Infinitesimals Via Cauchy Sequences: Refining the Classical Equivalence

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Richard Dedekind English Version

RICHARD DEDEKIND (October 6, 1831 – February 12, 1916) by HEINZ KLAUS STRICK, Germany The biography of JULIUS WILHELM RICHARD DEDEKIND begins and ends in Braunschweig (Brunswick): The fourth child of a professor of law at the Collegium Carolinum, he attended the Martino-Katherineum, a traditional gymnasium (secondary school) in the city. At the age of 16, the boy, who was also a highly gifted musician, transferred to the Collegium Carolinum, an educational institution that would pave the way for him to enter the university after high school. There he prepared for future studies in mathematics. In 1850, he went to the University at Göttingen, where he enthusiastically attended lectures on experimental physics by WILHELM WEBER, and where he met CARL FRIEDRICH GAUSS when he attended a lecture given by the great mathematician on the method of least squares. GAUSS was nearing the end of his life and at the time was involved primarily in activities related to astronomy. After only four semesters, DEDEKIND had completed a doctoral dissertation on the theory of Eulerian integrals. He was GAUSS’s last doctoral student. (drawings © Andreas Strick) He then worked on his habilitation thesis, in parallel with BERNHARD RIEMANN, who had also received his doctoral degree under GAUSS’s direction not long before. In 1854, after obtaining the venia legendi (official permission allowing those completing their habilitation to lecture), he gave lectures on probability theory and geometry. Since the beginning of his stay in Göttingen, DEDEKIND had observed that the mathematics faculty, who at the time were mostly preparing students to become secondary-school teachers, had lost contact with current developments in mathematics; this in contrast to the University of Berlin, at which PETER GUSTAV LEJEUNE DIRICHLET taught. -

1.1 Constructing the Real Numbers

18.095 Lecture Series in Mathematics IAP 2015 Lecture #1 01/05/2015 What is number theory? The study of numbers of course! But what is a number? • N = f0; 1; 2; 3;:::g can be defined in several ways: { Finite ordinals (0 := fg, n + 1 := n [ fng). { Finite cardinals (isomorphism classes of finite sets). { Strings over a unary alphabet (\", \1", \11", \111", . ). N is a commutative semiring: addition and multiplication satisfy the usual commu- tative/associative/distributive properties with identities 0 and 1 (and 0 annihilates). Totally ordered (as ordinals/cardinals), making it a (positive) ordered semiring. • Z = {±n : n 2 Ng.A commutative ring (commutative semiring, additive inverses). Contains Z>0 = N − f0g closed under +; × with Z = −Z>0 t f0g t Z>0. This makes Z an ordered ring (in fact, an ordered domain). • Q = fa=b : a; 2 Z; b 6= 0g= ∼, where a=b ∼ c=d if ad = bc. A field (commutative ring, multiplicative inverses, 0 6= 1) containing Z = fn=1g. Contains Q>0 = fa=b : a; b 2 Z>0g closed under +; × with Q = −Q>0 t f0g t Q>0. This makes Q an ordered field. • R is the completion of Q, making it a complete ordered field. Each of the algebraic structures N; Z; Q; R is canonical in the following sense: every non-trivial algebraic structure of the same type (ordered semiring, ordered ring, ordered field, complete ordered field) contains a copy of N; Z; Q; R inside it. 1.1 Constructing the real numbers What do we mean by the completion of Q? There are two possibilities: 1. -

Be a Metric Space

2 The University of Sydney show that Z is closed in R. The complement of Z in R is the union of all the Pure Mathematics 3901 open intervals (n, n + 1), where n runs through all of Z, and this is open since every union of open sets is open. So Z is closed. Metric Spaces 2000 Alternatively, let (an) be a Cauchy sequence in Z. Choose an integer N such that d(xn, xm) < 1 for all n ≥ N. Put x = xN . Then for all n ≥ N we have Tutorial 5 |xn − x| = d(xn, xN ) < 1. But xn, x ∈ Z, and since two distinct integers always differ by at least 1 it follows that xn = x. This holds for all n > N. 1. Let X = (X, d) be a metric space. Let (xn) and (yn) be two sequences in X So xn → x as n → ∞ (since for all ε > 0 we have 0 = d(xn, x) < ε for all such that (yn) is a Cauchy sequence and d(xn, yn) → 0 as n → ∞. Prove that n > N). (i)(xn) is a Cauchy sequence in X, and 4. (i) Show that if D is a metric on the set X and f: Y → X is an injective (ii)(xn) converges to a limit x if and only if (yn) also converges to x. function then the formula d(a, b) = D(f(a), f(b)) defines a metric d on Y , and use this to show that d(m, n) = |m−1 − n−1| defines a metric Solution. -

Formal Power Series Rings, Inverse Limits, and I-Adic Completions of Rings

Formal power series rings, inverse limits, and I-adic completions of rings Formal semigroup rings and formal power series rings We next want to explore the notion of a (formal) power series ring in finitely many variables over a ring R, and show that it is Noetherian when R is. But we begin with a definition in much greater generality. Let S be a commutative semigroup (which will have identity 1S = 1) written multi- plicatively. The semigroup ring of S with coefficients in R may be thought of as the free R-module with basis S, with multiplication defined by the rule h k X X 0 0 X X 0 ( risi)( rjsj) = ( rirj)s: i=1 j=1 s2S 0 sisj =s We next want to construct a much larger ring in which infinite sums of multiples of elements of S are allowed. In order to insure that multiplication is well-defined, from now on we assume that S has the following additional property: (#) For all s 2 S, f(s1; s2) 2 S × S : s1s2 = sg is finite. Thus, each element of S has only finitely many factorizations as a product of two k1 kn elements. For example, we may take S to be the set of all monomials fx1 ··· xn : n (k1; : : : ; kn) 2 N g in n variables. For this chocie of S, the usual semigroup ring R[S] may be identified with the polynomial ring R[x1; : : : ; xn] in n indeterminates over R. We next construct a formal semigroup ring denoted R[[S]]: we may think of this ring formally as consisting of all functions from S to R, but we shall indicate elements of the P ring notationally as (possibly infinite) formal sums s2S rss, where the function corre- sponding to this formal sum maps s to rs for all s 2 S. -

Absolute Convergence in Ordered Fields

Absolute Convergence in Ordered Fields Kristine Hampton Abstract This paper reviews Absolute Convergence in Ordered Fields by Clark and Diepeveen [1]. Contents 1 Introduction 2 2 Definition of Terms 2 2.1 Field . 2 2.2 Ordered Field . 3 2.3 The Symbol .......................... 3 2.4 Sequential Completeness and Cauchy Sequences . 3 2.5 New Sequences . 4 3 Summary of Results 4 4 Proof of Main Theorem 5 4.1 Main Theorem . 5 4.2 Proof . 6 5 Further Applications 8 5.1 Infinite Series in Ordered Fields . 8 5.2 Implications for Convergence Tests . 9 5.3 Uniform Convergence in Ordered Fields . 9 5.4 Integral Convergence in Ordered Fields . 9 1 1 Introduction In Absolute Convergence in Ordered Fields [1], the authors attempt to dis- tinguish between convergence and absolute convergence in ordered fields. In particular, Archimedean and non-Archimedean fields (to be defined later) are examined. In each field, the possibilities for absolute convergence with and without convergence are considered. Ultimately, the paper [1] attempts to offer conditions on various fields that guarantee if a series is convergent or not in that field if it is absolutely convergent. The results end up exposing a reliance upon sequential completeness in a field for any statements on the behavior of convergence in relation to absolute convergence to be made, and vice versa. The paper makes a noted attempt to be readable for a variety of mathematic levels, explaining new topics and ideas that might be confusing along the way. To understand the paper, only a basic understanding of series and convergence in R is required, although having a basic understanding of ordered fields would be ideal. -

1 CS Peirce's Classification of Dyadic Relations: Exploring The

C.S. Peirce’s Classification of Dyadic Relations: Exploring the Relevance for Logic and Mathematics Jeffrey Downard1 In “The Logic of Mathematics; an Attempt to Develop my Categories from Within” [CP 1.417-520] Charles S. Peirce develops a scheme for classifying different kinds of monadic, dyadic and triadic relations. His account of these different classes of relations figures prominently in many parts of his philosophical system, including the phenomenological account of the categories of experience, the semiotic account of the relations between signs, objects and the metaphysical explanations of the nature of such things as chance, brute existence, law-governed regularities and the making and breaking of habits. Our aim in this essay is to reconstruct and examine central features of the classificatory system that he develops in this essay. Given the complexity of the system, we will focus our attention in this essay mainly on different classes of degenerate and genuine dyadic relations, and we will take up the discussion of triadic relations in a companion piece. One of our reasons for wanting to explore Peirce’s philosophical account of relations is to better understand how it might have informed the later development of relations as 1 Associate Professor, Department of Philosophy, Northern Arizona University. 2 In what follows, I will refer to Peirce’s essay “The Logic of Mathematics; An Attempt to Develop my Categories from Within” using the abbreviated title “The Logic of Mathematics.” 3 One reason to retain all of the parts of the figures—including the diamonds that represent the saturated bonds—is that it makes it possible to study more closely the combinatorial possibilities of the system. -

Peano 441 Peano

PEANO PEANO On his life and work, see M . Berthelot, "Necrologie," his position at the military academy but retained his in Bulletin . Societe chindque de France, A5 (1863), 226- professorship at the university until his death in 1932, 227 ; J. R. Partington, A History of Chemistry, IV (London, having transferred in 1931 to the chair of complemen- 1964), 584-585 ; and F. Szabadvary, History of Analytical tary mathematics. He was elected to a number of Chemistry (Oxford, 1966), 251 . scientific societies, among them the Academy of F . SZABADVARY Sciences of Turin, in which he played a very active role . He was also a knight of the Order of the Crown of Italy and of the Order of Saint Maurizio and PEANO, GIUSEPPE (b . Spinetta, near Cuneo, Italy, Saint Lazzaro. Although lie was not active politically, 27 August 1858 ; d. Turin, Italy, 20 April 1932), his views tended toward socialism ; and lie once invited mathematics, logic . a group of striking textile workers to a party at his Giuseppe Peano was the second of the five children home. During World War I he advocated a closer of Bartolomeo Peano and Rosa Cavallo . His brother federation of the allied countries, to better prosecute Michele was seven years older . There were two the war and, after the peace, to form the nucleus of a younger brothers, Francesco and Bartolomeo, and a world federation . Peano was a nonpracticing Roman sister, Rosa . Peano's first home was the farm Tetto Catholic . Galant, near the village of Spinetta, three miles from Peano's father died in 1888 ; his mother, in 1910. -

Practice Problems for the Final

Practice problems for the final 1. Show the following using just the definitions (and no theorems). (a) The function ( x2; x ≥ 0 f(x) = 0; x < 0; is differentiable on R, while f 0(x) is not differentiable at 0. Solution: For x > 0 and x < 0, the function is clearly differentiable. We check at x = 0. The difference quotient is f(x) − f(0) f(x) '(x) = = : x x So x2 '(0+) = lim '(x) = lim = 0; x!0+ x!0+ x 0 '(0−) = lim '(x) = lim = 0: x!0− x!0− x 0 Since '(0+) = '(0−), limx!0 '(x) = 0 and hence f is differentiable at 0 with f (0) = 0. So together we get ( 2x; x > 0 f 0(x) = 0; x ≤ 0: f 0(x) is again clearly differentiable for x > 0 and x < 0. To test differentiability at x = 0, we consider the difference quotient f 0(x) − f 0(0) f 0(x) (x) = = : x x Then it is easy to see that (0+) = 2 while (0−) = 0. Since (0+) 6= (0−), limx!0 (x) does not exist, and f 0 is not differentiable at x = 0. (b) The function f(x) = x3 + x is continuous but not uniformly continuous on R. Solution: We show that f is continuous at some x = a. That is given " > 0 we have to find a corresponding δ. jf(x) − f(a)j = jx3 + x − a3 − aj = j(x − a)(x2 + xa + a2) + (x − a)j = jx − ajjx2 + xa + a2 + 1j: Now suppose we pick δ < 1, then jx − aj < δ =) jxj < jaj + 1, and so jx2 + xa + a2 + 1j ≤ jxj2 + jxjjaj + a2 + 1 ≤ 3(jaj + 1)2: To see the final inequality, note that jxjjaj < (jaj + 1)jaj < (jaj + 1)2, and a2 + 1 < (jaj + 1)2. -

Infinitesimals

Infinitesimals: History & Application Joel A. Tropp Plan II Honors Program, WCH 4.104, The University of Texas at Austin, Austin, TX 78712 Abstract. An infinitesimal is a number whose magnitude ex- ceeds zero but somehow fails to exceed any finite, positive num- ber. Although logically problematic, infinitesimals are extremely appealing for investigating continuous phenomena. They were used extensively by mathematicians until the late 19th century, at which point they were purged because they lacked a rigorous founda- tion. In 1960, the logician Abraham Robinson revived them by constructing a number system, the hyperreals, which contains in- finitesimals and infinitely large quantities. This thesis introduces Nonstandard Analysis (NSA), the set of techniques which Robinson invented. It contains a rigorous de- velopment of the hyperreals and shows how they can be used to prove the fundamental theorems of real analysis in a direct, natural way. (Incredibly, a great deal of the presentation echoes the work of Leibniz, which was performed in the 17th century.) NSA has also extended mathematics in directions which exceed the scope of this thesis. These investigations may eventually result in fruitful discoveries. Contents Introduction: Why Infinitesimals? vi Chapter 1. Historical Background 1 1.1. Overview 1 1.2. Origins 1 1.3. Continuity 3 1.4. Eudoxus and Archimedes 5 1.5. Apply when Necessary 7 1.6. Banished 10 1.7. Regained 12 1.8. The Future 13 Chapter 2. Rigorous Infinitesimals 15 2.1. Developing Nonstandard Analysis 15 2.2. Direct Ultrapower Construction of ∗R 17 2.3. Principles of NSA 28 2.4. Working with Hyperreals 32 Chapter 3. -

Uniform Convergence

2018 Spring MATH2060A Mathematical Analysis II 1 Notes 3. UNIFORM CONVERGENCE Uniform convergence is the main theme of this chapter. In Section 1 pointwise and uniform convergence of sequences of functions are discussed and examples are given. In Section 2 the three theorems on exchange of pointwise limits, inte- gration and differentiation which are corner stones for all later development are proven. They are reformulated in the context of infinite series of functions in Section 3. The last two important sections demonstrate the power of uniform convergence. In Sections 4 and 5 we introduce the exponential function, sine and cosine functions based on differential equations. Although various definitions of these elementary functions were given in more elementary courses, here the def- initions are the most rigorous one and all old ones should be abandoned. Once these functions are defined, other elementary functions such as the logarithmic function, power functions, and other trigonometric functions can be defined ac- cordingly. A notable point is at the end of the section, a rigorous definition of the number π is given and showed to be consistent with its geometric meaning. 3.1 Uniform Convergence of Functions Let E be a (non-empty) subset of R and consider a sequence of real-valued func- tions ffng; n ≥ 1 and f defined on E. We call ffng pointwisely converges to f on E if for every x 2 E, the sequence ffn(x)g of real numbers converges to the number f(x). The function f is called the pointwise limit of the sequence. According to the limit of sequence, pointwise convergence means, for each x 2 E, given " > 0, there is some n0(x) such that jfn(x) − f(x)j < " ; 8n ≥ n0(x) : We use the notation n0(x) to emphasis the dependence of n0(x) on " and x. -

Cauchy's Construction of R

CAUCHY’S CONSTRUCTION OF R TODD KEMP CONTENTS 1. Motivation 1 2. Cauchy Sequences 2 3. Equivalence Relations 3 4. Cauchy’s Construction of R 5 References 11 1. MOTIVATION We are used to thinking of real numbers as successive approximations. For example, we write π = 3:14159 ::: to mean that π is a real number which, accurate to 5 decimal places, equals the above string. To be precise, this means that jπ − 3:14159j < 10−5. But this does not tell us what π is. If we want a more accurate approximation, we can calculate one; to 10 decimal places, we have π = 3:1415926536 ::: Continuing, we will develop a sequence of rational approximations to π. One such sequence is 3; 3:1; 3:14; 3:142; 3:1416; 3:14159;::: But this is not the only sequence of rational numbers that approximate π closer and closer (far from it!). For example, here is another (important) one: 22 333 355 104348 1043835 3; ; ; ; ; ::: 7 106 113 33215 332263 (This sequence, which represents the continued fractions approximations to π [you should read about continued fractions for fun!], gives accuracies of 1; 3; 5; 6; 9; 9 decimal digits, as you can readily check.) More’s the point, here is another (somewhat arbitrary) rational approximating sequence to π: 0; 0; 157; −45; −10; 3:14159; 0; 3:14; 3:1415; 3:151592; 3:14159265;::: While here we start with a string of numbers that really have nothing to do with π, the sequence eventually settles down to approximate π closer and closer (this time by an additional 2 decimal places each step). -

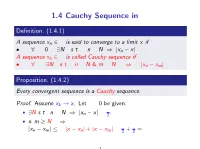

1.4 Cauchy Sequence in R

1.4 Cauchy Sequence in R De¯nition. (1.4.1) A sequence xn 2 R is said to converge to a limit x if ² 8² > 0; 9N s:t: n > N ) jxn ¡ xj < ²: A sequence xn 2 R is called Cauchy sequence if ² 8²; 9N s:t: n > N & m > N ) jxn ¡ xmj < ²: Proposition. (1.4.2) Every convergent sequence is a Cauchy sequence. Proof. Assume xk ! x. Let ² > 0 be given. ² ² 9N s:t: n > N ) jxn ¡ xj < 2 . ² n; m ¸ N ) ² ² jxn ¡ xmj · jx ¡ xnj + jx ¡ xmj < 2 + 2 = ²: 1 Theorem. (1.4.3; Bolzano-Weierstrass Property) Every bounded sequence in R has a subsequence that converges to some point in R. Proof. Suppose xn is a bounded sequence in R. 9M such that ¡M · xn · M; n = 1; 2; ¢ ¢ ¢ . Select xn0 = x1. ² Bisect I0 := [¡M; M] into [¡M; 0] and [0; M]. ² At least one of these (either [¡M; 0] or [0; M]) must contain xn for in¯nitely many indices n. ² Call it I1 and select n1 > n0 with xn1 2 I0. ² Continue in this way to get a subsequence xnk such that ² I0 ⊃ I1 ⊃ I2 ⊃ I3 ¢ ¢ ¢ ¡k ² Ik = [ak ; bk ] with jIk j = 2 M. ² Choose n0 < n1 < n2 < ¢ ¢ ¢ with xnk 2 Ik . 9 ² Since ak · ak+1 · M (monotone and bounded), ak ! x. ¡k ² Since xnk 2 Ik and jIk j = 2 M, we have ¡k¡1 jxnk ¡xj < jxnk ¡ak j+jak ¡ xj · 2 M+jak ¡ xj ! 0 as k ! 1: 2 Corollary. (1.4.5; Compactness) Every sequence in the closed interval [a; b] has a subsequence in R that converges to some point in R.