGETS AND DISSIPATION RATES IN DISTURBED STABLE BOUNDARY LAYERS Julie K. Lundquist*1, Mark Piper2, and Branko Kosovi1 1Atmospheric Science Division Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, Livermore, CA, 94550 2Program in Atmospheric and Oceanic Science, University of Colorado at Boulder 1. INTRODUCTION situated in gently rolling farmland in eastern Kansas, with a homogeneous fetch to the An important parameter in the numerical northwest. The ASTER facility, operated by the simulation of atmospheric boundary layers is the National Center for Atmospheric Research (NCAR) dissipation length scale, lε. It is especially Atmospheric Technology Division, was deployed to important in weakly to moderately stable collect turbulence data. The ASTER sonic conditions, in which a tenuous balance between anemometers were used to compute turbulence shear production of turbulence, buoyant statistics for the three velocity components and destruction of turbulence, and turbulent dissipation used to estimate dissipation rate. is maintained. In large-scale models, the A dry Arctic cold front passed the dissipation rate is often parameterized using a MICROFRONTS site at approximately 0237 UTC diagnostic equation based on the production of (2037 LST) 20 March 1995, two hours after local turbulent kinetic energy (TKE) and an estimate of sunset at 1839 LST. Time series spanning the the dissipation length scale. Proper period 0000-0600 UTC are shown in Figure 1.The parameterization of the dissipation length scale 6-hr time period was chosen because it allows from experimental data requires accurate time for the front to completely pass the estimation of the rate of dissipation of TKE from instrumented tower, with time on either side to experimental data. -

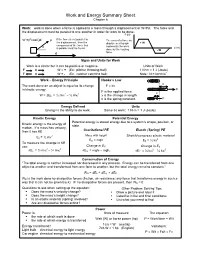

Work and Energy Summary Sheet Chapter 6

Work and Energy Summary Sheet Chapter 6 Work: work is done when a force is applied to a mass through a displacement or W=Fd. The force and the displacement must be parallel to one another in order for work to be done. F (N) W =(Fcosθ)d F If the force is not parallel to The area of a force vs. the displacement, then the displacement graph + W component of the force that represents the work θ d (m) is parallel must be found. done by the varying - W d force. Signs and Units for Work Work is a scalar but it can be positive or negative. Units of Work F d W = + (Ex: pitcher throwing ball) 1 N•m = 1 J (Joule) F d W = - (Ex. catcher catching ball) Note: N = kg m/s2 • Work – Energy Principle Hooke’s Law x The work done on an object is equal to its change F = kx in kinetic energy. F F is the applied force. 2 2 x W = ΔEk = ½ mvf – ½ mvi x is the change in length. k is the spring constant. F Energy Defined Units Energy is the ability to do work. Same as work: 1 N•m = 1 J (Joule) Kinetic Energy Potential Energy Potential energy is stored energy due to a system’s shape, position, or Kinetic energy is the energy of state. motion. If a mass has velocity, Gravitational PE Elastic (Spring) PE then it has KE 2 Mass with height Stretch/compress elastic material Ek = ½ mv 2 EG = mgh EE = ½ kx To measure the change in KE Change in E use: G Change in ES 2 2 2 2 ΔEk = ½ mvf – ½ mvi ΔEG = mghf – mghi ΔEE = ½ kxf – ½ kxi Conservation of Energy “The total energy is neither increased nor decreased in any process. -

Middle School Physical Science: Kinetic Energy and Potential Energy

MIDDLE SCHOOL PHYSICAL SCIENCE: KINETIC ENERGY AND POTENTIAL ENERGY Standards Bundle Standards are listed within the bundle. Bundles are created with potential instructional use in mind, based upon potential for related phenomena that can be used throughout a unit. MS-PS3-1 Construct and interpret graphical displays of data to describe the relationships of kinetic energy to the mass of an object and to the speed of an object. [Clarification Statement: Emphasis is on descriptive relationships between kinetic energy and mass separately from kinetic energy and speed. Examples could include riding a bicycle at different speeds, rolling different sizes of rocks downhill, and getting hit by a wiffle ball versus a tennis ball.] MS-PS3-2 Develop a model to describe that when the arrangement of objects interacting at a distance changes, different amounts of potential energy are stored in the system. [Clarification Statement: Emphasis is on relative amounts of potential energy, not on calculations of potential energy. Examples of objects within systems interacting at varying distances could include: the Earth and either a roller coaster cart at varying positions on a hill or objects at varying heights on shelves, changing the direction/orientation of a magnet, and a balloon with static electrical charge being brought closer to a classmate’s hair. Examples of models could include representations, diagrams, pictures, and written descriptions of systems.] [Assessment Boundary: Assessment is limited to two objects and electric, magnetic, and gravitational interactions.] MS-PS3-5. Engage in argument from evidence to support the claim that when the kinetic energy of an object changes, energy is transferred to or from the object. -

Chapter 7 Electricity Lesson 2 What Are Static and Current Electricity?

Chapter 7 Electricity Lesson 2 What Are Static and Current Electricity? Static Electricity • Most objects have no charge= the atoms are neutral. • They have equal numbers of protons and electrons. • When objects rub against another, electrons move from the atoms of one to atoms of the other object. • The numbers of protons and electrons in the atoms are no longer equal: they are either positively or negatively charged. • The buildup of charges on an object is called static electricity. • Opposite charges attract each other. • Charged objects can also attract neutral objects. • When items of clothing rub together in a dryer, they can pick up a static charge. • Because some items are positive and some are negative, they stick together. • When objects with opposite charges get close, electrons sometimes jump from the negative object to the positive object. • This evens out the charges, and the objects become neutral. • The shocks you can feel are called static discharge. • The crackling noises you hear are the sounds of the sparks. • Lightning is also a static discharge. • Where does the charge come from? • Scientists HYPOTHESIZE that collisions between water droplets in a cloud cause the drops to become charged. • Negative charges collect at the bottom of the cloud. • Positive charges collect at the top of the cloud. • When electrons jump from one cloud to another, or from a cloud to the ground, you see lightning. • The lightning heats the air, causing it to expand. • As cooler air rushes in to fill the empty space, you hear thunder. • Earth can absorb lightning’s powerful stream of electrons without being damaged. -

3. Energy, Heat, and Work

3. Energy, Heat, and Work 3.1. Energy 3.2. Potential and Kinetic Energy 3.3. Internal Energy 3.4. Relatively Effects 3.5. Heat 3.6. Work 3.7. Notation and Sign Convention In these Lecture Notes we examine the basis of thermodynamics – fundamental definitions and equations for energy, heat, and work. 3-1. Energy. Two of man's earliest observations was that: 1)useful work could be accomplished by exerting a force through a distance and that the product of force and distance was proportional to the expended effort, and 2)heat could be ‘felt’ in when close or in contact with a warm body. There were many explanations for this second observation including that of invisible particles traveling through space1. It was not until the early beginnings of modern science and molecular theory that scientists discovered a true physical understanding of ‘heat flow’. It was later that a few notable individuals, including James Prescott Joule, discovered through experiment that work and heat were the same phenomenon and that this phenomenon was energy: Energy is the capacity, either latent or apparent, to exert a force through a distance. The presence of energy is indicated by the macroscopic characteristics of the physical or chemical structure of matter such as its pressure, density, or temperature - properties of matter. The concept of hot versus cold arose in the distant past as a consequence of man's sense of touch or feel. Observations show that, when a hot and a cold substance are placed together, the hot substance gets colder as the cold substance gets hotter. -

Work, Power, & Energy

WORK, POWER, & ENERGY In physics, work is done when a force acting on an object causes it to move a distance. There are several good examples of work which can be observed everyday - a person pushing a grocery cart down the aisle of a grocery store, a student lifting a backpack full of books, a baseball player throwing a ball. In each case a force is exerted on an object that caused it to move a distance. Work (Joules) = force (N) x distance (m) or W = f d The metric unit of work is one Newton-meter ( 1 N-m ). This combination of units is given the name JOULE in honor of James Prescott Joule (1818-1889), who performed the first direct measurement of the mechanical equivalent of heat energy. The unit of heat energy, CALORIE, is equivalent to 4.18 joules, or 1 calorie = 4.18 joules Work has nothing to do with the amount of time that this force acts to cause movement. Sometimes, the work is done very quickly and other times the work is done rather slowly. The quantity which has to do with the rate at which a certain amount of work is done is known as the power. The metric unit of power is the WATT. As is implied by the equation for power, a unit of power is equivalent to a unit of work divided by a unit of time. Thus, a watt is equivalent to a joule/second. For historical reasons, the horsepower is occasionally used to describe the power delivered by a machine. -

Chapter 07: Kinetic Energy and Work Conservation of Energy Is One of Nature’S Fundamental Laws That Is Not Violated

Chapter 07: Kinetic Energy and Work Conservation of Energy is one of Nature’s fundamental laws that is not violated. Energy can take on different forms in a given system. This chapter we will discuss work and kinetic energy. If we put energy into the system by doing work, this additional energy has to go somewhere. That is, the kinetic energy increases or as in next chapter, the potential energy increases. The opposite is also true when we take energy out of a system. the grand total of all forms of energy in a given system is (and was, and will be) a constant. Exam 2 Review • Chapters 7, 8, 9, 10. • A majority of the Exam (~75%) will be on Chapters 7 and 8 (problems, quizzes, and concepts) • Chapter 9 lectures and problems • Chapter 10 lecture Different forms of energy Kinetic Energy: Potential Energy: linear motion gravitational rotational motion spring compression/tension electrostatic/magnetostatic chemical, nuclear, etc.... Mechanical Energy is the sum of Kinetic energy + Potential energy. (reversible process) Friction will convert mechanical energy to heat. Basically, this (conversion of mechanical energy to heat energy) is a non-reversible process. Chapter 07: Kinetic Energy and Work Kinetic Energy is the energy associated with the motion of an object. m: mass and v: speed SI unit of energy: 1 joule = 1 J = 1 kg.m2/s2 Work Work is energy transferred to or from an object by means of a force acting on the object. Formal definition: *Special* case: Work done by a constant force: W = ( F cos θ) d = F d cos θ Component of F in direction of d Work done on an object moving with constant velocity? constant velocity => acceleration = 0 => force = 0 => work = 0 Consider 1-D motion. -

Kinetic Energy Energy in Motion

ENERGY AND NASCAR LESSON PLAN 2: KINETIC ENERGY ENERGY IN MOTION TIME REQUIRED: 1 hour MATERIALS: String, heavy and light objects (such as a pencil and a pack of index cards), paper cup, masking tape, ruler, textbooks, cardboard, toy car or completed car from the Three Ds of Speed ACTIVITY SHEETS: Kinetic Energy Activity Sheet Central question: consider the height of a racetrack’s What is kinetic energy? banking when considering how cars will THINK perform. Remind students that three factors affect how much gravitational potential energy the racecar has at the Have students consider what happens top of a racetrack’s banking: the height to potential energy when it’s released of the banking, the car’s mass, and the from its stored state. Explain that energy force of gravity. Given the fact that mass can’t be created or destroyed, but it impacts kinetic energy, all racecars does change from one form to another. must weigh 3,300 pounds (without Potential energy is often converted into a driver). Having identical masses another type of energy called kinetic makes sure the cars are competitively energy. Kinetic energy is the energy equal. NASCAR enforces these rules of motion. Kinetic energy can also by inspecting each car before and after transform back into potential energy. each race. (If you have not ex plored For example, you’d use kinetic energy aerodynamics with your class, refer to to lift a ball to the top of a ramp. That moved after the swinging object the Three Ds of Speed unit to learn how energy would be stored in the ball as struck it. -

Kinetic Energy and the Work-Energy Principle

Class 15 Quiz on Wednesday. Sec 202 will meet in Pasteur 301, around the corner from the Tutoring center in Southwick Wed. Clicker Question. Kinetic Energy and the Work-Energy Principle The definition of Energy Energy is different from all other concepts in physics in that there is no single definition for it. Instead there are many different kinds of energy. Kinetic Energy Kinetic energy is energy associated with motion. If we uses Newton's laws to compute the work done in accelerating an object, over a certain distance, it turns out that the work is 1 1 W = mv 2− m v 2 net 2 2 2 1 If we define kinetic energy as 1 KE= m v2 2 the result is the work-energy principle The work done in changing the state of motion of an object is equal to the change in the kinetic energy. W net =KE 2−KE 1= KE This relationship is not anything which is not contained in Newton's laws, it is a restatement in terms of energy, and make many problems much easier to solve. 1 Class 15 Potential Energy While Kinetic energy is associated with motion potential energy is associated with position. Whereas kinetic energy has an obvious zero, when the velocity is zero, potential energy is only defined as a change. Potential energy itself has come in different kinds. Gravitational Potential Energy As with kinetic energy we start with the net work done when we lift an object, without any acceleration. If we calculate the work done by an external force in lifting the object shown above we get W ext=F ext d cos0=mg∗ y2− y1 (6.) We can also compute the work done by gravity in the same process. -

Chapter 7 Work and Kinetic Energy

Chapter 7 Work and Kinetic Energy Which one costs energy? Question: (try it) How to throw a baseball to give it large speed? Answer: Apply large force across a large distance! Force exerted through a distance performs mechanical work. 1 Units of Chapter 7 • Work Done by a Constant Force • Kinetic Energy • The Work-Energy Theorem • Work Done by a Variable Force (optional) • Power Read Chapter 8, Potential energy before the next lecture. We will finish Chapter 8 in the next lecture. 2 7-1 Work Done by a Constant Force When the force is parallel to the displacement: Constant force in direction of motion does work W. (7-1) SI unit: newton -meter (N·m) = Joule, J 1 J = 1 N.m 3 If F= 15 N, distance = 2 m , W=30 J 7-1 Work Done by a Constant Force 1J1 Jou le 1 J How much is that? 4 If the force is at an angle to the motion, it does the following work: (7-3) θ is the angle between force and motion direction. Pulling at θ= 20 , F=15N, d=2 m 5 W= Fd cos θ =15*2* cos 20 = 28 J 7-1 Work Done by a Constant Force The work can al so b e writt en as th e d ot product of the force and the displacement: θ is the angle between force and motion directi on. 6 The work done may be positive, zero, or negative, depending on the angle between the force and the motion: Here for F and d we only use their sizes (absolute value). -

Chapter 4 EFFICIENCY of ENERGY CONVERSION

Chapter 4 EFFICIENCY OF ENERGY CONVERSION The National Energy Strategy reflects a National commitment to greater efficiency in every element of energy production and use. Greater energy efficiency can reduce energy costs to consumers, enhance environmental quality, maintain and enhance our standard of living, increase our freedom and energy security, and promote a strong economy. (National Energy Strategy, Executive Summary, 1991/1992) Increased energy efficiency has provided the Nation with significant economic, environmental, and security benefits over the past 20 years. To make further progress toward a sustainable energy future, Administration policy encourages investments in energy efficiency and fuel flexibility in key economic sectors. By focusing on market barriers that inhibit economic investments in efficient technologies and practices, these programs help market forces continually improve the efficiency of our homes, our transportation systems, our offices, and our factories. (Sustainable Energy Strategy, 1995) 54 CHAPTER 4 Our principal criterion for the selection of discussion topics in Chapter 3 was to provide the necessary and sufficient thermodynamics background to allow the reader to grasp the concept of energy efficiency. Here we first want to become familiar with energy conversion devices and heat transfer devices. Examples of the former include automobile engines, hair driers, furnaces and nuclear reactors. Examples of the latter include refrigerators, air conditioners and heat pumps. We then use the knowledge gained in Chapter 3 to show that there are natural (thermodynamic) limitations when energy is converted from one form to another. In Parts II and III of the book, we shall then see that additional technical limitations may exist as well.