LECTURE-3 1. Power Series a Power Series Centered at Z0 ∈ C Is An

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1.1 Constructing the Real Numbers

18.095 Lecture Series in Mathematics IAP 2015 Lecture #1 01/05/2015 What is number theory? The study of numbers of course! But what is a number? • N = f0; 1; 2; 3;:::g can be defined in several ways: { Finite ordinals (0 := fg, n + 1 := n [ fng). { Finite cardinals (isomorphism classes of finite sets). { Strings over a unary alphabet (\", \1", \11", \111", . ). N is a commutative semiring: addition and multiplication satisfy the usual commu- tative/associative/distributive properties with identities 0 and 1 (and 0 annihilates). Totally ordered (as ordinals/cardinals), making it a (positive) ordered semiring. • Z = {±n : n 2 Ng.A commutative ring (commutative semiring, additive inverses). Contains Z>0 = N − f0g closed under +; × with Z = −Z>0 t f0g t Z>0. This makes Z an ordered ring (in fact, an ordered domain). • Q = fa=b : a; 2 Z; b 6= 0g= ∼, where a=b ∼ c=d if ad = bc. A field (commutative ring, multiplicative inverses, 0 6= 1) containing Z = fn=1g. Contains Q>0 = fa=b : a; b 2 Z>0g closed under +; × with Q = −Q>0 t f0g t Q>0. This makes Q an ordered field. • R is the completion of Q, making it a complete ordered field. Each of the algebraic structures N; Z; Q; R is canonical in the following sense: every non-trivial algebraic structure of the same type (ordered semiring, ordered ring, ordered field, complete ordered field) contains a copy of N; Z; Q; R inside it. 1.1 Constructing the real numbers What do we mean by the completion of Q? There are two possibilities: 1. -

Be a Metric Space

2 The University of Sydney show that Z is closed in R. The complement of Z in R is the union of all the Pure Mathematics 3901 open intervals (n, n + 1), where n runs through all of Z, and this is open since every union of open sets is open. So Z is closed. Metric Spaces 2000 Alternatively, let (an) be a Cauchy sequence in Z. Choose an integer N such that d(xn, xm) < 1 for all n ≥ N. Put x = xN . Then for all n ≥ N we have Tutorial 5 |xn − x| = d(xn, xN ) < 1. But xn, x ∈ Z, and since two distinct integers always differ by at least 1 it follows that xn = x. This holds for all n > N. 1. Let X = (X, d) be a metric space. Let (xn) and (yn) be two sequences in X So xn → x as n → ∞ (since for all ε > 0 we have 0 = d(xn, x) < ε for all such that (yn) is a Cauchy sequence and d(xn, yn) → 0 as n → ∞. Prove that n > N). (i)(xn) is a Cauchy sequence in X, and 4. (i) Show that if D is a metric on the set X and f: Y → X is an injective (ii)(xn) converges to a limit x if and only if (yn) also converges to x. function then the formula d(a, b) = D(f(a), f(b)) defines a metric d on Y , and use this to show that d(m, n) = |m−1 − n−1| defines a metric Solution. -

Formal Power Series Rings, Inverse Limits, and I-Adic Completions of Rings

Formal power series rings, inverse limits, and I-adic completions of rings Formal semigroup rings and formal power series rings We next want to explore the notion of a (formal) power series ring in finitely many variables over a ring R, and show that it is Noetherian when R is. But we begin with a definition in much greater generality. Let S be a commutative semigroup (which will have identity 1S = 1) written multi- plicatively. The semigroup ring of S with coefficients in R may be thought of as the free R-module with basis S, with multiplication defined by the rule h k X X 0 0 X X 0 ( risi)( rjsj) = ( rirj)s: i=1 j=1 s2S 0 sisj =s We next want to construct a much larger ring in which infinite sums of multiples of elements of S are allowed. In order to insure that multiplication is well-defined, from now on we assume that S has the following additional property: (#) For all s 2 S, f(s1; s2) 2 S × S : s1s2 = sg is finite. Thus, each element of S has only finitely many factorizations as a product of two k1 kn elements. For example, we may take S to be the set of all monomials fx1 ··· xn : n (k1; : : : ; kn) 2 N g in n variables. For this chocie of S, the usual semigroup ring R[S] may be identified with the polynomial ring R[x1; : : : ; xn] in n indeterminates over R. We next construct a formal semigroup ring denoted R[[S]]: we may think of this ring formally as consisting of all functions from S to R, but we shall indicate elements of the P ring notationally as (possibly infinite) formal sums s2S rss, where the function corre- sponding to this formal sum maps s to rs for all s 2 S. -

Absolute Convergence in Ordered Fields

Absolute Convergence in Ordered Fields Kristine Hampton Abstract This paper reviews Absolute Convergence in Ordered Fields by Clark and Diepeveen [1]. Contents 1 Introduction 2 2 Definition of Terms 2 2.1 Field . 2 2.2 Ordered Field . 3 2.3 The Symbol .......................... 3 2.4 Sequential Completeness and Cauchy Sequences . 3 2.5 New Sequences . 4 3 Summary of Results 4 4 Proof of Main Theorem 5 4.1 Main Theorem . 5 4.2 Proof . 6 5 Further Applications 8 5.1 Infinite Series in Ordered Fields . 8 5.2 Implications for Convergence Tests . 9 5.3 Uniform Convergence in Ordered Fields . 9 5.4 Integral Convergence in Ordered Fields . 9 1 1 Introduction In Absolute Convergence in Ordered Fields [1], the authors attempt to dis- tinguish between convergence and absolute convergence in ordered fields. In particular, Archimedean and non-Archimedean fields (to be defined later) are examined. In each field, the possibilities for absolute convergence with and without convergence are considered. Ultimately, the paper [1] attempts to offer conditions on various fields that guarantee if a series is convergent or not in that field if it is absolutely convergent. The results end up exposing a reliance upon sequential completeness in a field for any statements on the behavior of convergence in relation to absolute convergence to be made, and vice versa. The paper makes a noted attempt to be readable for a variety of mathematic levels, explaining new topics and ideas that might be confusing along the way. To understand the paper, only a basic understanding of series and convergence in R is required, although having a basic understanding of ordered fields would be ideal. -

Infinitesimals Via Cauchy Sequences: Refining the Classical Equivalence

INFINITESIMALS VIA CAUCHY SEQUENCES: REFINING THE CLASSICAL EQUIVALENCE EMANUELE BOTTAZZI AND MIKHAIL G. KATZ Abstract. A refinement of the classic equivalence relation among Cauchy sequences yields a useful infinitesimal-enriched number sys- tem. Such an approach can be seen as formalizing Cauchy’s senti- ment that a null sequence “becomes” an infinitesimal. We signal a little-noticed construction of a system with infinitesimals in a 1910 publication by Giuseppe Peano, reversing his earlier endorsement of Cantor’s belittling of infinitesimals. June 2, 2021 1. Historical background Robinson developed his framework for analysis with infinitesimals in his 1966 book [1]. There have been various attempts either (1) to obtain clarity and uniformity in developing analysis with in- finitesimals by working in a version of set theory with a concept of infinitesimal built in syntactically (see e.g., [2], [3]), or (2) to define nonstandard universes in a simplified way by providing mathematical structures that would not have all the features of a Hewitt–Luxemburg-style ultrapower [4], [5], but nevertheless would suffice for basic application and possibly could be helpful in teaching. The second approach has been carried out, for example, by James Henle arXiv:2106.00229v1 [math.LO] 1 Jun 2021 in his non-nonstandard Analysis [6] (based on Schmieden–Laugwitz [7]; see also [8]), as well as by Terry Tao in his “cheap nonstandard analysis” [9]. These frameworks are based upon the identification of real sequences whenever they are eventually equal.1 A precursor of this approach is found in the work of Giuseppe Peano. In his 1910 paper [10] (see also [11]) he introduced the notion of the end (fine; pl. -

Practice Problems for the Final

Practice problems for the final 1. Show the following using just the definitions (and no theorems). (a) The function ( x2; x ≥ 0 f(x) = 0; x < 0; is differentiable on R, while f 0(x) is not differentiable at 0. Solution: For x > 0 and x < 0, the function is clearly differentiable. We check at x = 0. The difference quotient is f(x) − f(0) f(x) '(x) = = : x x So x2 '(0+) = lim '(x) = lim = 0; x!0+ x!0+ x 0 '(0−) = lim '(x) = lim = 0: x!0− x!0− x 0 Since '(0+) = '(0−), limx!0 '(x) = 0 and hence f is differentiable at 0 with f (0) = 0. So together we get ( 2x; x > 0 f 0(x) = 0; x ≤ 0: f 0(x) is again clearly differentiable for x > 0 and x < 0. To test differentiability at x = 0, we consider the difference quotient f 0(x) − f 0(0) f 0(x) (x) = = : x x Then it is easy to see that (0+) = 2 while (0−) = 0. Since (0+) 6= (0−), limx!0 (x) does not exist, and f 0 is not differentiable at x = 0. (b) The function f(x) = x3 + x is continuous but not uniformly continuous on R. Solution: We show that f is continuous at some x = a. That is given " > 0 we have to find a corresponding δ. jf(x) − f(a)j = jx3 + x − a3 − aj = j(x − a)(x2 + xa + a2) + (x − a)j = jx − ajjx2 + xa + a2 + 1j: Now suppose we pick δ < 1, then jx − aj < δ =) jxj < jaj + 1, and so jx2 + xa + a2 + 1j ≤ jxj2 + jxjjaj + a2 + 1 ≤ 3(jaj + 1)2: To see the final inequality, note that jxjjaj < (jaj + 1)jaj < (jaj + 1)2, and a2 + 1 < (jaj + 1)2. -

Infinitesimals

Infinitesimals: History & Application Joel A. Tropp Plan II Honors Program, WCH 4.104, The University of Texas at Austin, Austin, TX 78712 Abstract. An infinitesimal is a number whose magnitude ex- ceeds zero but somehow fails to exceed any finite, positive num- ber. Although logically problematic, infinitesimals are extremely appealing for investigating continuous phenomena. They were used extensively by mathematicians until the late 19th century, at which point they were purged because they lacked a rigorous founda- tion. In 1960, the logician Abraham Robinson revived them by constructing a number system, the hyperreals, which contains in- finitesimals and infinitely large quantities. This thesis introduces Nonstandard Analysis (NSA), the set of techniques which Robinson invented. It contains a rigorous de- velopment of the hyperreals and shows how they can be used to prove the fundamental theorems of real analysis in a direct, natural way. (Incredibly, a great deal of the presentation echoes the work of Leibniz, which was performed in the 17th century.) NSA has also extended mathematics in directions which exceed the scope of this thesis. These investigations may eventually result in fruitful discoveries. Contents Introduction: Why Infinitesimals? vi Chapter 1. Historical Background 1 1.1. Overview 1 1.2. Origins 1 1.3. Continuity 3 1.4. Eudoxus and Archimedes 5 1.5. Apply when Necessary 7 1.6. Banished 10 1.7. Regained 12 1.8. The Future 13 Chapter 2. Rigorous Infinitesimals 15 2.1. Developing Nonstandard Analysis 15 2.2. Direct Ultrapower Construction of ∗R 17 2.3. Principles of NSA 28 2.4. Working with Hyperreals 32 Chapter 3. -

Uniform Convergence

2018 Spring MATH2060A Mathematical Analysis II 1 Notes 3. UNIFORM CONVERGENCE Uniform convergence is the main theme of this chapter. In Section 1 pointwise and uniform convergence of sequences of functions are discussed and examples are given. In Section 2 the three theorems on exchange of pointwise limits, inte- gration and differentiation which are corner stones for all later development are proven. They are reformulated in the context of infinite series of functions in Section 3. The last two important sections demonstrate the power of uniform convergence. In Sections 4 and 5 we introduce the exponential function, sine and cosine functions based on differential equations. Although various definitions of these elementary functions were given in more elementary courses, here the def- initions are the most rigorous one and all old ones should be abandoned. Once these functions are defined, other elementary functions such as the logarithmic function, power functions, and other trigonometric functions can be defined ac- cordingly. A notable point is at the end of the section, a rigorous definition of the number π is given and showed to be consistent with its geometric meaning. 3.1 Uniform Convergence of Functions Let E be a (non-empty) subset of R and consider a sequence of real-valued func- tions ffng; n ≥ 1 and f defined on E. We call ffng pointwisely converges to f on E if for every x 2 E, the sequence ffn(x)g of real numbers converges to the number f(x). The function f is called the pointwise limit of the sequence. According to the limit of sequence, pointwise convergence means, for each x 2 E, given " > 0, there is some n0(x) such that jfn(x) − f(x)j < " ; 8n ≥ n0(x) : We use the notation n0(x) to emphasis the dependence of n0(x) on " and x. -

Cauchy's Construction of R

CAUCHY’S CONSTRUCTION OF R TODD KEMP CONTENTS 1. Motivation 1 2. Cauchy Sequences 2 3. Equivalence Relations 3 4. Cauchy’s Construction of R 5 References 11 1. MOTIVATION We are used to thinking of real numbers as successive approximations. For example, we write π = 3:14159 ::: to mean that π is a real number which, accurate to 5 decimal places, equals the above string. To be precise, this means that jπ − 3:14159j < 10−5. But this does not tell us what π is. If we want a more accurate approximation, we can calculate one; to 10 decimal places, we have π = 3:1415926536 ::: Continuing, we will develop a sequence of rational approximations to π. One such sequence is 3; 3:1; 3:14; 3:142; 3:1416; 3:14159;::: But this is not the only sequence of rational numbers that approximate π closer and closer (far from it!). For example, here is another (important) one: 22 333 355 104348 1043835 3; ; ; ; ; ::: 7 106 113 33215 332263 (This sequence, which represents the continued fractions approximations to π [you should read about continued fractions for fun!], gives accuracies of 1; 3; 5; 6; 9; 9 decimal digits, as you can readily check.) More’s the point, here is another (somewhat arbitrary) rational approximating sequence to π: 0; 0; 157; −45; −10; 3:14159; 0; 3:14; 3:1415; 3:151592; 3:14159265;::: While here we start with a string of numbers that really have nothing to do with π, the sequence eventually settles down to approximate π closer and closer (this time by an additional 2 decimal places each step). -

1.4 Cauchy Sequence in R

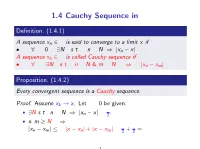

1.4 Cauchy Sequence in R De¯nition. (1.4.1) A sequence xn 2 R is said to converge to a limit x if ² 8² > 0; 9N s:t: n > N ) jxn ¡ xj < ²: A sequence xn 2 R is called Cauchy sequence if ² 8²; 9N s:t: n > N & m > N ) jxn ¡ xmj < ²: Proposition. (1.4.2) Every convergent sequence is a Cauchy sequence. Proof. Assume xk ! x. Let ² > 0 be given. ² ² 9N s:t: n > N ) jxn ¡ xj < 2 . ² n; m ¸ N ) ² ² jxn ¡ xmj · jx ¡ xnj + jx ¡ xmj < 2 + 2 = ²: 1 Theorem. (1.4.3; Bolzano-Weierstrass Property) Every bounded sequence in R has a subsequence that converges to some point in R. Proof. Suppose xn is a bounded sequence in R. 9M such that ¡M · xn · M; n = 1; 2; ¢ ¢ ¢ . Select xn0 = x1. ² Bisect I0 := [¡M; M] into [¡M; 0] and [0; M]. ² At least one of these (either [¡M; 0] or [0; M]) must contain xn for in¯nitely many indices n. ² Call it I1 and select n1 > n0 with xn1 2 I0. ² Continue in this way to get a subsequence xnk such that ² I0 ⊃ I1 ⊃ I2 ⊃ I3 ¢ ¢ ¢ ¡k ² Ik = [ak ; bk ] with jIk j = 2 M. ² Choose n0 < n1 < n2 < ¢ ¢ ¢ with xnk 2 Ik . 9 ² Since ak · ak+1 · M (monotone and bounded), ak ! x. ¡k ² Since xnk 2 Ik and jIk j = 2 M, we have ¡k¡1 jxnk ¡xj < jxnk ¡ak j+jak ¡ xj · 2 M+jak ¡ xj ! 0 as k ! 1: 2 Corollary. (1.4.5; Compactness) Every sequence in the closed interval [a; b] has a subsequence in R that converges to some point in R. -

Open Problems with Factorials

Mathematics Open Problems with Factorials Hermite supervised by Advisor April 22, 2018 Preamble This essay contains the results of a research project on number theory focusing on two open problems that involve the factorial function. This project originated in a mathematics class at school in September 2016 where Stirling's formula was discussed. I was intrigued by the fact that the square root of the quotient nn=n! happened to be very close to the nth Fibonacci number, at least for not too large values of n. This observation triggered my interest for the factorial function. At the same time I had started reading about the ring of p-adic integers (which is an extension of the ordinary integers by allowing base p expansions to become infinite), and learned that many features of ordinary calculus have analogues in the p-adic numbers, for instance the convergence of sequences and infinite series. Then I wondered if there was also a p-adic version of Stirling's formula, providing a non- recursive way of approximating factorials. While pursuing this idea I discovered that p-adic analysis is a rich discipline, relatively recent in the body of mathematics. Although most topics in p-adic analysis are too advanced, I discovered a surpris- ingly unsolved problem by browsing the Internet, namely the series P n! converges in the p-adic metric for all primes p and it is not known whether its sum is rational (i.e., the quotient of two ordinary integers) or irrational. The fact that P n! con- verges can easily be seen in base 10 by observing that when n grows large enough the lowest digits of the partial sums become unchanged since the subsequent terms being added are divisible by increasingly high powers of 10. -

Sequences (2.2.1) Sequence. a Sequence Is a Function Whose

Sequences (2.2.1) Sequence. A sequence is a function whose domain is N. (2.2.3) Convergence of a Sequence. A sequence (an) converges to a real number a if, for every ε > 0, there exists an N ∈ N such that whenever n ≥ N, it follows that |an - a| < ε. (2.2.3B) Convergence of a Sequence, Topological Characterization. A sequence (an) converges to a if, given any ε-neighborhoodε V (a) of a, there exists a point in the sequence after which all of the terms ε are in V (aε) ⇔ every V (a) contains all but a finite number of terms of (an). (2.2.7) Uniqueness of Limits. The limit of a sequence, when it exists, must be unique. (2.2.9) Divergence. A sequence that does not converge is said to diverge. (2.3.1) Bounded. A sequence (xn) is bounded if ∃ M > 0 such that |xn| < M for all n ∈ N. (2.3.2) Every convergent sequence is bounded. (2.3.3) Algebraic Limit Theorem. Let lim an = a and lim bn = b. Then, (i) lim(can) = ca for all c ∈ R; (ii) lim(an + bn) = a + b; (iii) lim(anbn) = ab; (iv) lim(an/bn) = a/b provided b ≠ 0. (2.3.4) Order Limit Theorem. Assume lim an = a and lim bn = b. Then, (i) if an ≥ 0 for all n ∈ N, then a ≥ 0; (ii) if an ≥ bn for every n ∈ N, then a ≥ b; (iii) If there exists c ∈ R for which c ≤ an for all n ∈ N, then c ≤ a.